Evaluation of Acute Pancreatitis in the Older Patient

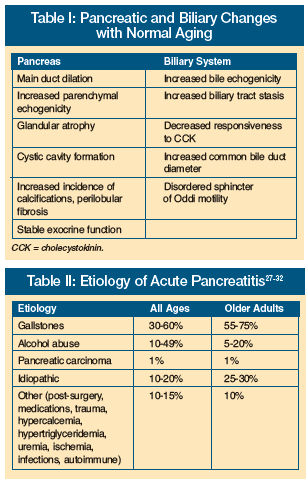

As many as 30% of acute pancreatitis occurs in patients older than age 65 years.1 A minority are severe, with local complications and organ failure with or without morphologic changes on computed tomography (CT) scan indicative of pancreatic necrosis.2 Severe acute pancreatitis is associated with an 8-10% mortality; in older patients, the mortality is as high as 20-25%.3 A greater propensity to fulminant disease in old age has been attributed to diminished organ function reserve, comorbid illness, diminishing ability to tolerate fluid shifts, and susceptibility to ischemia and infection.4 Age-associated changes in the pancreas and biliary system are listed in Table I. We review the etiology, evaluation, and management of pancreatic inflammation in the elderly to alert clinicians to the unique features of acute pancreatitis in this age group.

Age-Related Structural Changes in the Pancreas

Diagnosis may be complicated by changes in organ structure with normal aging. Pancreatic ducts have been reported to dilate with age at an average of 8% per decade after age 40.5 Hastier and coworkers6 reported that only 31.4% (33 of 105) of patients older than age 70 years without pancreatic pathology had duct diameters within defined normal limits. The main pancreatic duct in some older patients may reach 1 cm in diameter without evidence of obstruction or clinical chronic pancreatitis. The dilation is generally insidious and uniform throughout the pancreas, unlike the subacute, irregular dilation commonly seen in chronic pancreatitis. In some older patients, ductal ectasia may be cystic, mimicking a pancreatic pseudocyst or cystic neoplasm. Ductal or parenchymal calculi may form, unassociated with chronic pancreatitis.7 In a Japanese review of 130,000 abdominal ultrasound examinations of asymptomatic  patients, 84% of main pancreatic duct dilatations, 87% of cystic areas, and half of all calcifications were considered to be purely age-related, unassociated with any pathology.8

patients, 84% of main pancreatic duct dilatations, 87% of cystic areas, and half of all calcifications were considered to be purely age-related, unassociated with any pathology.8

In an autopsy study of pancreatograms in 60 older patients without clinical history or histologic evidence of pancreatic disease, false-positive duct changes consistent with those of chronic pancreatitis were found in 81% of cases.9 Caution must be exercised in interpretation of pancreatograms because normal aging changes may simulate those of chronic pancreatitis or pancreatic carcinoma (Table I). Increased diameter of the common bile duct of up to 10 mm has also been reported in aging, with normal levels post-cholecystectomy as high as 14 mm.10 On a gross level, the aged pancreas also atrophies.5 An atrophic gland, terminating abruptly on endoscopic or magnetic resonance pancreatography, may be misdiagnosed as an obstruction at that point.

Etiology

Pancreatitis in older patients, as compared with a younger cohort, is much more likely to be due to gallstone pancreatitis (Table II). In the elderly patient, the etiology of as many as 75% of episodes of acute pancreatitis is biliary disease. Contributing factors may include increased lithogenicity of bile, increased likelihood of infected bile, and increased propensity for gallstone formation.11

Although excessive alcohol use is a common cause of pancreatic inflammation in younger patients, only 5% of episodes in the older patient are due to alcohol abuse. Alcohol abuse is, however, the most common cause of chronic pancreatitis, which may present as an episode of acute pancreatitis unaccompanied by exocrine or endocrine insufficiency. Because covert alcohol use is common, routine evaluation of every older patient should include age-adjusted alcohol screening questions.12

Metabolic and medication-induced etiologies must also be assessed. Older women taking hormone replacement therapy are at risk for hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis, thought to be due to free fatty acid release from serum triglycerides by the action of pancreatic lipase. Pancreatic inflammation usually does not occur until the serum triglyceride level is greater than 1000 mg/dL. Marked elevation may also be associated with hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus. Hypercalcemia may also rarely cause pancreatitis, possibly by calcium-induced activation of trypsinogen to its active form, trypsin. The diagnosis of medication-induced pancreatitis is challenging, particularly in the older adult taking many medications. As many as 100 culprit medications commonly used by older adults have been potentially implicated. A thorough history from the patient and/or caregiver is essential.

Although a rare cause of pancreatitis, pancreatic adenocarcinoma also must be considered. Pancreatic cancer, a ductal adenocarcinoma, obstructs the main pancreatic duct, producing ductal hypertension with subsequent leakage of enzymes into the parenchyma. In malignancy-associated pancreatitis, the focal mass effect of a tumor may be obscured on a CT scan by diffuse inflammatory changes.13

Infections are uncommon etiologies of pancreatitis, and include viruses (mumps, Coxsackie, HIV, herpes simplex, hepatitis), bacteria (mycobacteria, mycoplasma, brucellosis, salmonella), fungi (aspergillus, candida), and parasites. Older patients should be questioned about foreign travel since exotic infections may occur. AIDS is associated with an increased risk of pancreatitis due to medication side effects and increased susceptibility to infection. Hyperamylasemia or hyperlipasemia, unassociated with evidence of pancreatic inflammation, has been described in as many as 8-10% of asymptomatic patients with AIDS.14 An increased incidence and severity of pancreatitis exists in patients with shock or hypotension. Acute pancreatitis is more severe with inadequate fluid replacement, medication-induced hypotension, or pre-existing mesenteric ischemia, all of which are common in the elderly.

Despite a complete evaluation, 10-30% of patients have unexplained or idiopathic disease. Genetic mutation has been implicated in some cases. In one study of 18 patients with a cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) mutation causing pancreatitis, one subject had an age of onset of 64 years and another of 75 years.15 Such gene mutations may play a facilitating role in causing pancreatic inflammation in presumed alcoholic pancreatitis. An unknown percentage of undiagnosed cases may represent occult biliary disease (including sludge or microlithiasis), unreported alcohol abuse, or uninvestigated genetic or autoimmune etiologies.

Clinical Presentation

Abdominal pain, the cardinal symptom of acute pancreatitis, is variable, ranging from mild epigastric discomfort to diffuse, unremitting, excruciating pain. Colicky or intermittent pain suggests another diagnosis. Older patients may have mild or no pain, perhaps due to neuropathy (eg, diabetes), greater pain tolerance, or increase in fibrosis of the perineurium due to normal aging.16 One report of nine elderly patients with acute interstitial pancreatitis, discovered only at autopsy, noted few clinical clues except for rapidly developing shock.17 Transient changes in exocrine and endocrine function occurring during acute pancreatitis make assessment of glucose tolerance and steatorrhea inaccurate until inflammation subsides. Physical examination findings help to determine severity. Low-grade fever and tachycardia are common. Fulminant episodes may be associated with confusion, delirium, shock, hypotension, hypothermia, or tachypnea. Scleral icterus suggests choledocholithiasis, underlying chronic liver disease, or contiguous pancreatic inflammation encasing the distal, intra-pancreatic portion of the common bile duct. Abdominal tenderness is variable. The clinician must be vigilant for signs of organ failure.18

Diagnostic Tests

In acute pancreatitis, digestive enzymes leak out of acinar cells into the interstitium, and then to the bloodstream. Elevation of serum amylase and lipase are nonspecific, however, occurring in a wide variety of nonpancreatic disorders with overlapping clinical features (Table III).19 Modest elevations (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal) have occasionally been reported with normal aging, a finding not yet confirmed in a large cohort.20 Pancreatitis may be clinically indistinguishable from other intra-abdominal conditions with similar features and enzyme elevations, including mesenteric ischemia with leakage of luminal amylase and lipase from the gut, acute biliary disease, and perforated ulcer. Increased serum amylase and lipase levels are seen in renal insufficiency (as high as 3-4 times the upper limit of normal), metabolic acidosis, hypotension, hypoperfusion, and trauma.21,22 Despite the lack of specificity, serum elevations of amylase and lipase form the basis of the diagnosis of pancreatitis in the appropriate clinical context. The degree of enzymatic elevation does not correlate with severity of disease; patients with only modest (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal) elevations of serum enzymes may have or develop severe acute pancreatitis.23

In acute pancreatitis, digestive enzymes leak out of acinar cells into the interstitium, and then to the bloodstream. Elevation of serum amylase and lipase are nonspecific, however, occurring in a wide variety of nonpancreatic disorders with overlapping clinical features (Table III).19 Modest elevations (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal) have occasionally been reported with normal aging, a finding not yet confirmed in a large cohort.20 Pancreatitis may be clinically indistinguishable from other intra-abdominal conditions with similar features and enzyme elevations, including mesenteric ischemia with leakage of luminal amylase and lipase from the gut, acute biliary disease, and perforated ulcer. Increased serum amylase and lipase levels are seen in renal insufficiency (as high as 3-4 times the upper limit of normal), metabolic acidosis, hypotension, hypoperfusion, and trauma.21,22 Despite the lack of specificity, serum elevations of amylase and lipase form the basis of the diagnosis of pancreatitis in the appropriate clinical context. The degree of enzymatic elevation does not correlate with severity of disease; patients with only modest (less than 2 times the upper limit of normal) elevations of serum enzymes may have or develop severe acute pancreatitis.23

Normal serum amylase and lipase levels do not exclude acute pancreatitis. In one consecutive series, normal serum amylase was documented in 67 of 352 (19%) of contrast–enhanced CT-proven cases of acute pancreatitis.24 Enzyme elevations are transient, returning to normal commonly within two or three days after the onset of an attack. Misdiagnosis may occur if testing is done after enzyme levels have normalized. As many as one-third of patients with alcoholic pancreatitis will have normal serum enzymes during an acute exacerbation because the pancreas is no longer able to produce amylase or lipase.25 Fulminant pancreatitis, more common in the older patient, may be associated with extensive destruction of the gland, rendering it unable to secrete enzymes.

Imaging Studies

Ultrasonography is generally indicated in the elderly to evaluate for gallstones. However, ultrasonogaphy is insensitive for evaluation of common bile duct stones or pancreatic inflammation. Any acute abdominal inflammatory disorder may be associated with ileus or excessive bowel gas, potentially obscuring both the pancreas and biliary tract, thus limiting visualization by sonography. In the older adult, the high incidence of gallstone pancreatitis and the poor sensitivity of CT scan for biliary stones make ultrasonography useful after clinical resolution, or as the initial imaging study in mild, uncomplicated cases.

Intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal and pelvic CT scan is the gold standard for the noninvasive diagnosis of acute pancreatitis but is not performed in every case. CT is indicated for the following: (1) to confirm the clinical impression in severe disease; (2) to exclude other serious abdominal disorders; (3) when the diagnosis is uncertain; (4) to evaluate for complications or pancreatic necrosis in fulminant episodes; (5) when no improvement occurs in the first 48 hours; or (6) to investigate acute deterioration.26 The declining creatinine clearance with age and marginal renal reserve in older adults must always be assessed because of the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) must be considered when cholangitis is suspected clinically, or with biochemical evidence of common bile duct obstruction, bile duct dilatation, or choledocholithiasis on imaging studies. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is a newer, noninvasive method to image pancreatic and biliary ducts.27 Accuracy of MRCP is similar to ERCP, but the former does not have the therapeutic potential of ERCP to remove common bile duct stones in patients with pancreatitis or biliary sepsis. MRCP, the less invasive test, is preferred in debilitated patients and in those with a low clinical probability of common bile duct stones in whom ductal visualization is clinically indicated. Patients with high likelihood of stones should be considered for ERCP. The contribution of normal aging changes of the pancreas and biliary system, including common bile duct dilatation, should be assessed when interpreting diagnostic imaging findings.

Assessment of Severity

Most cases of acute pancreatitis are mild and self-limited. Ten to 20% are severe, generally associated with multi-organ failure with or without necrotizing pancreatitis. Approximately half of all deaths occur in the first 10 days, characterized by the systemic inflammatory response syndrome and persistent organ failure.28 Identification of adverse prognostic factors on admission may lead to early contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan, prophylactic antibiotics to prevent secondary pancreatic infection, or endoscopic sphincterotomy for predicted severe gallstone-induced pancreatitis. Serum levels of amylase and lipase, although diagnostically useful, have no predictive role in assessing clinical severity.

Increased age predicting a severe episode is a major criterion in two widely recognized clinical scoring systems of pancreatitis severity, the Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE II) and Ranson’s criteria. Recent data support advanced age as an independent predictor of poor prognosis.29 Hypotension, shock, renal dysfunction, and respiratory failure correlate with necrotizing pancreatitis. Unfortunately, these features usually are present infrequently early in the course of an episode destined to be severe. Fan and coworkers30 reported a 21% mortality in a series of patients greater than age 75 years. Their data suggested that comorbid illness in older adults, rather than more severe inflammatory disease, was responsible for increased mortality. Malnutrition on admission correlates with adverse outcome during hospitalization and post-discharge.31 Hemoconcentration at presentation (hematocrit > 47%) with failure to normalize within the first 24 hours may reflect severe inflammation and inadequate fluid resuscitation, with a relative decrease in intravascular volume. The result is decreased pancreatic perfusion, ischemia, and increased risk of necrosis.32

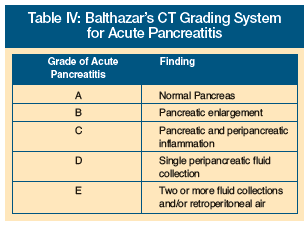

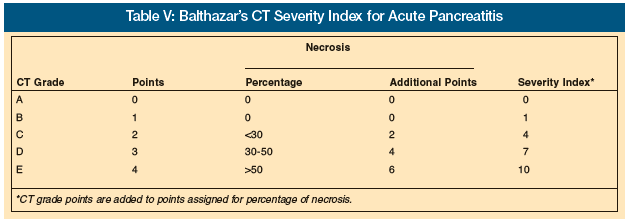

Intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scan assesses severity by demonstrating nonenhancing necrotic tissue, pancreatic edema, and fluid collections. Balthazar’s CT grading system (Table IV), using contrast-enhanced CT, has a high sensitivity and specificity for staging; its use in risk stratification of older patients is recommended.26 CT is the current gold standard to differentiate interstitial from necrotizing pancreatitis by demonstrating necrotic tissue that does not enhance with contrast injection. Patients with pancreatitis graded A to E are assigned from 0-4 points based on increasing CT abnormalities (Table V). Episodes with grade D or E have a reported mortality rate of 14%, while those with A, B, or C have a mortality rate as low as 4%. In a further modification, the percentage of necrotic pancreatic parenchyma is assigned an added numerical value, with 2 points for necrosis of up to 30% of the pancreas, 4 points for necrosis of 30-50%, and 6 points for necrosis of greater than 50%. Balthazar and colleagues26 have reported that a score of 7-10 points is associated with a morbidity of 92% and mortality of 17%. As an example of the CT severity index, a patient with grade D pancreatitis would be assigned 3 points. If this individual had CT-documented necrosis of 30-50% of the pancreatic parenchyma, an additional 4 points would be assessed, yielding a total score of 7. Clinicians should be advised, however, that a normal CT scan in an elderly patient with suspected pancreatitis may also reflect a nonpancreatic cause for pain, such as mesenteric ischemia with leakage of luminal amylase or lipase into serum.

Intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scan assesses severity by demonstrating nonenhancing necrotic tissue, pancreatic edema, and fluid collections. Balthazar’s CT grading system (Table IV), using contrast-enhanced CT, has a high sensitivity and specificity for staging; its use in risk stratification of older patients is recommended.26 CT is the current gold standard to differentiate interstitial from necrotizing pancreatitis by demonstrating necrotic tissue that does not enhance with contrast injection. Patients with pancreatitis graded A to E are assigned from 0-4 points based on increasing CT abnormalities (Table V). Episodes with grade D or E have a reported mortality rate of 14%, while those with A, B, or C have a mortality rate as low as 4%. In a further modification, the percentage of necrotic pancreatic parenchyma is assigned an added numerical value, with 2 points for necrosis of up to 30% of the pancreas, 4 points for necrosis of 30-50%, and 6 points for necrosis of greater than 50%. Balthazar and colleagues26 have reported that a score of 7-10 points is associated with a morbidity of 92% and mortality of 17%. As an example of the CT severity index, a patient with grade D pancreatitis would be assigned 3 points. If this individual had CT-documented necrosis of 30-50% of the pancreatic parenchyma, an additional 4 points would be assessed, yielding a total score of 7. Clinicians should be advised, however, that a normal CT scan in an elderly patient with suspected pancreatitis may also reflect a nonpancreatic cause for pain, such as mesenteric ischemia with leakage of luminal amylase or lipase into serum.

Management

Treatment plans in the older patient should begin with assessment of the patient’s goals of care, including do-not-resuscitate orders, preservation of physical function, and proper informed consent. Nutrition concerns are especially important in acute pancreatitis, a hypermetabolic disorder characterized by increased energy expenditure, proteolysis, gluconeogenesis, and insulin resistance.33 The majority of patients require supportive care with hospitalization for intravenous fluids and nothing-by-mouth status. Most patients with predicted mild disease may begin re-feeding as clinical and laboratory markers of inflammation subside. Feeding may not be tolerated because of postprandial pain, nausea, or vomiting. Early pain relief is crucial to prevent unnecessary suffering. Although elderly patients may be less able to tolerate fluid shifts, failure to provide adequate hydration may increase ischemia-related pancreatic injury. Clinicians must be aware, however, that in the elderly, oliguria may result from the development of acute tubular necrosis rather than ongoing volume depletion. In this context, aggressive rehydration may lead to pulmonary and peripheral edema without enhancing renal function or urine output.34

Patients with adverse prognostic indicators (see above) should be treated in an ICU, based on early stratification of severity. Pancreatic infection correlates with necrotizing pancreatitis, fever, leukocytosis, or organ failure after the first week of illness. Infected necrosis must also be assessed in patients who develop fever, leukocytosis, or organ failure seven to ten days after onset of acute pancreatitis. Current recommendations include use of prophylactic antibiotics in the setting of fulminant pancreatitis with necrosis, at least until CT-guided needle aspiration of pancreatic necrosis and additional investigations for nonpancreatic infection are negative.35 Pooled data from four recent randomized, controlled trials suggest that intravenous antibiotics, especially imipenem, decrease pancreatic sepsis (odds ratio [OR] = 0.51; P = 0.04) and have a beneficial effect on mortality (OR = 0.32; P = 0.02).36 Evidence is lacking to employ age-influenced criteria to determine indications for antibiotic prophylaxis.

Recent data suggest that enteral nutrition (EN) is preferable to total parenteral nutrition (TPN) in patients without ileus who are not expected to tolerate oral feedings for a prolonged period.33 Delivery of nutrients directly into the distal jejunum affects pancreatic secretion minimally as compared to more proximal feeding. Naso-jejunal feedings may improve compromised gut function, increase blood flow, and enhance immune function and protein synthesis. Compared to TPN, jejunal nutrition may strengthen gut mucosal integrity as a barrier to bacterial translocation and subsequent pancreatic infection while avoiding the catheter-related complications of TPN.33 EN may decrease intestinal permeability to cytokines and endotoxin, blunting the systemic inflammatory response accompanying severe pancreatitis. A recent Cochrane review indicates a trend to decreased morbidity with high-protein, low-fat feedings via naso-jejunal, radiologic, or endoscopic placement of jejunal feeding tubes.37 In gallstone pancreatitis, most authorities recommend prophylactic cholecystectomy during the same hospitalization, due to the potential for recurrent attacks. In severe biliary pancreatitis, cholecystectomy may be delayed until resolution of the acute inflammatory process.38 Early ERCP sphincterotomy may be indicated for concomitant cholangitis, persistent common bile duct stones, jaundice, or in episodes predicted to be severe.39 ERCP should be followed by elective cholecystectomy in patients with gallbladder stones who are fit for surgery. Emergent cholecystectomy carries as high as a three-fold increased morbidity and mortality risk in the older patient as compared with elective surgery.40

Conclusion

As the population ages, older adults will present with acute pancreatitis in greater numbers. The structural and functional changes of normal aging must be differentiated from pathologic states. Elevated serum levels of pancreatic enzymes and abdominal pain are nonspecific and must be distinguished from a diverse range of other common abdominal disorders with overlapping features. Conversely, the absence of typical signs, symptoms, or serologic results does not exclude acute pancreatitis. To avoid misdiagnosis and reduce morbidity and mortality, clinicians must be aware of the diverse spectrum of acute pancreatitis in older adults.

Dr. Nanda has been on the speaker’s bureau of Forest Pharmaceuticals, and has received a research grant from Amgen. The other authors report no relevant financial relationships.