Post-Hospital Clinic for Older Patients and Their Family Caregivers

Introduction

In 2003, over 13.2 million persons age 65 years and older were discharged from hospitals.1 Because of their higher prevalence of frailty and slower period of recovery, the transitional period from hospital to home presents major challenges for older patients and their family caregivers.2,3 The first few weeks after discharge abound with issues in symptom management and personal care.4,5 Close surveillance post-discharge may prevent serious adverse outcomes such as rehospitalization and use of emergency care services for patients, as well as undue caregiver stress and burden for their family caregivers.

Because most older adults rely heavily on their family for optimal convalescence at home,6 expanding the focus of surveillance to the patient-caregiver dyad as a unit of care may be a more effective approach. In fact, a recent study about transitions to home conducted by Coleman and colleagues7 showed that coaching of patient–caregiver dyads to ensure that patients’ needs are met after hospital discharge has the potential to reduce the rate of subsequent hospitalizations. This article describes the geriatrics Post-Hospital Clinic (PHC) recently established for geriatric patients and their family caregivers, and uses case examples to illustrate how the structure and function of the clinic have initially benefited these dyads. In 2008, the PHC officially began as a clinical demonstration project and formal measurement of clinical outcomes such as rehospitalization, use of emergency care services, and medication discrepancies; caregiving preparedness is underway.

Post-Hospital Clinic for Older Patients and Their Family Caregivers

Located at the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center in North Carolina, the Geriatric Evaluation and Management (GEM) clinic provides primary care services for approximately 350 older veterans, the majority of whom are age 80 years and older. Given their high rates of comorbid illness and frailty, an average of 2-3 patients require hospital admission each week. These patients are primarily managed by geriatric fellows under the supervision of geriatric faculty, who have clinic sessions one-half day per week. Providers and staff recognized the importance of prompt follow-up appointments for patients with their primary care providers after hospital discharge, but the sheer volume and limited availability of appointments made this a major challenge.

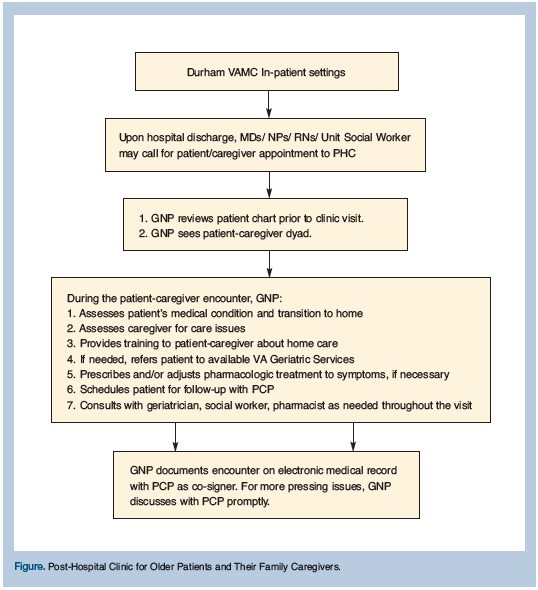

This situation served as the primary impetus to develop a complementary service, the PHC, embedded within the GEM clinic to provide a mechanism whereby older patients and their caregivers can be followed within 1-2 weeks after hospital discharge. The primary provider staffing the PHC is a geriatric nurse practitioner (GNP), who recently joined the GEM team with the specific mission of providing prompt hospital follow-ups and improving patient and caregiver education. A social worker, pharmacist, and geriatrician are available to the PHC from the GEM clinic depending on patient and caregiver needs. The PHC is located in the same facility as the GEM clinic and shares the same electronic medical records. The PHC began in late 2006 (Figure).

Because the point of care focuses on the dyad, an hour is allotted for each scheduled visit. The GNP medically evaluates patients, including medication reconciliation, and assesses, educates, and supports the needs of their family caregivers, all necessary components of effective care transitions.8 In the following sections, a brief description of specific interventions is followed by an illustrative case. However, it should be noted that in most situations, dyads received the full spectrum of interventions and, hopefully, garnered the expected benefits.

Prompt Medical Evaluation to Prevent Worsening of Patient Condition

With aging, the capacity for uncomplicated convalescence diminishes. Older adults suffer from an average of 2 to 3 concomitant chronic illnesses1 that can complicate and impede recovery resulting in possible rehospitalization and/or use of emergency room services. In 2003, overall hospital readmission rate within 30 days of discharge for Medicare home health beneficiaries was 47%, whereas the overall rate of emergency department visits was 30%.9 Additionally, hospitalization, regardless of duration, results in significant functional decline that is associated with poor outcomes at discharge.10

-----

Mr. TS is a 90-year-old gentleman admitted with a community-acquired pneumonia. He was discharged home under the care of his daughter. His medical conditions include hypothyroidism, hemolytic anemia, peptic ulcer disease, hypercholesterolemia, benign prostatic hypertrophy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, and depression. During the PHC visit, Mr. TS stated that he had finished his course of oral antibiotics and his coughing was minimal. However, he also reported feeling increasing fatigue. A complete blood count revealed a hemoglobin and hematocrit of 8.3 gm/dL and 25.4%, a sudden drop from 10.2 and 30.8% obtained prior to his hospital discharge the previous week. The patient had required regular blood transfusions in the past because of his hemolytic anemia. Indeed, the cause of his anemia was confirmed as ongoing hemolysis. He was admitted for an overnight stay to receive blood transfusion and discharged home the following day with a follow-up with his primary care provider in three days. Mr. TS’s daughter expressed gratitude for the visit to the PHC, as this visit facilitated early identification and management of a problem that prevented worsening of her father’s condition.

-----

Medication Reconciliation to Prevent Errors and Complications

Potential for medication error is heightened with lapses in continuity of care occurring during the hospital-to-home transition.11-13 In a study involving 400 patients (age 57 + 17 y) recently discharged from the hospital, Forster and colleagues13 found that 45 (11%) patients developed adverse drug events. Of these, 27% were preventable and 33% were ameliorable. Further, the risk to adverse drug events was found to be related to increased number of prescription drugs. Similarly, when 256 patients age 65 years and older were followed at home after being hospitalized for medical illness, incidence of adverse drug events was 20% and was found to be most common during the first month following hospital stay.14 Among older adults, medication mistakes can have deleterious effects as physiologic changes associated with aging change drug metabolism and excretion significantly. Multiple medications also place the older adults at high risk for drug-drug interactions. Therefore, medication reconciliation is seen as an integral component of patient safety, especially during transitions in care.13,15

-----

Mr. LG, a 79-year-old gentleman, had been admitted to the hospital twice in one month. He had a pacemaker inserted during his first hospitalization, secondary to severe bradycardia. Five days after discharge, he was admitted again to the hospital because of chills and shortness of breath, and received a diagnosis of pneumonia. During the PHC visit, his daughter expressed concern as to whether she was giving the right medications to her father. According to her, the actual medications provided at discharge did not match the written list of orders. She was uncertain whether certain medications were discontinued or just overlooked. The GEM pharmacist was consulted for Mr. LG and upon review of the patient’s discharge medication record, Mr. LG was supposed to be taking a total of 11 different oral medications. Two medication discrepancies were identified: (1) ipratropium bromide/albuterol sulfate inhaler was prescribed, but the patient did not receive it; and (2) finasteride, which the patient has been taking for a number of years, was inadvertently excluded from the list. Not surprisingly, during the PHC visit, Mr. LG reported that he still had persistent shortness of breath. His pulmonary exam revealed an O2 saturation of 94% on room air, and he had minimal wheezes on auscultation. His inhaler and finasteride were restarted. When Mr. LG was checked by phone two days later, he reported an improvement of his dyspnea.

-----

Caregiver Education and Support to Mitigate Caregiver Stress and Burden

Medical advances and shorter hospital stays have transferred the responsibility of the care of frail elderly persons onto their families. Often, family caregivers are expected to assume a health management role in the home and carry out medical tasks that traditionally were performed by healthcare providers, such as wound dressing and catheter care, despite limited discharge preparation.6 Increased preparedness for caregiving is important, as it has been associated with decreased levels of burden and stress among family caregivers.16 High unmet needs of patients predicted negative aspects of caregiver burden.17

-----

Mr. SN is 77 years old and suffers from Parkinson’s disease with limited functional capacity. He was admitted to the hospital because of urinary tract infection (UTI). He was discharged home under the care of his sister, who was devoted to providing the best care for her brother. The patient had an indwelling catheter because of urinary retention secondary to prostate enlargement. An attempt to remove the catheter prior to hospital discharge was unsuccessful. At the PHC visit, his sister was particularly concerned about the possibility of recurrent UTI because of the patient’s indwelling catheter. Further, she stated that she was uncertain on how to assist her brother in keeping his catheter clean. She reported that she has started to notice some “mucus” coming from her brother’s urethral meatus. During the PHC visit, the GNP taught the caregiver and the patient about indwelling urinary catheter care including daily perineal cleaning, proper drainage bag placement, and changing of drainage bags. Signs and symptoms of UTI were reviewed including atypical symptom of infection, such as changes in mental status. Mr. SN’s sister was reassured to learn about proper care for her brother’s indwelling urinary catheter and that a urology consult was in place to follow his readiness for catheter removal. She expressed appreciation and relief that her brother’s healthcare providers are “on top” of his situation.

-----

Provision of Community Healthcare Services to Augment Delivery of Care

Acquiring community services has been found to be beneficial for older patients during transition from hospital to community18 and may, in fact, be a major determinant regarding whether an older adult can continue to live within the comforts of his/her own home. Anticipating post-acute needs and making referrals for follow-up care are crucial to support patients’ transition to home.19 Community resources, however, have been found to be underused in the first week post-discharge.20 The lack of continuity of social work services between settings contributes to this problem and may lead to fragmented services and discontinuity of care.

-----

Mr. FO is an 86-year old patient who has a history of cerebrovascular accident that resulted in right-sided weakness. He was recently admitted to the hospital because of worsening weakness attributed to dehydration. Upon discharge, the patient elected to go home with physical therapy and occupational therapy in place to follow him twice a week. Mr. FO lived by himself, and his nearest relatives were his son and daughter-in-law, who lived an hour away. Despite his neurologic deficits, Mr. FO was able to independently perform his activities of daily living. His wishes were to remain living in his home. His family was requesting additional services to be in place to assist in his care. During the PHC visit, the GEM social worker was consulted and determined that Mr. FO qualified for more community services because of significant co-morbidities such as labile hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, glaucoma, and cerebrovascular accident. Specifically, home health nurses were consulted for cardiopulmonary assessment, home safety evaluation, diabetic assessment, and disease teaching. More importantly, Mr. FO also qualified for telehealth chronic disease management facilitating monitoring his blood pressure and blood glucose in his home. With these additional services in place, Mr. FO was able to remain in his home under close surveillance, and with his family feeling comfortable about his living situation.

-----

The Post-Hospital Clinic: Future Directions

In 2008, the PHC officially began as a clinical demonstration project. Clinic personnel have started to collect patient and caregiver variables to formally measure the project’s impact on the dyad. Outcome variables include rehospitalization and use of emergency care services within one month of hospital discharge, medication discrepancies, and caregiving preparedness among family caregivers. For patient rehospitalization and use of emergency care services, comparisons will be made with historical controls.

Summary and Conclusion

The PHC was developed to establish an early follow-up mechanism for our geriatric patients and their family caregivers after hospital discharge. As this period is replete with challenges, timely attention by a healthcare provider has the potential to avert negative outcomes. To date, specific benefits have been observed among the dyads consistent with prior studies, including early recognition of changes in medical condition, prevention of medication-related problems, appropriate and timely referrals to community services, and caregiver support and education. Detailed outcomes data will further clarify the nature and extent of the impact of the clinic. The authors hypothesize that with prompt attention, adverse outcomes may be prevented among geriatric patients, and that caregivers will feel supported during this important transition in care.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.