Instituting Cognitive Rehabilitation in Post-Acute Care

Instituting Cognitive Rehabilitation in Post-Acute Care

Hospital length of stay is dramatically shorter today than in the past. As a result, many older adults require post-acute care in order to regain lost functioning brought on by acute illnesses. While the emphasis in post-acute care is primarily physical rehabilitation, over two-thirds of older adults admitted to these facilities have at least one delirium symptom.1 Recent evidence supports the strong relationship between the resolution of delirium and functional recovery following hospitalization.2 Little clinical attention, however, has been given to older adults’ need for cognitive rehabilitation following hospitalization.

This article reviews the problem of delirium in post-acute care and its impact on functional recovery following hospitalization. We describe a cognitive rehabilitation program that has been successfully implemented in a skilled nursing setting as part of a total program to prevent and/or treat post-hospital delirium. In long-term care facilities, the program requires collaboration between the medical director, nursing staff, and recreational therapist to maximize functional recovery, and potentially reduce the cost of care for older adults who have suffered an acute illness. We list strategies for achieving program effectiveness through interdisciplinary collaboration.

Delirium in Post-Acute Care

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition), delirium is a common, though frequently unrecognized and untreated, neuropsychiatric syndrome in older adults that is characterized by a sudden decline in attention and cognition.3 Delirium frequently accompanies acute medical conditions and carries a high rate of morbidity and mortality; among hospitalized older adults, mortality can be as high as 76%.4 In a recent review of the state of the science on delirium, Inouye5 notes that delirium typically involves complex interrelationships between a vulnerable patient and exposure to noxious stimuli. The presence of dementia, depression, dehydration, immobility, sensory impairment, multiple comorbidities, and certain classes of drugs are risk factors for delirium.

Recent evidence suggests that the relationship between delirium and dementia is much more important than previously thought. While delirium itself does not seem to cause dementia, its occurrence in hospitalized older adults may herald the onset of dementia. Most cases of delirium occur in persons with dementia,5-7 and 89% of hospitalized persons with dementia will experience delirium.8,9 The two conditions have overlapping clinical, metabolic, and cellular mechanisms, suggesting that delirium and dementia may represent points along a continuum.5 Delirium persists much longer in the post-hospital period than previously recognized, and may reflect underlying brain vulnerability in older adults with very-early-stage dementia.5

Because hospital length of stay is now considerably shorter than in the past, studies indicate that between 16% to 23% of older adults may be discharged with delirium,1,10 shifting the care and cost of care for these individuals to post-acute care facilities. Older adults who are admitted to post-acute care with delirium experience more complications, re-hospitalizations, and death compared to those without delirium.11 Additionally, older adults whose delirium resolves more slowly, or never at all, regain no more than 50% of their pre-hospital functioning, while those whose delirium resolves within two weeks of admission to post-acute care recover all of their pre-hospital functioning.2

Cost of care is disproportionately higher in older adults with delirium. In a retrospective study of 76,688 community-living older adults, the majority of the initial delirium claims occurred in acute-care stay or emergency room visits. Persons with delirium superimposed on dementia (DSD) had the highest total healthcare costs, the largest number of acute-care stays, and the highest number of skilled short-stay nursing home admissions over a three-year period.12

Given these data, efforts to prevent delirium should be a priority of care for all older adults admitted to acute-care facilities. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is one of the few delirium prevention models to explicitly use cognitive interventions as part of an approach to improve cognitive and physical functioning and prevent delirium in hospitalized older adults. HELP uses daily visits by volunteers supplemented by cognitive activities such as reminiscence, trivia, and current events. HELP also targets sleep deprivation, immobility, visual and hearing impairments, and dehydration. While the cognitive component has not been evaluated by itself, the total HELP program has been successful in preventing delirium in hospitalized older adults.13-15

It is important that cognitive rehabilitation continue following hospital discharge given the high rate of persistence of delirium in post-acute care. Shortening the post-hospital length of stay and preventing hospital readmissions with programs using cognitive rehabilitation is important for older adults’ health and quality of life, and is a source of cost-savings potential for this population.

Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation is an individualized approach that uses nonpharmacological interventions for improving specific domains of cognitive function; the goal is not cognitive enhancement but improvement in cognitive function in the everyday context.16 Our initial experience with cognitive rehabilitation occurred in The Center for Positive Aging (CFPA), a community setting in Southwest Florida that is housed within a large senior center. The CFPA provides a range of programs and services to older adults in the community, especially those with cognitive impairments. In the delivery of services, we observed the negative impact of hospitalization on older adults who were clients of the CFPA. It was not unusual for families to report significant loss of cognitive functioning in the older adult after hospitalization, and many of these older adults never returned to the CFPA following the acute illness. To address this problem, we developed a clinical program of cognitive rehabilitation that we delivered to the site of post-acute care. These sites are most often skilled nursing centers, but can also be assisted living or in-home sites.

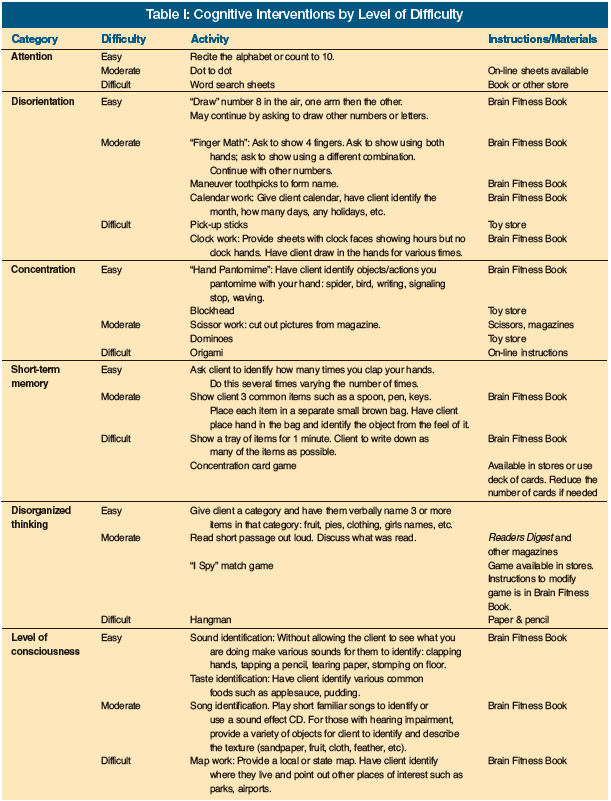

Most interventions for the prevention/treatment of delirium are multifaceted, targeted at risk factors, and generally include a cognitive component.13,17,18 The goal of our cognitive intervention is to promote alertness, orientation, attention, concentration, short-term memory, and organized thinking—cognitive functions that are affected by delirium.

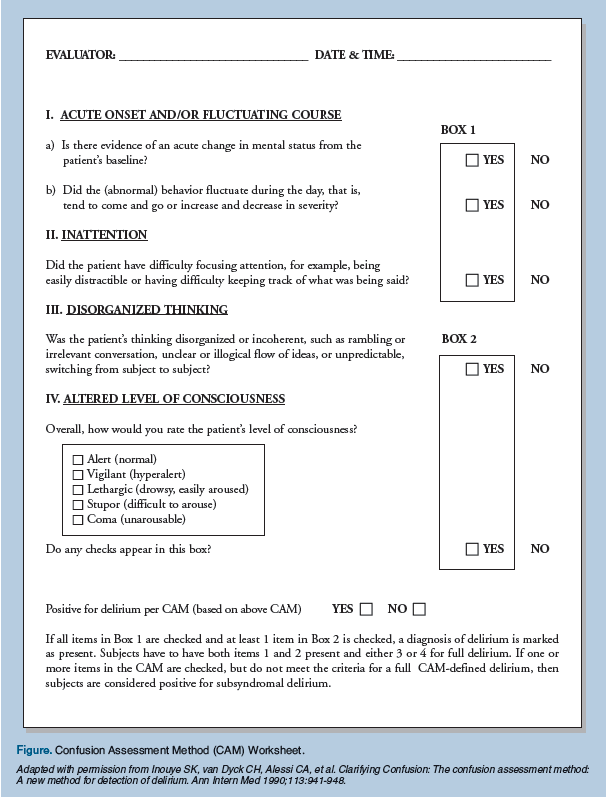

Cognitive rehabilitation begins with an assessment of the older adult’s cognitive status upon admission to post-acute care. This is usually initially done by the social worker, but should continue on a daily basis thereafter by nursing or recreational therapy, as these two disciplines are primarily responsible for day-to-day assessment and intervention. There are several instruments that can be used for initial assessment as well as documentation of resolution of the delirium. The most widely used and clinically friendly instrument for measuring delirium is the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM),19 a standardized screening algorithm that enables persons without formal psychiatric training to quickly and accurately identify delirium (Figure). The CAM has descriptors that capture four features of the syndrome: (1) acute onset and fluctuating course, (2) inattention, (3) disorganized thinking, and (4) altered level of consciousness. The presence of 1, 2, and either 3 or 4 confirms a delirium. The CAM was validated against geriatric psychiatrists’ ratings using DSM-III-R criteria and has been shown to have a sensitivity between 94% and 100% and a specificity between 90% and 95%.19,20 Studies have demonstrated the utility of a daily CAM in identifying delirium and the waxing and waning states in delirium.21-24

Daily assessment should continue until the delirium is resolved, using a structured interview and direct observation, guided by the CAM criteria and supplemented with a test of attention such as spelling WORLD backwards or subtracting 3 from 20 (items from the Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE]25 or the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire26). Delirium should be recorded as present or absent each day based on the CAM. Delirium may also be described as subsyndromal, meaning that at least one feature is present (Figure). Persistent subsyndromal delirium has been shown to be associated with poor outcomes.2,5

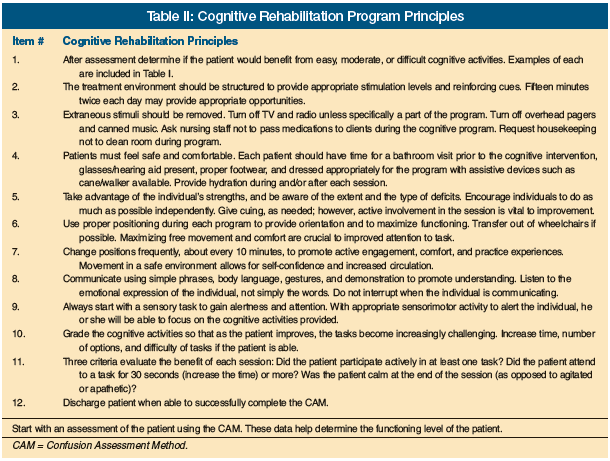

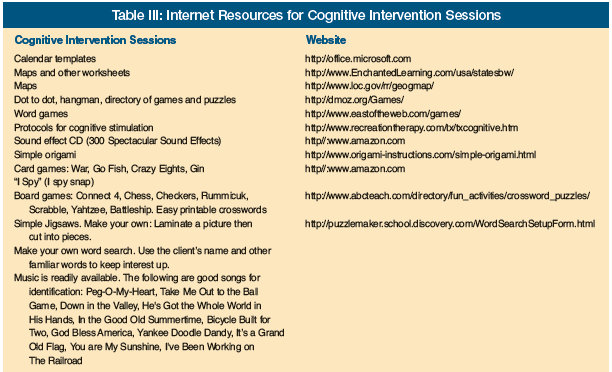

Based on the initial assessment, a cognitive rehabilitation program is tailored to the older adult’s level of cognitive functioning, starting with the easiest level of tasks and increasing the level of difficulty as success occurs with the simpler tasks. The program we present here has been developed and used in long-term care and post-acute settings by two of the authors, Dr. Buettner and Ms. Fitzsimmons. Specific cognitive interventions target attention, orientation, concentration, short-term memory, and organized thinking and are described in Table I. Principles for implementing the interventions are outlined in Table II. In general, interventions are designed to be stimulating, challenging, novel, and fun but not frustrating. They should be active and goal-driven. For example, older adults are encouraged to read aloud, point out facts, describe things, ask questions, answer questions, or make choices. Those with language deficits might be involved in other types of cognitive activities, such as solving increasingly difficult puzzles or following step-by-step directions in a therapeutic cooking program. Animal-assisted therapy tasks might be used to engage an older adult in cognitive activities even while in bed. At times, cognitive interventions are passive in nature. If an older adult is highly distracted and unable to focus, the goal might be simply to concentrate on a form of stimulation for a short period of time. Examples include listening to music or a poem being read. Table III lists several websites that provide a number of the cognitive interventions described in Table I, as well as other resources.

As the interventions are implemented, it is vital that the therapist documents improvements on a daily basis and reports these changes to all staff at unit meetings. Staff need to be informed of specific cognitive interventions that work to alert and engage the older adult so these interventions can be incorporated into their plan of care. Staff should understand the importance of avoiding interruption during implementation of the cognitive interventions so the older adult can obtain the maximum benefit.

Strategies for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

We believe a systematic program of cognitive rehabilitation should be integrated into the older adult’s plan of care, when appropriate, as part of a comprehensive approach to the assessment, prevention, and management of a delirium. As is true of all therapies, there first needs to be staff and administration buy-in if the intervention is to be effective. An excellent way to facilitate buy-in is for the medical director, in conjunction with nursing and recreational therapy, to provide a series of in-service programs for staff and administration that present the impact of delirium on health outcomes, the assessment process and methods for using screening tools for high-risk older adults, and the prevention and management processes that incorporate all treatment modalities, but especially cognitive rehabilitation. The benefits and the improvements that might be expected of cognitive interventions can be related to reduction in staff burden, and direct care staff can be asked for referrals.

A comprehensive approach to delirium in the facility necessitates the development of a process that incorporates specific policies in the facility and collaboration between the entire interdisciplinary team, but especially the medical director, primary care clinician, nursing, and recreational therapy. The medical director is responsible for overseeing policies related to overall quality of care, implementation of resident care policies, and the coordination of medical care in the facility.27 Thus, when bringing the cognitive rehabilitation intervention into a comprehensive process of assessment, prevention, and management of delirium, the medical director, nursing, and recreational therapy should:

• Collaborate in the development of the process, writing of the policies and follow-up on the progress of the program

• Look at the process on rounds and via record review

• Actively advocate, when necessary, for improvements in the process and quality of delirium care in general

• Be actively involved in studying delirium care via the quality assurance process/meetings

• Act as a knowledge base resource for the evolvement of the program

Summary of Clinical Observations

We recognize that the cognitive rehabilitation program we describe here is based on clinical experience. We are encouraged, however, by our clinical observations: chart reviews at the CFPA that spanned a 1-year period of time revealed that eight of the nine (89%) older adults who were discharged from the hospital and who received the cognitive rehabilitation program returned to their pre-hospital community programs at the CFPA, in contrast to 14 of the 22 (64%) older adults who did not receive the program. Of the older adults who returned to the community programs at CFPA following hospitalization, those who participated in the cognitive rehabilitation program returned approximately 3 weeks sooner than those who did not participate. We also observed that the mean MMSE change for older adults in the program who returned to the CFPA was a decline of 0.5 point (20.5 [SD = 3.54] pre-hospitalization to 20.0 [SD = 4.20] post-1-month return) versus a 3-point decline for older adults who did not participate in the program (18.5 [SD = 6.26] pre-hospitalization to 15.5 [SD = 6.38] post-1-month return).

Our clinical observations indicate that the cognitive rehabilitation program we instituted holds promise for improving recovery following hospitalization, but there is a need to systematically test the program in post-acute care. A number of recent trials have demonstrated the efficacy of cognitive interventions on outcomes for persons with dementia, but without delirium.28-30 Results indicate that cognitive stimulation improves global cognition, functional abilities, and emotional symptoms, as compared to control, when used alone or in combination with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. However, based on the extent of the problem of delirium following hospitalization and the clinical success of several cognitive rehabilitation programs, we encourage staff in post-acute facilities to adopt these programs in an effort to shorten recovery time, reduce costs, and improve quality of life for older adults who experience delirium.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgments Drs. Kolanowski and Buettner are supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research: R01 NR008910 (A. Kolanowski, PI). Dr. Fick is supported in part by a grant from the National Institute on Aging: R03 AG023216. For more on the Confusion Assessment Method, visit the Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing website at https://hign.org to access the “Try This” assessment tool (also available in the January 2008 issue of Annals of Long-Term Care.)