Older Lesbians and Gay Men: Long-Term Care Issues

Recognizing and responding to the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender elders will promote better services for ALL elders because it promotes sensitivity and respect for diversity in all its aspects, as well as creating a space where sexuality and aging in general can be explored and discussed --Quam (n.d.)

Introduction

Similar to other aging Americans who are constrained by ageist stereotyping and misconceptions, older lesbians and gay men face such problems as loss of family and friends, health concerns, increased isolation from community, fear of dependency, and reduced income.1 Older lesbians and gay men may experience additional challenges as they approach mainstream health and social service agencies and programs. As young and middle-aged adults, lesbians and gay men experienced structural and institutional homophobia, heterosexism, and anti-gay violence in healthcare, housing, employment, and civil rights.2 Now as older adults, they also experience inequality and disparity because of unequal coverage for same-sex couples under policies regulating Social Security and private pension plans.3 When the caregiving needs of older lesbian and gay men can no longer be met by trusted partners, friends, and relatives, they may be reluctant to access traditional community-based and institutional long-term care (LTC) services.4 Unrecognized caregiving needs, concerns about affordable housing, and real or anticipated homophobia and heterosexist attitudes by agency staff in LTC facilities further marginalize older lesbians and gay men5 and can compromise their quality of care.

Demographics

Current demographic trends reveal that the U.S. population is aging. The gay and lesbian population over 65 is also aging,6 and by 2030, there will be 4-6 million older lesbian, gay, and bisexual people.7 This approximation is conservative because neither the U.S. Census Bureau nor other population studies ask about sexual orientation. Based on the commonly used estimate that 3-5% of the older population utilizes nursing home care,8 by 2030 between 120,000 to 300,000 older lesbians and gay men will reside in nursing homes across the United States, while others will reside in the community with the support and assistance of friends, family, and utilization of health, social service, and community-based LTC services.

Although there is a lack of information about specific demographic characteristics of this population, what is known is that this older lesbian and gay population is heterogeneous. In addition to cultural, ethnic, and racial diversity, older lesbians and gay men differ in other factors such as education, income, abilities, history of partnerships (including previous heterosexual marriage), length of current or past same-sex relationships, children, age and experience of coming out, and the degree of identification as gay or lesbian.9 The life course perspective emphasizes the diversity of life paths of individuals and recognizes the impact of historical events on age cohorts.10 Regardless of their diversity, older lesbians and gay men share a common history of discrimination, such as rejection, oppression, invisibility, and threats of violence.11

History of Oppression

Older lesbians and gay men are sometimes referred to as the “pre-liberation” generation who were labeled “sick by doctors, immoral by clergy, unfit by the military, and a menace by the police.”12 For them the “the heavy moral, social and legal injunctions against homosexuality have weighed heavily.”13 Hutchison10 emphasizes that the life course perspective links childhood and adolescent experiences with later experiences in adulthood.

Heterosexism or homophobia created hostile environments for lesbians and gays in the past, and these forms of oppression still permeate our society and affect the quality of life of older lesbians and gay men. Heterosexism is a system of beliefs and attitudes “that denies, denigrates, and stigmatizes any non-heterosexual form of behavior, identity, relationship or community.”11

Homophobia is an irrational fear and hatred of people because of their sexual orientation.14 In addition to experiencing homophobia and heterosexism in the larger community, older lesbians and gay men often confront ageism in the lesbian and gay community.15 Although society is more open and accepting of sexual diversity than before the Gay Liberation Movement began in the early 1970s, older lesbians and gay men may still carry scars from their experience of discrimination and stigmatization.16

Marginalized in Healthcare and Social Services

Many health and social service providers lack awareness of and knowledge about long-term care needs of the lesbian and gay population, about how to provide culturally sensitive and affirming services and programs, and about ways to increase accessibility and acceptability of long-term care options for lesbian and gay older adults. The needs of older gay men who Berger17 referred to as “gay and gray” and older lesbians who Kehoe18 called the “triple invisible minority” (female, old, gay) have been excluded from research and practice.1

Anti-gay bias has been recognized by the Gay & Lesbian Medical Association since 1994, when medical professionals and students reported hearing negative and disparaging comment about lesbians, gay, bisexuals and transgender people.19 As a result, older lesbian and gay adults may mistrust the health, social service, and aging services delivery network, and may refuse or be reluctant to access them20 even when their health and safety is at risk. Victimization of older adults, including elder abuse (physical, emotional, sexual), financial exploitation, neglect, and abandonment, is perpetrated by spouses, partners, adult children, and staff in LTC facilities, and it has been documented in the gerontological literature.8 What has not been researched is “victimization based on sexual orientation [as] an additional form of elder abuse that can occur simultaneously with other types of elder abuse.”2 The fear of discrimination and disclosure, plus the risk of victimization, may increase the vulnerability of older lesbians and gay men.

Marginalized in Research

]A growing, but limited, body of research on older lesbians and gay men has begun to emerge; however, most studies utilize small samples, are nonrepresentative, do not reflect ethnic and racial diversity, and recruit from gay-friendly religious and social organizations.16 The research has been criticized for its attention to upper-middle-class, white, well-educated gay men who are active in the gay community.21 Other methodological issues, such as inconsistency in defining age cohorts22 and failure of researchers to employ strategies to ensure validity and reliability, have created additional challenges in research with older lesbians and gay men.

Research findings for some diverse groups are available. For example, cancer rates differ for heterosexual African-American and white women. Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer for all heterosexual women in the United States; however, the second most commonly diagnosed cancer for African-American women is colon and rectum cancer, while white women are more often diagnosed with lung cancer.

Research is desperately needed to ascertain the cancer diagnosis rate and effective prevention strategies for lesbians, who may have never given birth, used oral contraceptives, or even had regular physician exams.7 Research about lesbians and gay men has previously lacked funding and recognition by the mainstream research community.23 In March 2006, however, the Department of Health and Human Services, through the National Institute of Mental Health, released a Program Announcement (RO1) inviting grant applications under the category “Health Research with Diverse Populations,” which included research affecting the health of lesbians and gay men and related populations. Including lesbians and gay men as a research population is an important step forward by the federal government. Nonetheless, there are many challenges in applying and receiving federal funding for what many gerontologists view as a politically controversial, special interest, or fringe group.

What We Know About Older Lesbians and Gay Men

As with older adults, myths and stereotypes about older lesbians and gay men reflect negative characteristics, such as loneliness, lack of companionship, dissatisfaction with their lives, and absence of satisfying sexual relationships.23 Current research indicates that older lesbians and gays are less likely to be living with life partners or their children and are more likely to live alone than their heterosexual counterparts.7 Although they are more likely to live alone, they do not necessarily report feeling lonely and isolated. In contrast to the myth of loneliness, older lesbians and gay men are no lonelier than their heterosexual counterparts or younger lesbians and gay men. Social networks, sometimes called “family of friends” or “families of choice” that older lesbians and gay men have developed, may provide a buffer during times of loss and need.14 Studies of older gay men17 and older lesbians24 show that they desire companionship and involvement in satisfying sexual relationships, as do heterosexual people.

Common Fears

Recent studies describe the health, social service, and LTC needs of older lesbians and gay men in various geographic locations: Chicago,25 Canada,26 rural Maine,27 California,22 and mid-Atlantic states.28 The locality in which these studies were conducted differed but two themes emerged consistently: Fear of discrimination and fear of disclosure prevented utilization of needed services. Although no studies explore how older lesbians and gay men negotiate their multiple identities when they transition from the community to LTC, fear of discrimination and fear of disclosure might well apply to this population as they access LTC and/or move into LTC facilities.

Studies reveal that some older lesbians and gay men are willing to access generic health and LTC services through mainstream organizations when the aging service network is aware, understands, and is prepared to meet their unique needs.29 Because culturally sensitive services are not consistently available, the importance of partners and friends is underestimated or ignored, and older lesbians and gay men do not seek or receive needed services. Some older lesbians and gay men may chose to move to an exclusive lesbian and gay retirement community; however, many will have reasons to stay in their local communities because of financial resources, straight friends or coworkers, family members, or lack of desire to live in a segregated community.

Coping Strategies

In negotiating between the heterosexual society and the homosexual community, some older lesbians and gay men have developed “crisis competence”30 or “stigma management”28 as they have learned to address the environmental pressures in their lives. While many older gay men and lesbians are “described as psychologically well adjusted, vibrant, and growing older successfully,”1 some struggle with their aging. A lack of research about the health concerns of lesbians and gay men contributes to these struggles. In fact, except for HIV, healthcare issues among midlife and older lesbians and gay men urgently need attention.

Despite the victimization, many lesbians and gay men have learned ways to master the minority stress and stigmatization imposed by the external environment. They develop internal resources and external supports, leading to resiliency.20 Yet some of their adaptive coping mechanisms that served as protective factors when they were younger—avoiding identification of themselves and their partners to others, avoiding identification with the lesbian and gay communities, and avoiding services—may not be life-affirming as they get older.31 The decision to conceal one’s sexual orientation, based on fear and anxiety, may prevent them from receiving appropriate services.

Retreat to the Closet

Like older adults in general, older lesbians and gay men may struggle with developmental tasks associated with successful aging, such as claiming pride with their life’s accomplishments, finding meaning in their lives, and engaging in social and productive activities.11 Because of the limitations on aging services that address the specialized needs of older lesbians and gays; however, many hide their sexual orientation when they are faced with dependency on agencies and services. The concern that these experiences and threats of prejudice, marginalization, and physical harm will persist and affect their quality of care is increased.

Older lesbians and gay men “often find themselves having to [go] back into hiding,”26 when they became ill, vulnerable, and dependent on others.2 The decision to return or not to return to the closet demonstrates the interplay between human lives and historical times, human agency in decision making, the diversity of the life experiences, and the impact of earlier events and transitions on current and future transitions,10,32,33 which are themes reflected in the life course perspective. It is particularly troubling when older lesbians and gay men, who have previously lived fully or partially open lives, decide they must hide a critical part of their identity (ie, their sexual orientation) in order to feel physically and emotionally safe in nursing homes, assisted living facilities, or retirement communities.34,35

Concealing their sexual identity limits lesbians’ and gay men’s ability to integrate their life experiences across their lifespan and to make meaning of their lives. This concealment creates a potential tension, because if previously open older lesbians and gay men decide to retreat to the closet to feel safe, then culturally competent health and social service practitioners cannot address the challenges and barriers facing them. Although it is not clear whether the retreat to the closet is internally or externally motivated,35 many older lesbians and gay men fear homophobic attitudes from staff and other residents, and as a result, their needs may go unrecognized.4 Even those “who had open relationships, who were active in the community, and who were comfortable with their identity were often unwilling to open themselves up to additional vulnerabilities that accompany coming out.”15

Examples of homophobia among nursing home staff include refusal to bathe “the lesbian” and workers threatening to reveal a resident’s lesbian identity to other residents and to staff.3 A lifelong relationship may be negated during a medical crisis, when gay couples are separated into different nursing homes, without regard for their long-term relationship.36 Other lesbians and gay men agonize about accessing LTC services “because they worry that their integrity and their life choices will not be honored…and their long term partnerships may not be recognized or valued.”11 Same-sex partners are often denied visitation privileges in hospitals and LTC facilities, and chosen families are often excluded from making decisions about an older lesbian or gay man’s care in LTC facilities.29 In fact, “people have been prepared to die at home without sufficient care, rather than go back into the closet in order to enter an otherwise appropriate nursing home setting.”37

Long-Term Care: Challenges and Opportunities

While for many ethnic individuals and heterosexuals, the family of origin serves as a protection against an oppressive society, some lesbians and gay men have found their home and nuclear family a place of rejection and hostility. As a result, lesbians and gay men have likely developed a network of close friends or chosen families of choice to whom they can turn when in need,31 but “society has not always acknowledged the importance of these ‘chosen families.’”38 Therefore, it is imperative for health care practitioners to understand that a move to a nursing home for an older lesbian and gay man may mean the loss of a supportive community, making it more difficult to adjust to the new, and potentially hostile, environment. In addition to social discrimination, this population faces income discrimination in the form of unequal financial factors, such as retirement income, Social Security, private pensions, and Medicaid. Older lesbians and gay men are not eligible for the Social Security survivor benefits when a loved one dies.39 Although some older lesbians and gay men may be covered under domestic partner benefits for healthcare, they are not eligible to receive retirement benefits or Medicaid spousal impoverishment protection.28

Ethical Mandates

Social workers, nurses, and LTC administrators have an ethical responsibility to treat all people with respect and dignity. In the state of Texas, LTC administrators are governed by directives from the Department of Aging and Disability Services (DADS). DADS mandates continuing education for LTC administrators and requires annual continuing education content on business and management practices, resident care, and ethics. Tolerance for resident and family diversity is highlighted. Social work’s core values of service, social justice, dignity and worth of the person; importance of human relationships; and integrity and competence mandate that social workers adhere to ethical standards in practice, research, and education. Through the more recent versions of the Council on Social Work Education Educational Policy and Accreditation Standards40 and the National Association of Social Work Code of Ethics,41 the profession of social work has reaffirmed its devotion to addressing issues of social justice associated with sexual orientation.42 Both the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the American Association of College of Nursing (AACN) support ethical nursing practice. The first of nine revisions in the ANA Code of Ethics emphasizes “compassion and respect for the inherent dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual."

Core professional values cited in the AACN Essentials of Baccalaureate Education include altruism, autonomy, human dignity, integrity, and social justice. Core knowledge required for professional nursing practice includes human diversity and lifestyle variations in which the professional nurse is a client advocate, sensitive to the needs of individual patients or vulnerable populations.43 From the brief descriptions above, it is clear that LTC administrators, social workers, and nurses are required to achieve similar ethical competencies related to marginalized and vulnerable clients. However, some providers may not be aware of the heterosexual assumptions and homophobia that construct barriers to welcoming and inclusive services and settings for older lesbians and gay men, or may not have thought about these issues previously.

Affirming Practices

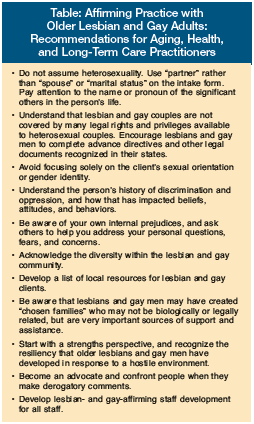

An organizational approach for mainstream health and social service agencies and LTC facilities to demonstrate affirming practice is developing “statements of nondiscrimination that include sexual orientation,”44 which can affect agency policy and practice. Healy14 identifies four guidelines for providing culturally sensitive services: awareness, combat heterosexist assumptions, learn about culturally competent practice, and utilize inclusive language and actions for culturally sensitive affirmative practice. Anetzberger45 suggests initiating conversations with staff and administrators about gay and lesbian issues that may affect quality of care and providing a “mechanism for hearing directly from older gays and lesbians regarding what they perceive as their needs, concerns, issues, and service preferences.43 Other recommendations can be found in the Table.

An organizational approach for mainstream health and social service agencies and LTC facilities to demonstrate affirming practice is developing “statements of nondiscrimination that include sexual orientation,”44 which can affect agency policy and practice. Healy14 identifies four guidelines for providing culturally sensitive services: awareness, combat heterosexist assumptions, learn about culturally competent practice, and utilize inclusive language and actions for culturally sensitive affirmative practice. Anetzberger45 suggests initiating conversations with staff and administrators about gay and lesbian issues that may affect quality of care and providing a “mechanism for hearing directly from older gays and lesbians regarding what they perceive as their needs, concerns, issues, and service preferences.43 Other recommendations can be found in the Table.

Conclusion

While communities, policy makers, and health and social service organizations struggle with how to prepare for the increasing demands of an aging population, more research is needed to better understand the challenges and barriers experienced by of older lesbians and gays in accessing and utilizing LTC. Because of the heterosexist and hostile environment that existed for this population when they were younger, and may still exist for many older members of the lesbian and gay populations, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners adhere to their profession’s guidelines for cultural competency. Most significant is the protection of these individuals from exploitation and harm while participating in research projects. Cultural sensitivity training for LTC facility staff, residents and their families can assist LTC facilities to provide an environment where older lesbians and gay men do not need to fear or to hide, but can experience the same quality of life of older adults in general. More research and practice strategies are necessary to insure the presence of ethical policies and practices ending discrimination against older lesbians and gay men and create welcoming and affirming environments, positively affecting the dignity of and respect for all older adults.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

References

1. Barranti C, Cohen H. Lesbian and gay elders: An invisible minority. In: Schneider R, Kropf N, Kisor A, eds. Gerontological Social Work: Knowledge, Service Settings and Special Populations. Volume 2nd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 2000:343-367.

2. Balsam KF, D'Augelli. The victimization of older LGBT adults: Patterns, impact and implications for intervention. In: Kimmel D, Rose T, David S, eds. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Aging: Research and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006:110-130.

3. Cahill S. Long term care issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. Geriatric Care Management 2002;12(3):3-9.

4. Sales AU. Back in the closet. Community Care 2002;1424:30-32.

5. Hu M. Selling Us Short: How Social Security Privatization Will Affect Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Americans. Washington, DC: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute; 2005.

6. Kimmel D, Rose T, David S, eds. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Aging: Research and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006.

7. Cahill S, South K, Spade J. Outing age: Public policy issues affecting gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender elders. New York: National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute, 2000.

8. Hooyman NR, Kiyak HA. Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson Education; 2005.

9. Cohen HL, Padilla YC, Aravena VC. Psychosocial support for gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender people. In: Morrow D, Messinger L, eds. Sexual Orientation and Gender Expression in Social Work Practice: Working with Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender People. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006:153-176.

10. Hutchison ED. Dimensions of Human Behavior: The Changing Life Course. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2008.

11. Butler SS. Older gays, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender persons. In: Berkman B, D'Ambruoso S, eds. Handbook of Social Work in Health and Aging. Oxford: University Press, 2006:273-281.

12. Kochman A. Gay and lesbian elderly: Historical overview and implications for social work practice. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 1997;6(1):1-10.

13. Quam JK. Gay and lesbian aging. SEICUS Report 2001;21(5):10-2.

14. Healy TC. Culturally competent practice with elderly lesbians. Geriatric Care Management 2002;12(3):9-13.

15. Altman C. Gay and lesbian seniors: Unique challenges of coming out in later life. SIECUS Report 1999;27(3):14-17.

16. Donahue P, McDonald L. Gay and lesbian aging: Current perspectives and future directions for social work practice and research. Families in Society 2005;86(3):359-366.

17. Berger RM. Gay and gray: The Older Homosexual Man. 2nd ed. New York: Harrington Park Press; 1996.

18. Kehoe M. Lesbians over 65: A triple invisible minority. Journal of Homosexuality 1986;12:139-152.

19. Schatz B, O'Hanlan K. Anti-gay discrimination in medicine: Results of a national survey of lesbian, gay, and bisexual physicians. San Francisco, CA: American Association of Physicians for Human Rights, 1994.

20. Boxer AM. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual aging into the twenty first century: An overview and introduction. Journal of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Identity 1997;2(3/4):187-197.

21. Quam JK, Whitford GS. Adaptation and age-related expectations of older gay and lesbian adults. Gerontologist 1992;32(3):367-374.

22. Jacobs RJ, Rasmussen LA, Hohrman MM. The social support needs of older lesbians, gay men and bisexuals. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 1999;9(1):1-29.

23. Butler SS. Guest editorial message: Geriatric care management with sexual minorities. Geriatric Care Management 2002;12(3):2-3.

24. Clunis DM, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Freeman PA, et al. The Lives of Lesbian Elders: Looking Back, Looking Forward. Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press; 2005.

25. Beeler JA, Rawls TW, Herdt G, Cohler BJ. The needs of older lesbians and gay men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 1999;9(1):31-49.

26. Brotman S, Ryan B, Cormier R. The health and social service needs of gay and lesbian elders and their families in Canada. Gerontologist 2003;43(2):192-202.

27. Butler SS, Hope B. Health and well-being for late middle-aged and old lesbians in rural areas. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 1999;9(4):27-46.

28. McFarland PL, Sanders S. A pilot study about the needs of older gays and lesbians: What social workers need to know. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 2003 40(3):67-79.

29. Zodikoff B. Services for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender older adults. In: Berkman B, D'Ambruoso S, eds. Handbook of Social Work in Health and Aging. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:569-575.

30. Kimmel DC. Adult development in aging: A gay perspective. Journal of Social Issues 1978;34:113-130.

31. Grossman AH. Physical and mental health of older lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. In: Kimmel D, Rose T, David S, eds. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Aging: Research and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press; 2006:53-69.

32. Elder GH. The life course and human development. In: Lerner RM, ed. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1 Theoretical Models of Human Development. 5th ed. New York: John Wiley, 1998:939-991.

33. Hareven TK. Aging and generational relations: A historical and life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 1994;20:437-461.

34. Connolly L. Long term care and hospice: The special needs of older gay men and lesbians. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 1996;5(1):77-91.

35. Walker CA, Curry LC, Hogstel MO. Relocation stress syndrome in older adults transitioning from home to a long-term care facility: Myth or reality? Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 2007;45(1):1-8.

36. Quam JK, ed. Social Services for Senior Gay Men and Lesbians. New York: Haworth Press; 1997.

37. Hayden G. Gray and gay: Helping elders stay out of the closet. Long Term Care Interface 2003:28-32.

38. LGBT Aging Project. LGBT aging project: A 3-year plan and a call for action . Accessed July 25, 2005.

39. Dubois MR. Legal concerns of LGBT elders. In: Kimmel D, Rose T, David S, eds. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Aging: Research and Clinical Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006:195-205.

40. Council on Social Work Education. Educational policy and accreditation standards. Alexandra, VA: Author; 2001.

41. National Association of Social Workers. Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: Author; 2000.

42. Van Voorhis R, Wagner M. Among the missing: Content on lesbian and gay people in social work journals. Social Work 2002;47(4):345-354.

43. American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The essentials of baccalaureate education for professional nursing practice. Washington, DC: Author; 1998.

44. Edwards DJ. Outing the issue. Nursing Homes: Long Term Care Management 2001;50(8):40-44.

45. Anetzberger GJ, Ishler KJ, Mostade J, Blair M. Gray and gay: A community dialogue on the issues and concerns of older gays and lesbians. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 2004;17(1):23-45.