Optimal Aging, Part II: Evidence-Based Practical Steps to Achieve It

The second of a two-part article from the author on optimal aging. Part I appeared in the November issue of the Journal.

Using a systems approach, one may conceive of interventions to promote optimal aging as those that are under the control of the individual and those that must occur at a broader societal level. This article will not address those interventions that could occur at a molecular or genetic level, as the subject is quite speculative. Instead, using the health field model, this article focuses on specific activities a person could undertake, and those that call for expansion or creation of societal solutions. Of course, it must be recalled that the majority of interventions in our society regarding health are focused on disease. The Institute of Medicine's report "The Future of the Public's Health in the 21st Century" states that although as much as 95% of healthcare spending goes to medical care and biomedical research, lifestyle behavior and environment are responsible for more than 70% of avoidable mortality.1 Hence, much of optimal aging is under the individual’s control; however, ideally, society provides support and assistance in helping its members achieve optimal aging.

BIOLOGICAL RESPONSES

The primary biological activities or factors shown to increase the chance of aging optimally are exercise, nutrition, sleep, avoidance of disease-causing agents, practicing preventive medicine, early treatment of diseases and medical conditions, and avoidance of iatrogenic complications.

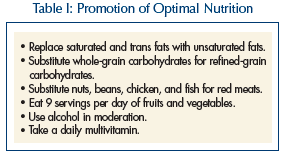

Poor nutrition and weight loss is associated with excess mortality, frailty, and a loss of quality of life.2 Nutritional interventions play a major role in disease management and have been shown to limit the progression of disease. Evidence is accumulating, however, that fad diets, especially if one is cycling on and off various diets, is detrimental to health. Rather, a healthy nutritional strategy is to follow a small set of rules (Table I). A new “food pyramid” based on these principles is presented by Walter Willett in his book on nutrition, Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy.3 Dietary interventions may decrease the risk or progression of macular degeneration, stroke, heart attacks, and lipid abnormalities, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, and a number of cancers. While there is also growing evidence of the risk of taking large doses of vitamins or minerals,4 older people would most likely benefit from a daily multivitamin containing folic acid and vitamins B6, B12, D, and E, as this population is often deficient through dietary intake.5

Poor nutrition and weight loss is associated with excess mortality, frailty, and a loss of quality of life.2 Nutritional interventions play a major role in disease management and have been shown to limit the progression of disease. Evidence is accumulating, however, that fad diets, especially if one is cycling on and off various diets, is detrimental to health. Rather, a healthy nutritional strategy is to follow a small set of rules (Table I). A new “food pyramid” based on these principles is presented by Walter Willett in his book on nutrition, Eat, Drink, and Be Healthy.3 Dietary interventions may decrease the risk or progression of macular degeneration, stroke, heart attacks, and lipid abnormalities, osteoarthritis and osteoporosis, and a number of cancers. While there is also growing evidence of the risk of taking large doses of vitamins or minerals,4 older people would most likely benefit from a daily multivitamin containing folic acid and vitamins B6, B12, D, and E, as this population is often deficient through dietary intake.5

Maintaining a healthy body weight has also been shown to promote optimal aging. Effect size for the relationship between optimal aging and having a normal body weight ranges from 1.58 to 3.05.6 Weight loss has been shown to improve functional status and ameliorate frailty in obese elderly persons.7 Weight maintenance is closely tied to physical activity (discussed in more detail below).

The single most important disease-causing substance to avoid is tobacco. Ideally, one should never start smoking. If started, one should stop. It appears that stopping smoking, even after age 70, is associated with improved health. Even cutting down is associated with less respiratory infection and decreased mortality rates. The effect size of nonsmoking or low tobacco intake ranges from 1.2 to 4.5.6 Alcohol is often considered unhealthy, but there appears to be a dose effect, with moderate consumption (1-2 drinks 3-4 days/wk) being associated with reduced mortality and higher consumption levels having adverse consequences.8,9

Sleep appears to be important in optimal aging but while there is a lot of evidence about the adverse effects of sleep deprivation and sleep disorders causing a host of problems, there are limited data about optimizing sleep as a means for achieving a more successful aging experience. We know there are a number of normal changes in sleep architecture in elderly persons, including a reduction in slow-wave sleep, less REM sleep, and more time spent in Stage 1, resulting in less sleep efficacy. What is most interesting about these changes is that they may be related to hyperactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The result of this hyperactivity is excess glucocorticoid production, and glucocorticoids are toxic to the hippocampus itself.10 This change is also true of depression and may relate to the reasons why elderly individuals undergo some changes in cognitive function. Because sleep appears to be important in memory consolidation, it would seem likely that getting enough sleep would be an important component of optimal aging.

Preventive medicine interventions have been subjected to greater evidence-based scrutiny. Unfortunately, there is little evidence about the role of most prevention efforts after age 75. However, it is likely that those older people who are aging optimally could benefit from most interventions, as active life expectancy is long. For instance, the average life expectancy at age 80 is 8.5 years for both genders. There are numerous controversies, however. For instance, there is little evidence that treatment of hyperlipidemia with statins is beneficial in those over age 70 with no risk factors. The only randomized controlled trial, The PROspective Study of Pravastatin in the Elderly at Risk (PROSPER) study, showed no benefit in cardiovascular mortality reduction and an increased risk of cancer with treatment.11 The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American College of Physicians advise against screening for lipid disorders after age 75. Recommendations regarding the use of prophylactic aspirin are also controversial. A recent meta-analysis found that myocardial infarctions were reduced in men (odds ratio [OR], 0.86, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78-0.94) and ischemic strokes were reduced in women (OR, 0.83, 95% CI, 0.70-0.97). However, the risk of bleeding was increased in both genders (OR, 1.72 [95% CI, 1.35-2.20] and 1.68, [95% CI 1.13-2.52], for men and women, respectively.12 Clearly, the optimally aging person will want to consider the risk and benefits in deciding whether to take aspirin for cardiovascular prophylaxis.

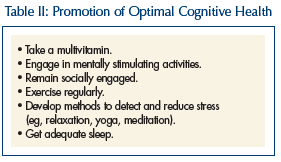

Adequate cognitive functioning is central to the concept of optimal aging (Table II). Much research is underway to better define the threat to cognitive functioning due to various diseases and life experiences. Less attention has been paid to ways to better maintain “brain power.” The genetic contribution to cognitive performance ranges from 30% to 80%.13 Higher levels of education and continued learning efforts are positively associated with maintenance of cognitive performance. It is unknown whether this is due to greater reserve capacity, or whether more intellectual stimulation maintains the functioning of neurons directly.14

Adequate cognitive functioning is central to the concept of optimal aging (Table II). Much research is underway to better define the threat to cognitive functioning due to various diseases and life experiences. Less attention has been paid to ways to better maintain “brain power.” The genetic contribution to cognitive performance ranges from 30% to 80%.13 Higher levels of education and continued learning efforts are positively associated with maintenance of cognitive performance. It is unknown whether this is due to greater reserve capacity, or whether more intellectual stimulation maintains the functioning of neurons directly.14

Oxidative stress has been implicated in many diseases that affect cognitive functioning, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. Prospective observational studies using vitamin E, vitamin C, ginkgo biloba, omega-3 fatty acid, and alpha lipoic acid have been conducted, but results have been conflicting.15 In addition, a recent meta-analysis of vitamin E supplements has shown an increase in all-cause mortality. Until long-term prospective trials have been completed, the use of a regular multivitamin containing vitamins C and E, folic acid, and B12, as well as having a diet high fruits and vegetables and in natural omega-3 fatty acids, seems the wisest choice.16 In addition, with the growing evidence of links between cerebral vascular disease and dementia (both vascular and Alzheimer’s disease), the principles involved in heart disease prevention (especially exercise) should be seen as also leading to dementia prevention and maintenance of cognitive performance.

Two other factors relate to cognitive decline and are potentially under the control of the person interested in optimal aging: stress and depression. The stress response is a potentially life-saving defense mechanism (“fight or flight”). However, many persons are subject to long periods of chronic, low-level stress. The brain responds to such situations with increased levels of serum cortisol, due to activation of the HPA axis. Higher cortisol levels, as in seen with Cushing’s disease or long-term pharmacologic use, have been associated with osteoporosis, diabetes, vascular disease, and accelerated brain aging and dementia.14 If possible, the best approach is to eliminate or escape from the stressful environment. Stress reduction techniques such as regular exercise, breathing exercises, tai chi, yoga, and meditation can all play a role in the reduction of chronic stress if it cannot be avoided.

Depression is known as a risk factor for the development of dementia.17 It too is associated with chronic elevations of serum cortisol. There is also evidence that depression is associated with structural brain changes, including loss of neurons in the hippocampus.18 Treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medications has been shown in animal studies to stimulate neuronal regeneration in the hippocampus. Exercise also has been shown to lead to hippocampal regeneration.

Exercise has been shown to be an effective antidepressant.19 A recent review of the role of exercise in depression management concluded that there is evidence of adult neurogenesis and an antidepressant effect.20 Persons with high degrees of social engagement experience less depression. There have been few studies on preventing depression in healthy individuals, but there is evidence in those with chronic health conditions that a program of instruction on body-mind relations, relaxation techniques, cognitive restructuring, problem solving, communication, and behavioral management of insomnia, exercise, and nutrition led to less depression.21 (See more on exercise below.)

PSYCHOSOCIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO OPTIMAL AGING

The research on psychological and social measures that contribute to optimal aging is less extensive than that for the biological realm. Perhaps that is because so much of the healthcare dollar is directed to medical illnesses and their treatment. It is also difficult to separate those factors that are psychological from those that are social. For instance, is loneliness a psychological issue (the emotional state of feeling lonely) or a social one (the absence of close, meaningful relationships)? As with the research in the biomedical arena, much that has been written in this area is directed toward identifying factors that contribute to disease or frailty, and in viewing those factors, how their opposite state may contribute to a healthier aging process. Hence, depression, loneliness,22 and economic deprivation are seen as risk factors for decline. It is intuitively sensible to think that happiness, a vibrant social life, and economic prosperity then would contribute to healthy aging. Yet, many studies have not addressed the question in that manner.

Unfortunately, there has been a long-held negative view of aging by both professionals and the public. In a survey of 400 older adults (mean age, 76 yr), Sarkisian et al23 found that more than 50% of subjects felt it was an expected part of aging to become depressed, more dependent, have less ability to have sex, and have less energy. The older the person, the lower the expectations. Not surprisingly, having low expectations was associated with not believing it was important to seek healthcare. Conversely, Almeida et al,24 in a study of over 600 Australian men in their 80s, found that 75% underwent “successful aging” (defined as an Mini-Mental State Examination score over 24 and a Geriatric Depression Scale score below 5). The strongest associations with the positive outcome were high school or college education and nonvigorous physical activity. Interestingly, marital status, smoking and alcohol use, weekly consumption of meat or fish, and medical problems of hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infarction, and stroke were not associated with mental health outcomes in this group. This study may indicate that many of the most feared risk factors in younger age may be of less importance in those over age 80. It adds to other research that indicates keeping mentally active provides a protective effect against cognitive decline and depression.25

Indeed, there is evidence that old age has a softening effect on many, causing elderly individuals to be more accepting of others and less likely to act in judgmental ways. That may be related to age-related changes in emotional regulation that has been seen over the course of the lifespan.26 Such a change would seem to be an advantage if it would make the adjustments needed to adapt to the frequent expected and normal changes of age more likely. An example of such an adjustment, which surprised me as a geriatrician, was seen in the book Tuesdays with Morrie,27 the story of an older man with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis who discovers that an important aspect of his adjustment to the disease is an acceptance of being dependent, a state which geriatricians usually try to help patients avoid. It could be argued that his successful adaptation to near total dependency was the true sign of optimal aging. Ram Dass,28 in his telling of living through a stroke, provides a similar account of unexpected growth and development of a greater sense of self through this experience.

SOCIAL CONTRIBUTORS TO OPTIMAL AGING

In the last two decades there has been a growing awareness of the importance of social support in the lives of older persons, especially in relation to development of disease and management of their sequelae. Social support was shown long ago to be beneficial to health and act as a buffer against the distresses caused by disease.29 The influence of social support has been studied in specific diseases, such as osteoarthritis. In one study, greater social companionship was associated with higher physical functioning, general health, mental health, and vitality. Being satisfied with the problem-solving support received was associated with better physical functioning, mental health, social functioning, and vitality.30

Social activities take many forms. Persons may be involved in social engagements such as parties, visiting friends, and participation in group activities. Others may be involved in productive activities, such as work or volunteering in public service. Many older persons become more politically active after retirement. Some resume schooling, and many colleges and universities now offer educational programs specifically for older persons. And of course, leisure and physical activities are commonly pursued. All of these involve stimulation and maintenance of physical, mental, and functional reserves.

In addition, a large component of social activities of older individuals relates to caregiving. The majority of healthcare service is provided by the family (“informal care”), with only a small component provided by formal care services. The literature on health effects of caregiving is mixed. It appears that the potential health benefits of caregiving relate more to the perception of burden on the part of the caregiver, rather than an objective external measure of how much work is required.31

Speaking of social activities and support as if they were something separate from the other domains is, of course, artificial. Everything is connected to everything. There is growing evidence that social support directly affects biological functions. Social integration has been found to be associated with decreased levels of C-reactive protein, a risk factor for heart disease. This finding was independent of multiple other risk factors, such as smoking, socioeconomic status, and depression.32 Mendes de Leon et al33 found that involvement in social activities with family and friends reduces decline in activities of daily living (ADL) and enhances recovery of ADL function. Others have found that productive work and social interactions have independent protective effects of functional health.34

It makes intuitive sense that social engagement would have beneficial effects on mental health, and this relationship has been borne out in a large number of studies.35 Playing bridge, visiting friends, and attending social gatherings have all been associated with higher levels of cognitive functioning.36 Being involved in productive and helping activities has been associated with lower levels of depression and declines in both mood and somatic symptoms. Large-scale studies, such as the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), are examining the role of relationships in healthy aging.37 This research will provide healthcare providers and public health policymakers with a scientific base of information for advising older people about positive social and intimate relationships, as well as designing health programs to promote these relationships.

Finally, there is substantial evidence that social engagement and activity has positive effects of survival. Church attendance, outings to sports events or other social functions, and other leisure activities have been shown to have mortality reduction effects, even when controlling for age and other risk factors. Work-related activities, such as volunteering and even paid work, have shown similar benefits.38 It is clear that social engagement and activities promote health, reduces disability, and lowers mortality risk.

FUNCTIONAL CONTRIBUTORS TO OPTIMAL AGING

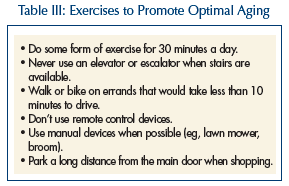

The single most important health-promoting activity a person can engage in is exercise. Physical activity of any type is a form of exercise, even doing one’s daily activities, such as bathing and getting out of bed (Table III). If more people are to achieve optimal aging, expanding the number of people engaging in regular exercise will have an even greater effect than getting people to stop smoking. This is because only about 25% of the older population smokes, but 70% of the population do not engage in regular exercise.39

The single most important health-promoting activity a person can engage in is exercise. Physical activity of any type is a form of exercise, even doing one’s daily activities, such as bathing and getting out of bed (Table III). If more people are to achieve optimal aging, expanding the number of people engaging in regular exercise will have an even greater effect than getting people to stop smoking. This is because only about 25% of the older population smokes, but 70% of the population do not engage in regular exercise.39

In a longitudinal study of aging, people over age 85 were followed for eight years. Exercise was associated with higher levels of positive affect and a greater sense of meaning in life, fewer limitations on instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), and greater longevity.40 Moderate levels of activity have been associated with fewer hip fractures in women.41 Higher levels of activity may protect against the development of Parkinson’s disease.42 Physical activity is associated with a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality.43 Regular physical activity reduces the risk of functional dependency, one of the most commonly reported fears of older people.44 Regular physical activity has been shown to be beneficial in preventing or helpful in managing nearly every major cause of illness in older people, including cardiovascular disease, stroke, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, obesity, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, and depression. In that way, exercise is unique in that it is both a preventive intervention and a treatment.

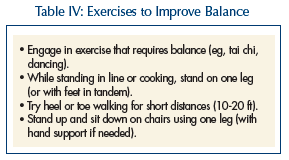

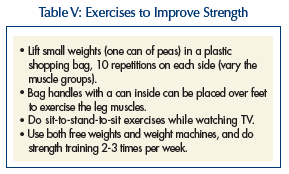

The activities that one should maintain (or adopt if not using) are relatively straightforward. If one is living a sedentary life, one should adopt a more active one. Exercise should encompass four major areas: aerobic capacity, balance (Table IV), flexibility, and strength (Table V). Simple changes such as walking rather than using the car for short distances, taking the stairs rather than elevators, standing on one leg when cooking, occasionally walking in tandem, on heels, and on toes can be helpful. In that optimal aging is a goal for those with chronic conditions, then interventions should be targeted to the deficits of the person. If rising from a chair is difficult, hip-strengthening exercises are advised. If one tires performing ADLs, endurance conditioning exercises would be helpful. If there are difficulties bathing and reaching the back, flexibility exercises should be used. Maria Fiatarone Singh39 makes a number of simple recommendations that contribute to optimal aging.

The activities that one should maintain (or adopt if not using) are relatively straightforward. If one is living a sedentary life, one should adopt a more active one. Exercise should encompass four major areas: aerobic capacity, balance (Table IV), flexibility, and strength (Table V). Simple changes such as walking rather than using the car for short distances, taking the stairs rather than elevators, standing on one leg when cooking, occasionally walking in tandem, on heels, and on toes can be helpful. In that optimal aging is a goal for those with chronic conditions, then interventions should be targeted to the deficits of the person. If rising from a chair is difficult, hip-strengthening exercises are advised. If one tires performing ADLs, endurance conditioning exercises would be helpful. If there are difficulties bathing and reaching the back, flexibility exercises should be used. Maria Fiatarone Singh39 makes a number of simple recommendations that contribute to optimal aging.

As it appears that 50% of the factors that influence health are due to behaviors such as drinking and eating habits, smoking, and exercise patterns, clinicians should be skilled at helping people to change those behaviors.45 As the number of baby boomers rise, it is expected that there will be increasing demand for that type of advice. Yet most psychological programs that have tried to modify health behaviors have been disappointing.46 In addition, many people make significant changes in unhealthy behaviors without the assistance of a healthcare provider. For example, most people who quit smoking do it on their own, rather than through a formal smoking cessation program.46

As it appears that 50% of the factors that influence health are due to behaviors such as drinking and eating habits, smoking, and exercise patterns, clinicians should be skilled at helping people to change those behaviors.45 As the number of baby boomers rise, it is expected that there will be increasing demand for that type of advice. Yet most psychological programs that have tried to modify health behaviors have been disappointing.46 In addition, many people make significant changes in unhealthy behaviors without the assistance of a healthcare provider. For example, most people who quit smoking do it on their own, rather than through a formal smoking cessation program.46

Some notable programs have been dedicated to changing health behaviors. The largest attempt to change health behaviors was the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT).47 This was a 10-year-long program, begun in 1971, that screened over 350,000 high-risk men, finally enrolling more than 7000 subjects. Two groups were randomized to receive either the MRFIT intervention or usual care. The subjects were highly motivated and well informed. They expressed willingness to change their diet, stop smoking, and visit the clinic once or twice a week for 6-8 years. The results were not encouraging. After 6 years, 65% of the participants were still smoking, few had changed their diets, and only half had their blood pressure under control. Men in the control group had similar results.47 Other community intervention programs have had similar results.48,49 On the other hand, other programs have shown benefits. Two large randomized trials of a health promotion program for retirees showed improvements in health and a lowering of healthcare costs.50,51 This was accomplished solely through mailed risk assessments and recommendations.

SOCIETAL APPROACHES TO OPTIMAL AGING

There are many ways that society could foster optimal aging activities. From promoting healthy behaviors through health plans, to engineering buildings to promote use of stairs, the options are almost limitless. Unfortunately, short-term concerns of cost considerations often impede businesses and government from taking such an approach.

Health education is one approach that has received a good deal of attention from organizations52 and from health maintenance organizations.53 Lorig et al54 conducted training sessions in self-management skills for persons with chronic illnesses. These trainings, led by trained laypersons with chronic conditions, resulted in lower rates of emergency room and outpatient use while increasing patient self-efficacy. A review of multiple healthcare systems that have now instituted chronic care programs was published in 2002.55 One can also change the way patients with chronic conditions are scheduled for office visits to improve self-care abilities.56 By better supporting patients with chronic conditions, health plans are able to promote optimal aging.57

Another way that optimal aging can be promoted by society is through information technology. Access to valid information on healthy life choices, information on diagnosis and treatment, and availability of qualified providers of all types enables persons interested in optimal aging to make more informed choices. Kemper and Metteler58 have promoted the concept of “Information Therapy”—providing the right information to the right patient at the right time. Such information can be built to be delivered in an almost automatic fashion. For instance, if a physician were to diagnose osteoarthritis in a patient, as soon as the diagnosis is coded into the electronic health record (EHR), an e-mail with links to exercises recommended could be sent to the patient’s computer. Similarly, in hospitals, doctors could have patient instructions sent by e-mail to the patient (or his/her family caregiver) at discharge. Electronic health records are critical to the proper use of information technology to promote optimal aging. Health systems that have instituted EHRs have shown improvements in preventive interventions.59

Community Programs

Interventions that have been promulgated by the community have shown some success. In the North Karelia region of Finland, an intervention was developed that focused on structural changes in the community, not just education. Local producers of meats and dairy products were convinced to reduce fat in their products; schools were used as community discussion centers. During a seven-year intervention, coronary heart deaths dropped more than 60%.60 Perhaps it will be shown that for large numbers of persons to achieve optimal aging, a systems approach (rather than an individual one) will be needed.

More social programs to promote healthy aging are badly needed.61 Senior centers often conduct wellness programs, but many are on limited budgets. Current programs could be expanded to include the full array of educational interventions covering biological, psychological, social, and functional components. This would reach a significant portion of the aging population, as more older Americans use senior centers than any other community service targeting the older population. Public education programs through schools, community colleges, and universities could be expanded. Outreach programs could be developed in places frequented by older persons, such as shopping malls and places of worship. Unfortunately, funding for such programs has been level or even decreasing in recent years. The Social Services Block Grant program is only 30% of what it was in 1980.62 Unfortunately, these types of programs tend to be more available in urban areas, with elderly persons in rural areas having less access to needed resources.

Public policy has a tremendous influence on promoting health in the community, especially for elders, where nearly all of the funding comes from public sources.63 Medicare has expanded its focus on disease prevention, especially in the areas of cancer and osteoporosis screening, medical nutrition therapy (for certain conditions), and immunizations. However, an older study found that beneficiaries received recommended care less than two-thirds of the time.64 African Americans were substantially less likely to receive necessary care. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention launched the Healthy Aging Project, among others.65,66 The National Institute on Aging has a number of resources dedicated to healthy aging.67,68

Age-Friendly Design An area that is receiving increasing attention regarding the promotion of healthy aging is urban design, so-called “age-friendly design.” An important consideration in convincing local, state, and national governments as to the value of such design is that the changes made benefit persons of all ages. These changes encompass creating safe and secure pedestrian environments, promoting mobility options for seniors, supporting the construction of recreation facilities, parks, and trails, and encouraging housing options.69 Many programs have sought out older people to serve on planning councils, offering not only the chance to have plans reviewed by the end users, but also creating more opportunities for older people to engage in meaningful mentally stimulating activities. This type of design is both more functional and more aesthetic than the usual urban construction. Wider sidewalks with contrasting colored concrete encourages walking and makes it safer for those with visual impairment. Lining streets with trees, having sitting areas, and limiting the use of large blank walls along the walkway encourages physical activity and expands business opportunities. Narrower streets with both visual and audio crossing encourage exercise. Streets themselves are made safer and more user-friendly by having large-print signs, dedicated left-turn signals and lanes, and better setbacks of buildings to promote clear visualization of traffic control devices.70,71

IMPLICATIONS FOR OPTIMAL AGING

There is already evidence that much of the older population is aging in a more optimal fashion. Death rates for heart disease and stroke are declining. Rates of disability are falling as well.72 The number of older people is ever increasing. What if even more people adopted the practices that would lead to optimal aging? One implication is that the number of people with chronic conditions is not likely to decline. Using the principles of optimal aging (as opposed to “successful aging,” which stresses the absence of chronic conditions), it would seem likely that such persons would live longer and be less disabled by their conditions. However, it is likely that they will also continue to be heavy users of healthcare services. Simply due to the rising number of people entering old age, healthcare expenditures may increase sixfold.73 However, if people make changes toward optimal aging, it is likely that expenditures may not increase as much as they have in the past, due to the compression of morbidity into the last years of life.74 Prevention of health problems is one of the few ways in which society can avoid huge increases in healthcare spending.75 The promotion of optimal aging is beneficial not only to the person practicing the principles, but to our entire society as well.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships. Research reported in this article is supported by the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation.

Resources for Optimal Aging