Common Sleep Problems Affecting Older Adults

WHAT IS SLEEP?

Sleep is normally composed of two separate states: rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM (NREM) sleep. Non-REM is divided into four sleep stages on a “depth of sleep” continuum. These stages cycle throughout the night from light sleep (stage 1) to deep sleep (stages 3 and 4), and back again about every 90 minutes. Deep sleep in stages 3 and 4 appears to be when physiological restoration of the body occurs.1 Periods of REM sleep occur at the beginning of each new 90-minute cycle. REM sleep (also called “paradoxical sleep” because brain activity resembles that of wakefulness) is when most vivid dreaming occurs. During REM sleep, the body is essentially paralyzed, a phenomenon known as REM atonia. Research suggests REM sleep plays a role in memory consolidation and overall health.2

HOW DOES SLEEP CHANGE WITH AGE?

Nighttime Sleep

Sleep patterns and sleep quality change throughout the lifespan.3 Normal sleep changes are expected and predictable as people enter later adulthood. The most notable change in older adults’ sleep architecture is a decrease in the amount of deep sleep (stages 3 and 4). In addition, the percentage of REM sleep decreases slightly in older age. Older adults’ sleep is typically more fragmented; that is, sleep is more often interrupted by wakefulness. It is important to note that among the healthiest older persons, sleep quality is generally maintained. Among the general population of older adults, however, there are likely multiple causes of sleep fragmentation, including sleep disorders (eg, sleep apnea), behavioral and lifestyle factors (eg, extended time in bed), and medical conditions (eg, arthritis). One common misconception is that older persons need significantly less nighttime sleep than their younger counterparts. In fact, the change in sleep need across adulthood is minimal; however, many factors impact the ability of older adults to obtain sufficient sleep at night.

Daytime Sleep

Older adults are more likely to report daytime sleepiness and to nap as compared to younger adults. Studies estimate that about one-quarter of older adults nap regularly and 13-20% report significant daytime sleepiness.4 For many older adults, daytime sleepiness negatively impacts quality of life. It appears that much daytime sleepiness and daytime sleeping is the result of insufficient nighttime sleep. In addition, daytime napping (particularly naps over 1 hour in length) can lead to a decrease in the amount of sleep an individual is able to get at night.

Circadian Rhythms

The body’s internal clock plays an important role in regulating sleep/wake cycles. Circadian rhythms change over the lifespan, and older adults often find their sleep affected by these changes.5,6 Typically, the timing of sleep shifts to an earlier time (ie, advances) from adulthood to old age. For some individuals, this change in the timing of sleep is benign; however, for others this change is problematic (see advanced sleep phase syndrome, below).

SLEEP DISORDERS

As described above, some changes in sleep architecture and sleep timing are expected consequences of normal aging; however, older people do not need significantly less sleep than younger people. The sleep problems of older adults are typically the result of sleep disorders, including sleep disordered breathing, periodic limb movement disorder, restless legs syndrome and advanced sleep phase syndrome, or to the impact of medical conditions, medications, and psychiatric disorders on sleep. In addition, changes in lifestyle can impact sleep in older people and can lead to complaints of insomnia.

Insomnia

Insomnia is a complaint of insufficient or non-restorative sleep, characterized by difficulty falling asleep, repeated awakening, inadequate total sleep time, or poor sleep quality, which is accompanied by poor daytime functioning.7 Insomnia can manifest as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, or trouble with early morning awakenings. Insomnia can last a few days (transient insomnia), a few weeks (short-term insomnia), or can go on for more than a month (chronic insomnia). The type and duration of insomnia can help determine the approach to treatment.

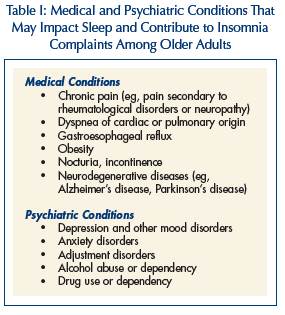

Up to 40% of those over age 60 complain of disturbed sleep, with over 20% reporting severe insomnia. Women generally report more sleep problems than men, and Caucasians report more sleep problems than African Americans.8,9 True primary insomnia (ie, insomnia that is not attributable to a medical or environmental cause) is fairly rare among older adults, accounting for only 5-20% of cases.10 The majority of insomnia complaints among older persons are secondary to or comorbid with some other condition that impacts sleep quality. These conditions can include medical conditions, neurological disorders, primary sleep disorders, substance abuse, prescription medications, or psychiatric conditions. Among older adults, nocturia is a common complaint that contributes to sleep disturbance. About 30% of men over age 55 and 28% of women over age 60 get up at least twice per night to urinate.11,12 Table I lists some medical and psychiatric conditions that commonly impact sleep and can lead to insomnia complaints among older adults.

Up to 40% of those over age 60 complain of disturbed sleep, with over 20% reporting severe insomnia. Women generally report more sleep problems than men, and Caucasians report more sleep problems than African Americans.8,9 True primary insomnia (ie, insomnia that is not attributable to a medical or environmental cause) is fairly rare among older adults, accounting for only 5-20% of cases.10 The majority of insomnia complaints among older persons are secondary to or comorbid with some other condition that impacts sleep quality. These conditions can include medical conditions, neurological disorders, primary sleep disorders, substance abuse, prescription medications, or psychiatric conditions. Among older adults, nocturia is a common complaint that contributes to sleep disturbance. About 30% of men over age 55 and 28% of women over age 60 get up at least twice per night to urinate.11,12 Table I lists some medical and psychiatric conditions that commonly impact sleep and can lead to insomnia complaints among older adults.

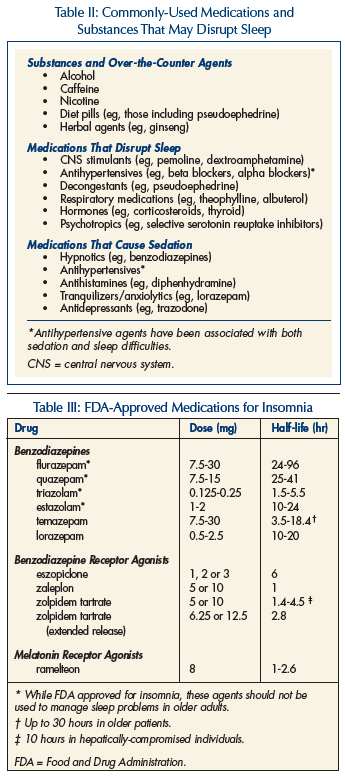

Another important consideration in treating insomnia among older adults is that many prescribed and over-the-counter medications impact sleep. Substances such as alcohol, caffeine, and nicotine also impact sleep, and in general, should be avoided in the evening hours. Table II lists medications and substances that can adversely impact sleep either by causing daytime sedation or by directly disrupting nighttime sleep.

Diagnosis of insomnia includes an evaluation of sleep habits and patterns as well as a medical and psychiatric history. Assessment should include not only nighttime symptoms, but also daytime functioning, including cognitions and behaviors that could affect nighttime insomnia. The diagnostic process might include completing a daily sleep diary in addition to a diagnostic interview. Polysomnography (PSG), a comprehensive overnight recording of sleep, is generally not indicated in the evaluation of insomnia.13

Diagnosis of insomnia includes an evaluation of sleep habits and patterns as well as a medical and psychiatric history. Assessment should include not only nighttime symptoms, but also daytime functioning, including cognitions and behaviors that could affect nighttime insomnia. The diagnostic process might include completing a daily sleep diary in addition to a diagnostic interview. Polysomnography (PSG), a comprehensive overnight recording of sleep, is generally not indicated in the evaluation of insomnia.13

Treatment. Because complaints of insomnia are so often comorbid with other conditions in older adults, these conditions must be considered in the approach to treatment. Recent research shows that it is not always necessary or desirable to delay treatment of insomnia to address suspected underlying causes first; however, it is critical to consider medical conditions and psychiatric disorders in tailoring interventions to an individual patient. For example, in an older adult at high risk for falls, pharmacotherapy may be contraindicated, or for an older adult with limited mobility, behavioral recommendations may need to be adapted. Treatment of insomnia complaints can be pharmacological and/or nonpharmacological.

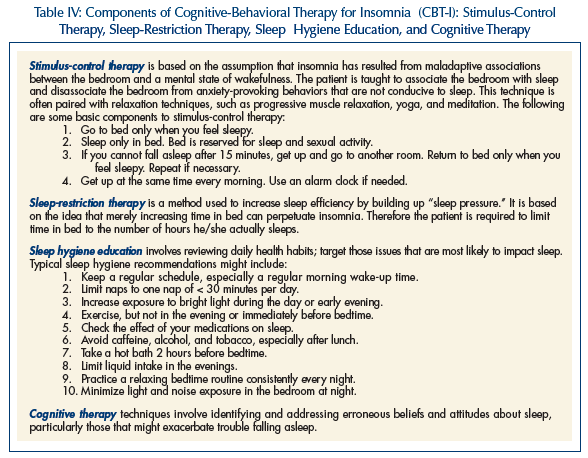

Pharmacological treatments for insomnia include medications that are FDA-approved for the treatment of sleep problems (Table III) and other medications (eg, antidepressants) that are used “off-label.” In considering the appropriateness of pharmacotherapy for older adults, one must consider the risk profile of the medication (including risks of drug interactions), the degree of severity and type of sleep problem, the goals of treatment, and the overall health status of the patients. Recent findings suggest that newer hypnotic agents (benzodiazepine receptor agonists and melatonin receptor agonists) have fewer safety concerns than older agents, and may be more appropriate for longer-term use.14 These medications decrease the time it takes to fall asleep, and some decrease the number of awakenings during the night. Of greatest concern is the use of these agents in frail older adults. Multiple studies have found an increased risk of falls among frail older adults taking benzodiazepines and other psychotropic medications.15-18 In addition, research shows that sleep problems are commonly caused or exacerbated by lifestyle/behavioral factors, which must be addressed for long-term improvements in sleep to be achieved.

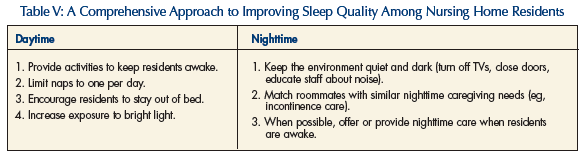

Antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihistamines, and muscle relaxants are sometimes used to treat sleep problems because of their sedating side effects. It is important to consider that there are no controlled studies demonstrating that these medications are safe or effective in the treatment of insomnia. In the absence of a primary indication for the use of these medications (for example, it may be appropriate to use a sedating antidepressant to address the sleep complaint of a person with depression), they are not recommended in the treatment of sleep problems. Several randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews show that older adults with insomnia benefit greatly from nonpharmacological interventions on sleep.19-21 There is a growing body of evidence for the use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which is a multi-component approach designed to address multiple sleep issues concurrently (Table IV).

Sleep Disordered Breathing

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is a condition characterized by periodic impairment of respiration during sleep. Apneas are complete cessations of respiration. Partial decreases in respiration are known as hypopneas. Respiratory events can be caused by obstruction of the upper airway (obstructive apnea), loss of ventilatory effort (central apnea), or a combination of the two. Sleep disordered breathing is typically diagnosed with PSG, in which airflow is recorded, usually in combination with respiratory effort, blood oxygen saturation, and other parameters. A diagnosis of SDB is made when 15 or more respiratory events (apneas plus hypopneas) occur per hour of sleep.

Sleep disordered breathing affects persons of all ages, and the prevalence increases with age. SDB is especially nefarious not only because of its association with morbidity and mortality, but also because signs of SDB are often associated with aging. Snoring and daytime sleepiness are the most common presenting symptoms of patients with SDB. While SDB is more common in younger men than younger women, this gender difference decreases greatly as a result of an increase in prevalence of SDB among women as they age. Rates of SDB are also higher in postmenopausal women than premenopausal women, higher in African Americans than in Caucasians, and higher in persons with hypertension as compared to those without hypertension.20 Prevalence rates vary, but are likely around 20% for adults over age 65.22,23

Treatment. The treatment of choice for SDB is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This treatment involves applying positive pressure to the airway, which acts as a splint to prevent airway collapse during sleep. This is achieved by having the patient wear a mask over his or her nose during sleep, which is connected via a hose to a machine that generates positive air pressure. Continuous positive airway pressure is highly effective in reducing the number of respiratory events. CPAP is not curative, however, and patients must use the CPAP machine indefinitely.

Other treatment options include the use of dental devices that reposition the jaw, weight loss, and surgery. Dental devices may be effective in alleviating SDB when obstruction occurs high in the airway. These devices are generally considered an alterative to CPAP rather than first-line therapy. Dental devices may reduce the severity of SDB among older adults with medical comorbidities.24 Weight loss is also sometimes suggested since fatty tissues in the neck can reduce the size of the airway and increase the likelihood of obstruction. While being overweight can contribute to SDB, and overweight patients should be advised to lose weight as part of treatment, weight loss alone is rarely sufficient to ameliorate SDB. Surgical procedures have been developed and are sometimes used to treat SDB. Interventions involve modifying the pharyngeal anatomy or bypassing the pharynx, and are curative for many patients. The risks associated with surgical procedures among older adults must be carefully considered.

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder and Restless Legs Syndrome

Periodic limb movements (PLMs) involve repetitive, highly stereotyped movements during sleep, and are common among older patients. Standard criteria define a PLM event as a series of four or more limb movements lasting 0.5 to 5 seconds with an inter-movement interval of 4 to 90 seconds. If PLMs occur more than 15 times per hour, the condition is considered pathologic.7 Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) occurs when PLMs are associated with complaints of insomnia and/or excessive sleepiness.7 Periodic limb movement disorder is diagnosed using PSG, although less cumbersome and less expensive methods are currently being developed. Sleep disorders centers report that patients with PLMD are often significantly older than patients without PLMD, and the disorder becomes more severe with age. Although prevalence data are not available using the criteria of 15 events per hour of sleep, a study using older diagnostic criteria (5 events/hr) found that the prevalence of PLMD in community-dwelling older adults was 45%, with no gender difference.25 A second study found that the number of PLM episodes increases with age, suggesting an increase in the prevalence of the disorder across the lifespan.26

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is closely related to PLMD. It is characterized by an irresistible urge to move the legs. These feelings typically occur at rest and improve with movement. It is common for the feelings to intensify later in the day and become problematic while the patient is in bed trying to fall sleep. The feelings in the legs are sometimes described as “restlessness,” “tingling,” or “itching.” RLS is diagnosed based on history. Periodic limb movement disorder and RLS frequently coexist.

Treatment. Anecdotal evidence suggests that PLMD and RLS can be treated with hot or cold presses, moderate exercise, or other therapeutic techniques; however, only one randomized study has examined the effectiveness of a nonpharmacological treatment for PLMD.27 Pharmacotherapy has the most supporting evidence in the management of PLMD and RLS. Ropinirole is the only FDA-approved agent for the treatment of RLS. Dopaminergic agents are the primary treatments for PLMD and RLS. Depending on the severity of the symptoms, drugs such as carbidopa/levodopa may be used on an “as-needed” basis. Benzodiazepines and opioids, though effective in reducing the sleep disruption associated with PLMS, involve higher risk for older adults and are not typically considered first-line therapies. In addition, RLS can be associated with low levels of ferritin in the blood, and iron-replacement therapy is indicated in RLS patients whose ferritin levels are less than 45-50μg/L.

Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome

As mentioned above, advanced sleep phase syndrome (ASPS) is characterized by a sleep phase shifted earlier than normal or desired. Patients become sleepy earlier than desired (eg, 7:00-8:00 pm), and wake up earlier than desired (eg, 3:00-4:00 am). Although some older people try to counteract this by staying up until 10:00 or 11:00 pm, they often still awaken early in the morning due to internally-driven circadian rhythms. The resulting lack of sleep can contribute to sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness. When the change in sleep timing leads to daytime difficulties for an older person, ASPS is diagnosed.

Advanced sleep phase syndrome has a prevalence of about 1% in middle-aged and older adults, and the rate increases with age. Men and women are equally affected.1 Typically, ASPS begins in middle adulthood, and, if left untreated, remains a chronic condition. Diagnosis typically involves the patient keeping a sleep diary and/or wearing a wrist actigraph for at least a week. It is important to differentiate between ASPS and insomnia in older adults, as they present with similar symptoms. Correctly identifying the condition will avoid ineffective or inappropriate treatments.

Treatment. It is important to treat ASPS comprehensively, since contributing factors often include both circadian rhythm changes and maladaptive behaviors. Bright light therapy can be used to resynchronize the sleep-wake cycle to more appropriate times. To achieve the intensity levels required, outdoor sunlight or light from commercial light boxes can be used. Typically, a patient is exposed to light with intensity between 2500 and 10,000 for at least 30 minutes in the evening hours for 2-3 weeks.28 As ASPS can be complicated by behavioral factors, sleep hygiene issues should also be addressed (Table IV).

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS IN THE NURSING HOME SETTING

In general, the same factors that impact sleep among older adults in the community impact the sleep of residents of nursing homes. In addition to these factors, however, the institutional environment can add to disrupted sleep patterns. Particular concerns are daytime physical inactivity, a paucity of social interactions, low levels of indoor light with residents seldom taken outdoors, and residents spending considerable amounts of time in their own rooms and in bed during the daytime hours. During the night, the environment is not typically conducive to restorative, restful sleep. Research shows that nursing homes are noisy and lights are left on all night, and patient room doors are left open, allowing noise and light from outside the room to disrupt sleep. Improving sleep quality at night should be approached primarily by behavioral means, as there are no data to support the use of sedative-hypnotic medications for sleep in the nursing home setting. Table V lists recommendations for improving sleep/wake patterns among nursing home residents. Strategies must include both reducing daytime sleeping and creating an environment that is conducive to consolidated sleep at night.

SUMMARY

Sleep problems are common among older adults, and multiple factors impact the ability of older people to obtain adequate nighttime sleep. Sleep disordered breathing, periodic limb movement disorder, restless legs syndrome, and medical/psychiatric disorders can all contribute to the high prevalence of sleep complaints among older persons. Treatment of sleep problems should focus on improving overall functioning and quality of life, and appropriate treatment should be available to older persons with sleep complaints.

Supported by UCLA Claude Pepper OAIC (AG-10415; PI: Reuben) Career Development Award (PI: Martin), VA Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 04-321-3, Alessi) and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center, Sepulveda.