Hospitalization of the Elderly

“The hospitalization, not the illness, may be the deciding factor in the functional ability of the frail, elderly at discharge”1

As the number of older adults increases, it is our duty to provide them with comprehensive care, namely in the acute setting. Vulnerable, frail individuals are at increased risk for worsening functional status and delirium, falls, medication toxicity, nosocomial infections, malnutrition, dehydration, immobilization, and decubitus ulcers while in the hospital.2 Elderly patients are susceptible to complications not directly related to the illness for which they are hospitalized. These complications begin immediately upon admission.3 Geriatric consultation teams and geriatric care unit models have been designed and studied over the years to improve patient functioning and prevent deleterious events in acutely ill older adults.4 This article will review the history of acute care of the elderly, discuss alternative methods of acute care, and examine functional decline, delirium, and transitions of care.

In the early 20th century during World War II, a geriatric unit was formed in Great Britain. Dr. Marjory Warren5 described the structural alterations made to a part of a hospital to improve the lighting, widen the doorways, and install handrails. On this unit, elderly patients with various conditions that included malnutrition, anemia, dementia, cerebral thrombosis, arthritis, chest disease, and neoplasms were cared for. Patients were transferred from the surgery and orthopedics services to this special unit. The importance of physiotherapy, social work, and an interdisciplinary team was clearly recognized. Dr. Warren wrote, “As the department gains experience, confidence and skill, it should be able to prevent a great number of the conditions which are so prevalent and so crippling amongst elderly persons today.”5 Her observations have withstood the test of time and are as relevant today as they were in 1935.

Geriatric Consultative Services

In 1979, Burley et al6 studied a geriatric consultative service for patients with incontinence and difficulty ambulating, in addition to multiple medical problems. These patients with “geriatric features” were more likely to be discharged to home, as opposed to another ward, which resulted in an overall decrease in length of stay.6 A randomized controlled Veterans Administration trial in the 1980s showed a trend toward greater improvement in functional status in patients evaluated by a geriatric consultative team. This study concluded that geriatric consultants, in order to show meaningful improvements, should offer direct care and services.7 Another study showed significantly greater improvement in mental status, a decrease in number of medications upon discharge, and lower short-term death rates when care was received from a geriatric consult service.8 In the mid-1990s, a randomized controlled trial compared a comprehensive geriatric assessment in the form of consultative versus usual care.9 There was no difference in functional status at 3 and 12 months or in 1-year survival; however, they concluded that the consultative service is only as good as the implementation of its recommendations.9,10 Frail, hospitalized elders may benefit more from comprehensive geriatric assessment and management in the form of continuous, rather than consultative, care.

Geriatric Units

Saunders et al11 describe the Geriatric Special-Care Unit (GSCU) at the University of Massachusetts that opened in 1980. Modifications were made to an existing unit, including communal dining areas with adaptive feeding equipment, call bells with long cords, and alarm signals on stairway exit doors. The major goals of the team were: to maintain or restore mobility and function; to prevent or relieve confusion and disorientation; to maintain the activities of daily living (ADLs); and to assess the patient’s resources and needs. Results showed that the patients on this unit had a shorter average length of stay than similar-aged patients on other units.11

Rubenstein et al12 randomized patients to a geriatric evaluation unit with follow-up in the geriatric clinic versus usual care. During the first year of follow-up, there was a lower mortality rate in the geriatric unit patients as compared to the control patients. A higher percentage of patients in the geriatric unit were discharged to their home, whereas more than twice as many in the control group were discharged to a nursing home. During the first year, fewer unit patients were re-hospitalized and used fewer long-term care services. Overall, functional status and mental status were better in the unit group. Cohen and colleagues13 conducted a randomized trial that showed significant reductions in functional decline with inpatient geriatric evaluation followed by outpatient follow-up and management.

Landefeld, Palmer and others14 conducted a randomized trial in which specific changes to the physical design of the unit including larger clocks and calendars, handrails, elevated toilet seats, and door levers, in addition to patient-centered care, discharge planning, and medical care review, improved ADL function and reduced the number of discharges to long-term care facilities. He called this program “Acute Care for Elders.” Geriatric assessment units, termed “the new technology of geriatrics” were becoming a promising and efficient method for delivering healthcare to elderly persons.15 Palmer et al16 further describes the Prehab Program of Patient Centered Care as a multifaceted intervention that integrates geriatric assessment into the optimal medical and nursing care of all patients. He describes this program to prevent functional decline on the Acute Care of the Elderly Unit (as Landefeld et al14 describes). This model of care is an inexpensive, interdisciplinary, collaborative approach focusing on changing the physical environment and targeting the processes of care. The environmental changes, similar to the Landefeld et al14 unit, include communal dining areas, calendars and larger clocks, lower beds with floor lighting, visually appealing and contrasting paint and wallpaper, elevated toilet seats, grab bars, and carpets in hallways and rooms. Other goals of this model include medication review, interdisciplinary team rounds, and early extensive discharge planning. The nursing staff is very focused on fluid and nutritional intake, helping patients ambulate throughout the day, avoiding restraints, and removing unnecessary catheters and intravenous lines. All members of the care team monitor patients for delirium and depression.

A randomized clinical trial of 661 elderly patients assigned to the Acute Care of Elders (ACE) unit versus usual care on a general medical unit showed that ADL function was improved at discharge in 34% of ACE patients, compared to 24% of the usual-care patients.17 Fewer patients on the ACE unit were discharged to a long-term care facility (as a new resident). Though not statistically significant, there was a trend toward shorter length of stay in the ACE unit group.

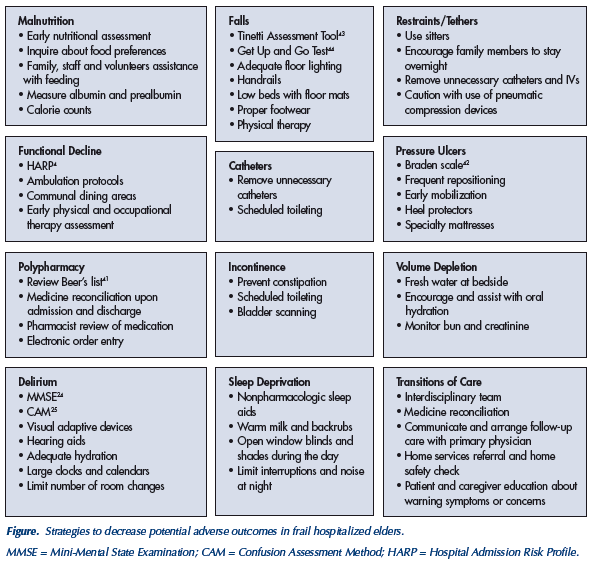

----Malnutrition - Early nutritional assessment - Inquire about food preferences - Family, staff and volunteers assistance with feeding - Measure albumin and prealbumin - Calorie counts

----Falls - Tinetti Assessment Tool43 - Get Up and Go Test44 - Adequate floor lighting - Handrails - Low beds with floor mats - Proper footwear - Physical therapy

----Restraints/Tethers - Use sitters - Encourage family members to stay overnight - Remove unnecessary catheters and IVs - Caution with use of pneumatic compression devices

----Functional Decline - HARP4 - Ambulation protocols - Communal dining areas - Early physical and occupational therapy assessment

----Catheters - Remove unnecessary catheters - Scheduled toileting

----Pressure Ulcers - Braden scale42 - Frequent repositioning - Early mobilization - Heel protectors - Specialty mattresses

----Polypharmacy - Review Beer’s list - Medicine reconciliation upon admission and discharge - Pharmacist review of medication - Electronic order entry

----Incontinence - Prevent constipation - Scheduled toileting - Bladder scanning

----Volume Depletion - Fresh water at beside - Encourage and assist with oral hydration - Monitor bun and creatinine

----Delirium - MMSE24 - CAM25 - Visual adaptive devices - Hearing aids - Adequate hydration - Large clocks and calendars

----Sleep Deprivation - Nonpharmacologic sleep aids - Warm milk and backrubs - Open window blinds and shades during the day - Limit interruptions and noise at night

----Transitions of Care - Interdisciplinary team - Medicine reconciliation - Communicate and arrange follow-up care with primary physician - Home services referral and home safety check - Patient and caregiver education about warning symptoms or concerns

Strategies to decrease potential adverse outcomes in frail hospitalized elders.

MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; CAM = Confusion Assessment Method; HARP = Hospital Admission Risk Profile.

A greater amount of resources and manpower are needed to care for frail older adults. Designing and constructing a special unit requires money and resources. A randomized trial of geriatric units conducted by Rubenstein et al12 showed lower direct costs, in that patients had less acute hospitalization and nursing home level of care as compared to the control group. Other studies showed that geriatric units lead to shorter length of stay and fewer readmissions, ultimately decreasing hospital costs.18,19 One study demonstrated a longer length of stay but less frequent readmissions, and, therefore, overall cost savings.20

(Continued on next page)

Functional Decline

Functional decline and delirium are two major potentially preventable predictors of morbidity and mortality in the hospitalized elderly. The preservation of a patient’s functional well-being during hospitalization is a fundamental goal of medical care and a measure of success of a healthcare system.4 Although not usually the focus of hospital care, functional outcomes are important determinants of quality of life, physical independence, cost of care, and prognosis in older patients.17 For many people, the hospitalization is followed by an irreversible functional decline and change in quality of life.3

Functional status is defined as the interaction between daily behaviors needed to maintain life (ADLs) and one’s physical, cognitive, and social functioning level.21 Nearly one-third of hospitalized patients decline in the ability to perform one or more ADLs when compared to their preadmission baseline.22 The act of hospitalization for an acute medical illness contributes to the 20-60% incidence of functional decline in elderly patients. A conceptual model of the “dysfunctional syndrome,” described by Palmer et al,17 is the interaction between acute illness or impairment and the hospitalization; the hospital is referred to as a “hostile environment.” Chronic disease and psychosocial factors (such as depression) may worsen the patient’s physical impairment and result in a “dysfunctional” older individual upon discharge. Geriatric units help to prevent patients from losing functional capacity.12,20

Functional decline is significantly associated with mortality, re-hospitalization, and institutionalization. An assessment of one’s own ability to perform ADLs before a hospitalization does have a predictive validity. It is very important to inquire about previous function on admission, as this may be a strong predictor of function and survival.23 The Hospital Admission Risk Profile (HARP)4 is a simple, practical, validated instrument that includes one’s age, level of instrumental ADLs before admission, and Mini-Mental State Examination score.24 This derived score can stratify risk of functional decline at discharge and at 3-month follow-up. Patients in high-risk categories are significantly more likely to be institutionalized for long-term care. Longer hospital length of stay leads to further decline in function. Using HARP may help target vulnerable patients in need of comprehensive discharge planning, geriatric assessment, and post-hospitalization rehabilitation.4

Delirium

Delirium is defined as an acute disorder of attention and cognition. Incident delirium occurs in 25-56% of elderly hospitalized patients. Delirium results from the interaction of a vulnerable host and the “hostile” environment of the hospital. The vulnerable host is defined as the patient and his or her predisposing conditions upon admission to the hospital, such as cognitive impairment, severity of illness, and visual or hearing impairment. The “hostile” environment of the hospital includes adverse medication effects, procedures, sleep deprivation, immobilization and hospital-related infections.25 Patients with incident delirium are at a higher risk for nursing home placement or death.26 Patients with delirium often have functional decline and increased use of restraints in the hospital. Primary prevention is probably the most effective strategy in treating and decreasing the incidence of delirium.27

The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) is a validated tool, administered at the bedside to identify patients at risk for delirium. Hallmark signs of delirium assessed in the CAM are acute onset and fluctuating course of mental status, inattention, and disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness. The CAM uses four well-documented risk factors, including visual impairment, severity of illness, preexisting cognitive impairment, and dehydration, to identify patients at high risk for delirium. This tool enables physicians to minimize contributing factors in these targeted individuals.25 By targeting these factors, one can reduce incident delirium.26 This instrument has been proven to be both very sensitive and specific.

Efforts to prevent delirium extend beyond the hospital stay. By targeting specific risk factors, the adjusted total annual long-term nursing home costs and total days of care are lower.28 Delirium at discharge is associated with a high rate of nursing home placement and mortality within the next year.26

Acute Care Models

These concepts and ideas of geriatric assessment and multidisciplinary collaboration can extend beyond the walls of one geographical unit. The Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP) is a hospital-wide, volunteer-driven model of care focused on preventing delirium and functional decline in frail elders.29 This cost-effective model originated in a university teaching hospital and has been replicated on numerous occasions in the community. The intervention protocols target six delirium risk factors: (1) cognitive impairment; (2) visual/hearing impairment; (3) immobilization; (4) psychoactive medication use; (5) dehydration; and (6) sleep deprivation. Volunteers are trained to orient and lead patient activities, use adaptive equipment in communicating with elders, and mobilize patients throughout the day. Volunteers assist with meals during the day and deliver nonpharmacological methods to help patients sleep at night. This program significantly improves quality of care, patient and family satisfaction, and hospital outcomes in both delirium and functional decline.30,31

Providing acute hospital-level care in a patient’s home is an innovative alternative to hospitalization.32,33 In a survey in 2000, 46% of patients desired treatment at home only if conditions and outcomes were equivalent to those in the hospital. Comfort and safety were the two greatest concerns with regard to sites of care.33 One hospital-at-home model showed a decrease in use of restraints and incident delirium, shorter length of stay, and lower cost.32 Home treatment team patients averaged fewer hospital days in the year following a home-treated acute illness.34 There are a limited number of studies in this area, and continued research is needed.

Transitions of Care

The time period following an acute illness in the frail elderly is extremely critical. As healthcare is changing, patients are no longer cared for by a sole physician. A 2001 Harris poll commissioned by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation reports that, on average, older persons with one or more chronic conditions see eight different physicians over the course of a year. Practitioners who operate in silos, without a common care plan, adversely affect elderly patient care.35

Transitional care is defined as a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of healthcare as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care. Patients are at risk during the transition of care for medication errors, service duplications, and inappropriate care. Care plans often “fall through the cracks.” Communication between care providers is an imperative part of patient safety. Although verbal communication is ideal, in order to be effective, a care transition should include a plan of care, a summary of care thus far, advance directive, updated problem list, baseline physical and cognitive functional status, medications, allergies information, and contact information for caregivers and the primary care provider.36

To minimize poor outcomes, patients need to be prepared for what to expect at the next site of care. Coleman and colleagues37 empower patients and caregivers with tools, and support and encourage them to become more active in the transition from hospital to home through “care transition interventions.” Four entities are described: (1) medication self- management; (2) patient-centered records; (3) primary care and specialist follow-up; and (4) knowledge of “red flags” indicative of a worsening condition. The intervention group was assigned a transition coach upon discharge to home. In addition, they received their personal health record and a series of visits and telephone calls. Those who received this intervention were half as likely to return to the hospital as those who did not receive the intervention.37 Advanced practice nursing-centered discharge planning and home care interventions in at-risk elderly patients have shown to reduce readmissions, lengthen time between discharge and readmission, and decrease costs.38-40

The National Quality Forum and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations have expressed a commitment to patient safety during the time of care transition. The Society of Hospital Medicine recently received a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation to develop interventions to improve the transitions of care in elderly adults at the time of hospital discharge. The San Francisco Department of Aging and Adult Services is currently using information technology to improve geriatric care across settings with an Internet-based, online care management program that enables providers to exchange important information.36

Conclusion

As the population continues to age, we must be aware of the potential hazards of the hospital on frail elderly persons. We must utilize the strategies described to provide an effective, safe physical environment and recognize risk factors for functional decline and delirium upon admission. Interdisciplinary care teams must target these vulnerable patients to facilitate an effective discharge plan. Though the barriers to effective transitioning of patients are multifactorial, perhaps the future will bring changes in healthcare reimbursement and the use of performance measures to enhance the transitions of care for the frail elderly. After all, in the words of Dr. Warren, “Medicine has responsibilities towards the elderly sick and infirm, equal to any other section of the community and must undertake these if it is to remain worthy of its high traditions.”

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgments The authors would like to extend their gratitude to Nalaka Gooneratne, MD, Bruce Kinosian, MD, and Ravishankar Jayadevappa, PhD, for their assistance in the preparation of this article.