Screening and Assessment of Late-Life Depression in Home Healthcare: Issues and Challenges

Introduction

Depression is twice as prevalent in the home healthcare service sector1 as in primary care,2 is persistent, and is associated with disability, medical illness, and pain. Unfortunately, only 12% of persons with major depression receive adequate depression treatment.1 Home care recipients with depression fall more frequently.3 Depression is an independent predictor of overall poor compliance4 and may exacerbate other common chronic medical conditions in the elderly.

There is a critical need for an effective, valid, and reliable method for detecting late-life depression in home care recipients. Depression impacts an individual’s overall health and well-being.5,6 The failure to recognize and treat depression is associated with increased morbidity, as well as a higher risk of suicide and mortality from other causes.7 There are several scientifically proven treatment options for late-life depression,7,8 but these remain underutilized. Pharmacologic treatment, short-term psychotherapies (problem-solving therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy), and a combination of antidepressant medication and psychotherapeutic approaches are effective for treatment of depression in older adults.7-10

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening for depression in adults if there is a system in place for satisfactory diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up; home care certainly can provide for such an infrastructure.11 The rationale for this recommendation is that benefits from screening are unlikely to be realized unless such systems are in place.

Home Care

Home care is broadly defined as any diagnostic, therapeutic, or support service provided at home. It encompasses a wide range of services that are provided by a diverse group of professionals, including physicians, pharmacists, nurses, optometrists, psychologists, dieticians, social workers, and speech, physical, and occupational therapists. Home care nurses provide greater than 85% of all skilled services,12 and according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 117,419 registered nurses and 52,294 licensed practical nurses worked at Medicare-certified home health agencies in 2004.13 Medicare is the leading payer for home care services for older adults. The majority of home care is provided to patients after discharge from an acute hospital stay.

Improved screening and assessment for depression in late life is required for identifying older adults who could benefit from treatment or services. One role of home care nurses and therapists at Medicare-certified agencies is to assess individuals for signs and symptoms of depression. However, nurses14,15 and therapists16 may require training to accurately screen for depression and make mental health referrals when indicated. Another way to increase prospective screening for, and treatment of, depression would be to encourage physicians to inquire directly about depression symptoms in their home care patients. Performance of physician home visits would be another avenue for depression recognition; however, the number of homebound patients in the United States is very high, and physicians make only 1.5 million visits annually.17

Why Is Screening for Depression in Older Home Care Patients Not a Routine Practice?

Detection of depression is complicated by a number of barriers at the system, clinician, and patient levels, including:

Healthcare System and Policy:

• There are currently insufficient regulatory and economic incentives to encourage screening for depression in home care. Medicare covers and makes payments for screening for a limited number of potential disease processes to determine whether medically necessary care is needed; however, the law currently does not include routine screening for depression.18,19 Even if depression is detected, it is not a mandatory quality indicator. Home care agencies can obtain only a small increase in prospective payment when diagnosing or treating depression directly (C. Blackford and K. Walch, division of Home, Health, Hospice and HCPCS Center for Medicare Management, oral communication, March and April, 2007).

• There are insufficient psychiatric services available for homebound older adults.20

• Older adults with depression are frequently referred for home care services without depression-related information.21

Clinician:

• Depression detection efforts may require additional training.14-16

• Time consumed by coexisting medical illnesses does not allow for depression detection.22

• A misperception exists that depression occurs inevitably as a result of aging or chronic medical illness.23

• Detection can be hindered by the coexistence of medical or neurological disease symptoms that may be similar to those of depression.24

Patient:

• Older adults often find physical illness to be more acceptable than psychiatric illness. Because of this, they tend to report physical or somatic symptoms but not emotional ones.24

• Individuals from different cultural backgrounds may vary in the words or expressions they use to describe their feelings and symptoms; this makes the detection of depression a challenge.25

• The stigma associated with mental illness still persists, and as a result, persons with depression may be less likely to report emotional symptoms and to seek help.8

Depression Screening

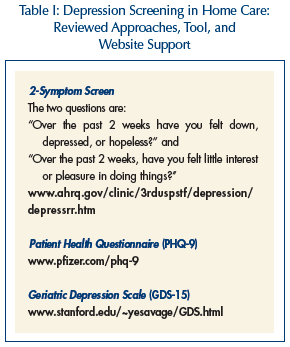

The USPSTF concluded that, “there is little evidence to recommend one screening method over another, so clinicians can choose the method that best fits their personal preference, the patient population served, and the practice setting.”26 In the home care setting, there is currently no identified best-practice standard for depression screening. Due to the paucity of research evaluating the performance and effectiveness of depression screening in this setting, an evidence-based recommendation is not possible; therefore, we have identified three approaches that are brief and appear feasible with agency support and education (Table I).

The USPSTF concluded that, “there is little evidence to recommend one screening method over another, so clinicians can choose the method that best fits their personal preference, the patient population served, and the practice setting.”26 In the home care setting, there is currently no identified best-practice standard for depression screening. Due to the paucity of research evaluating the performance and effectiveness of depression screening in this setting, an evidence-based recommendation is not possible; therefore, we have identified three approaches that are brief and appear feasible with agency support and education (Table I).

2-Symptom Screen

Screening for the cardinal or gateway symptoms of depression, “depressed mood” and “diminished interest or pleasure in most activities,” has been shown to be an effective screening method.27 The USPSTF concluded that asking two simple questions about “depressed mood” and “diminished interest or pleasure in most activities” may be as effective as using longer instruments.11 The two questions are: "Over the past 2 weeks, have you felt down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “Over the past 2 weeks, have you felt little interest or pleasure in doing things?” This approach to depression recognition is consistent with the diagnostic criteria (ie, those from the fourth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-IV]).25,28 At least one of these symptoms must be present consistently for two consecutive weeks, according to diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and proposed criteria for minor depression.25

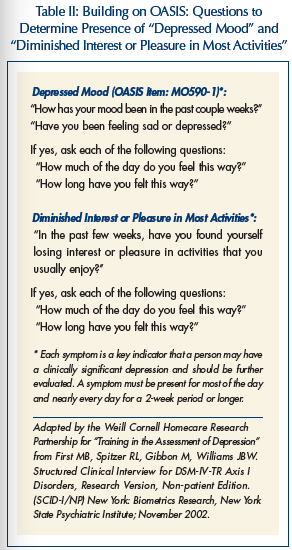

The Outcome and Assessment Information Set (OASIS) provides a standardized, recurrent opportunity for detection of key symptoms of depression. OASIS required at the “Start of Care,” “Resumption of Care,” and “Discharge” from a Medicare-certified home care agency includes depression-related items that must be answered.29,30 Using OASIS as a platform for depression recognition increases the feasibility of widespread use, avoids adding another measure that would increase the already lengthy required assessment, and does not reinforce the idea that depression is different from other conditions. OASIS is not intended to be a comprehensive assessment; it should be incorporated into a complete patient assessment with all of the necessary elements.

Recently, a randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure Program found that an OASIS-focused home care nursing educational intervention resulted in an increase in depression detection by home care nurses, and in appropriate referrals made for depression symptoms.31 In accordance with depression diagnostic criteria, home care nurses were trained to ask specific questions for depression detection (Table II), as screening requires both direct questioning and observation. In this approach, positive responses about “depressed mood” and/ or “diminished interest or pleasure in most activities” require follow-up with additional questions (ie, pervasiveness, persistence, and evaluation for suicidality32,33). This approach is consistent with that of the USPSTF,11 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) OASIS instruction,29,30 and can be used anytime throughout the home care admission process, since screening may not occur on the already busy first nursing visit, which is consistent with physician behavior.34 Marcus et al35 reports that this detection approach was successfully extended to physical therapists, speech therapists, and occupational therapists, and Gellis et al36 provided depression detection training to home care social workers with positive results. Future research should examine utilizing home health aides to detect depression, as they often provide most of the direct care.

Recently, a randomized controlled trial funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure Program found that an OASIS-focused home care nursing educational intervention resulted in an increase in depression detection by home care nurses, and in appropriate referrals made for depression symptoms.31 In accordance with depression diagnostic criteria, home care nurses were trained to ask specific questions for depression detection (Table II), as screening requires both direct questioning and observation. In this approach, positive responses about “depressed mood” and/ or “diminished interest or pleasure in most activities” require follow-up with additional questions (ie, pervasiveness, persistence, and evaluation for suicidality32,33). This approach is consistent with that of the USPSTF,11 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) OASIS instruction,29,30 and can be used anytime throughout the home care admission process, since screening may not occur on the already busy first nursing visit, which is consistent with physician behavior.34 Marcus et al35 reports that this detection approach was successfully extended to physical therapists, speech therapists, and occupational therapists, and Gellis et al36 provided depression detection training to home care social workers with positive results. Future research should examine utilizing home health aides to detect depression, as they often provide most of the direct care.

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

The 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) includes nine items that correspond to each of the nine symptoms of depression from the DSM-IV-TR.37 This makes it straightforward, and it can be used for monitoring treatment response as well. One study examined the performance of the OASIS depression assessment versus the home care nurse–administered PHQ-9 in screening for depression in older adults.38 The authors concluded that the PHQ-9 “is likely to identify patients who are undetected by Medicare mandated OASIS” (page 13).

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15)

The 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) is a depression screening tool developed for use in older adults. It had been validated for community-dwelling, hospitalized, and institutionalized older adults.39 The GDS-15 has several advantages: short length, administration time, and simple yes-no format. The GDS can be administered as a self-report or by oral interview.40,41

(Continued on next page)

Agency Support and Staff Education

In order to implement or enhance depression screening in home care, the agency may first want to consider reviewing its internal policy on making referrals for positive screens or suspected cases of depression. This is consistent with the mandate by Medicare for certified agencies, which requires annual review of policies and administrative practices “to determine the extent to which they promote patient care that is appropriate, adequate, effective, and efficient”42 (Interpretive Guideline 484.52, G248). Another important step in improving depression detection is not only to provide staff education on how and when to conduct the screen, but also to provide information about depression itself (ie, prevalence, clinical characteristics, consequences of untreated depression, and benefits of treatment). In two successful studies where the aim was to improve depression detection by the home care nurse, both interventions used a mixed instructional approach (ie, didactic and interactive), and included patient interviewing techniques, discussion about barriers to depression identification encountered by the home care nurse, and role plays that provide the opportunity to practice patient interviewing.31,38

Referral for Evaluation

A positive screen for depression prompts the need for further evaluation by the patient’s physician, psychiatric nurse, social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, or other mental health provider. Further investigation of a positive screen may not always result in finding depression that meets diagnostic criteria, but persons with depression symptoms who are in need of intervention may be uncovered.

Depression detection efforts require that the home care agency establish a procedure for notifying physicians and options for evaluation of suspected cases with physician collaboration. Related research has found that communicating depression-related information to the physician may be problematic22; a structured communication approach may be helpful.43

When available, referral to a psychiatric nurse for an evaluation of a positive depression screen is one alternative; this requires physician notification to comply with a CMS mandate that the treating physician must approve all changes in the treatment plan, including a psychiatric nurse evaluation. Another alternative for evaluation of depression symptoms in agencies that have medical social services is an evaluation by a social worker with mental health expertise; per the State Operations Manual, “[the] social worker assists the physician and other team members in understanding the significant social and emotional factors related to the health problem [and] participates in the development of the plan of care…”42 (Interpretive Guideline, 484.34, G195-196). Beyond the home care agency, community resources may be available in many areas to perform patient evaluations, give guidance to healthcare providers, and be a valuable resource to families.

Conclusion

There is good scientific evidence that training home care nurses to detect depression symptoms will increase appropriate mental health referrals for further evaluation. Depression screening and appropriate referral by the home care therapist (physical, speech, and occupational) and social worker are additional untapped opportunities for improving depression care. However, financial and regulatory incentives need to be brought into alignment with the need for the screening and treatment of depression. Physician awareness about options for depression evaluation in the home care setting will also help in better addressing the needs of older adults with depression receiving home care services.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Martha L. Bruce, PhD, MPH, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Department of Psychiatry; Carol Blackford, MPP, Director, Division of Home Health, Hospice, and HCPCS Center for Medicare Management, CMS; Kathleen Walch, BSN, RN, Nurse Consultant, Division of Home Health, Hospice and HCPCS; and Kit Scally, RN, MSPA, CNM, Insurance Specialist, Division of Practitioner Services, Physician Payment Policy/CMS, for reviewing the manuscript. Supported by NIMH grant K01 MH066942. The video package “Depression Recognition and Assessment in Older Homecare Patients” is marketed and distributed by Hopkins Educational Resource. The Weill Cornell Homecare Research Partnership was developed as part of an Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure grant funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R24 MH64608).