Treatment of Alcohol-Related Problems in the Elderly

Although figures vary from one study to another, available evidence indicates that alcoholism in the elderly is underdiagnosed and undertreated.1 Community studies generally have shown that about 2-3 percent of men over the age of 65 years meet criteria for alcoholism, with the incidence in women being perhaps one-third of that.2,3 When the focus is shifted to the medical office or the inpatient setting, the figures may increase tenfold, and are usually even higher for elderly persons seen in the emergency room.4 Furthermore, there is a general consensus that with the aging of the “baby boom” generation, these figures will increase significantly.

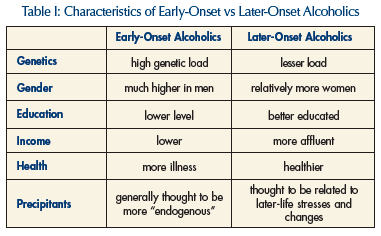

Among older drinkers there appears to be two different groups in terms of age of onset of alcoholic drinking (Table I).5 “Early-onset” alcoholics tend to comply with the common stereotype of the chronic alcoholic. They typically begin as teenagers or in their early twenties, and often impair their health, vocational life and personal relationships severely as they progress from youth through middle age. Many do not reach old age for obvious reasons. “Later-onset” alcoholics are mainly people who drank moderately, or even rarely, but then either increased their intake in association with the changes brought about by the aging process, or ran into problems because they could no longer handle the amount of alcohol they consumed earlier in life. Among the physiologic changes that account for reduced tolerance in the elderly are a decrease in lean tissue and water, with a relative increase in fatty tissue. Accordingly, a given amount of alcohol is distributed in a smaller volume, and blood levels are higher. Also, older people have less alcohol dehydrogenase in their stomachs, so, again, a drink raises blood levels more than it did at a younger age. Furthermore, the elderly brain is far more sensitive to alcohol.

Evaluating a Patient with an Alcohol Problem

In order to assess the severity of a given patient’s alcohol problem, we inquire about the quantity and pattern of drinking. A “standard drink” contains between ½ and ¾ ounce of pure alcohol. This is approximately the amount in a shot of 80-proof liquor, a 12-ounce glass of beer, or a 5-ounce glass of wine. The current recommendation, from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, is that persons over age 65 limit their consumption to one standard drink per day, and to no more than two on any occasion. Women are more vulnerable to alcohol’s deleterious effects and are generally advised to drink less. (Guideline is available in Treatment Improvement Protocol # 26, available from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA].6 The reader is advised to visit the SAMHSA site on the Internet [https://samhsa.gov], as it is a source of valuable information and publications).

The terms at risk and problem drinking have been found useful in terms of evaluating severity. At risk is drinking that has not yet led to identifiable consequences, but which is likely to do so in the future. Problem drinking pertains to a pattern that has led to one or more adverse consequences. The labels of alcohol abuse and dependence define conditions of greater magnitude. Abuse generally involves major consequences in at least one area of functioning, while a dependence diagnosis requires widespread impairment, with the addiction essentially taking over one’s life. Actual tolerance and physical dependence are usually present to some degree, but are not required to make the diagnosis.

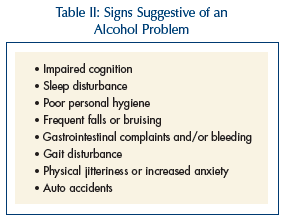

In order to accurately identify alcoholic problems in patients, clinicians must be actively searching for them and asking the right questions. Literature has consistently documented our failure to make the diagnosis and, perhaps of even greater concern, the lack of appropriate treatment even when the diagnosis is made.1 Elderly patients may present differently from younger patients, who often come to attention through work-related or legal problems. Signs that might be suggestive in the older patient include impaired cognition; sleep disturbance; decline in personal hygiene; frequent falls and bruising; gastrointestinal problems, including bleeding; gait disturbance; increased anxiety; and auto accidents (Table II).

In order to accurately identify alcoholic problems in patients, clinicians must be actively searching for them and asking the right questions. Literature has consistently documented our failure to make the diagnosis and, perhaps of even greater concern, the lack of appropriate treatment even when the diagnosis is made.1 Elderly patients may present differently from younger patients, who often come to attention through work-related or legal problems. Signs that might be suggestive in the older patient include impaired cognition; sleep disturbance; decline in personal hygiene; frequent falls and bruising; gastrointestinal problems, including bleeding; gait disturbance; increased anxiety; and auto accidents (Table II).

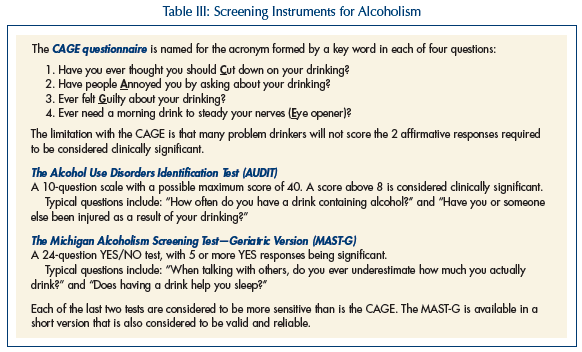

An assessment tool may be useful and can be part of a routine office visit. The CAGE assessment7 is a brief questionnaire that is easy to use but is not very sensitive. Two tools that have proven useful in the elderly are the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test-Geriatric Version (MAST-G)8 and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)9 (Table III).

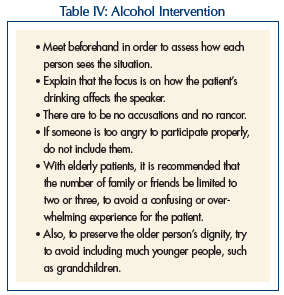

Having established the diagnosis, the next step is to enlist the patient in treatment. As is common knowledge, this may be a challenge. A frank discussion with the patient will help reveal the degree of denial or resistance. The author has found that older patients are generally responsive to family concerns. If a patient is seriously resistant, a family meeting, or even a formal intervention can be very effective. An intervention is a facilitator-guided process meant to confront patient denial. It is advised that clinicians receive appropriate training prior to leading an intervention on their own. Typically, there is an initial planning meeting with the concerned family or friends. The “ground rules” are laid out. These include the use of “I” statements, to focus on how the alcoholic behavior affects the speaker. There are no accusations or recriminations. Anyone unable to comply is eliminated. With elderly persons, it is recommended that only a few people attend, and that no very young people (eg, grandchildren) attend10 (Table IV).

Having established the diagnosis, the next step is to enlist the patient in treatment. As is common knowledge, this may be a challenge. A frank discussion with the patient will help reveal the degree of denial or resistance. The author has found that older patients are generally responsive to family concerns. If a patient is seriously resistant, a family meeting, or even a formal intervention can be very effective. An intervention is a facilitator-guided process meant to confront patient denial. It is advised that clinicians receive appropriate training prior to leading an intervention on their own. Typically, there is an initial planning meeting with the concerned family or friends. The “ground rules” are laid out. These include the use of “I” statements, to focus on how the alcoholic behavior affects the speaker. There are no accusations or recriminations. Anyone unable to comply is eliminated. With elderly persons, it is recommended that only a few people attend, and that no very young people (eg, grandchildren) attend10 (Table IV).

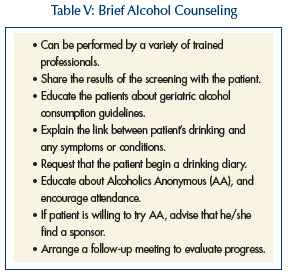

The type of drinking determines the next steps. In the case of at-risk or problem drinking, the patient does not require detoxification or inpatient treatment. If he is willing to engage, then his degree of denial and readiness for change are assessed. He may benefit from brief  alcohol counseling (BAC) (Table V). In some cases, a great deal can be accomplished with just a few brief encounters. The professional need not be a mental health specialist.

alcohol counseling (BAC) (Table V). In some cases, a great deal can be accomplished with just a few brief encounters. The professional need not be a mental health specialist.

Primary care physicians, advanced practice registered nurses, and others involved in general medical practice can learn to become effective in this area. The general elements involve educating the patient about his/her pattern of drinking as it compares to the norm, the relation of his/her drinking to symptoms and illnesses, and ways to enhance motivation and monitor change. Just a few conversations can bring about positive change.11,12 Some patients, however, may benefit from sessions with an experienced substance abuse professional, possibly utilizing a technique such as Miller’s motivational enhancement therapy.13

For those who meet criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence, more robust intervention is required. The severity of the withdrawal process is difficult to predict, due to personal variability and lack of accuracy of patient histories. An objective tool such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment (CIWA)14 should be used. It monitors intensity of withdrawal symptoms and can be used with an inpatient or outpatient.

The decision to initiate detoxification as an outpatient versus as an inpatient is an important and complex one. Some patients can be safely and effectively withdrawn in the outpatient setting. In order to assess the appropriateness of outpatient detoxification, a number of factors need to be taken into account. First, do we have access to a reliable history? This is relevant both in terms of accurate information about the current drinking pattern and in terms of prior experience with detoxification efforts. Also, it is imperative that a responsible caregiver be actively involved.

The time course of alcohol withdrawal is such that those who are likely to develop problems will show signs of autonomic hyperactivity within 8 to 16 hours after the last drink. The CIWA scale can then be used to assess the degree of withdrawal symptomatology. A moderate score would be between 8 and 15. In that range, one might choose to treat with an appropriate short-acting benzodiazepine and follow the patient closely, communicating with the patient and caregiver daily over the 5-7-day withdrawal period.

There are many patients for whom the inpatient setting would be more appropriate. As in all areas of clinical practice, one’s professional judgment inevitably plays a role. If the patient’s CIWA score is over 15, that could presage major problems. Also, a history of withdrawal delirium or seizures would call for hospital-based detoxification. Further, hospitalization is indicated for patients who are suicidal, who have complex medical and/or psychiatric comorbidities, or who lack adequate supports in the community. Additional benefits of hospitalization are lack of access to alcohol, break from the usual environment (which could be part of the problem), opportunity to obtain diagnostic and treatment services efficiently, and the opportunity to mobilize family and friends, which often occurs when someone is hospitalized.

Medications

Medication can play a variety of roles in treatment. Medications may be divided into those used for detoxification, those used to prevent relapse, and those used to treat psychiatric comorbidities. The standard drugs for withdrawal remain the benzodiazepines. The particular drugs recommended are those that are metabolized by conjugation alone, a process relatively undiminished in the elderly. Oxazepam and lorazepam are both widely used. The CIWA scale can be used every 4 hours to assess patient status, with a dose of medication being given for any score above 6 or 7. Anticonvulsants such as divalproex and carbamazepine have long been known to ameliorate withdrawal symptoms and are still being actively studied in this regard. It is not known whether they offer any specific benefit over benzodiazepines in the geriatric population.

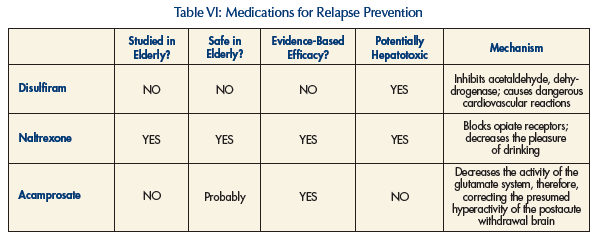

Drugs currently available for relapse prevention include disulfiram, naltrexone, and acamprosate (Table VI). Disulfiram, which blocks the action of aldehyde dehydrogenase, causes the accumulation of acetaldehyde when combined with alcohol. This reaction can lead to serious and extremely unpleasant consequences. It is potentially dangerous in the elderly, and should never be given to a patient with cognitive impairment. The effect can last as long as 2 weeks after the last dose. Interestingly, studies usually fail to show efficacy, which is thought to be due to noncompliance. Naltrexone is an opiate antagonist that was approved for treatment of alcoholism in 1995. Apparently, both the pleasure derived from drinking and the craving to drink are related to the endogenous endorphin system.

Two landmark studies, both published in the Archives of General Psychiatry in 1992, demonstrated the safety and efficacy of naltrexone in reducing craving and relapse in a general adult population.15,16 Oslin and colleagues17 studied a group of veterans between ages 50 and 70 years and also found evidence of safety and efficacy. In addition, Oslin et al18 compared older adults (mean age, 62.6 yr) with younger adults (mean age, 41.7 yr) in terms of compliance with, and efficacy of, treatment with naltrexone and supportive psychosocial therapy. They found that the older adults did better in terms of treatment adherence and reduced relapse rates.18

A recent development has been the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of monthly injections of long-acting naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism. Initial studies are favorable in terms of efficacy and tolerability.19 There have not yet been any studies in the elderly. There were concerns about increases of hepatic enzymes in some early studies of naltrexone, but the doses used were significantly higher (eg, 300 mg daily) than the presently recommended 50 mg per day. A guideline for prescribing either naltrexone or disulfiram, which also can raise hepatic enzymes, has been to avoid prescribing if hepatic enzymes are doubled, and to stop the medication if they go up to threefold.

Acamprosate was approved by the FDA largely on the basis of data from European studies. Its purported mechanism of action involves stabilization of the cerebral glutamate system. It would, thereby, presumably reduce some of the cerebral dysfunction thought to underlie the protracted abstinence syndrome present in those who have drunk heavily over long periods of time. It is a drug with a relatively benign side-effect profile and would appear to be safe in the elderly, although no specific studies have been done in older adults. In a recent large multicenter study, acamprosate was significantly less effective than naltrexone on all measures.20

Among the most important comorbid conditions are clinical depression, anxiety disorders, and dementia. As a large percentage of alcoholics experience depression at the outset of treatment, and then recover in just a few weeks or less, it is recommended to avoid prescribing antidepressant medications during the first week or two. Antidepressants appear to be helpful in reducing alcohol intake in patients with true clinical depression. However, they do not seem to show the same effect in persons without depression. In fact, there are a small number of studies that have shown increased drinking in a subset of alcoholics treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).21,22

For anxiety disorders, the challenge has always been to find a medication that will not, itself, be abused. First choice is generally an SSRI or selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SSNRI). Of course, benzodiazepine use in this population is doubly fraught with potential dangers. In addition to the usual geriatric concerns about impaired cognition, coordination, and alertness, we have the danger of addiction and of dangerous combination with alcohol. Although it has never been popular among clinicians, buspirone is a drug that is safe in this population. Older patients may have dementia symptoms for a combination of reasons. However, primary alcohol appears to be as a causative factor; a trial of a medication for Alzheimer’s disease may be worth considering.

Follow-Up Support

In terms of follow-up and relapse prevention, there is evidence that older people may do better in programs with patients of similar age.23 For example, a patient might do better in a general geriatric day treatment program than in a mixed-age alcoholism program. If available, a geriatric day program could be supplemented with attendance at general adult relapse prevention groups. (Such programming is available where the author works, at the Institute of Living in Hartford, CT.)

Of course, the geriatric population is enormously varied in terms of level of health and vigor. It is certainly true that many older patients would do better and feel more comfortable in a mixed-age setting. Patients should be referred to Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). It should be noted that about one-third of AA attendees are over age 50. This is a setting that is quite supportive and that emphasizes that “it is never too late.” It is recommended that the patient acquire a sponsor, and that contacts be made with others for support, and for help with transportation, if that is a problem. And, finally, supportive psychotherapy may be helpful to many patients. The author has had a long career in geriatric psychiatry, and has found that what some older patients may lack in flexibility, they more than make up for in sincerity and a true investment in the relationship. Older alcoholics may be carrying an enormous burden of guilt and remorse that may respond every bit as well to skilled psychotherapy as to medication.

The author reports no relevant financial relationships.