Detecting Financial Exploitation of Vulnerable Adults: Guidelines for Primary Care Providers and Nursing Home Medical Directors

Case 1

Mrs. B is a 72-year-old widow with a history of mild cognitive impairment. Currently, she lives in the same home in which she raised her family and is independent in all of her basic and instrumental activities of daily living. At her daughter’s suggestion, she recently hired a neighbor to assist with homemaking tasks and home maintenance duties. Their relationship flourished, and the neighbor offered to help Mrs. B with her financial responsibilities. Mrs. B eagerly provided her neighbor with all of her financial documents, because handling her late husband’s accounts had become a burden to her.

Months later, Mrs. B’s daughter places a frantic telephone call to her mother’s primary care physician. She has realized that all of her mother’s accounts have been transferred to the neighbor, and the neighbor is nowhere to be found. Mrs. B’s physician is unsure of how to proceed.

Case 2

Mrs. C is an 82-year-old woman who was recently transferred to a skilled nursing facility from the local hospital, where she was treated for a right hemispheric stroke. She requires daily physical and occupational therapy on the weaker side. Before admission to the hospital, she lived on a farm with her 52-year-old son. Mrs. C owns the farm and maintains the title. Her son works on the farm and lives in its home with her. She has a past history of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and macular degeneration. On examination, she has dense left-sided weakness and marked difficulty arising in bed. Her Mini-Mental State Examination score is 22 out of 30 and indicates significant difficulty in recall.

After 90 days, she has made some improvement in gait; however, the physical and occupational therapists believe that her function has plateaued at its current level. Despite improvement, she still requires assistance with walking, dressing, and toileting. After a care conference meeting, her son is adamant about taking his mother home. She is agreeable about going home with her son; however, the medical director, physical therapists, and nurses are concerned about her safety without 24-hour supervision.

Introduction

Financial abuse is among the top three most common types of elder abuse, with more than 38,000 cases reported annually.1 Despite the topic’s high profile in financial, legal, and political forums, it remains relatively absent from the published medical literature and medical practice. Healthcare providers do not often counsel patients on financial matters because this aspect of care is outside the realm of traditional clinical practice.2

Older adults are at increased risk of financial exploitation for several reasons. Often, they possess substantial net worth and better credit than their younger counterparts, making them frequent targets.3,4 Older adults may require the assistance of others in making financial decisions because of cognitive and physical impairments.4 Further, the widespread use of the Internet and other emerging technology has allowed for the development of novel schemes intentionally targeted to older adults. Not surprisingly, Adult Protective Services (APS) agencies annually investigate more cases of financial abuse than of physical or psychologic abuse.1

With the sustained growth of the U.S. elderly population, both in the community and in skilled nursing facilities, it is now imperative that healthcare providers develop the skills necessary to recognize and report cases of financial abuse. Healthcare providers are often in a position to detect financial abuse among their older patients. This article reviews the defining features, epidemiology, ethical considerations, and legal issues of financial abuse from the perspectives of both the community and the skilled nursing facility. We also outline practical strategies that a primary care provider or medical director can take to prevent financial abuse and to manage cases in which it is suspected.

Features of Financial Abuse

Financial exploitation is characterized by the misappropriation of an impaired person’s funds, property, or assets by dishonest or self-serving means.5 Analogous frameworks include fiduciary abuse, material abuse, financial abuse, fiscal abuse, financial mistreatment, economic victimization, misuse of guardianship or conservatorship, misuse of powers of attorney, embezzlement, and undue influence.2,6 Wilber and Reynolds6 describe the two persons who characterize fiscal abuse: the vulnerable elder and the exploitive perpetrator.

One of the challenges in describing and documenting financial abuse stems from the variability in terminology between disciplines and the laws in different states. In Minnesota, for example, criminal law defines vulnerable adult as an individual aged 18 years or older who has one of the following four situations: (1) is a resident of an inpatient facility; (2) receives services, such as adult foster care, from a facility required to be licensed to serve adults; (3) receives home healthcare services from a licensed provider or under the state assistance program; or (4) has a mental health or physical condition that, regardless of residence or whether any type of service is received, impairs the person’s ability to provide his or her own care independently and, because of the infirmity and the need for assistance, has an impaired ability to protect against personal maltreatment.7,8 The National Association of Protective Service Agencies defines vulnerable adult more loosely: “a person who is either being mistreated or in danger of mistreatment and who, due to age and/or disability, is unable to protect himself or herself.”

Although there is no “typical” victim or perpetrator, a number of predisposing characteristics have been described. Risk factors that predispose older adults to financial abuse include advanced age (>75 years), female sex, cognitive impairment, physical disability, minimal social capital, marriage status of unmarried or widowed, and financial independence.9,10 On the basis of these risk factors, almost all residents of long-term care facilities are at risk of financial abuse.

Perpetrator characteristics include establishment of a caregiving relationship with the older adult; certain psychologic conditions, such as antisocial character disorder; economic dependence on the victim; and substance abuse.9 The perpetrator may or may not be a person familiar to the victim. However, studies have shown that 60% of perpetrators were adult children of the elderly victims.11 A perpetrator may portray himself or herself as a financial adviser, a handyman, a housecleaner, or a personal caregiver.

Healthcare providers and skilled nursing facilities may also be involved with financial exploitation. Financial abuse in the institutional setting often takes the form of inappropriate or fraudulent billing of the resident by the facility or agency. Healthcare providers also may fraudulently bill the resident, although this fraud typically occurs through a third-party payer.

Financial abuse fits into one of two general categories: theft of income and theft of assets. Theft of income is the more common category of financial abuse among adults who live independently in the community (“community-dwelling adults”). It typically occurs in transactions of less than $1000.12 Community-based examples include door-to-door scams for “home improvement,” double-billing for goods or services, and solicitation of donations for fraudulent charities. In contrast, theft of assets occurs on a much larger scale and may include tax manipulation, forcible transfer of property, professional investment swindles, identity theft, bank employee fraud, or advance-fee fraud.

Perpetrators use a broad range of abuse tactics, such as deception, misinformation, intimidation, and withheld information. Another area of growing concern is identity theft, It may occur anonymously or by a known associate who inappropriately uses the person’s personal identifiers.

Healthcare providers face a growing and increasingly unsettling problem of financial abuse among residents of long-term care facilities. In contrast to exploitation of community-dwelling adults, financial exploitation of residents in long-term care facilities typically involves misappropriation or theft of assets. Residents often have cognitive impairment or it develops over time; even small changes in cognition can affect a person’s ability to manage his or her own financial assets.13 Misappropriation of a frail resident’s assets can result in deprivation of needed care, medications, or food. A resident can be removed from a care facility for purely financial reasons. Individuals may misappropriate a resident’s assets by failing to pay bills or by using the resident’s resources for their own needs.

Family members are responsible for the majority of the misappropriation of assets.14 They may inappropriately use assets for a number of reasons, including access to income streams (eg, social security, pension) and preservation of an inheritance. As such, it is often a county financial worker or long-term care facility business office staff who first recognizes evidence of fiscal abuse.

Epidemiology of Financial Abuse

In 2003, results of a national survey of state APS agencies revealed that 22% of APS investigations involved financial exploitation of older adults. Nearly 15% of substantiated APS cases involved financial exploitation, making it more common than all other types of abuse except self-neglect (26.7%) and caregiver neglect (20.8%).1

Population-based approaches aimed at measuring the frequency, clinical course, and outcomes of elder exploitation are lacking in the published geriatric and medical literature because of methodologic challenges, including underreporting, incomplete sampling, selection bias, and nonsystematic data collection.15 Victims are often hesitant to report exploitation because they feel threatened by the perpetrator, and many victims are unaware that the exploitation is occurring. For every reported case of elder financial abuse, an estimated four to five cases go unreported, making it difficult to determine the true incidence.16 State APS agencies collect case information regularly, but unique state-based legislation and differing data management systems do not allow for interstate collaborative efforts. Finally, no clearinghouse or federal agency requires the collection of data on elder financial abuse.

Role of the Primary Care Provider

Historically, providers have avoided discussions about financial matters with their elderly patients because this type of fiscal counseling has not been a customary part of the physician-patient encounter.2,17 Also, many providers lack the necessary training about what action to take when financial exploitation or elder mistreatment is suspected. Alpert and colleagues18 found that less than 40% of graduates from U.S. medical schools recalled formal education about elder abuse.

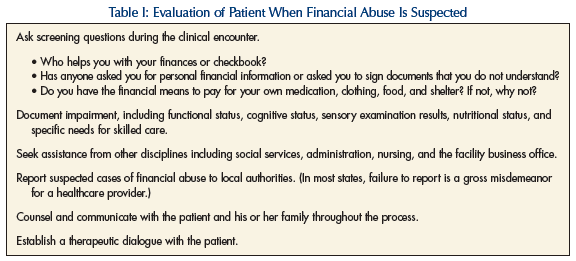

Primary care providers and medical directors are in a key position to detect financial abuse and elder mistreatment because a large proportion of their patients are vulnerable adults. These providers may have an established, trusted relationship with the older adult and are generally viewed as advisers. Additionally, healthcare providers may be called on to give expert opinion to law enforcement authorities or to the court system in an older adult’s regard. In a case of abuse, the key functions of the healthcare provider include identification, assessment and accurate documentation, and reporting (Table I).

Early Identification

Unlike the signs and symptoms associated with physical abuse and neglect, revealing physical findings are often lacking in financial exploitation. Financial abuse often remains concealed from both the medical provider and the patient until the situation is well advanced. Early identification is paramount, however, because financial abuse puts enormous emotional duress on the victim. Victims of financial abuse may be at increased risk of depression, decreased quality of life, and institutionalization.4 During the clinical encounter, screening for financial abuse can help raise awareness and facilitate communication between the patient and the provider.19

Clinical features of financial exploitation that may be seen in the community and in long-term care settings are outlined in Table II. At the later stages of financial abuse, signs of physical neglect may be present if the patient does not receive appropriate food, medications, or medical care. A visit to the patient’s home can be a helpful technique to gather important clinical information and facilitate the acceptance of necessary community services.

Use of an interdisciplinary team is of utmost importance. The team’s composition will vary, depending on the circumstances of the alleged abuse situation. Key team members may include the elderly person, family members, the power of attorney/conservator, the primary facility nurse or public health nurse, the victim’s primary care provider, a county or facility social worker, and the facility administrator. A social worker from the county Adult Protective Service Agency will often collect information about the situation and lead the investigation. This social worker is responsible for substantiating the case to state authorities and involving law enforcement. Additionally, each state has identified consumer advocates, also known as ombudsmen, who can handle complaints that affect the health, safety, and welfare of long-term care residents and add value to the team.

Assessment

After identification of suspected financial abuse, the clinician needs to determine whether the patient is vulnerable or impaired. The clinician should evaluate the patient’s functional status, frailty characteristics (eg, weakness, malnutrition, mobility disturbance), sensory disturbances, psychologic health, and cognitive function. Detailed documentation of key historical information about the suspected abuse situation and an assessment of vulnerability are imperative. The clinician needs to determine the patient’s cognitive capacity to make routine financial decisions. The determination of capacity by the healthcare team is often the cornerstone for enforcement of power of attorney or guardianship. If a nursing home resident or community-dwelling adult does not have the capacity to appreciate the consequences of his or her financial decisions, the person may benefit from the appointment of a conservator or the assignment of financial power of attorney.

Ethical and Legal Considerations of Reporting Financial Exploitation

In accordance with the ethical principle of beneficence, healthcare providers have a moral obligation to promote each patient’s welfare. However, providers must also consider the wishes of the patient or resident and respect his or her right to autonomy. Autonomy and self-determination refer to an individual’s ability to make an informed decision without duress or external pressure. Community-dwelling older adults and nursing home residents have the autonomy to allocate their assets however they choose. This combination of beneficence and patient autonomy creates conflict between the two, and thereby leads to the ethical dilemma that providers often face. The determination of decision-making capacity is fundamental to this process.

Each state possesses specific laws about elder abuse, and reporting is mandatory in 33 states. However, the terms of these laws differ between the states.20 Many medical providers hesitate to report suspected elder abuse because of their lack of experience or training in recognizing abuse, lack of knowledge about the reporting mechanisms, or perceived barriers in navigating the legal system.21,22 In states with mandatory reporting, however, it is the legal responsibility of the healthcare provider to report suspected or believed financial exploitation to the local APS agency or to a county social worker for further investigation. Minnesota laws pertaining to the mandatory reporting of abuse of a vulnerable elder permit a vulnerable adult to sue healthcare providers or other mandated reporters for damages caused by their failure to report financial exploitation to local authorities.23 Thus, there are both ethical and legal obligations to report financial abuse of at-risk older adults.

An exploited older adult has legal recourse, which may include filing a complaint with local police authorities so that the wrongdoer is prosecuted. Several states have passed laws that provide criminal penalties for various forms of elder mistreatment. For example, the Minnesota criminal code includes crimes of financial exploitation of a vulnerable adult and of deceptive or unfair trade practices against elderly or disabled persons.24,25 The law prohibiting deceptive trade practices against the elderly gives the attorney general statewide jurisdiction to prosecute this crime. Attorneys in elder law can be reliable legal resources for financial abuse victims. Currently, the Administration on Aging administers state grants to provide accessible legal assistance to vulnerable older Americans who are the victims of consumer fraud and other types of financial exploitation.

The Role of the Medical Director

In cases of financial exploitation, the role of the medical director of a skilled care facility focuses on direct medical care, administrative functions, and coordination of the interdisciplinary team. The role and expectations of the medical director have been outlined in the federal regulations (F501). Specific to financial exploitation, medical care is a core responsibility. Medical direction also involves the appropriate utilization of facility-specific guidelines. If those guidelines or policies are hindered because of financial abuse (withholding appropriate treatment, devices, or evaluation), the medical director has a role to ensure the policies are met or addressed. The medical director often provides direct medical care for residents; thus, the specific functions of the primary care physician (ie, determination of functional status, cognitive status evaluation, and reporting) remain important. These functions are particularly crucial when a resident leaves a facility and moves to a new living environment where the person may be at risk. However, not all medical directors serve as primary attending physicians in the long-term care setting.

In addition to direct medical care, the medical director also serves as an important link between the facility’s medical staff and its administrative, nursing, and social services staff. As such, he or she can provide a second opinion on questionable cases of capacity and can serve as a resource for the facility when questions arise about the medical necessity of visits or services for the resident. Medicare fraud continues to be an important concern for the federal government and the U.S. Office of the Inspector General,26 and appropriate use of medical equipment, visits, and services is an important facet of the medical director’s role. Law enforcement and the legal system are frequently involved in cases of financial exploitation. The medical director may be called upon for a medical opinion regarding the resident, or may be called upon to represent the facility.

Coordination of care and interdisciplinary team leadership are also within the federal statutes. Regularly scheduled Quality Assurance meetings represent an excellent time for the entire team to address the topic of financial abuse. Likewise, these meetings can serve as an ideal opportunity to address quality initiatives aimed at improving the detection of abuse and financial misconduct within the facility. The need for and benefits of collaboration between the facility social service director, attending and nursing staff, administrative staff, and medical director cannot be overemphasized.

Summary

Financial abuse of older persons is a burgeoning problem. Cases like those described in this article are both common and challenging to manage. Regardless of their place of residence, older patients are collectively at risk. Having no characteristic physical signs, this type of abuse can be difficult to detect during an initial clinical encounter. Nevertheless, providers of longitudinal geriatric care are in a unique position to identify and report suspected cases of material abuse. Additionally, geriatric medical providers need to continue efforts to raise awareness of this problem in their own communities, as well as to educate future generations of clinicians to both recognize financial exploitation and respond to suspected abuse situations.

Acknowledgment

Editing, proofreading, and reference verification were provided by the Section of Scientific Publications, Mayo Clinic.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.