Ask the Expert: Constipation

Q: How do you manage constipation in the long-term care setting?

A: There is no clinical definition of constipation. Physicians describe constipation as less than three bowel movements per week, while patients describe constipation as passing hard stools or straining to have a bowel movement. Thus, there is no agreement between the patient and physician. Because of this dispute about the definition, there is little correlation between self-reported constipation and number of bowel movement in epidemiologic surveys. The Rome Criteria defines constipation as outlined in Table I, a consensus definition used by experts for the primary purpose of use in clinical trials.

The prevalence of self-reported constipation and laxative use increases with aging, while the prevalence of stool frequency does not change with age.1,2 Constipation is more common in the elderly, African-Americans, women, and persons of lower socioeconomic class.

In frail elderly individuals, up to 45% reported constipation as a health issue. The prevalence of constipation is higher in nursing home residents, a finding not well explained by the increased use of laxatives, but which could be explained with higher use of medications and other comorbidities.3

Factors associated with constipation development in nursing homes include: race, decreased fluid intake, pneumonia, Parkinson’s disease, and presence of allergies.4 Congestive heart failure and the use of a feeding tube were two factors identified as having a protective effect.4

The average cost per long-term care resident with constipation is $2253.5 Health-related quality of life is reduced in patients with chronic constipation.6 The presence of constipation has been hypothesized to increase urinary tract symptoms, fecal incontinence, fecal impaction, and stercoral ulceration.7-9

CAUSES OF CONSTIPATION

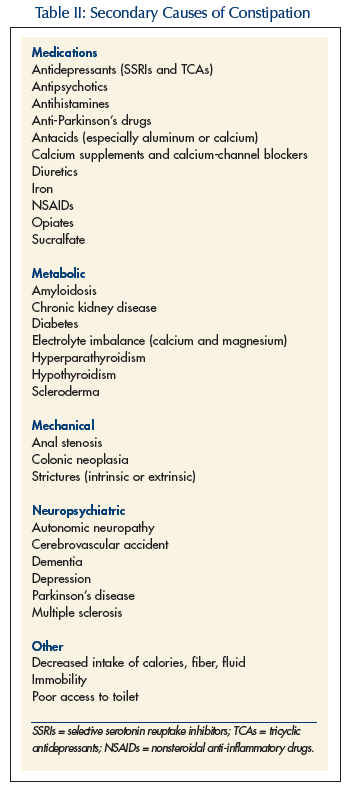

Causes of constipation can be divided into primary and secondary causes.

Primary causes of constipation could be classified into three groups: (1) normal transit constipation, (2) slow transit constipation, and (3) anorectal dysfunction. Secondary causes are outlined in Table II. The most common ones are medications and coexistent medical conditions.

EVALUATION OF CONSTIPATION

Regulatory guidelines require that a comprehensive patient assessment, the Minimum Data Set (MDS), be completed within 14 days of admission to a nursing home. The MDS addresses how the resident uses the toilet, transfer on/off the toilet, and bowel pattern elimination. It is important to address constipation from the start, as it could lead to impaction, decrease in activities of daily living, incontinence of bowel and bladder, and at times, delirium, which could lead to resident assessment protocol trigger. Bowel elimination continues to be an important indicator on the MDS on the quarterly/annual assessment forms.

The steps involved in the evaluation of constipation are outlined in Table III. In acute or subacute onset, it is important to exclude structural lesions such as neoplasia or volvulus. The presence of weight loss along with rectal bleeding and/or iron deficiency anemia also requires examination of the colon to exclude cancer.

Additional tests that are used in the evaluation of constipation but are rarely needed in nursing home patients include colon transit measurements, colonic manometry, anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion testing, and defecography. Of patients undergoing extensive exhaustive investigations, the cause of constipation is determined in only about 50%.10

TREATMENT OF CONSTIPATION

The best strategy for managing constipation is to divide the symptoms into degrees of severity. The first step is to take a careful history, remembering that the patient often is talking about an entirely different symptom complex. Patients may report that they are constipated, but when formally evaluated by daily diary during a 4-week period, only 45% of these patients had fewer than three bowel movements per week.11 The perception of hard stools or excessive straining is more difficult to assess objectively, and the need for enemas or digital disimpaction may be more clinically useful markers to corroborate the patient’s perceptions of difficult defecation. A careful history should explore the patient’s symptoms and confirm whether he or she is indeed constipated based on frequency (such as fewer than three bowel movements per week), consistency (lumpy or hard), or excessive straining, as shown by prolonged defecation time or digital evacuation of the rectum. Certainly, the patient’s complaints should not be ignored, but realistic goals of treatment need to be established.

A multidisciplinary approach is required for the evaluation and treatment of constipation: the physician assessing for predisposing disease states and medications; nurses and aides spending adequate time assisting patients with toileting and hydration, appropriate use of laxatives as needed, and adequate description of bowel movements; consultant pharmacists assessing predisposing medications and making recommendations for dosage reductions or agent changes as appropriate; and dietitians assisting with fluid content of the diet.

The treatment of constipation can be divided into nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic. A nonpharmacologic approach includes advice to the patient on regular bowel habits, exercise, and adequate fiber intake along with water. It might be difficult for residents in long-term care to follow these recommendations. Nursing home staff should encourage them to defecate first thing in the morning or 30 minutes after meals when the colonic activity is the greatest, and to take advantage of gastrocolic reflex.

Fiber should be encouraged in the diet of all nursing home residents. The daily recommended fiber intake is 2035 grams. Fiber is generally a safe, inexpensive, first-line approach, and improves stool consistency and accelerates colon transit time. In some studies, a high-fiber diet has been shown to be associated with lower laxative use;12 however, other studies show no beneficial effect from fiber.4 Another factor is adequate hydration; while general hydration and low calorie intake have been considered important risk factors for constipation in older adults, this has not been authenticated in studies.13,14 Increase in fluid intake might be helpful in dehydrated patients, but may rarely improve symptoms of constipation in those who are chronically constipated.15 Although immobility, reduced fluid, and reduced fiber intake are often implicated in the development of constipation, there is little evidence to support these myths. Reduced liquid intake does not appear to cause constipation,10 and, likewise, increased physical activity does not reverse constipation.16 Reduced calorie intake17 and increased psychological distress10 correlate well with constipation in the elderly, although the mechanism of the latter remains unknown.

A pharmacologic approach is the next step if the nonpharmacologic intervention fails. Pharmacologic agents used in the treatment of constipation are listed in Table IV. A systematic review found that increase in fiber intake and the use of laxative improved bowel frequency compared to placebo. The data concerning the superiority of treated individuals was inconclusive; also, there are limited data on the risk of laxative fiber preparations. There is no evidence-based guideline on the preferred order of using different types of laxatives.18

Studies with psyllium generally show improvement in stool form and frequency.19,20 While stool softeners are prescribed commonly, they have not been shown to be effective,21,22 and are not superior to psyllium.23-25

Osmotic laxatives include polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, sorbitol, magnesium salts, and saline salts. Saline and magnesium salts should be used with caution in patients with renal, liver, or heart failure. While there are no studies in older adults directly assessing PEG, in younger adults, when compared to lactulose, it showed efficacy, safety, and fewer side effects over a 6-month period.26 Lactulose improved stool frequency, reduced need for enemas, and reduced fecal impaction over a 12-week period.27 A randomized controlled trial of lactulose and sorbitol in older adults found no difference in laxative effect and no strong preference of one laxative over the other by the study subjects.28 Abdominal symptoms were similar between the two groups, except for greater complaints of nausea in the lactulose group. The cost of sorbitol is generally less and makes it a preferred agent for many patients. Vanderdonckt et al29 found in a 4-week trial that nursing homes residents (mean age, 84 y) given an osmotic laxative showed significant improvement in the number of bowel movements and consistency.

Osmotic laxatives include polyethylene glycol (PEG), lactulose, sorbitol, magnesium salts, and saline salts. Saline and magnesium salts should be used with caution in patients with renal, liver, or heart failure. While there are no studies in older adults directly assessing PEG, in younger adults, when compared to lactulose, it showed efficacy, safety, and fewer side effects over a 6-month period.26 Lactulose improved stool frequency, reduced need for enemas, and reduced fecal impaction over a 12-week period.27 A randomized controlled trial of lactulose and sorbitol in older adults found no difference in laxative effect and no strong preference of one laxative over the other by the study subjects.28 Abdominal symptoms were similar between the two groups, except for greater complaints of nausea in the lactulose group. The cost of sorbitol is generally less and makes it a preferred agent for many patients. Vanderdonckt et al29 found in a 4-week trial that nursing homes residents (mean age, 84 y) given an osmotic laxative showed significant improvement in the number of bowel movements and consistency.

Stimulant laxatives, when used in recommended doses and short duration, are unlikely to harm the colon. However, stimulant laxatives do result in electrolyte imbalance or abdominal pain in some patients. Senna-containing concentrate as part of a program that included stool softener and increased fiber, has resulted in improved bowel evacuation and prevention of fecal impaction in nursing home residents.30 Marchesi et al31 found in a 3-week trial with stimulant in hospitalized patients (mean age, 71 y) a significant improvement in the consistency of stools in the treated group.

The role of enema in the treatment of constipation is limited to acute situations. Any enema must be used with caution owing to the risk of colonic perforation. Soap enemas should not be used. Small-volume tap water enemas may be helpful in emptying the rectum; large-volume can also be used but can result in hyponatremia. Enemas containing phosphate have been described to cause hyperphosphatemia, especially in renal insufficiency patients.

Prokinetic agents stimulate propulsion along the gastrointestinal tract. Tegaserod, a 5HT4 agonist, improves the symptoms of constipation in adults but is not approved for people over the age of 65 years.32

Lubiprostone is the latest medication to receive FDA approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. It activates the specific chloride channels (CIC-2) in the lining of the small intestine after oral administration, thereby increasing intestinal fluids. Lubiprostone 24 mcg twice daily results 57% of the time in spontaneous bowel movement within 24 hours as compared to 37% for placebo.33 The major side effects of lubiprostone are nausea, diarrhea, headache, abdominal pain, flatulence, and vomiting. In clinical trials, lubiprostone 24 mcg twice daily was administered orally with food and water. Lubiprostone is approved for use in older adults and nursing home residents for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. In my experience, lubiprostone should be used when bulk, osmotic, and stimulant agents are not effective in the treatment of chronic constipation.

Lubiprostone is the latest medication to receive FDA approval for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. It activates the specific chloride channels (CIC-2) in the lining of the small intestine after oral administration, thereby increasing intestinal fluids. Lubiprostone 24 mcg twice daily results 57% of the time in spontaneous bowel movement within 24 hours as compared to 37% for placebo.33 The major side effects of lubiprostone are nausea, diarrhea, headache, abdominal pain, flatulence, and vomiting. In clinical trials, lubiprostone 24 mcg twice daily was administered orally with food and water. Lubiprostone is approved for use in older adults and nursing home residents for the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipation. In my experience, lubiprostone should be used when bulk, osmotic, and stimulant agents are not effective in the treatment of chronic constipation.

CONCLUSION

Constipation is a major problem in long-term care, and most of the data regarding constipation has been derived from other populations. Nevertheless, the impact of constipation is considerable in long-term care residents. This population includes persons with the highest frequency of risk factors, including immobility, polypharmacy, and chronic medical conditions. Constipation has a large impact on the quality of life for older persons and can lead to medical complications such as fecal impaction and incontinence. A careful history and structured differential diagnosis can result in significant improvement in conquering constipation in long-term care residents.

The author served on an advisory panel for Sucampo Pharmaceuticals, Inc, in 2006.