Critical Review of Transitional Care Between Nursing Homes and Emergency Departments

INTRODUCTION

Emergency departments (EDs) are major providers of nursing home (NH) residents. Urgent on-site physician evaluation, radiology and laboratory testing, and intravenous therapy, are not available in most NHs.1,2 As a result, NH residents who suffer acute illnesses or injuries are generally transported to an ED for evaluation and management. Indeed, each year nearly 25% of NH residents are transferred at least once to an ED.3

Transitional care has been defined as “a set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care within the same location.”4 Regrettably, healthcare settings, such as NHs and EDs, operate independently of one another, often providing care without the benefit of information from the other site of care.5-7 Poorly executed transitions are associated with inefficiencies and duplication of services that increase the cost of care and lead to greater utilization of health services.8 Most importantly, ineffective transitions put NH residents at considerable risk of receiving inappropriate or dangerous care.6

An NH resident travels a typical route during an episode of emergency care. There are five domains with intra-domain and inter-domain transitions:

1. NH domain before ED visit

2. Ambulance domain before ED visit

3. ED domain

4. Ambulance domain after ED visit

5. NH domain after ED visit

Intra-domain transitions occur during changes of shift, for example, when an emergency physician transfers care of the patient to the oncoming emergency physician at the end of his/her shift. Residents arrive at the ED domain through an NH-to-ED transition. The ED domain is then a branch point, where residents are admitted to the hospital, die in the ED, or are released back to the NH via an ED-to-NH transition.

NH residents are frequently seen in the ED and are a challenge to properly care for. Given these circumstances, we originally planned to conduct a systematic review of interventional studies that were designed to improve transitions between NHs and EDs. However, after encountering the paucity of interventional articles, we decided to critically review articles pertaining to transitions at the NH-ED interface. This review is focused on providing context and suggestions for future research.

METHODS

We defined “relevant article” as one that discussed, analyzed, or intervened in transitional care between NHs and EDs after the decision has been made to transfer the resident. A librarian with searching expertise and the authors independently searched for relevant English language articles in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and The Cochrane Library. Appropriate subject headings and text words were used, and the “exploding” technique was performed to maximize inclusion of all indexed articles.

As an example, our MEDLINE search strategy began with the following MeSH headings: “Nursing Homes” and “Long-Term Care,” which were combined using the Boolean search operator “OR.” The findings were combined using “AND” with the following terms: “Emergency Service, Hospital,” “Emergency Medicine,” “Emergency Medical Services,” “Emergency Treatment,” “Emergency Department,” “Emergency Room,” “Transportation of Patients,” “Patient Transfer,” or “Transitional Care.”

After each search, the titles and abstracts (if available) were read independently by the searchers to determine possible relevance to the study topic. Potentially relevant articles were then examined for relevance.

We used three other methods to identify relevant articles: (1) a hand search of the previous three years of issues in ten journals: Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging, Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, Gerontologist, Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, Annals of Emergency Medicine, Academic Emergency Medicine, American Journal of Emergency Medicine, and Journal of Emergency Medicine; (2) an electronic search of the ten journals’ databases using appropriate search terms; and (3) examination of references of all relevant articles.

We used qualitative methods to synthesize the literature and draw meaningful conclusions. A quantitative review of the literature was not appropriate because of the heterogeneity of the research in terms of study design and quality. Similar to Evidence-based Practice Centers at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, we took a “best-evidence” approach to capture available data, describe limitations, and suggest future research.9 To combine perspectives on each side of the NH-ED interface, the two authors (an emergency physician and a geriatrician) independently examined all articles.

RESULTS

Our MEDLINE search identified 850 articles. After reading titles and abstracts, 63 appeared relevant. Fourteen of the 63 were determined to be relevant after examining the full-text articles.2,3,10-21 The CINAHL search identified 322 articles. After reading titles and abstracts, 30 appeared relevant. Eight of the 30 were determined to be relevant after examining the full-text articles.10,11,13,18,21-24 Five of the eight were also found in MEDLINE.10,11,13,18,21 The Cochrane Library search generated 74 articles, but none appeared relevant when reading the title and abstract. The librarian’s searches did not identify additional relevant articles. The journal hand searches yielded four additional relevant articles.1,5,25,26 The electronic searches of journal databases identified no new relevant articles. We identified two additional articles in the references of relevant articles.27,28 In summary, we identified 23 relevant articles: one review article,27 three editorials,13,15, 26 eight descriptive studies,2,3,10,14,16-18,28 five qualitative investigations,1,5,11,20,24 and six interventional reports.12,19,21-23,25 The articles spanned 1983-2006 and included a total of 4961 transfers between 699 nursing facilities and 18 EDs.

Three themes emerged upon examining the articles: epidemiology of transitions, communication problems during transitions, and interventions to improve communication. Eight articles contributed to both the first and second topics, and 13 articles contributed to the third.

Epidemiology of Transitions

Nearly one-quarter of NH residents are seen in an ED at least once each year, and more than 10% are seen two or more times.3 The average age of NH residents seen in an ED is 76 years, with 83% over age 65 years.10 63% are full code,19 37-46% have a history of cognitive impairment,17,19 and two-thirds are acutely or chronically cognitively impaired at the time of the ED visit.14

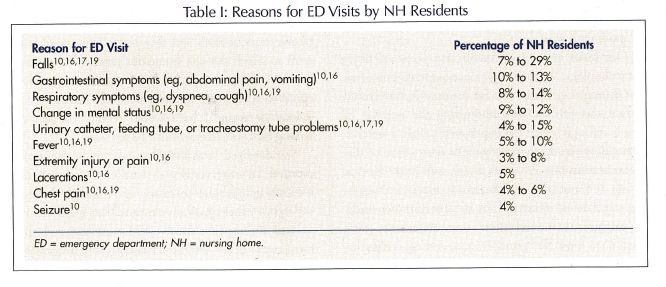

NH residents present to the ED for reasons that generally differ from those of older, community-dwelling individuals (Table I).14 However, according to survey1 and qualitative11 research, other factors (eg, resident preference, family request, familiarity of the NH physician with the staff and the resident) also influence decisions to transfer.

More than 70% of NH residents have testing performed in the ED.10 Blood tests are most common, but half have chest x-rays, and nearly half have electrocardiograms (EKGs). A large proportion also receives medications while in the ED. Forty percent are given parenteral medications, and 15% receive oral medications.10

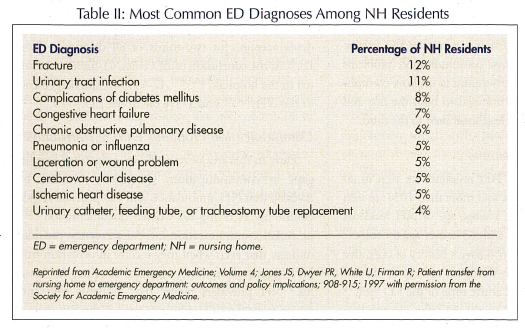

The ten most common ED diagnoses in NH residents account for two-thirds of all diagnoses (Table II).16 At the conclusion of ED visits, 41-52% are admitted to the hospital;3,10,16,17 42-54% are discharged back to the NH;3,10,16 and 1-5% die in the ED.3,10,16

Communication Problems During Transitions

Early in this area of research, investigators identified gaps in communication. Qualitative research has revealed that NH, ambulance, and ED providers report commonly receiving no written documentation5,22-24 or verbal communication.5,22,23 Emergency providers indicate that even when they receive information from NHs it generally is not in a form or at a time that is useful.5 NH providers report that residents frequently return from the ED without a copy of the ED chart or treatment recommendations.23 Observational research has substantiated many of these perceptions. Ten percent of NH residents are transferred to the ED without any written documents,16 and among the 90% that arrive with transfer paperwork, important information is still commonly missing.16,21,25,28

Providers witness many adverse consequences of poor communication, as the following examples illustrate.5 ED physicians feel as though they are working without adequate direction, information, or assistance from NH providers. According to ambulance personnel, poor communication of advance directives prevents uninformed providers from respecting the wishes of NH residents during respiratory failure, hypotension, or cardiac arrest. NH staff report that they cannot adequately care for residents or inform families after ED visits because of the sparse information they typically receive from EDs.

Interventions to Improve Communication

Several methods have been proposed to improve communication between NHs and EDs. In our research, focus group respondents proposed the use of audiotape cassette recorders, because it is more efficient to speak than write.5

Our focus group participants also proposed using fax technology.5 In their experience, paperwork is often lost during transitions, and fax communication would reduce this problem by minimizing the number of hands through which the paperwork travels. However, respondents in other investigations have come to different conclusions. Providers in one such study felt that faxing does not offer significant advantages over existing paper-based systems.20 In an observational study, investigators witnessed that faxed documents were illegible to most NH providers and, consequently, cautioned against use of fax.23

Information technology, which was not defined or exemplified, has also been proposed. A review article concluded that it has enormous potential for implementing innovative approaches to information transfer.27 However, focus group respondents have been less convinced of the advantages of information technology.20 Their trepidation results from the potential loss of confidentiality, the lack of equipment in the NH environment, and the generally technologically-naïve staff.

An intervention that was proposed in a recent editorial is the use of three-ring binders that contain information emergency providers need and are ready for transport.13 The stated advantage of the binder is the breadth of information that could be stored and shared with emergency providers. Many have advocated use of standardized transfer forms to improve communication.5,15,16,20,22,26 The reported advantage of standardized forms is that NH, ambulance, and ED providers would all receive a recognizable, concise form and they, accordingly, would not need to search through numerous pages of documents for essential information.5,20,26 A noted challenge is that efforts to develop and implement standardized forms on a local or regional basis would require cooperation among NH, ambulance, and ED providers.5,16

Standardized transfer forms have been implemented in interventional studies. Most of the research gauged the reactions of providers through surveys or other qualitative means after implementation of the transfer forms. NH staff reported that forms were easily completed during an emergency.12 Emergency physicians and nurses reported that the form made it easier to understand patients’ presenting problems, to find patients’ medications, and to care for patients.19 They also reported that the form expedited gathering information22 and seemed to save time.19,22 The most recent studies reported that the documentation of important clinical information increased significantly after introduction of the standard form,21 and information gaps occurred significantly less often when the transfer form was used.25 The problem is that after introduction of the forms, NH staff used the forms in only a minority of transfers to the ED.21,25 Even when the forms were used, much of the requested information was still not recorded19,21,25 and, in most cases, the exact reason for the ED visit remained either missing or unclear.22

DISCUSSION

Despite the large number of NH residents cared for in EDs, much remains to be understood about these vulnerable older adults and the emergency care they receive. The research examined in this review is an important starting point; however, a deeper understanding of the multiple, interactive factors involved in NH-ED transitional care is essential as the field moves toward interventional studies.

Only a limited amount of epidemiologic information has been published to date. Other than age, code status, and cognitive impairment, we know little about this group of vulnerable older adults, and much of the research is more than 15 years old. In addition to updates of earlier research, better information about additional characteristics such as comorbidities, medical histories, decision-making processes, and the influence of regulations and legal concerns on decisions would provide researchers with a richer understanding of NH-ED transitional care that will be required to design more effective interventions.

At this point, we cannot report whether residents receive high- or low-quality care during transitions. The primary problem is the lack of operational definitions for quality transitional care. Not only are operational definitions needed to assess the quality of care currently provided, but they will also be important when developing interventions and will operate as outcome measures in future interventional trials.

Another problem in the extant literature is the narrow focus of the research. Most studies examined a single site of care during a distinct point in time, such as the narrow window during which an NH resident is in an ED. ED visits are only one part of residents’ continuums of care. For this reason and because events in each setting affect others, researchers must have a fuller understanding of what occurs within each site of care.

Finally, the modest impact of seemingly promising interventions (eg, standardized transfer forms) may be a result of unique challenges to intervening at the NH-ED interface. First, the interface involves a collection of complex organizations with multiple agents within each system. Second, NH staffs, in particular, tend to have a high turnover rate, which affects intervention strategies.29 Third, NHs typically send residents to several different EDs, and EDs receive residents from numerous NHs. These obstacles indicate that developing partnerships with NH, ambulance, and ED providers to improve care jointly will be vital to implementing future interventions.27 Commitment and ownership shared by NH, ambulance, and ED staffs are critical factors to quality improvement.30-32

Recommendations for Future Research

Based on what is currently known, we recommend the following as next steps to improve transitional care.

1. More fully describe NH residents who are sent for ED care.

2. Document the outcomes of NH residents surrounding ED visits.

3. Record the processes of care (eg, medications administered, testing) provided to residents before, during, and after ED visits.

4. Define high-quality transitions of care using data from the three points above, as well as input from NH, ambulance, and ED providers.

5. Use the knowledge gained in the preceding steps to develop interventions to improve NH-ED transitional care.

6. Work cooperatively with NH, ambulance, and ED providers, as well as residents and families, if appropriate, to design, implement, and test interventions.

7. Where feasible, obtain the commitment and support of specific healthcare regions when testing promising interventions.

CONCLUSION

The limited success of seemingly promising interventions discourages the introduction of new strategies that may be expensive and further disruptive of care, and advocates fundamental work to examine the NH-ED interface more thoroughly. A more complete understanding of what actually happens before, during, and after ED visits by NH residents—and why—is necessary to inform researchers as we progress toward successful interventions.

Acknowledgments Dr. Terrell is supported by a Dennis W. Jahnigen Career Development Scholars Award, which is funded by the American Geriatrics Society, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc.