Challenges of Pain Assessment and Management in the Minority Elderly Population

Pain is a common syndrome many elderly patients experience.1 The prevalence of pain in older adults remains high. It is estimated that 25-40% of frail, community-dwelling elderly2 and 45-80% of nursing home residents suffer from uncontrolled pain.3 Little is known, however, about pain issues in minority elderly persons—non-Caucasian individuals over the age of 65 years. The topic demands attention considering the projected dramatic increase in the aging minority population over the next few decades.4 Based on the American Geriatrics Society’s ethnogeriatrics website, “The 2000 U.S. Census reflects an older adult population (age 65 and older) that is 84% Caucasian/white with 16% of the older population being Black/African American, American Indian/Alaska Natives, Asian and Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latino. It is projected that these percentages will change to …64% and 36% by 2050, respectively.”4

Minorities, primarily African Americans, American Indians, and Hispanics, are more likely than non-Hispanic whites to have chronic health problems, live in poverty, and lack insurance coverage.5,6 In 2002, the Institute of Medicine reported on the significance of racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare.7 While the current literature addresses many complications of unrelieved pain in the general elderly population and the benefits of pain control,1,3 there is a dearth of information regarding pain assessment and management in the minority geriatric population.8 This review will explore the existing literature on pain assessment and management in minority elders, including: current data on pain in the minority elderly population, physicians’ (in)ability to assess and treat pain in this subpopulation, and barriers and potential solutions to adequate pain management in minority elderly persons.

CURRENT DATA: NURSING HOME RESIDENTS AND COMMUNITY-DWELLING OLDER PERSONS

Nursing Home Residents

Two notable retrospective cohort studies utilizing the Systematic Assessment of Geriatric drug use via Epidemiology (SAGE) database examined pain assessment and treatment of minority elderly nursing home residents with cancer pain and noncancer pain. Bernabei et al9 evaluated data regarding 13,625 nursing home patients with cancer. The study revealed that patients from minority groups were less likely to have cancer pain recorded, relative to whites, and minority patients were more likely to receive NO analgesia. In African-American nursing home residents who did have daily pain recorded, there was a 63% increased probability of being untreated, relative to whites. Similar trends were observed for patients belonging to other minority groups (Hispanics, Asians, and Native American Indians).

Won et al10 reported data from the SAGE group database regarding noncancer pain: African-American nursing home residents with daily pain were at high risk for not receiving analgesia (odds ratio [OR], 1.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.4-2.05). A similar trend is seen for Hispanic nursing home residents. The data may actually represent a gross underestimation of pain because it is based on nursing reports, not patient self-report. The Minimum Data Set (MDS) constitutes a more than 350-item instrument that includes: sociographic information; numerous clinical items ranging from functional dependence to cognitive function; clinical diagnoses; and signs, symptoms, syndromes, and treatments being offered.9,10 Actual self-reports of pain are considered more accurate indicators of pain.11

Community-Dwelling Older Adults

There is a paucity of studies including community-dwelling minority elderly persons. An exhaustive literature search identified only a handful of original research on this topic. Andersen et al12 evaluated the prevalence of persistent knee pain among older adults, which revealed that 26.4% of Mexican-American women and 32.8% of African-American women reported knee pain, as compared with 22% of their Caucasian counterparts.

In the Health and Retirement Survey, Kramer et al13,14 interviewed 9802 subjects aged 51-61 years of age. Results indicated that 15.5% reported that pain made it difficult to do normal work, with the highest among American Indians (24.7%), Latinos (23.4%), and African Americans (19.3%), as compared with whites (14.4%) and Asians (14.2%). More Latinos (9.8%), African Americans (7.0%), and Asians (5.8%) described their usual pain as severe compared with whites (2%) or American Indians (2.0%). Ethnicity was a significant predictor of pain when controlled for age and gender.13,14

At the University of Michigan, Green et al15 analyzed a database of African-American and Caucasian patients over age 50 years with chronic pain who presented to a multidisciplinary pain center. Their findings are consistent with earlier studies: African Americans reported significantly more pain, suffering, and depressive symptoms. Another cluster analysis by Green et al16 revealed that older patients with good pain control reported lower level of pain and depression. These studies reinforce the belief that the benefits of pain control in the elderly are enormous: Effective pain management maintains older patients’ dignity, functional capacity, and overall quality of life.1

CHALLENGES OF ASSESSING PAIN IN THE MINORITY ELDERLY POPULATION

The precise nature of the relationship between aging and pain perception remains unclear.17 Furthermore, when the variations in interethnic attititudes toward pain are added to the mix, more uncertainty arises. Bates et al18 developed the biocultural model of pain perception that does not assume any basic difference in the neurophysiology of members of different minority groups. Rather, people learn in social communities, where conventional ways of interpreting, expressing, and responding to pain are acquired. The meaning of pain and suffering may be very different within different cultures.19 In one study evaluating ethnocultural influences on variation in chronic pain perception, Hispanics reported that they express their pain more frequently and emotionally and had significantly higher levels of interference with work and daily activities.18 However, in another qualitative study aimed at evaluating Hispanic cancer pain management, Juarez et al20 discovered that Hispanics were taught not to complain of pain from their childhood.

Kramer et al13,14 studied an American Indian subpopulation with chronic joint pain in urban Los Angeles to examine how American Indians understand and communicate their symptoms of chronic joint pain. Elderly American Indians (> age 62 years) more often chose to endure chronic pain. The studies revealed that American Indians used words such as “ache,” “pain,” and “discomfort” to describe pain of varying intensities ranging from mild to severe. The results suggest that an in-depth evaluation of the pain intensity and quality is warranted in these patients. There is significant discordance between the stereotypes versus data regarding American Indians and chronic pain; compare the stereotypes of stoic American Indians who do not express pain to the Health and Retirement Study that revealed that American Indians were more likely to report chronic pain compared with Caucasians.13,14

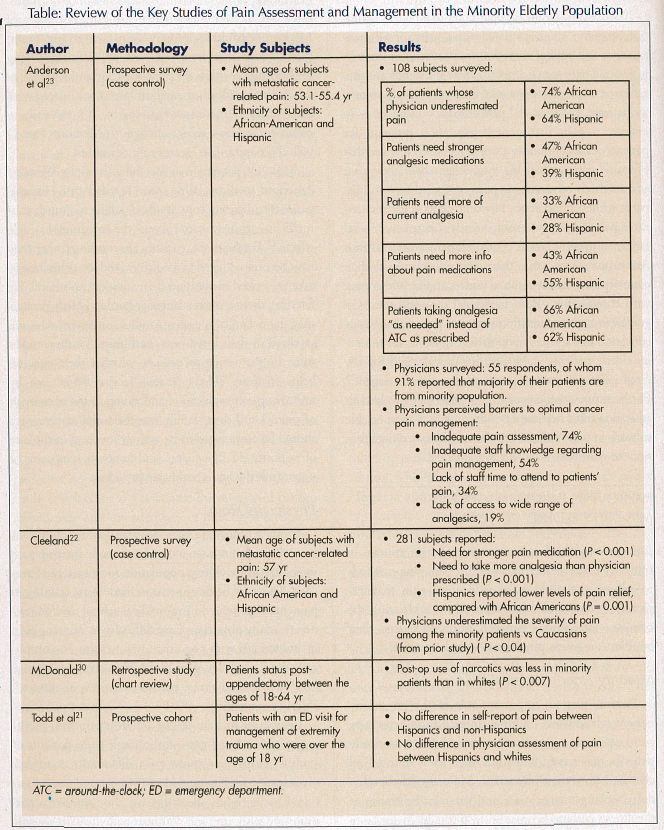

There are few studies in the literature examining how effectively physicians assess pain in minority patients. Furthermore, elderly patients were excluded from these studies. One study conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, (UCLA) emergency department compared physician assessment of pain in Hispanic patients and non-Hispanic whites with patients’ self-report of pain. The study revealed no difference in physicians’ ability to assess pain in non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics.21 However, two studies involving cancer minority patients produced conflicting results compared with the UCLA study. In the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) pain study, Cleeland et al22 evaluated the severity of cancer-related pain and the adequacy of prescribed analgesics in minority outpatients with cancer. Their data revealed that physicians underestimated the severity of pain in minority patients. In another oncologic study, Anderson et al23 discovered that physicians underestimated cancer pain severity for 64% of Hispanic patients and 74% of African-American patients.

These mixed results raise several issues. Were the emergency medicine physicians at UCLA more adept at assessing pain in Hispanics, as compared to ECOG physicians? While the UCLA study demonstrated no difference in ability to assess pain, the Hispanic patients received less pain medications than their white counterparts—18.8% versus 23.9%. Are physicians able to assess pain, but simply less interested in treating pain of Hispanics? Todd et al21 suggest that ethnicity may be a risk factor for “oligoanalgesia,” and the possibility that unless prompted, physicians are less likely to perform adequate or conscious pain assessment for minority patients, thus explaining the disparity in ordering analgesics for this subpopulation. Clearly, more studies need to be conducted to examine physicians’ ability to assess pain in the elderly minority population, as well as their knowledge of and attitudes about prescribing pain medicines in this population.

CHALLENGES OF TREATING PAIN IN THE MINORITY ELDERLY POPULATION

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Guideline on the Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons aims to help physicians assess pain in the elderly and to initiate both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment modalities.1 However, these guidelines do not specifically target the minority elderly population.

Pharmacologic Treatment of Pain

From a pharmacologic standpoint, Bernabei et al.9 clearly demonstrated the high prevalence of untreated cancer pain in the elderly population, and the minority elderly population. Other studies also reveal that minority patients are less likely to receive adequate pain control. The ECOG pain study polled 281 patients of Hispanic and non-white backgrounds with recurrent or metastatic cancer who were asked to rate their pain, how it interfered with function, and concerns they had about taking analgesics. Their physicians were also polled regarding the same topics. The results revealed 65% of minority patients versus 50% nonminority patients received inadequate analgesic treatment. Minority patients consistently reported they needed stronger pain meds and more analgesics than their physicians’ prescribed.22 Anderson et al23 performed a comparable survey and published similar results. They polled 108 African-American and Hispanic patients with metastatic or recurrent cancer and pain, and 55 of their physicians and nurses. Although the majority of patients received appropriate analgesics according to their physicians, 65% reported severe pain. Both Hispanics (28%) and African-Americans (31%) felt they received analgesics of insufficient strength.

Nonpharmacologic Treatment of Pain

The AGS guideline on pain notes that patient education programs, those associated with practice of self-management and coping strategies, are successful in improving overall pain management.1 There is a significant gap, however, in the effectiveness of these programs in minority patients. Juarez et al24 performed a nursing study to evaluate a pain management education program for patients of select minority groups. The study revealed that Hispanic patients had less knowledge about their pain and methods of managing pain compared to non-Hispanic whites. In addition, Hispanic patients experienced more pain distress, and subsequently suffered more total family distress. Overall, both Hispanics and African Americans scored worse than their non-Hispanic white counterparts when it came to understanding and coping with chronic pain. Both traditional data and the AGS guidelines support the effectiveness of pain management education in the elderly population; however, for minority elderly patients, culturally, linguistically and age-tailored education materials still need to be developed.25 Furthermore, competency training for staff involved in education must become a priority, and they must be able to work in partnership with community-based organizations to effectively reach out to individuals.

IMPROVING PAIN MANAGEMENT IN MINORITY ELDERLY PERSONS

Enumerating the barriers to optimal pain control in minority elders is the first step in developing methods to address the problem of inadequate pain management. Potential solutions depend on addressing the complex interactions between minority elders, their families/caregivers, physicians, and pharmacies.

Minority Elderly Patients’ Role

Patients play an important role in the physician– patient relationship. Cultural differences in expressing pain represent a significant barrier, because minority patients may attempt to hide their pain if they feel alienated from their physicians. Minority elderly often delay seeking medical care until later in the course of the illness, perhaps because of the difficulty in accessing healthcare as a result of their socioeconomic status. Green et al26 surveyed patients at the University of Michigan’s Multidisciplinary Pain Center and found that Caucasian patients reported less difficulty paying for healthcare within the previous 12 months, as well as less difficulty affording medical care, as compared with their African-American counterparts. It is too early to comment on how recent changes to Medicare Part D will affect minorities’ access to medications.

Minority patients may be dubious about Western/ American medicine. One study revealed that Hispanic patients had greater concern about taking too much pain medicine, and worried about the medications’ side effects.22 Furthermore, patients are concerned that they may become addicted to medicines, and so are hesitant to take prescribed medication.27 In addition to cultural differences, there is often a language barrier. Elderly persons may have family members and/or caregivers who are involved in their loved ones’ healthcare. Further studies must be performed to evaluate whether their presence helps minority elderly persons receive better care by improving communication and aiding in the assessment of pain. Until then, family members and/or caregivers should be encouraged to be actively involved in the care of minority elderly patients, and to report symptoms of uncontrolled pain to healthcare providers.

Physicians’ Role

From a healthcare provider standpoint, physicians have difficulty in assessing and optimally treating pain in the minority elderly population for a variety of reasons. This may be due in part to inadequate training in pain management during medical school and/or residency. Many physicians have difficulty in assessing pain in individuals with cognitive dysfunction. To complicate the knowledge gap, many physicians are unsure how to start and titrate pain medications in the frail, elderly population.

Couple the inability to rate and treat pain with another gap: the cultural gap—for example, how patients of various ethnicities express pain differently. A further investigation on how providers’ own cultural and educational backgrounds affect the way they perceive, communicate with, care for, and treat patients with chronic pain must be performed.28 Psychiatrist and medical anthropologist Arthur Kleinman described the “culture of biomedicine,” a distinct culture physicians adopt during their training in Western medicine.28 He remarks, “If you can’t see that your own culture has its own set of interests, emotions, and biases, how can you expect to deal successfully with someone else’s culture?”28

Sociologist Dr. Renee Fox asks the important question of whether medical schools are truly capable of teaching cultural competency, or whether it should be an undergraduate prerequisite for medical school applicants.28 Until those theories are more clearly defined, healthcare providers and healthcare trainees need understand that the gap exists and has implications on disparities in healthcare for minority elderly persons. They can utilize resources such as the Stanford Curriculum in Ethnogeriatrics website, which has ethnic-specific information: https://www.stanford.edu/group/ethnoger/.

Furthermore, issues of cultural competency and pain management must be woven directly into the curriculum in medical school and residency training programs. Formal testing in standardized exams (United States Medical Licensing Exam, Specialty Boards, and Recertification Boards) would aid in reinforcement of these concepts. Modeling is another way to instill these skills; physicians-in-training must have exposure to mentors who have competency in addressing pain in the minority elderly population.

In addition to the knowledge and cultural gaps, prescribing narcotics in certain states requires triplicate prescriptions. Von Roenn et al25 suggest that these physicians tend to prescribe narcotics less frequently than physicians from non–triplicate-requiring states—in other words, the “triplicate theory.” Advancing this theory one step further, are physicians concerned about prescribing narcotics to minority elderly persons who report that they live with relatives involved with buying, selling, and/or using illicit drugs?

Finally, add the communication gap. Two more barriers to adequate pain management are physicians not having adequate interpreter services at their site of providing care6 and the stress of time required to address communications difficulties. Physicians and nurses may feel (either knowingly or unknowingly) that they lack time to effectively address these patients’ pain issues when communication is already a challenge.

Pharmacies’ Role

Even if physicians prescribe analgesia to their minority elderly patients experiencing pain, the patients may not be able to obtain the medications from their neighborhood. Morrison et al29 performed a prospective cohort study to determine the availability of commonly prescribed opioids in five boroughs in New York City. Based on the U.S. Census, they determined the ethnic predominance and crime rates in the neighborhoods of the randomly selected pharmacies. Their study revealed that 66% of pharmacies that had no opioid supplies were in predominantly non-white neighborhoods (< 40% white). Only 25% of pharmacies in predominantly non-white neighborhoods had adequate opioid supplies, as compared with 72% of pharmacies in predominantly white neighborhoods (> 80% white). Pharmacists polled (who did not have adequate opioid supplies) reported a variety of explanations: 54% reported they had little demand for these medications; 44% cited concern about disposal; 20% cited fear of fraud or illicit drug use that may result in a Drug Enforcement Agency investigation; and 19% cited fear of robbery. The inability to obtain analgesic medications represents one form of an access to care issue that minority elderly patients face.

There is no doubt that pharmacies need to expand availability of standard analgesic medications (per World Health Organization classification) equally in white and non-white neighborhood pharmacies. Pharmaceutical companies should be encouraged to develop patient-assistance programs to help defray costs of expensive opioids for minority elderly patients who are unable to afford these medications.

CONCLUSIONS

As both the geriatric and minority populations boom over the ensuing decades, the issues of pain assessment and management in minority elderly persons will need to be addressed. Physicians, other healthcare providers, patients, and their caregivers must work together to improve quality of life for minority elderly persons in the United States.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.