The Older Patient with Type 2 Diabetes: Special Considerations and Management with Insulin

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a disease that is increasingly prevalent among the aging adult population. In the United States, it is estimated that at least 18% of people age 60 years and older have the disease (diagnosed and undiagnosed), with most (90%) classified as type 2 DM (T2DM).1 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have reported that from 1980 through 2002, there was an increase in the prevalence of diabetes in all age groups (Figure).2 The highest prevalence, however, was found among older persons. Comparison of age groups reveals striking differences: In 2002, the prevalence of diabetes among people age 65-74 years (16.8%), was nearly 14 times that of people younger than age 45 years (1.2%).

Elderly patients often may be unaware of impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes because common symptoms of hyperglycemia may be absent. Atypical presentation of disease is common, especially with advanced age, and may include nonspecific lethargy, functional decline, weakness, and even confusion. In view of the considerably increased risk for T2DM with older age, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends that screening for diabetes every 3 years should be considered for all individuals age 45 or older, particularly for those with a body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m2 or higher. The criteria for diagnosis of diabetes in adults are provided in Table I.3

This review will examine the need for glycemic control in elderly patients with T2DM, and discuss the implications for initiation of insulin in this population.

GOALS GOVERNED BY QUALITY OF LIFE: INDIVIDUALIZATION OF TREATMENT IN OLDER PATIENTS

Overall Goals

The overall goals for treatment of hyperglycemia in older patients are essentially the same as those for younger patients with T2DM. These include achieving and maintaining glycemic control, as well as decreasing the risk of complications (microvascular and macrovascular) associated with diabetes.3,4 Not all older individuals may benefit, however, from the aggressive pursuit of glycemic control. Thus, the relative advantages of strict adherence to glycemic goals (intensive therapy) should be considered in the context of possible risks, such as hypoglycemia. This is particularly relevant in the older patient with complications of long-standing diabetes, such as nephropathy, retinopathy, or evidence of cardiovascular disease (eg, stroke and/or peripheral vascular disease). Elderly patients with diabetes who are in generally poor health, such as those in nursing home care, may be likely to have end-stage disease manifestations that could preclude an intensive approach to therapy.

Patient Level of Functioning and Individualization of Glycemic Goals

Older patients with a high level of functioning and better general health status may benefit greatly from intensive glycemic control, including prevention or delay of complications associated with diabetes. Conversely, an older patient with diabetes and poor functional status may not obtain the benefits from such a regimen. Functional status may be affected by geriatric syndromes (depression, dementia [associated with decreased thirst and appetite, and therefore greater risk for hypoglycemia], incontinence, cognitive impairment, chronic pain, and injurious falls) and polypharmacy, which are more common in patients with diabetes.5,6

Setting Glycemic Goals According to Patient Type

The variability in functional status among older patients with diabetes has practical implications: Healthy elderly patients with good functional status should target A1C levels of 7.0% or lower, which is the same A1C level recommended by the ADA for healthy adults of all ages with diabetes.3,4 Typically, this type of patient will be active, able to exercise, show little or no signs of cognitive impairment, and, due to an expected longer life expectancy, would be postulated to gain long-term benefits from sustained glycemic control.

In older patients with low functional status, cardiovascular and mortality outcomes have been shown to be similar for those with or without diabetes. Accordingly, quality-of-life considerations should take precedence in setting glycemic goals for these individuals with diabetes.7 This category would include patients who are considered frail, those with a life expectancy of less than 5 years, or individuals who present with any condition or comorbidity indicating that the risks of glycemic control would outweigh the benefits.4,8 In this patient population, treatment with less intensive regimens would be preferred, because intensive glycemic control would not provide a significant clinical advantage.4 For frail elderly patients who have comorbid conditions with T2DM, a less optimal A1C target of 8.0% or lower may be considered appropriate.4,9 However, a less than optimal A1C target must be balanced against the risk associated with acute hyperglycemic emergencies. Thus, although individualizing treatment goals may permit setting of less rigorous glycemic goals for some individuals, consideration must remain for prevention of hyperglycemic complications, particularly the hyperosmolar states.

For elderly patients with diabetes with generally good health, however, intensive therapy can be implemented with little more risk consideration than would be given for younger patients with diabetes. A recent study compared a multiple daily injection (MDI) regimen to continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion (CSII), specifically in elderly patients with T2DM (mean age, 66 ±5.9 years). Patients were excluded from the study if severe impairment of cardiac, renal, or hepatic function was present. Treatment satisfaction improved significantly with CSII and MDI (P < 0.0001), and the difference between groups was not statistically significant. Moreover, mean A1C fell by 1.7% ± 1.0% to 6.6% in the CSII group and by 1.6% ± 1.2% to 6.4% in the MDI group, levels well below the ADA recommended goal of 7.0%. Neither the difference in A1C nor the incidence of hypoglycemia between treatment groups was statistically significant. This study demonstrates that pursuit of strict glycemic control using CSII or MDI can be successfully implemented with good safety and patient satisfaction in reasonably healthy older individuals with T2DM. 10

BENEFITS OF GLYCEMIC CONTROL:CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE OLDER PATIENT

Preventing Acute Complications of Hyperglycemia

Attaining glycemic control to reduce acute complications associated with diabetes is a priority for all elderly patients. Hyperglycemic complications include dehydration, mental status changes, increased risk of infection, and, in severe cases, the possibility of hyperosmolar coma, a condition more often fatal in the elderly.11 Complications of inadequately controlled blood sugar levels in the long-term care setting include slow healing, as in the case of pressure ulcers. Thus, prevention of hyperosmolar states, infection, and other complications by maintaining serum glucose levels within recommended parameters is of particular concern in older patients.12,13 Although flexibility may be allowed in setting glycemic parameters for individual treatment goals, the clinician also must take into account the need to prevent associated acute complications.4

Preventing or Delaying Long-Term Complications of Diabetes Through Tight Glycemic Control

The benefits of glycemic control have been clearly established in landmark clinical trials, such as the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) and the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, as well as other studies in adult patients.14-19 Results from the UKPDS determined that the complication-free interval for newly diagnosed patients with T2DM on conventional (nonintensive) therapy was 12.7 years. The complication-free interval was defined as the point in time reached when 50% of patients in a therapy group had developed at least one diabetes-related (microvascular or macrovascular) complication. Accordingly, one could expect a similar time interval for complications to develop in older patients with T2DM who are not treated intensively for glycemic control.

Microvascular Complications

Intensive glycemic control, achieved through the use of insulin in combination with diet and exercise modification and/or oral medications, decreased the risk or slowed development of microvascular complications, including retinopathy and nephropathy. Furthermore, an epidemiologic analysis of the UKPDS projected that for every 1% reduction in A1C, there was a corresponding 35% reduction in microvascular complications, and a 25% reduction in diabetes-related mortality.14

The risk for sensory neuropathy, another sequela of poor glycemic control, also can be reduced through better control of blood glucose.16 Peripheral neuropathy may increase the risk for falls; thus, elderly patients with diabetes may benefit indirectly from glycemic control in terms of potential fall risk reduction.20 Prevention of nephropathy is another prominent goal in elderly patients because renal disease in older patients with diabetes is associated with increased mortality as compared with age-matched patients who do not have renal impairment.21

In all, the progressive course of T2DM underscores the importance of glycemic control for prevention, delay, or, at minimum, slowed progression of microvascular complications in elderly patients diagnosed with diabetes.

Macrovascular Complications

Cardiovascular disease is 2-4 times more prevalent among individuals with diabetes than in the general population and is the leading cause of death in patients with diabetes.1 Glycemic control may decrease the risk of cardiovascular events and stroke, especially when integrated into an intensive multifactorial approach that includes behavior modification and pharmacologic therapy for hypertension, dyslipidemia, and microalbuminuria.14,22 Intervention to obtain glycemic control in the prediabetic stages of T2DM is essential because the risk for cardiovascular disease can be substantially elevated even before a clinical diagnosis of chronic hyperglycemia is made.23 Recently, it was shown that intensive insulin therapy, compared with conventional regimens, significantly reduced the risk of any cardiovascular disease event by 42% (95% confidence interval [CI], 9-63%; P = 0.02) and the risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from cardiovascular disease by 57% (95% CI, 12-79%; P = 0.02) in patients with T1DM. Many elderly patients, when health status and life expectancy permit, could also be expected to benefit from the long-term cardiovascular risk reduction observed with intensive therapy in this study.24

Other Possible Benefits of Glycemic Control

In addition to preventing or delaying microvascular and macrovascular complications, there is evidence that improving glycemic control results in better cognition in older individuals with T2DM. Ryan and colleagues25 recently examined the effects of addition of glyburide or rosiglitazone to ongoing metformin therapy on cognition in 145 older (mean age, 60 yr) T2DM patients without dementia. After 24 weeks, similar and significant improvements in fasting plasma glucose (FPG) from baseline were observed in both treatment groups (2.1-2.3 mmol/L). The reductions in FPG with either treatment were found to be associated with improvements in working memory (P < 0.0001 for rosiglitazone; P < 0.001 for glyburide), as measured by the Paired Associates Learning Test from the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery. Although further study is needed, and it is unknown whether reducing hyperglycemia is directly responsible for the observed improvements, these results indicate that glycemic control may confer benefits that could improve the cognitive dysfunction associated with diabetes in older individuals.26

Adults with Diabetes, Including Older Patients, Are Not Reaching Recommended Glycemic Targets

A recent analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) reported that only 37% of adults with diabetes are meeting recommended glycemic goals of A1C lower than 7.0%.27 A previous report from NHANES III demonstrated the following: of patients age 65 years and older on insulin therapy, only 27% achieved an A1C lower than 7.0%.28 It is evident that despite the abundance of therapeutic options for T2DM, older adults are not receiving adequate antihyperglycemic treatment to avoid complications of diabetes.

INSULIN THERAPY IN OLDER PATIENTS WITH T2DM

Analysis of Risks and Benefits

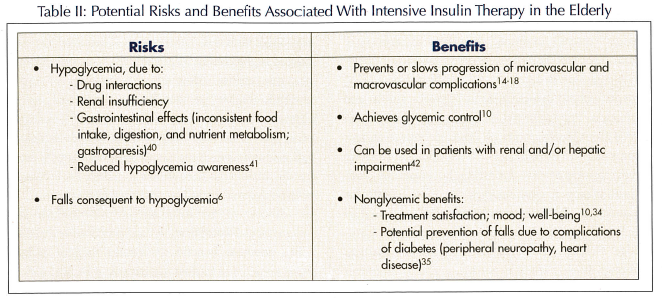

When treating with insulin, the clinician must address whether risk or benefit to the patient would be more likely as a result of intensive insulin therapy.4 Insulin has proven to be a very effective and flexible therapy, allowing patients to achieve glycemic goals, as there is no maximum dose, and glycemic control is achievable with sufficient titration. This should be considered in the context of possible risks, including hypoglycemic events. Although the majority of hypoglycemic events are not serious, increased age is correlated with incidence of severe events.29 Predictors of hypoglycemia in elderly patients include advanced age, recent hospitalization, and polypharmacy.30 Use of insulin analogs has been shown to reduce the incidence of hypoglycemia, including nocturnal hypoglycemia.31-33 In addition to the reduction of microvascular and macrovascular complications associated with diabetes, other potential benefits of insulin therapy include improvements in patient assessment of health, patient treatment satisfaction, and decreased risk of injurious falls.34,35 A list of potential risks and benefits of insulin therapy is provided in Table II.

Timely Intensification of Therapy with Insulin

T2DM is a disease of progressive insulin secretory dysfunction. If glycemic control is initially achieved with oral agents alone, it cannot be maintained over the lifetime of the patient with substantial life expectancy. Although initial therapy for most adult patients with T2DM includes diet and lifestyle interventions alone or combined with oral therapy, management of T2DM should include progressive treatment intensification when glycemic goals are not met in a timely manner.3 Continuous monitoring and treatment titration should be conducted in order to prevent an inadequate response to oral therapy to go undetected for extended periods of time. This approach can avoid unnecessary delays in advancement of therapy and is particularly important for those patients with A1C levels higher than 10.0%. The Road Map for Prevention and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes, recently issued by a joint task force from the American College of Endocrinology (ACE) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE), recommends persistent titration of oral combination or monotherapy therapy for a maximum period of 2-3 months before advancing to intensified regimens, including initiation of insulin therapy.36

In response to concerns about the practicability of patients with diabetes achieving glycemic targets, ACE, in a position statement issued by the Implementation Conference for ACE Outpatient Diabetes Mellitus Consensus Conference, cited the need for insulin in combination with oral agents.37 The consensus statement emphasizes that insulin, in combination with oral agents or when used in basal-prandial regimens (basal insulin therapy plus mealtime insulin injections), should be administered early in the course of T2DM to reach or sustain glycemic control, and also emphasizes that timely introduction of insulin can preclude further development of complications already in progress.

Elderly patients with T2DM may be more likely to be in an advanced stage of diabetes than younger patients, simply due to a longer duration of disease and progression of β-cell failure. In more advanced cases of diabetes, adequate control may not be achieved without the administration of insulin. A recent study of 7893 patients, performed in a predominantly primary care setting, demonstrated that significant improvement in glycemic control in patients with T2DM can be achieved by adding insulin glargine to existing oral therapy. A subgroup analysis of patients stratified by age younger than 65 years or 65 and older showed that that this effect was independent of age.38 Control of fasting and postprandial glucose levels in older adults can also be achieved by providing basal-prandial insulin replacement in MDI regimens that approximate a physiologic insulin profile.10 By providing basal blood glucose level control and preventing post-prandial blood glucose excursions, MDI regimens provide a therapeutic option for preventing or delaying chronic complications of diabetes, slowing disease progression, and possibly preserving β-cell function.14

Many older patients with T2DM who possess a generally good health status can benefit from persistent and stepwise intensification of therapy, including initiation of insulin, as recommended by the ACE/AACE Diabetes Roadmap Task Force.36 For frail patients, however, such as those in long-term care with long-standing complications of diabetes, comprehensive management and prevention may be impractical. In the elderly with poor overall health, consideration should be given to quality-of-life measures.

Initiating Insulin Therapy

Initiating insulin therapy can be accomplished by using simple, stepwise titration algorithms that are easy for patients to follow. A recent study tested a weekly forced-titration algorithm based on fasting blood glucose values in patients with T2DM who were unable to reach glycemic goals on oral antidiabetic therapy alone.32 Pre-study oral agents combined with systematic titration of once-daily bedtime basal insulin glargine (mean patient age, 55 ± 9.5 yr) or neutral protamine Hagedorn (NPH) insulin (mean patient age, 56 ± 8.9 yr) achieved recommended glycemic goals of lower than 7.0% in the majority of patients. Patients taking insulin glargine, however, met glycemic targets with significantly less nocturnal hypoglycemia than patients taking NPH insulin. This may be of particular concern for elderly patients who live alone and/or who are at risk for falls and fall-related fracture. The forced titration algorithm was an effective approach but may not be appropriate for all patients. An alternative and similarly effective dosing strategy implemented in recent large clinical trials increased the basal insulin dose by 2 units every 3 days until a fasting plasma glucose level of lower than 100 mg/dL was obtained (mean patient age, 57.5 ± 10.0 yr).39 This titration resulted in significantly greater reduction in A1C than did less frequent, visit-based titrations (P < 0.001), and thus may provide an effective approach to basal insulin therapy for elderly patients with T2DM.39

SUMMARY

The elderly patient with diabetes represents a unique challenge to caregivers. Therapy must be individualized, and careful consideration should be given to the patient’s existing comorbidities, life expectancy, and functional status. For patients with higher functional status and substantial life expectancy, intensive therapeutic options may be appropriate. Guidelines provided for geriatric patients with diabetes emphasize that older patients with relatively good health status can gain many of the same benefits from tight glycemic control obtained by their younger counterparts. Prevention and management of cardiovascular risk factors may be integrated in a multifactorial intensive approach, along with appropriate treatment for common geriatric syndromes. Insulin therapy is often appropriate for many patients, and may be effectively initiated with a basal insulin, and then advanced to basal-prandial insulin replacement if needed. Further studies are needed in geriatric patients to establish optimal treatment regimens for this growing segment of the population.

Dr. Charles Cefalu reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. William Cefalu has served on the advisory boards of Pfizer Inc, Merck and Co., Inc, Eli Lilly and Company, and Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and has received research support from Pfizer Inc, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novo-Nordisk.