Asymptomatic Bacteriuria in the Nursing Home

DEFINITION OF ASYMPTOMATIC BACTERIURIA

A positive urine culture does not prove that a patient has a urinary tract infection (UTI). The term asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is used to suggest that a patient has bacteria in the urine but not a true infection; a true UTI is bacteriuria in association with specific symptoms arising from the urinary tract. Women without urinary tract symptoms but with two consecutive urine cultures containing 100,000 colony-forming units per milliliter (cfu/mL) of a single isolate, obtained by clean catch of a voided specimen, have, by definition, ASB. ASB in men is defined in a similar way, except that only one urine culture with 100,000 cfu/mL of a single organism is needed to meet the definition. A catheter specimen from asymptomatic men or women that grows 100 cfu/mL also meets the definition of ASB. Patients without urinary tract symptoms but with significant bacteria in their urine have ASB and not a UTI.

PREVALENCE OF ASB

The elderly, especially those residing in long-term-care facilities, more commonly have ASB than the general population. About 25-50% of women and 15-40% of men living in long-term-care facilities have ASB.1 The prevalence rates in elderly women and men outside of the nursing home are 10.8-16% and 3.6-19%, respectively.1 The high prevalence among nursing home residents presents a particular problem since ASB resembles UTI on paper, but treatment of ASB is unnecessary. Clinicians caring for long-term-care residents need to be able to recognize ASB and distinguish it from UTI, especially as the number of elderly people residing in nursing homes increases. From 1990 to 2030, the nursing home census in the United States for those older than 65 is predicted to double.2 Recognizing that ASB is common among residents living in long-term-care facilities, and that it is an entity separate from UTI, will improve patient care.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY OF ASB

Many conditions common to the elderly, and even moreso those in the nursing home, contribute to dysfunction of the urinary system and ASB. Bacteria gain access to the urinary tract by the ascending route from the perineum. Most people are able to eliminate these bacteria with the first line of defense, flow of urine, but this defense is weaker in those with ASB. Aging, physical impairment, and mental decline, including dementia, lead to the development of ASB, most likely by resulting in incomplete bladder emptying.3-7 Other conditions common to the elderly, such as prostate enlargement and bladder prolapse, are associated with limitations to flow of urine, and possibly to ASB. Abnormalities unrelated to urine flow but consistent with functional decline, such as decreased prostatic secretions and inability to acidify the urine, have also been suggested in the pathophysiology of ASB. Additionally, estrogen deficiency enhances colonization of the vaginal introitus and has been proposed as a potential risk factor for ASB. Since these conditions are commonly encountered in the nursing home, it is easy to see why ASB is so prevalent in this setting.

The actual place of residence may be a risk factor for ASB as well. One would expect to find residents with poorer function in nursing homes; an analysis of three groups of ambulatory elderly women living in the same retirement community demonstrated that bacteriuria was related to where they lived. These women resided in either an independent living site, an apartment-type assisted living building, or the nursing home. With increasing level of care, a successive increase in ASB prevalence was noted.8 Living in a nursing home more than doubles the chance of developing ASB, as seen in the prevalence data.

TREATMENT OF ASB IS UNNECESSARY

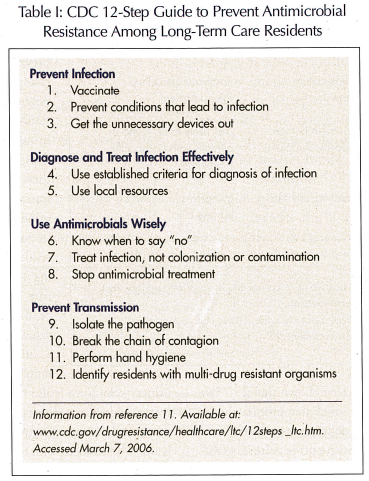

Morbidity and mortality are unchanged in long-term care patients with ASB, with or without treatment.1,3-5 Antibiotics do not alter the course of ASB, and bacteria will only temporarily be eliminated. There is a high recurrence rate of bacteriuria after antimicrobial prescriptions.4,5,9,10 Some clinicians may have a lower threshold for treating residents in the nursing home because of beliefs that they are sicker in general, but this is not justified when considering ASB. There is no difference in the mortality rates of people with ASB living in nursing homes compared with the mortality rates of those with ASB living outside of nursing homes.4 Among the three groups of patients living in three different settings within a retirement community discussed above, those who never had a positive urine culture and those who were considered “ever positive” for bacteriuria had similar death rates.5 Additionally, further functional decline, renal failure, and increased symptomatic infections do not result from ASB.4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) agree that treating ASB in nursing home residents will do more harm than good. A 12-step guide from the CDC for reducing antimicrobial resistance in nursing homes (Table I) includes a provision for avoiding use of antibiotics in situations of bacterial colonization, including ASB.11

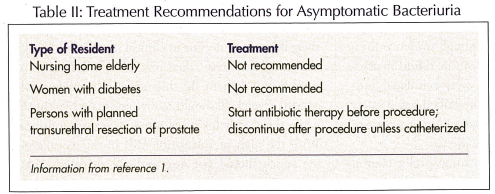

The literature does not specifically address residents with diabetes living in long-term care facilities, but treatment of ASB is not recommended for persons with diabetes in general.1 Hyperglycemia and diabetes alter the immune response, and although persons with diabetes do develop UTIs more frequently, ASB is not a risk factor leading to symptomatic infections.10 This is true for the postmenopausal woman with diabetes, as well.12 As with others with ASB, the individual with diabetes does not have an increase in renal complications.6,13 Merely finding abnormal urine in the nursing home resident, including those with diabetes, should not prompt therapy if symptoms are absent.

One indication does exist for treatment of nursing home residents with ASB. Antibiotic therapy to temporarily eliminate bacteria will reduce complications associated with procedures involving manipulation of the urinary tract. Patients scheduled to undergo transurethral prostate resection, or other invasive procedures that are associated with mucosal disruption and bleeding, should have antibiotic therapy initiated before the procedure and continued after the procedure if a catheter remains in place.1 Treatment recommendations are listed in Table II.

PREVENTION OF ASB IS UNNECESSARY

If treatment is unnecessary, then attempts to prevent ASB are also not warranted. Little can be done to prevent a UTI in nursing home residents,14 and this would be true for ASB as well. Good perineal hygiene and frequent bladder emptying may be beneficial for other reasons; however, without evidence of ASB changing the person’s prognosis, a strict regimen does not need to be initiated for ASB prevention. Some medications may alter bladder function, but there is no conclusive evidence that they contribute to the development of ASB. Analgesics, cardiac drugs, antihypertensives, antimicrobials, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidiabetic agents, and medications with anticholinergic side effects were not found to have a statistically significant relationship to ASB.15,16 Although some have proposed estrogen deficiency and inability to acidify the urine as risk factors for developing ASB, there is not adequate evidence for recommending use of estrogen, topical or oral, or cranberry juice for prophylaxis.4,7,14,17 Preventive measures are not necessary, and since prevention and treatment are ineffective, routine screening of nursing home residents is also not recommended.

DISTINGUISHING ASB FROM UTI

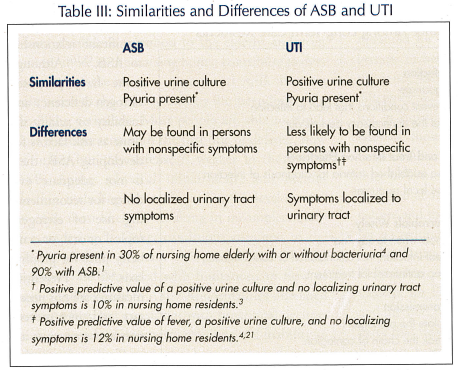

The challenge for the clinician is not in deciding whether to treat the nursing home resident with ASB, but rather in distinguishing ASB from UTI. The most reliable indicator of a true UTI in long-term care residents is symptoms specifically arising from the urinary tract, such as flank pain, dysuria, urinary frequency, or any combination of these, and not just an abnormal urinalysis, a positive urine culture, or nonspecific clinical changes. Table III demonstrates the similarities and differences of ASB and UTI.

ASB causes abnormal urine tests that mimic UTI, which entices clinicians to initiate therapy believing that they are treating UTI. Nicolle et al18 have shown that 25-75% of the time antibiotics are used inappropriately in nursing home residents. By definition, both residents with ASB and UTI have a positive urine culture, so the finding of an abnormal culture alone is not adequate to start therapy. In addition, since ASB does not go unnoticed by an individual’s immune system, there are inflammatory markers present in the serum and the urine of these residents.9,19 This includes the presence of white blood cells in the urine, or pyuria. Ninety percent of residents in the nursing home with ASB will have pyuria.1 In addition to those with ASB having this abnormal finding on urinalysis, 30% of nursing home residents will have pyuria without bacteriuria.4 The absence of pyuria is a good predictor that UTI is not present, with a negative predictive value of 80-90%.4 Pyuria alone is not enough evidence for a treatable infection, since pyuria can be found in association with both UTI and ASB, or as an isolated finding. Antibiotics should not be prescribed based solely on the finding of an abnormal urinalysis or a positive urine culture in nursing home residents.

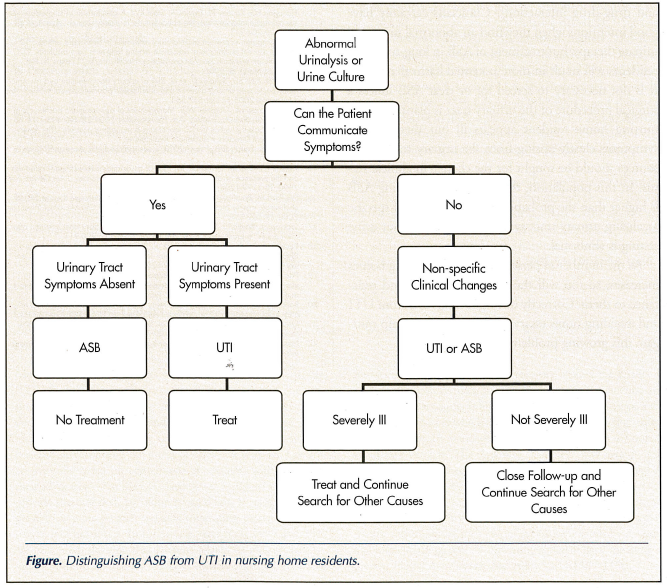

A nursing home resident with a nonspecific clinical status change who can communicate that he or she does not have localizing urinary tract symptoms will most likely not have UTI. With the high prevalence of ASB in this group, a change in chronic symptoms or new acute symptoms (eg, mental status change, weakness, change in appetite, nausea, vomiting) does not accurately predict UTI if there are no urinary tract symptoms.3,14 This is true even if a urine culture is positive. A positive urine culture in nursing home residents who do not have localizing symptoms will not represent true urinary tract infection 90% of the time (positive predictive value, 10%).3 Attributing fever to a urinary infection in nursing home residents without specific urinary symptoms is also fraught with error. The elderly may or may not develop a robust febrile response to any infection, but with advanced infections they usually do.4,20 A resident with fever and a positive urine culture, but not localizing urinary symptoms, will have a UTI only 12% of the time (positive predictive value, 12%).4,21 The fever is more likely to be from another source in these residents. UTI is clearly present when abnormal urine testing exists along with symptoms arising specifically from the urinary tract. Otherwise, abnormal urine tests coupled with nonspecific symptoms signal ASB.

Differentiating UTI and ASB is difficult in nursing home residents who cannot clearly articulate their symptoms. If a resident cannot communicate whether he or she has localizing urinary tract symptoms, and there is a general decline in clinical status in addition to abnormal urine tests, then physicians will have to use their best judgment. In this scenario, a resident who appears severely ill should receive antimicrobial therapy while the search for a definitive diagnosis continues. With the high prevalence of ASB in this population, the search should not stop with the urinalysis. Close observation and frequent follow-up is appropriate for those with nonspecific symptoms and abnormal urine, when not severely ill.

The Figure illustrates an algorithmic approach to aid in distinguishing ASB from UTI.

IMPORTANCE OF NOT TREATING ASB

As mentioned, differentiating the two entities is particularly important because treatment of ASB will do more harm than good. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics continues to escalate in part because of their overuse in long-term care facilities. During any 12-month period of residence in a nursing home, 50-70% of residents will receive at least one course of antimicrobial therapy.18 Most often, these prescriptions are for a supposed infection of the urinary tract. As many as three out of four are unnecessary. Gram-negative enteric organisms are now demonstrating resistance to the cephalosporin and quinolone antibiotic classes,22 and continued inappropriate treatment of ASB will worsen this problem. ASB recurs with organisms demonstrating increased resistance after antibiotic treatment.4,5,9,10 Adding an antibiotic to the regimen of this group of residents’ medications will only increase the likelihood of drug-drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, and the development of resistant organisms without providing benefit. If ASB continues to be treated needlessly, these problems will multiply. These facts lead the IDSA, the CDC, and the American Medical Directors Association to recommend that ASB not be treated in nursing home residents.1,11,14

CONCLUSION

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is prevalent in the elderly, and even moreso in those in the nursing home. Treatment of ASB not only contributes to antimicrobial resistance, but also increases morbidity from unnecessary prescriptions that can cause adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions. Clinicians certainly have good intentions when they find an abnormal urine and initiate therapy, but treatment of ASB in long-term care residents will result in more potential harm than good. It is not necessary to screen for or treat ASB unless a surgical procedure of the urinary tract is planned. If the nursing home resident appears ill but there are no symptoms clearly arising from the urinary tract, other sources should be sought for the change in clinical status. In this population, the probability of having ASB is higher than the probability of having UTI if specific localizing urinary tract symptoms are absent but urine testing is abnormal.

As the number of persons residing in nursing homes increases, so too will the use of antibiotics and resistance to them. Correctly distinguishing ASB from UTI and avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use can help mitigate this growing problem.

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.