Should We Offer Testosterone Replacement Therapy to Men Who Live in Nursing Homes?

PREVALENCE AND DIAGNOSIS OF HYPOGONADISM IN OLDER MEN

Hypogonadism can be defined as a serum total testosterone concentration of less than 325 ng/dL (11.3 nmol/L), with symptoms such as loss of libido, muscle mass, and strength.1 However, since the majority of older men report these symptoms, diagnosis on the basis of symptoms is difficult, causing many clinicians to rely on the serum testosterone concentration.

Measurement of the serum total (free plus protein-bound) testosterone concentration is a fair reflection of biologically active testosterone. However, bioavailable testosterone (free plus albumin-bound testosterone) more accurately reflects androgen status. Free testosterone, as measured by the analog method, which is the assay most commonly used in hospitals and commercial laboratories, typically gives a lower and less accurate estimate of androgen status than other methods.1

Ideally, blood samples should be obtained between 6:00 am and 10:00 am (to account for the circadian variation), and diagnosis of low serum testosterone should be based on at least two blood samples to account for the ultradian variation (frequent pulsatile release of testosterone into the circulation). In older men, these circadian and ultradian variations are blunted. However, obtaining two morning blood samples is still recommended.

Data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging demonstrate that 20% of men older than 60 years and 50% of men older than 80 years are hypogonadal.2 The average rate of decline in the serum testosterone concentration is 3.8 nmol/L (110 ng/dL) per decade.3 Because circulating testosterone is highly bound to sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), and because serum SHBG increases with age, bioavailable testosterone (free plus albumin-bound testosterone) declines more markedly with age than total testosterone.4

Testosterone declines even more substantially in ill older men, such as those who live in nursing homes. Thus, at least 50% of older men residing in nursing homes are likely to be hypogonadal. Low serum testosterone is associated with a depressed sense of well-being, loss of muscle mass and strength, decreased bone mineral density (BMD), and increased risk of fracture following a fall.5 These factors are important to clinicians treating nursing home residents, and especially when trying to rehabilitate the older man recovering from an adverse event such as hip fracture.

EFFECTS OF TESTOSTERONE IN OLDER MEN

Musculoskeletal

Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) have reported modest increases in lean body mass in men receiving testosterone replacement therapy (TRT).6,7 Some trials have reported increased grip strength,8 and several studies have addressed the question of whether TRT increases lower body strength.8-12 However, only two RCTs demonstrated substantial positive effects of testosterone on lower body strength.10,12 Table I summarizes the clinical trials of TRT in older hypogonadal men. Most of these studies reported that TRT improves body composition, with increased lean mass and/or decreased fat mass.8,13,14 However, the changes in body composition have been small and, in most cases, not accompanied by an increase in strength. Several studies have concluded that replacement doses of testosterone fail to increase strength in older hypogonadal men.8,9,11,14

Wittert et al11 administered an oral twice-daily dose of testosterone undecanoate 80 mg to men aged 60 years and older whose circulating testosterone was in the low-normal range. Twelve months of treatment produced a small increase in lean mass, a moderate decrease in adiposity, and no change in grip, quadriceps, or calf strength. However, doses were not titrated, the increase in serum testosterone was transient, and men with only low-normal testosterone may not benefit as much as men with low serum testosterone concentrations. Four reports have found that testosterone replacement increases strength.8,10,12,15 Sih et al8 found an 11-pound increase, and Bakshi et al15 reported a 13-pound increase in grip strength. Urban et al10 administered testosterone to a group of six older men and found a 25% increase in leg strength after 4 weeks of treatment.10 Ferrando et al12 gave replacement doses of testosterone to 12 elderly hypogonadal men, adjusting the dose to maintain circulating testosterone within the normal range. Lean mass and bicep, tricep, and leg extension strength all increased.

One reason for inconsistent strength improvement in older men may be that testosterone has been administered at low doses, particularly in the studies by Kenny et al6 and Brill et al.9 A recent study by Bhasin et al13 compared different doses of testosterone over 20 weeks in men aged 60-75 years. At supraphysiologic doses of 125 mg, 300 mg, and 600 mg per week (usual replacement dose is 75-100 mg/week), leg muscle strength increased. However, polycythemia, leg edema, and increased prostate size were also noted. The best tradeoff between beneficial and adverse events was seen with the 125-mg-per-week dose.

Low serum testosterone concentration is also associated with increased falls, impaired balance, decreased BMD, increased bone resorption, and minimal trauma hip fracture (fracture when falling from the sitting position).16 Testosterone replacement therapy leads to modest improvement in BMD.7 This effect is seen after 12 months of treatment and persists for at least 36 months. The increase in BMD is more prominent in men with lower baseline testosterone levels. No studies have looked at a decrease in fracture risk with TRT.

Importantly, increased prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and prostate size are a concern with long-term use. However, Amory et al17 compared testosterone plus finasteride versus testosterone alone. They found that the testosterone-plus-finasteride group had an improvement in BMD that was comparable to the testosterone alone group, but had much smaller increases in PSA and prostate size.

Rehabilitation Outcomes

Low testosterone is associated with decreased ambulation and increased mortality on a Geriatrics Evaluation and Management (GEM) inpatient unit.18 Testosterone replacement therapy may improve physical function (Functional Independence Measure [FIM] scores) and strength in these patients.15 In older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and low serum testosterone concentration, TRT increases lower body strength by 17%. The increase was even more pronounced when TRT was combined with resistance training exercises.19 High doses of testosterone before knee replacement may increase FIM scores.17 In the latter study, there was a small but statistically significant improvement in ability to stand on postoperative day 3. This improvement was not sustained on day 35, although this may be related to the brief period of testosterone administration. Although adverse effects were not observed, it is likely that they would be with a longer treatment.

Depression/Cognition

Low serum testosterone concentration in older men is associated with increased incidence and earlier onset of depression.20 However, most trials of TRT have not shown improvement in depression. Two small studies in younger hypogonadal men did show short-term improvement in depression with testosterone supplementation, but this effect has not been reproduced in older men.21 The age of onset of depression may also be a factor in response to testosterone. Perry et al22 reported that 6 weeks of testosterone treatment improved depression scores in men who had an onset of depression after the age of 45 years, but not in men whose depression started at a younger age.

Higher bioavailable testosterone levels are associated with better performance in cognitive tests.23 Short-term trials in healthy eugonadal older men have shown improvement in verbal and spatial memory.24 However, long-term trials (with 1 year of follow-up) did not show improvement in cognition or memory.25 Low testosterone levels are also associated with non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, such as apathy.26 A trial of testosterone replacement demonstrated trends toward improvement in non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease, but these were not statistically significant.27

Cardiovascular

Testosterone replacement therapy in hypogonadal men decreases total lipids and low-density lipoproteins; however, there was also an offsetting fall in high-density lipoproteins seen in some, but not all, studies.28 Triglycerides do not change significantly with testosterone administration. Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1, also decrease.29

Testosterone supplementation in hypogonadal men improves exercise tolerance and decreases exercise-associated ischemia in elderly men with coronary artery disease and low30 or low-normal31 testosterone. This may be secondary to a vasodilatory effect and/or higher pain threshold. The vasodilatory effect has been confirmed in animal models.32 The beneficial effects are seen with both acute33 and chronic30,31 testosterone administration, and also with low-dose30 and high-dose33 supplementation. However, none of these studies was long enough to show an effect on cardiovascular mortality.

Insulin Resistance

Several studies have demonstrated that insulin responsiveness improves in middle-aged and older men who are taking TRT.34-36 Marin et al34 treated abdominally obese middle-aged men with testosterone undecanoate 80 mg twice daily for 8 months. Although subjects were not demonstrably insulin-resistant at the beginning of the study, TRT resulted in an increased whole-body insulin responsiveness, as evidenced by a 20% increase in the glucose disposal rate (GDR) measured during hyperinsulinemic/euglycemic clamp studies. A strong relationship was exhibited between circulating testosterone and insulin sensitivity, with subjects who had the lowest initial serum testosterone concentrations displaying the greatest improvements in GDR. Testosterone replacement therapy caused a reduction in visceral fat, and that reduction may be the mechanism for improved insulin responsiveness. Treatment of older men with oxandrolone35 and treatment of middle-aged hypogonadal men with testosterone36 improved insulin sensitivity, as measured by fasting glucose and insulin concentrations (Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index [QUICKI] and Homeostasis Model Assessment [HOMA]). While the latter indexes do not correlate particularly well with GDR measured during clamp studies,37 they appear to be sufficiently accurate to confirm that TRT improves insulin responsiveness.

SAFETY OF TRT IN OLDER MEN

Risks of testosterone replacement in older men include fluid retention, gynecomastia, worsening of sleep apnea, polycythemia, and acceleration of benign or malignant prostatic disease.4 Among these risks, the potential effects of testosterone on prostate cancer are of the greatest concern. Initial fears that testosterone replacement would promote prostate cancer have been lessened by the findings of Hajjar et al.38 This retrospective, case-controlled study examined 45 hypogonadal men (mean age, 70 years) receiving TRT over a 2-year period. Compared to controls, treated individuals had a higher incidence of polycythemia, but no increase in prostate cancer. However, concerns for the testosterone treatment on the prostate have been rekindled by the recent release of 40-year data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging,39 which showed a positive correlation between prostate cancer and the blood concentration of free testosterone. In order to fully answer concerns about prostate cancer, prospective trials involving large numbers of subjects and long periods of treatment will be required. It is estimated that 10% of men will develop clinically manifest prostate cancer in their lifetime, and that 3% will die of the disease.40 However, autopsy data show a 42% prevalence of early-stage prostate cancer in men over 60 years of age.40 Prostate cancer has a slow progression and concerns remain that subclinical prostate cancer could be accelerated by TRT.

ROUTE OF REPLACEMENT

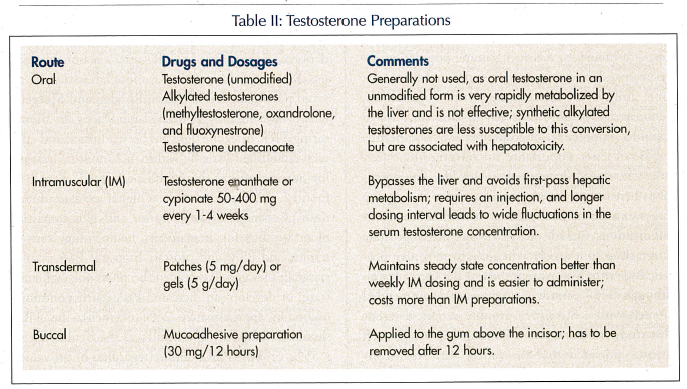

Oral testosterone in an unmodified form is rapidly metabolized by the liver and is not effective. Synthetic 17-alpha alkylated testosterone analogs are less susceptible to first-pass elimination, but are associated with cholestatic jaundice, peliosis hepaticus, and hepatomas, as well as adverse lipid profiles. Testosterone undecanoate, an esterified form, is available for oral administration. While testosterone undecanoate does not cause hepatotoxicity, concerns exist about its low and variable bioavailability.41 Table II presents an overview of available testosterone formulations.

Traditionally, the route of replacement has been intramuscular (IM), using testosterone esters, which are lipophilic. When given intramuscularly, testosterone avoids first-pass hepatic metabolism. Testosterone enanthate, undecanoate, or cypionate 75-400 mg IM every 1-4 weeks can be used. Disadvantages of IM testosterone include the required injection and the fact that a longer dosing interval leads to wide fluctuations in the serum testosterone concentration, which are high soon after injection and low shortly before the next dose. Polycythemia, acne, and gynecomastia are less common with transdermal administration of testosterone than with IM injection, probably because of the avoidance of high initial concentrations.42

Daily transdermal administration maintains a steady state concentration better than the weekly (or longer) IM dosing and is easier to administer. However, neither form of administration mimics the circadian and ultradian patterns of natural testosterone secretion. Transdermal products are available in patches (5 mg/day on the back, abdomen, upper arms, or thighs) or gels (5 g/day on the shoulders, upper arm, or abdomen). The transdermal preparations are effective in reversing hypogonadism and improving function. However, they are more expensive than the IM preparations.

Testosterone is also available as a mucoadhesive preparation for buccal application (30 mg every 12 hours). This is applied to the gum above the incisor and has to be removed after 12 hours. This mode of delivery has not achieved widespread acceptance compared to transdermal gels.

TARGET POPULATION

The decision to start a nursing home resident on TRT should be based on hypogonadal symptoms, a total serum testosterone concentration of < 300 ng/dL, the potential of the person to benefit from therapy, and the absence of contraindications. In 2002, the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists published guidelines for the treatment of hypogonadism in adult men.43 These guidelines identify hypogonadal symptoms that are critical in the decision to initiate TRT. The symptoms that are most important for a nursing home population are progressive decrease in muscle mass, loss of energy, poor ability to concentrate, and occasionally, menopausal-type hot flushes. Symptoms such as loss of libido, impotence, oligospermia, or azoospermia may be of lesser importance for nursing home residents who do not have an active sex life. The potential to benefit may be greater in patients undergoing post-traumatic or post-surgical rehabilitation. Contraindications include active or suspected prostate cancer, sleep apnea, polycythemia, severe benign prostatic hypertrophy, or carcinoma of the breast (rare). Although TRT cannot currently be recommended for men with a history of prostate cancer, a recent pilot study indicates that TRT may be safe in such patients, provided that the cancer was organ-confined and that PSA is low.44

MONITORING FOR EFFECTIVENESS AND SAFETY

In the early phase of therapy, serum testosterone should be measured and the dose adjusted to achieve a eugonadal level. For example, the initial dose of a transdermal gel should be 5 g per day of either of the 1% gels. After the individual has received the dose for approximately 14 days, a morning serum testosterone concentration should be obtained. If the morning serum testosterone concentration is still low (eg, < 300 ng/dL), the dose of testosterone should be increased to 7.5 g per day. The morning serum testosterone concentration should be rechecked 14 days after the dose adjustment. The dose can be further increased to 10 g per day, but in rare occasions, some persons still don’t become eugonadal, even at this high dose. This phenomenon is not fully understood but is likely related to poor absorption of the drug.

Once a resident has been on a stable dose of testosterone for at least 30 days, he should be evaluated for beneficial effects of testosterone. For example, has the person’s physical or cognitive function improved? Has the person’s motivation improved? Ideally, we should use objective instruments to make these assessments (eg, FIM) before and after starting TRT. If the resident has not responded to TRT after a reasonable trial (eg, 90 days), the treatment should be stopped to avoid potential adverse effects. Rhoden and Morgentaler45 have recently published guidelines for monitoring TRT. After the dose has been adjusted and efficacy established (usually within 1-2 months), testing for adverse effects should be performed every 3-6 months, and should include: a digital rectal examination; assessment of sleep apnea and gynecomastia; blood testing for hematocrit, hemoglobin, testosterone, and PSA; and prostate biopsy if PSA is substantially elevated. If a resident becomes polycythemic (rare) or develops an increased PSA (fairly common, occurs in approximately 25% of men), the TRT should be stopped. Specifically, if the hematocrit is > 55%, or if the PSA doubles (regardless of the value) or is > 4 ng/dL, TRT should be stopped.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Most male residents of nursing homes are hypogonadal. If a hypogonadal man displays hypogonadal symptoms and does not have contraindications to testosterone supplementation, he should be considered for TRT. This is especially true in men who are trying to recover from such injuries as hip fracture. Testosterone replacement therapy can be given as weekly IM injections, daily patches, daily gels, or twice-daily buccal patches. Each mode of administration has its strengths and weaknesses, but the daily gels may be the best option at this time. However, cost is an important issue, as with many medications. If the person is placed on TRT, the dose may need to be titrated, and outcome assessment is essential. In addition, vigilance for detecting developing adverse events (eg, polycythemia, rising PSA) is essential. Thus, residents should be monitored every 3-6 months.

Dr. Mulligan is an investigator for Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and Ascend Therapeutics, Inc. The research reported in this article was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Solvay Pharmaceuticals.