A Stepwise Approach to a Comprehensive Post-Fall Assessment

Falling, which was first described in the geriatric literature by Isaacs1 as “inadvertent landing to the lowest level,” was defined as a sudden and involuntary happenstance (hence, inadvertent), as in the case of an accident, and “not the result of loss of consciousness.” Since 1987, knowledge of fall etiology has expanded beyond the assumption that falls are mainly the result of accidents. Falls are a multidimensional phenomenon, attributable to medications,2-6 chronic7,8 and acute disease, age-related reasons,9-12 environmental causes,13,14 prodromal causes,15,16 or other etiology17 or idiopathic phenomena.

Although national guidelines for fall prevention exist,18 they are incomplete with regard to a comprehensive post-fall assessment. These guidelines leave much to the discretion of each clinician. A practical, organizational approach is needed that includes specific fall-related questions concerning symptoms, historical accounts, and situational contexts, and a pertinent physical examination in order to distinguish among various fall etiologies. This approach is especially important given the likelihood of symptom underreporting or dismissal of falls altogether by older adults.

As a widespread public health problem, falling has no geographic boundaries or age criteria, but its greatest impact is among the elderly. In 2001, more than 1.6 million seniors were treated in emergency departments for fall-related injuries, nearly 388,000 were hospitalized, and more than 11,000 elderly individuals died from fall-related injuries.19 Of the 50,000 U.S deaths from traumatic brain injury, falls are the leading cause among those age 75 and older.20 Because falls are such a pervasive, multifactorial, geriatric syndrome, the types of questions posed to older adults must also reflect a multifactorial set of content by care providers serving the elderly.

This article will outline a stepwise, organizational approach to the fall evaluation of an older adult that identifies symptoms and contexts associated with falls so that interventions can be tailored to likely etiologies. This approach takes into account the many interactive contexts that surround the older adult’s experiences, interpretations, and perceptions of a fall. As a vehicle toward greater understanding of the person’s experience and perception of a fall, it fosters opportunities for education, clarification of misconceptions about falling, and assistance in tailoring individualized plans of care.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

The stepwise approach for post-fall assessment is derived from two models: the Medical Model and the Illness Representation Model.21 Both models are clinically valuable in the formulation of any comprehensive fall evaluation and plan of care among individuals who are capable of discussing their thoughts. The combination of these models assists in identifying the causes of falls, directing medical plans of care, and identifying the individual’s perspective of the problem, which forms the basis of patient education initiatives, such as teaching the patient about causes of falling or clarifying ageist stereotypes associated with falling.

The Medical and Illness Representation Models

The Medical Model of care forms the foundation for existing clinical guidelines for fall prevention in the elderly.18,22 Many of these national recommendations, however, do not specify how the medical encounter is framed, or what questions are posed to older adults that can identify beliefs, attitudes, or perceptions of their falls.22,23 The American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society, and American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Panel guidelines recommend that clinicians “ask about falls routinely,” as part of routine care or as part of the fall evaluation, which should “include a history of fall circumstances, medications, acute and chronic problems, etc….”18 This line of inquiry is limited and may only result in “yes” or “no” close-ended responses or skeletal, circumstantial information about a fall. Entering into any medical encounter requires the practitioner to become aware of his or her patients’ beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions, as acquired from their experiences.

Falling is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon among older adults. One’s perception of falling is influenced by multiple factors and experiences, and therefore influences what one deems important to report. Each older adult who falls possesses varied perceptions of the event based on what he/she holds as truths that have developed from his or her own interpretation of the experience, past and current. In addition, individuals are influenced within a sociological context by myths and stereotypes about falling. Past and current experiences of falling contain specific attributes that form a representation of what it means to fall.

Supporting the inclusion of perspectives and attitudes about falls are some research investigations suggesting that older adults’ operative belief systems and perceptions are very important considerations in the health care encounter surrounding the fall.24-28 While factors such as fear of falling,24 the older adult’s perspective,25,26 knowledge,27 and perception of degree of risk28 influence that person’s choice of action, these same factors can influence his or her decision to disclose information about the fall to his or her care provider. The client’s perspective and attitude were among the eight health domains validated by a consensus group of expert practitioners to include in the standardized assessment of elderly people in primary care.29

A STEPWISE APPROACH TO FALL EVALUATION

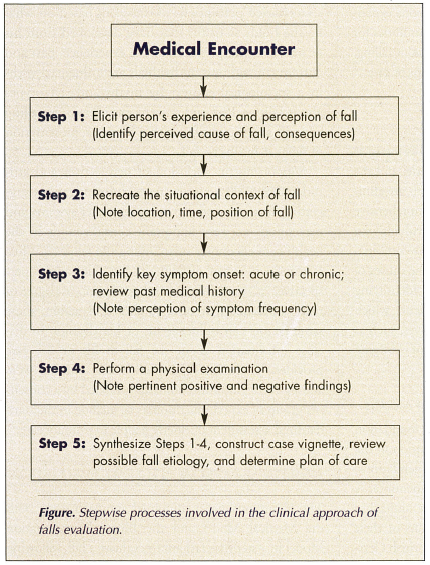

The Figure outlines a combined approach using both the Medical Model and the Illness Representation Model in a stepwise fashion to evaluate a fall, following the national recommendations and clinical causes of falls derived from the geriatric literature. This approach begins with: (1) eliciting the person’s experience and perception of his or her fall; (2) recreating the situational context of the fall; (3) identifying key acute and chronic symptoms and reviewing past medical history; (4) performing a physical examination; and (5) synthesizing relevant information, constructing a case vignette, reviewing fall etiology, and determining a plan of care. Each of the five steps in this approach is described below.

Step 1: How Do You Elicit the Older Adult’s Experience and Perception of a Fall in the History?

Discovering the person’s experience is usually learned when the practitioner makes open-ended statements, such as, “Tell me about your most recent fall to the ground; for instance, everything you can recall, how you were feeling.” A detailed description of the most recent fall will usually include a short story. Individuals might describe experiences ranging from “It was nothing, I just tripped, I was going along and then all of a sudden…” to “I’ll never forget how it made me feel: angry, frustrated, and feeling like it was one downward step.”26 Other remarks might include, “My knees buckled again, and down I went.” Listening to the older adult’s reflection and response is an important part of the history that can help to identify underlying etiologies as symptoms are disclosed. In addition, responses often reveal the person’s perception of fall causes, consequences, and other beliefs.

Step 2: Recreating the Situational Context of the Fall and Other Important Historical Information

Recreating a visual image of a fall helps the older adult to recall specific circumstantial information about the fall, as well as to point to a possible underlying etiology. This is elicited by asking the older adult to recall where he or she was and what he/she recalls as an activity. As recommended in the national practice guidelines,18 the practitioner reviews the exact circumstances of the fall, such as time of occurrence, location, or activity when the fall occurred. During the discussion about activity, it is helpful for the care providers to ask questions about and then recreate their own visual image of the events leading to the fall, whereby possible etiologies can be identified. The sharing and comparison of visual images constructed by both the practitioner and the individual can clarify important events associated with the fall.

Considering the fall and/or associated symptoms relative to the person’s body in space at the time of the fall may be helpful in deciphering the underlying etiology. For instance, was the person lying down, or attempting to get up or to sit down? If the person was getting out of bed, did he/she need assistance? Responses may point to neuromuscular or cardiovascular problems, or to a situation related to environmental concerns. A new onset of lightheadedness with a position change (eg, sitting up or standing) may be indicative of orthostatic hypotension, whereas lightheadedness with exertion upon walking may be indicative of cardiovascular involvement or a medication side effect.

Step 3: What Are the Key Acute or Chronic Symptoms Associated with Falling?

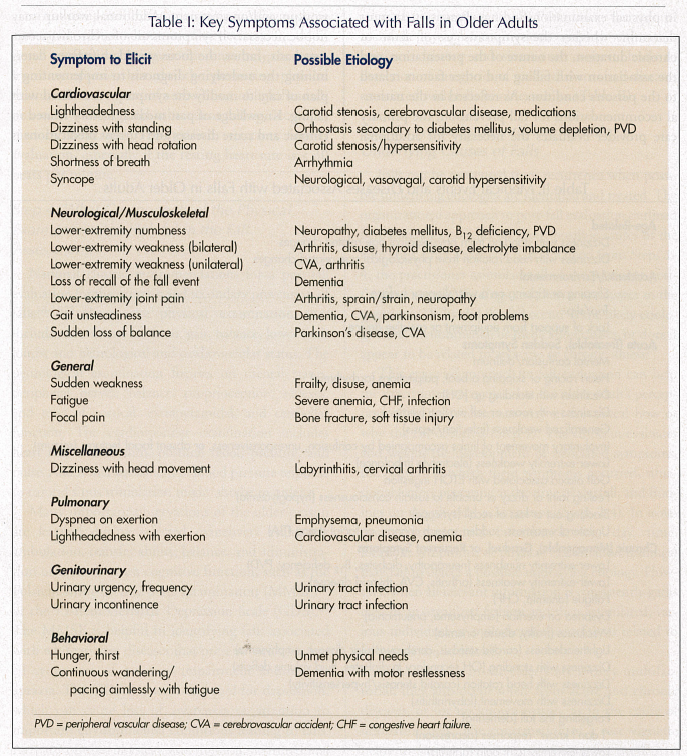

Embedded in the rich descriptions and personal accounts of falling described in Steps 1 and 2 are discernable symptoms often linked to possible underlying causes of a fall. A comprehensive review of common symptoms associated with falling, arising from either acute or chronic etiologies, can be elicited and determined (Table I). It is important to note symptom onset, duration, and frequency. Because older adults may not voluntarily report these symptoms or may fail to recognize their relationship to the reason for a fall, it is incumbent upon the practitioner to ask about their occurrence and association with falling. Review of past medical history and medication regimen may also reveal the new onset or continuation of key symptoms.

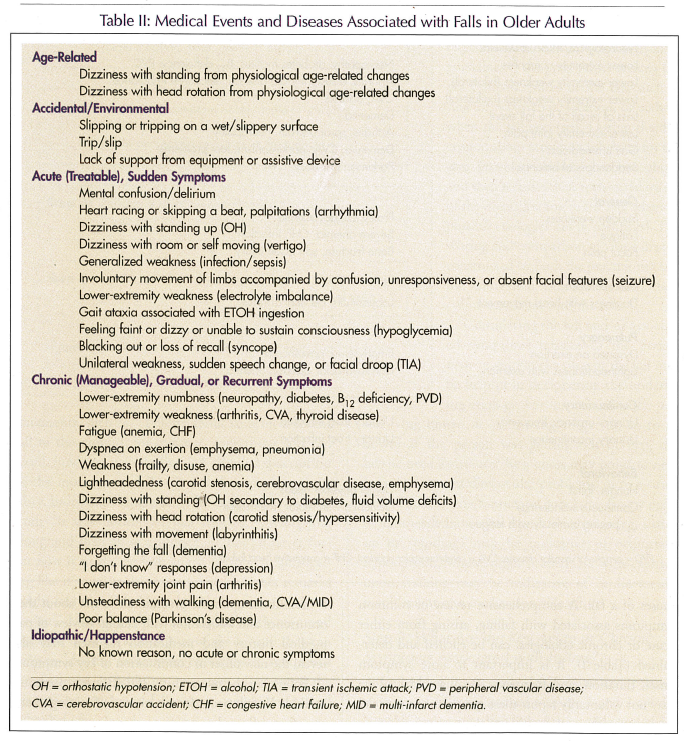

Following the overarching classification presented in Table II, falls occur from a myriad of etiologies and are often reflected as acute or chronic symptoms, or in physical examination findings. Practitioners must determine whether the symptoms are of acute or chronic duration, the nature of the presentation, and the association with falling and other factors related to the person’s condition. As reflected in the national recommendations for fall prevention, the primary care provider evaluates the necessity for additional workup and/or treatment. Additional workup may not be necessary if symptoms are of a chronic, recurrent basis; rather, the focus would shift from determining the underlying diagnosis to implementing a plan of care to modify the symptoms associated with falling. Knowledge of past medical history related to chronic and acute diseases and current medications is a critical component of any assessment of symptoms associated with a fall event. The decision for additional workup is contingent upon not only the severity of symptoms, but also the presenting physical examination. A report of a new onset of lightheadedness with standing and subsequent falling, accompanied by orthostatic hypotension, warrants further evaluation, especially if the resting heart rate is < 30 beats per minute.

Step 4: What Components of the Physical Examination Are Helpful in the Fall Assessment?

National clinical recommendations for a post-fall evaluation for the primary and secondary prevention of falls18,22,23 direct the physical examination that includes assessment of vision, gait, balance, lower limb joints, and neurological and cardiovascular status. The neurological examination focuses on mental status, peripheral nerves, balance, proprioception, reflexes, and tests of cortical, extrapyramidal, and cerebellar function. The cardiovascular examination includes heart rate and rhythm, postural blood pressure, and pulse. Additional assessment of blood pressure response to carotid sinus stimulation might also be in order.

Many important observations of the older person are learned during selected maneuvers evaluating ambulation, transfer ability, balance, and administration of tools to assess cognitive function, such as the Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)30 or the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS).31 The MMSE is helpful in identifying falls associated with white matter diseases that present with associated symptoms of memory impairment and/or gait apraxia. The GDS is a screening tool for depression, which can cause loss of awareness or attention to important environmental conditions leading to falls. As part of the physical examination, a functional assessment is performed with emphasis on transfer ability, ambulation, turning ability, and ability to sit and stand. Performance is rated as independent or requiring assistance or supervision. The use of any mobility aids is noted in relation to enhancing function. As specified in the national recommendations, the fall assessment also includes administration of selected measurement tools. Performing the recommended physical examination, coupled with other pertinent history and situational context, leads to detection of categories of medical events and diseases associated with falls in older adults (Table II).

Step 5: Synthesis: Identifying Possible Underlying Causes of Falls

Falls can be prevented from recurrence when possible underlying etiologies are identified and treated. The organizational approach to post-fall evaluation outlined here leads to a conclusion about possible causes of the fall. Thus, after reviewing data obtained from Steps 1-4, the practitioner assimilates all of the pertinent positive and negative findings and derives an answer to the questions, “Why did the fall occur? Is the likely etiology from environmental or medication causes, or does it appear to be related to an acute or chronic illness?”

This stepwise approach to fall evaluation can help the practitioner recognize that the older adult’s perception of the fall occurrence may in fact reveal how or why the fall occurred (Step 1). The clinician evaluates and weighs the development of associated symptoms, the context in which these symptoms occurred, situational factors operating at the time of the fall, and findings on the physical examination (Steps 2-4). In isolation, circumstantial information (eg, day, time, location, symptoms, or physical examination findings) may fail to detect a possible underlying etiology. However, when all relevant information is consistently gathered in an organized fashion and then assimilated, various individual or multifactorial conditions related to falling can be addressed.

Although falls in the elderly are mostly multifactorial, they also occur solely from acute and chronic diseases, or for no known reason, as in the cause of idiopathic falls. The construction of a case vignette helps to synthesize relevant information needed to determine possible underlying etiology for consideration. Following are three case vignettes, which serve as examples of falling from idiopathic reasons, acute medical events, and chronic diseases. The cases are reported from primary care practice with older adults who sought a fall evaluation from a geriatric fall assessment and prevention program.

Consider the following case example of a healthy and well-functioning older adult (with no prior falls or risk for falling) who fell while grocery shopping.

-----

Case Example: Idiopathic Fall

A 90-year-old female reported slipping while grocery shopping. When asked to further describe her most recent experience with the fall, everything she could recall, and her thoughts, she commented, “Who would believe this one! I was shopping, pushing my cart along, and then suddenly I was on the ground. I looked down, and I had slipped on a banana peel. There was a mom with her children I could see in the distance; I guess that was the cause, and it startled me, but fortunately I did not break anything.”

-----

This slip was actually a true fall resulting in a landing to the lowest level, an accident that occurred for no known predictable reason or organic etiology. Not all falls with this description are due to environmental accidents. The only means of determining underlying etiology is through a thorough history, physical examination, and other tests and procedures to rule in or rule out other causes. In this case, a complete review of systems and physical examination revealed a healthy 90-year-old female with no underlying medical conditions, taking no medications, and presenting with no symptoms associated with an acute type of treatable fall. A fall such as this one appears to be happenstance, irrespective of any predetermined risk status, functional status, or age. This type of fall could be classified as idiopathic since there are no presenting or uncovered symptoms or physical examination findings that might lead the clinician to suspect otherwise. It is important to note that embedded in her description of the falling event was her perception of causation.

When falls are not attributed to idiopathic reasons, they occur from specific identifiable reasons. Table I illustrates a global categorization of falls attributable to etiologies, heralded by a presenting symptom or a significant physical examination finding. This categorization of falls could be classified as secondary to acute treatable events, symptoms of chronic conditions, side effects of medications, or simply to age-related physiological changes. Some falls share multiple etiologies, as in the case of orthostatic hypotension arising from volume depletion or bleeding (acute), autonomic neuropathy (chronic), or a side effect of medication (medication-related). The following case illustrates an acute treatable fall.

-----

Case Example: Acute Treatable Fall

An 82-year-old woman who lived alone was brought into the office for an emergency evaluation after her nephew observed her fall to the ground while she raked leaves outdoors. When the patient was asked to describe her fall experience, little information was acquired. She commented, “I don’t know what happened.” A comprehensive review of key associated symptoms later revealed that she had feelings of lightheadedness and dizziness while raking. These symptoms, acknowledged to be of a new onset, were consistent with a transitory syncopal event. There had been no prior falls. In the ambulatory geriatric clinic, she underwent a complete review of medications and history, and a comprehensive physical examination. Her physical examination showed a drop in systolic blood pressure of 30 mmHg from supine to standing position with dizziness. There was no dizziness with head movement. Cardiovascular examination revealed a systolic murmur grade 2/6 at the apex. An electrocardiogram revealed a Mobitz type II heart block and normal sinus rhythm with a rate of 40. The woman was transferred to the emergency room, where she received an emergency pacemaker. Three-month follow-up revealed no recurrent falls and a return to usual daily activities.

-----

The initial description of a sudden fall, for which the patient could not explain any possible causation, was puzzling, especially since it was of new onset and occurred in a healthy older adult. Significant information that was learned in Step 1 was the patient’s inability to clearly describe her recent fall experience (suggesting a possible loss of recall). Even though a lack of recall existed, proceeding with Steps 2-4 allowed for a more precise description to be discovered, which later led to a tentative diagnosis of a syncopal fall, confirmed on the physical examination and diagnostic evaluation. Other types of situational contexts in which falls occur include those falls that occur from symptoms associated with underlying chronic illness. Consider the following case example.

-----

Case Example: Fall Associated with Chronic Disease

A 72-year-old female reported having had multiple falls, at least three times weekly, of a longstanding duration when walking to the store. When asked why she frequented the store so often, she revealed a complaint of tiredness and leg heaviness that precluded her from carrying heavy groceries once per week. She perceived this to be the cause of her fall. Further history and physical examination revealed a focal lower-extremity weakness of the left leg. There was no past history of arthritis, neurological or cardiovascular disease, or diabetes. Neurological evaluation and electromyography revealed a pattern consistent with post-polio syndrome. Management was directed at changing the pattern of grocery shopping and taking frequent rest periods. This combination reduced fall episodes and helped the patient to feel less fatigued in her legs.

-----

A very important aspect of this person’s fall might have been missed if a visual re-creation of the situational context was not included in the assessment (Step 2). The practitioner was able to re-create and visualize a fall occurring as the patient lifted her leg to step up onto the curb, revealing that the falls did not occur during walking. This small but important detail added clarity to the situation and helped to explain the frequent falling in light of the symptoms elicited on history and the physical examination findings.

DISCUSSION

Evidence-based recommendations for evaluation of falling among older adults19,23,24 exist to guide clinicians in practice to discern the various reasons for the fall and to determine appropriate solutions to prevent their reoccurrence. Their implementation is carried out through a classic Medical Model approach to history taking and physical examination, which relies in part on individuals reporting important clinical information in a succinct fashion. To date, no efficient, comprehensive practice approach has been proposed in the literature, which incorporates the person’s perception of the problem with the consensus guidelines for the recommended elements. Given the many plausible clinical explanations for falls,2-18 older adults may have their own individualized perceptions of the causes and consequences of falls.25-27 It seems appropriate that including their view about a fall should be advantageous to the clinician and an integral component of any fall assessment or management strategy.

This article outlined a comprehensive, organized, stepwise approach to assist clinicians in practice when conducting a post-fall evaluation reflective of current clinical guidelines and standards of care. A distinguishing feature of this new approach—unlike the classic history, physical examination, and functional assessment—is that it attempts to create a synthesis of important information into a meaningful whole, so that symptoms associated with falling are identified and can be managed accordingly. Including the individual’s perception of the fall event and his or her symptoms is an important aspect of the overall care of any person. Tinetti and Fried32 argue that disease as the focus of medical care provides the framework for diagnosis and treatment, but often negates an integrative and individualized approach to care. Certainly, when considering falls, we need to move beyond a disease focus and integrate the perception of that fall from the perspective of the individual.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

In all patient and resident settings, the goal of post-fall assessment is to identify falls amenable to intervention, such as falls occurring from key acute or chronic illnesses, medications, environment, or other conditions. Using the stepwise approach described in this article, underlying fall etiologies can be determined and lead to targeted interventions. This approach can differentiate various types of treatable falls based on a composite synthesis of the person’s experience, situational context, medical history, and presenting symptoms. This information, coupled with the individual’s perception of his or her falls, can best direct future interventions aimed at education, demystification of falls, and the secondary prevention of falls.

Attention to discerning the type of fall that occurs assists greatly with acquiring a body of knowledge detailing various types of falls among older adults. Ultimately, when different types of falls are presented, case definitions can be better defined, and fall epidemiology can be more precisely determined. In the long run, fall incidences can be better tabulated, and resources for their management can be best planned by practitioners and public policy officials.

Fall prevention in elderly persons is a goal shared by all care providers that begins with accurate accounts not only of the frequency of falls, but the types of falls that occur. The stepwise approach provides a framework for important data that can be systematically collected and analyzed so that various fall incidences can be tabulated, trends can be analyzed, and fall prevention programs can be further individualized.

Dr. Johnson is the recipient of the NIH;K07 Award for Long-Term Care Research.