Prevention of Suicide in the Elderly

INTRODUCTION

In nearly all countries of the world, elderly people are more prone to suicide than the general population.1 Our knowledge of epidemiology and risk factors for suicide in older adults has been expanded in the last decade2 through surveillance efforts1,3 and sophisticated psychological autopsy studies.4-6 Clinical trials that evaluate intervention strategies are starting to emerge. Nevertheless, managing elderly persons at risk for suicide in clinical practice remains a daunting task. Moreover, while the personal and social consequences of suicide are devastating, clinicians may not see its prevention in the elderly as a priority.7

This review is intended for a broad clinical audience. The authors aim to provide a recent literature update with an emphasis on clinical guidelines and intervention strategies.

ELDERLY SUICIDE AS A PUBLIC HEALTH PROBLEM

Despite the difficulties in estimating the true incidence of suicide,8,9 it is clear that the age-adjusted suicide rate among U.S. elderly (age 65 and older) is higher than in any other age group—15.5 per 100,000 compared to 11.0 in the general population in 2002. This increased suicide rate largely reflects the growth in the number of suicide deaths with age among Caucasian males.3 Suicide attempts in older persons are much more lethal than in their younger counterparts.10 Depending on the definition and the assessment method, estimates of the prevalence of suicidal ideation in community-dwelling older adults range from 1-12%.11-15 Remarkably, the prevalence of hopelessness, thoughts about death, and suicidal thoughts,13 as well as the incidence of suicide attempts4 and completed suicide,4,5,16 are much higher in the elderly with depression than in older people without depression.

ASSESSMENT: ESTIMATING SUICIDE RISK

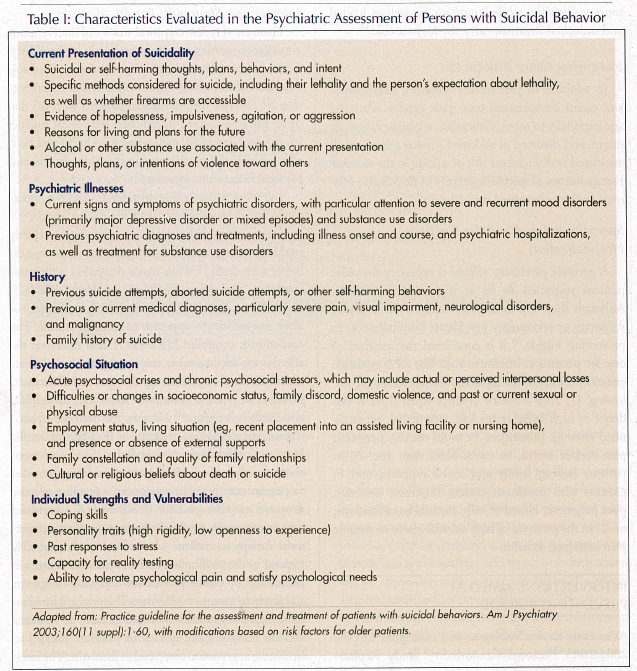

A careful clinical assessment enables estimating short- and long-term suicide risk and making decisions about the level of care and treatment accordingly. Nonetheless, a clinician needs to accept a degree of uncertainty, since it may not be possible to accurately predict whether or when a particular individual will commit suicide. The American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Practice Guideline for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors provides a detailed description of the assessment process in adults.17 Guidelines for managing high-risk elderly suicidal patients in primary care settings were published by the Prevention of Suicide in Primary Care Elderly: Collaborative Trial (PROSPECT) Study Group.18 Essential areas of the diagnostic interview are summarized in Table I. We will review these recommendations briefly below, stressing research findings and practices that pertain to older persons.

Assessment of Current Suicidal Ideation

This is a central part of suicide assessment, which is often missed in older individuals, even when depression is suspected.19 Open-ended questions dealing with a person’s feelings about living should be followed by specific questions about the nature, timing, and context of suicidal thoughts. The value of obtaining collateral history from family, friends, and other informants cannot be overemphasized, especially with patients who deny suicidal ideation. When suicidality is suspected, these informants can be contacted without the individual’s permission.17

An original approach to eliciting suicidal ideation based on psychiatric emergency room experience, known as CASE (Chronological Assessment of Suicide Events), was put forward by Shea.20-22 The method aims to increase the validity of elicited data, and to make the clinical assessment less biased by the individual’s subjective perceptions and defenses. One of the “validity techniques” used is behavioral incident,23 requesting specific facts, details, or trains of thought (eg, “Tell me what happened after you took the pills.”).

Another technique, gentle assumption,24 is a leading question that implies the presence of behavior or ideation to which the person may not otherwise admit (eg, “What other ways have you thought of killing yourself?”). In denial of the specific, the third validity technique, the interviewer asks a series of particular rather than general questions, which are more likely to elicit positive responses (eg, “Have you thought of shooting yourself?” instead of “Have you thought of suicide?”). The author emphasizes that these inquiries should not be combined into misleading “cannon questions” (eg, “Have you thought of shooting yourself, overdosing, or hanging yourself?”). The CASE approach involves gathering clinical data in the following sequence: (1) presenting suicidal ideation/behavior; (2) recent suicidal ideation/behaviors; (3) past suicidal ideation/behaviors; and (4) immediate suicidal ideation. The strategy has the advantage of high face validity, but lacks empirical support, and was not designed specifically or adapted for older persons.

To evaluate the severity of depression and the presence of suicidal ideation, the clinician can use structured, brief depression scales containing a suicide item, such as the self-administered Beck Depression Inventory25 or the rater-administered Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D).26 For a more focused assessment of current suicidal ideation in the elderly, we recommend using the first five items of Beck’s Scale for Suicide Ideation.27 It also assesses indirect self-destructive behaviors, such as not taking medications or not eating as a way of hastening death.

Focused Psychiatric Evaluation

One needs to identify psychiatric symptoms such as hopelessness,28 impulsivity, and agitation, all of which have been associated with suicide or suicide attempts in the elderly. It is mandatory to obtain the history of past suicide attempts, aborted suicide attempts, or other self-destructive behaviors, especially recent ones. Suicide attempts in older persons need to be considered especially carefully. In a multicenter European study by De Leo and colleagues,10 the attempt-to-completion ratio among elderly males was estimated to be as low as 1.2 to 1. Prior attempts are a common antecedent of completed suicide in the elderly, especially in females.6 Past psychiatric treatment history can provide valuable information about prior suicide attempts, suicidal ideation, hospitalizations, and coexisting disorders. It is crucial to obtain information from the individual’s previous physicians. The person’s presentation needs to be placed in the context of the psychosocial situation and stressors. Elderly males are particularly vulnerable to suicide immediately after an interpersonal loss, such as the death of a spouse.29

Formulating the Psychiatric and Medical Diagnosis

While 77-97% of elderly suicide decedents suffer from psychiatric illness, according to studies from New Zealand, U.S., Sweden, Hong Kong, and Canada,4-6,30-32 suicide risk is highest with severe and recurrent mood disorders, particularly unipolar and bipolar depression. According to a Finnish study, mood disorders in the elderly are commonly not diagnosed until a suicide attempt is made.33 Substance use disorders and, to a lesser extent, psychotic disorders, are other important conditions in the elderly.4,6,32 Comorbid medical conditions can be equally important, especially visual impairment, severe pain, neurological illness, and malignancy.32,34

Evaluating the Patient’s Access to Firearms

Another crucial step that is often missed is asking about firearms at home.35 In the elderly, the availability of guns was found to be an independent risk factor for completed suicide.36-38 Men appear to be more vulnerable, while handguns, as well as loaded and unlocked firearms, carry the highest risk.38

Identifying Other Risk Factors

In addition to past suicide attempts, hopelessness and recent interpersonal loss, male gender, advanced age (especially in men), Caucasian or Native American origin, and divorced or widowed marital status, are all associated with increased risk of suicide in the elderly.3 Family history of suicide, especially in first-degree relatives, indicates increased suicidal risk.

Specialty Referral and the Need for Hospitalization

A geriatric psychiatry referral is necessary for older patients suspected to be at high risk for suicide. Although there are no data to support the utility of voluntary or involuntary psychiatric hospitalization in preventing suicide,39 it is considered the standard of care for patients at imminent risk. The APA guideline generally recommends inpatient admission for the following: (1) after a suicide attempt when there is evidence of high lethality (violent, near-lethal, premeditated attempt, precautions to avoid rescue), persistent plan and/or intent, in males older than age 45, in patients lacking family and social supports, and in patients with psychosis, current impulsive behavior, poor judgment, refusal of help, medical complications; or (2) in the presence of high suicidal intent or specific plan with high lethality.

INTERVENTIONS AIMED AT PREVENTING SUICIDE

As recently shown by Kessler and colleagues40 in the 2001-2003 National Comorbidity Study Replication, albeit in a younger population sample, a significant improvement in access to treatment among people with suicidal thoughts, plans, gestures, or attempts since the early 1990s failed to translate into a reduction in suicidal ideation or behaviors. Therefore, in addition to promoting access to medical and mental health treatment, enhanced and targeted assessment and intervention strategies are needed to prevent suicide.

Intervention Strategies: Empirical Studies

There are very few empirical studies of interventions aimed at preventing suicide, particularly in the elderly. This can be explained in part by: (1) the rarity of suicide as an outcome; (2) the assumption that treatments that are effective for nonsuicidal patients with the disorder will also succeed in reducing the risk of suicide; (3) the problem of balancing potential harm and benefits for high-risk participants in the study design; and (4) legal risks to investigators.41

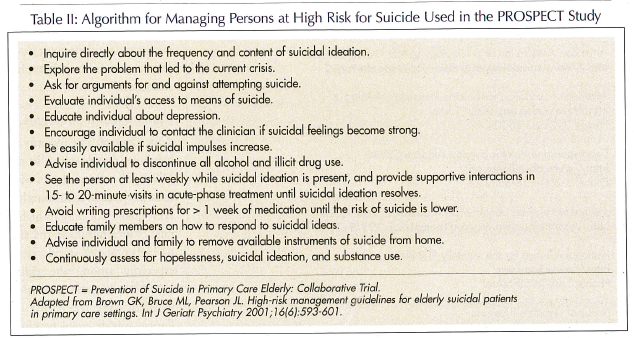

The primary care setting provides an excellent opportunity for intervention to reduce the risk of suicide,42,43 particularly given that a significant proportion of elderly suicide decedents see their family physician in the months before their death.44 While major depression is the most important underlying condition in elderly suicide,4-6 improving its detection and treatment is a necessary—albeit not sufficient—approach to reducing suicide. The randomized, controlled PROSPECT trial examined the effectiveness of depression care management and treatment guidelines in patients age 60 years and older in 20 primary care practices in the New York City, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh regions.45 Notably, the outcome assessed was suicidal ideation, as measured by the Scale for Suicide Ideation,46 which limits one’s ability to draw conclusions about the effect on suicidal behavior. Guidelines provided to primary care physicians suggested a first-line selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) trial. A master-level care manager with psychiatric backup provided interpersonal therapy to patients who refused or did not fully respond to the medication, and worked with patients in person and by phone to monitor depressive symptoms and promote treatment adherence. The protocol for managing high-risk patients is described in Table II.18 Suicidal ideation resolved more quickly in practices assigned to receive the intervention compared to usual care. The intervention was also successful in reducing depressive symptoms in patients with major or minor depression and suicidal ideation. Despite limitations and methodological difficulties, the findings of the PROSPECT study are encouraging: structured assessment of elderly patients with depression emphasizing suicidal ideation, coupled with guideline treatment managed by a master-level clinician, reduce both suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms, hopefully diminishing the risk of suicide in late life.

The utility of depression care management for older patients in primary care practices was shown in another large trial conducted in primary practice settings, the Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment (IMPACT) study.47 The 12-month intervention included: (1) behavioral activation/pleasant events scheduling; (2) weekly-to-monthly follow-up by a depression care manager; and (3) an SSRI or other newer antidepressant (approximately 85% of participants) and/or a modification of cognitive behavior therapy known as “Problem-Solving Treatment in Primary Care,” which includes 6-8 individual sessions followed by monthly group maintenance sessions (approximately 35% of participants). The baseline prevalence of suicidal ideation, as assessed by the suicidal ideation item from the 20-item depression subscale of the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (SCL-90),48 was 15% in the intervention group and 13% in the usual care group. It was significantly lower in the IMPACT group than in the usual care group at 6 months (8% vs 12%), 12 months (10% vs 16%), 18 months (8% vs 13%), and 24 months (10% vs 14%).49

Active ingredients of the IMPACT and PROSPECT trials can be described as a combination of: (1) screening for depression and suicidal ideation with simple, standardized instruments; (2) improving access to depression treatment by integrating it into primary care; (3) enhancing the quality of depression treatment with psychotherapy and medication algorithms; and (4) an algorithm for managing high-risk patients.

A Japanese community-based program, which combined a two-step depression assessment of all elderly in a rural town with psychoeducation for participants who screened positive for depression and psychiatric referral for those meeting clinical criteria, reported a reduction in long-term suicide rates. The design, however, was quasi-experimental, with neighboring communities serving as controls.50 Similar programs exist in several Japanese prefectures and municipalities, and typically include screening for depression with subsequent referral for psychiatric treatment and/or psychoeducation.51,52

An alternative approach targeting vulnerable community-dwelling elderly is exemplified by a semi-naturalistic Italian study by De Leo and colleagues.53,54 Investigators assessed the suicide rate among 18,600 individuals age 65 years or older (mostly widowed women living alone), who received access to a 24-hour emergency alarm service and twice-weekly phone checks through a portable communication device (Tele-Help/Tele-Check). Participants were identified by community social workers or general practitioners, based on their perceived need for help (disability, social isolation, psychiatric illness, nonadherence, etc). The difference between the observed suicide rate and the expected rate, based on general population statistics, was significant for females but not for males. While the demonstrated feasibility of this intervention is important, its true effectiveness is difficult to assess in the absence of operationalized inclusion criteria and an actual control group.

With respect to suicidality in older persons with depression, we have previously reported on an analysis of pooled data from three treatment trials.55 Among 395 individuals aged 59-95 years, 77.5% had suicidal ideation or recurrent thoughts of death, or the feeling that life was empty at the onset of treatment. With protocolized treatment, which included nortriptyline or paroxetine combined with interpersonal therapy, suicidal ideation resolved rapidly in all but 4.6% of individuals. Suicidality was associated with early-onset, recurrent episodes, longer time to remission, and lower remission rate, supporting the idea that suicidal ideation in treatment is associated with chronic, difficult-to-treat depression rather than a paradoxical increase in energy on antidepressant medications or the “rollback phenomenon.”

Public Health Strategies

Gun Control. The majority of elderly suicide decedents in the U.S. kill themselves with firearms.3 Access to firearms has been linked not only to higher rates of firearm suicide, but also to higher overall suicide rates, especially among the elderly,36,38,56 raising the question of whether some decedents of firearm suicide could be saved by more effective gun control policies. A critical review of available cross-sectional and interrupted-time-series studies by a National Research Council committee showed that while stricter gun control laws may reduce the rates of firearm suicide, the findings for overall suicide rates are mixed.37

Community Education. Education for the public, particularly the elderly and their caretakers, as well as health care providers, was a component of the Japanese intervention programs.50-52 However, it has not been empirically tested as a separate intervention.

SPECIFIC TREATMENTS

While few or no studies demonstrate their effectiveness in the elderly, several treatments have been consistently shown to reduce suicide rates in younger adults with mood disorders and schizophrenia.

Lithium in Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder

As shown in a recent meta-analysis,57 lithium maintenance treatment is associated with large reductions in the rate of completed suicide and suicide attempts in patients with bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, and recurrent major depression. Lithium treatment requires close monitoring, in part due to the overdose potential, especially in the first 3 years of treatment, and in patients with prior suicide attempts.58 In the elderly, there is some empirical support for lithium augmentation as an effective strategy for managing patients whose major depressive illness only partially responds to antidepressants,59-61 although the benefits need to be weighed against an approximately 40% rate of moderate and severe side effects.62

Clozapine in Schizophrenia

The protective effect of clozapine against suicide in patients with schizophrenia has been shown in a U.S. prospective study,63 as well as in U.S. and UK registry studies,64-66 but not in a subsequent study of the effect of clozapine on completed suicide in the Veterans Affairs system.67 More solid evidence was provided by a recent randomized comparison of clozapine to olanzapine, which found clozapine to be superior to olanzapine in reducing suicide attempts and hospitalizations to prevent suicide.68 This advantage, however, needs to be considered in the context of the serious metabolic effects of clozapine.69 Clozapine has been shown to be an effective treatment for older adults with psychosis.70-72 Slower titration and lower dosing seem to improve tolerability and help the patients stay on clozapine.71,72

Electroconvulsive Therapy in Major Depressive Disorder and Bipolar Disorder

Studies performed in younger adult and mixed-age samples provide sizeable evidence that electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) reduces suicidal ideation in the short term, especially in patients with severe depression.73,74 Its effectiveness and rapid onset of action make it particularly useful in patients whose life is threatened by acute suicidality or refusal to eat as a result of depression or psychosis.17,75 A recent multicenter study of bilateral ECT in a group of 444 patients age 18-85 years with major depressive disorder found a rapid reduction in suicidal ideation,76 as measured by the suicidality item of the HAM-D.26 This effect appeared stronger in patients over age 50 years, and the resolution of suicidal ideation was positively correlated with age, a finding that agrees with previous data showing similar or better response to ECT in older aduts with depression compared to their younger counterparts.77 Overall, the efficacy of ECT in the treatment of late-life depression is well established.78

Antidepressants

The ability of antidepressants alone to prevent suicide has not been demonstrated in controlled trials in any age group.79,80 However, indirect evidence from population-level studies suggests that SSRIs may be protective against suicide,81,82 particularly in older people.83 Combined with their safety in overdose, this may be an argument supporting the utility of SSRIs in the treatment of suicidal elderly.

CONCLUSION

The high prevalence of suicide in older people and its largely treatable etiology compel clinicians as well as policymakers to improve the existing prevention efforts. Our improved understanding of risk factors for suicide provides several avenues for intervention. The strategy of enhanced detection and collaborative treatment of depression in primary care currently has the most empirical support. Telephone support and emergency alarm service also have promise. Lithium and electroconvulsive therapy decrease long-term and short-term suicide risk, respectively, in severely ill persons with mood disorders. Clozapine has been shown in most studies to be effective in reducing suicide rates, hospitalizations to prevent suicide, and suicide attempts in schizophrenia.

While the intervention studies described above are promising, their findings are limited by not having suicidal behavior as an outcome,45,49 or by a lack of an adequate control group,50,54 so conclusions should be drawn with caution. Since medical conditions such as severe pain, neurologic disorders, vision loss, and malignancy interact with mood disorders resulting in higher suicide risk, conceivably, appropriate medical treatment may reduce the risk of suicide.

Suicide rates fluctuate, and long-term studies are required to evaluate the effect of prevention efforts. There is a great need for large rigorous trials focusing on high-risk groups, such as depressed elderly persons with suicidal ideation or past attempts, to assess the effectiveness of these interventions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Jürgen Unützer for providing information about the IMPACT trial.