Complications of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in the Elderly

INTRODUCTION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common upper gastrointestinal problem seen in clinical practice. It is estimated that 10-20% of adults have symptoms at least once weekly, and 15-40% have symptoms at least once monthly.1 Up to 20% of persons seeking medical care for GERD have complications.2 Although there is a tendency to reduced frequency of heartburn and acid regurgitation in older persons, several studies show that the frequency of GERD complications—such as esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal cancer—is significantly higher in the elderly. Collen et al3 found an increase of esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in persons over 60 years of age compared to those younger (81% vs 47%). Huang et al4 also found more severe gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal lesions in elderly individuals, as compared with younger ones.

PATHOGENESIS

A number of abnormalities that appear to play a pathogenic role in GERD are often more serious in elderly individuals and increase the rate of complications. These include a defective antireflux barrier, abnormal esophageal clearance, reduced salivary production, altered esophageal mucosal resistance, and delayed gastric emptying. Injury to the esophagus is due primarily to gastric acid and pepsin. In some cases, duodenogastric reflux of bile may cause the injury.5 In addition, nocturnal gastro-esophageal reflux is associated with more severe manifestations and esophageal and extraesophaeal complications of GERD, and may be more common in the elderly.6-8 The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is the antireflux barrier. Abnormalities that make it dysfunctional promote acid reflux and the constellation of GERD problems. The most common cause of reflux episodes is transient LES relaxations, the drop in LES pressure not accompanied by swallowing. Incompetence of the LES was shown by Huang et al4 to be more prevalent in the elderly. Multiple medications that are taken by elderly persons are well known to decrease LES pressure, such as those for hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and pulmonary disease. These include nitrates, calcium-channel blockers, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and antidepressants. The presence of a hiatal hernia impairs the function of the LES and may impair the clearance of refluxed acid from the distal esophagus. The frequency of a hiatal hernia appears to increase with age.4

Esophageal acid clearance can be impaired in the elderly due to disturbances of esophageal motility and saliva production. In elderly persons, there is a significant decrease in the amplitude of peristaltic contraction and an increase in the frequency of nonpropulsive and repetitive contractions, as compared with younger individuals.9 Salivary production is slightly decreased with age, with a significantly decreased salivary bicarbonate response to acid perfusion of the esophagus.10 Many medications taken by elderly persons for comorbidities can affect esophageal motility as well as the LES. Also, many diseases that affect motility, such as Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus, appear with greater frequency with advancing age.

The role of delayed gastric emptying and duodenogastric reflux in elderly persons with GERD is uncertain. However, medications used in disease states more common in the elderly—such as calcium-channel blockers, benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, and antidepressants—may make these factors more important in the aging populations. Medications taken with greater frequency by the elderly also directly injure the esophageal mucosa, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), potassium tablets, and bisphosphonates. Gastric acid secretion does not decrease with age alone. However, factors that lead to atrophic gastritis, such as Helicobacter pylori, reduce gastric acid.11 Such factors associated with the age-related decrease in esophageal pain perception may explain the phenomenon of reduced heartburn symptom severity as individuals age. The feeling of reduced pain may in fact be a factor in the increased rate of GERD complications in the elderly, because acid injury can be more advanced without the usual warning symptoms.12

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn and acid regurgitation.5 Other common symptoms are water brash, belching, and nausea. Generally, these symptoms do not change with age, except for heartburn. Heartburn is characterized by epigastric and retro-sternal burning pain that may radiate to the neck, throat, and back. It can occur after large meals, exercise, or reclining. Dysphagia, difficulty in swallowing, is an important symptom that is increased in the older person. It may be related to several disease states that are more common in the elderly, such as oropharyngeal dysphagia, Parkinson’s disease, cerebrovascular disease, and diabetes. In persons with GERD, dysphagia usually occurs in the setting of longstanding symptoms and may progress to solids and, when severe, even to liquids. Other important symptoms that herald more severe disease are odynophagia (ie, pain upon swallowing), anemia, unexplained weight loss, and gastrointestinal bleeding. These portend a more severe problem, such as severe peristaltic dysfunction, peptic ulcer, esophageal stricture, or even cancer. Extraesophageal symptoms such as atypical chest pain, ear, nose, and throat (ENT) manifestations, and pulmonary problems, are common in the elderly, and will be further discussed below.13

COMPLICATIONS

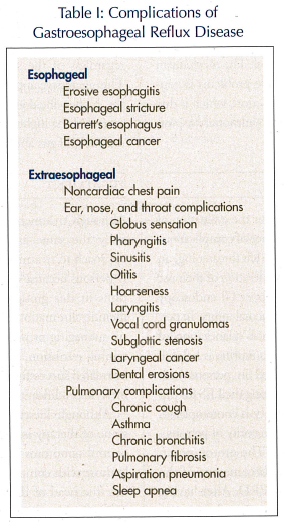

Complications of GERD are common in the elderly. Up to 20% of persons seeking medical care for GERD in the United States have complications.2 Severe illnesses can result from GERD. These disease states may be esophageal or extraesophageal in nature. Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux is associated with more severe manifestations.6-8 They may vary from minor problems of mild esophagitis to major life-threatening problems, such as recurrent pulmonary aspiration, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal cancer (Table I).14

Complications of GERD are common in the elderly. Up to 20% of persons seeking medical care for GERD in the United States have complications.2 Severe illnesses can result from GERD. These disease states may be esophageal or extraesophageal in nature. Nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux is associated with more severe manifestations.6-8 They may vary from minor problems of mild esophagitis to major life-threatening problems, such as recurrent pulmonary aspiration, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal cancer (Table I).14

Esophageal Complications

The most common complication of GERD is esophagitis. It may progress to severe erosions and ulcerations that can rarely produce severe hemorrhage.13 Esophageal stricture occurs in up to 10% of persons who have reflux esophagitis, especially in elderly men. Esophageal strictures are often associated with the use of NSAIDs, potassium tablets, and bisphosphonates. Treatment usually consists of esophageal dilatation and aggressive antireflux therapy.

An important and increasingly more common esophageal complication is Barrett’s esophagus, in which columnar epithelium replaces squamous epithelium in the distal esophagus. It occurs in approximately 10-15% of persons with GERD symptoms who undergo endoscopic examination.15 It is more common in elderly white men over the age of 60. Although its pathogenesis is uncertain, GERD appears to injure the squamous epithelium and promote epithelial repair by columnar metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa. The current treatment is similar to that for routine GERD.15 Barrett’s esophagus is a premalignant condition that is highly associated with the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and the gastric cardia. Endoscopy should therefore be considered in all elderly persons with chronic reflux symptoms. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is now the most common form of esophageal cancer and is among the fastest growing carcinomas by incidence in the United States.7 The incidence of adenocarcinoma in persons with Barrett’s esophagus is approximately 1% per year.15 These individuals typically present in the seventh or eighth decade of life with weight loss and dysphagia. Persons with Barrett’s esophagus must be evaluated with upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy and biopsy for the presence of dysplasia, which is a precursor of invasive cancer. Continued surveillance and aggressive measures in high-grade dysplasia are warranted and include endoscopic ablative techniques such as electrocautery fulguration, laser photoablation, photodynamic therapy, and even esophagectomy. Although the overall survival rate of persons with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is less than 10%, those with cancer identified in surveillance programs usually have higher survival rates.16

Extraesophageal Manifestations

Extraesophageal manifestations of GERD are more common in the elderly.17 Atypical noncardiac chest pain from GERD may often be indistinguishable from angina. Atypical chest pain has been related to GERD in up to 60% of cases, with 50% being related directly to reflux injury and 10% related to esophageal motility. It is estimated that 4-10% of patients presenting to an otolaryngology practice will have symptoms or findings related to GERD.18 Laryngitis is the most common ENT complication of GERD. In up to 10% of persons with hoarseness, acid peptic injury from reflux is the cause.19 Prolonged antireflux treatment may be necessary and is effective in these persons. However, prompt relapses do occur when therapy is discontinued. Acid injury also promotes the development of otitis, sinusitis, pharyngitis, vocal cord granulomas, subglottal stenosis, laryngeal cancer, and possibly dental problems such as dental erosions, which are noted with increasing frequency in persons with GERD. Pulmonary problems associated with GERD, such as asthma, chronic bronchitis, pulmonary fibrosis, aspiration pneumonia, and even sleep apnea, are seen more frequently in the elderly. Remarkably, chronic cough can be the only symptom of GERD in some persons. In up to 21% of persons with chronic cough, GERD is implicated as the cause, and antireflux therapy is often helpful. The mechanism involved in the development of these problems is neurally mediated reflex bronchoconstriction, which is due to esophageal irritation by acid and pulmonary aspiration of refluxed material.20

EVALUATION

Several diagnostic tests are available for the evaluation of GERD. Because of the higher incidence of complications in the elderly that may be severe and life threatening, an aggressive approach with earlier consideration of their use is warranted. Barium swallow and upper GI endoscopy are used to evaluate dysphagia and mucosal injury. In persons with atypical symptoms or when quantitation of reflux is required, ambulatory pH monitoring is helpful. Esophageal manometry is often used in persons with markedly atypical symptoms, for locating the LES for pH testing, and in those for whom surgery is contemplated. It is not useful for evaluation in the majority of persons.

Newer tests are now available.21 The proton pump inhibitor (PPI) test has evolved to become one of the most useful noninvasive tests for GERD. After having a baseline of chest pain in the previous 2 weeks, persons are given a course of high-dose PPI agent, such as omeprazole 60 mg per day for 7 days, and are observed for improvement in their clinical response.22 Multichannel intraluminal impedence with pH sensor allows the detection of pH episodes, irrespective of their pH values (acid and nonacid reflux). It is useful in the postprandial period, and in persons with persistent symptoms while on therapy and those with atypical symptoms. Diagnostic tests should be performed in persons in whom the diagnosis remains uncertain; in persons with atypical symptoms such as chest pain, ENT problems, or pulmonary complications; and in persons with symptoms associated with complications, such as dysphagia, odynophagia, unexplained weight loss, GI hemorrhage, and anemia.17 Tests should also be performed in persons prior to consideration of antireflux surgery and in persons who have an inadequate response to therapy, whether medical or surgical, or who have recurrent symptoms. In contrast to younger persons, endoscopy should be considered earlier as the initial diagnostic test in elderly persons with heartburn, regardless of the severity or duration of complaints. This aggressive approach may be warranted because of the higher incidence of cumulative acid injury over years and the higher incidence of complications of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer in the elderly.3

TREATMENT

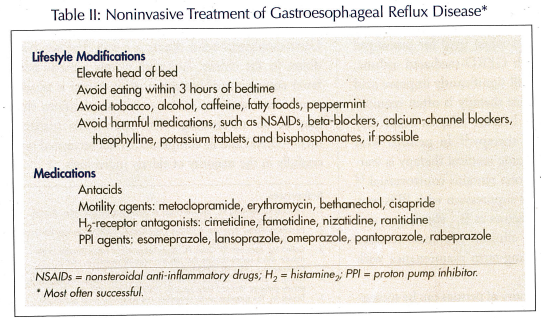

Although treatment of GERD in the elderly is essentially the same as in all adults, a more aggressive approach to treatment may often be necessary in elderly persons because of the higher incidence of complications in this group. The treatment goals for GERD include elimination of symptoms, healing of esophagitis, managing or preventing complications, and maintaining remission.23 The vast majority of persons can be treated successfully with the noninvasive methods of lifestyle modification and medication (Table II).

Although lifestyle modification remains a cornerstone of therapy in GERD, it may not be sufficient to control symptoms in the majority of persons, especially those with complications. Persons should try to elevate the head of the bed before going to sleep, avoid eating within three hours of bedtime, stop tobacco smoking, and change their diet to decrease fat and volume of meals and to avoid dietary irritants such as alcohol, peppermint, onion, citrus juice, coffee, and chocolate. Potentially harmful medications, such as NSAIDs, potassium tablets, bisphosphonates, beta-blockers, theophylline, and calcium-channel blockers, should be avoided when possible. If these agents must be continued, the regimen should be modified on an individual basis. Often, it may not be possible to avoid these medications due to comorbid conditions in the elderly.

Over-the-counter antacids and histamine2 (H2)-blockers on an as-needed basis may be helpful for individuals with mild disease. However, for the majority of persons, and certainly for those with complications, one must use prescription agents for more effective therapy, at least until symptoms are initially controlled.

Motility agents, such as cisapride, metoclopramide, erythromycin, and bethanechol, have helped somewhat to improve LES tone and esophagogastric motility in select persons. In persons with severe disease, success with these agents is limited. For persons with diabetes, cisapride and metoclopramide have been used with moderate success in improving gastric emptying and reducing GERD symptoms. However, cisapride is available only on a compassionate-use basis due to potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias. Metoclopramide must be used with caution in the elderly because it can cause side effects, such as muscle tremors, spasms, agitation, insomnia, drowsiness, and tardive dyskinesia, in up to one-third of persons.

Histamine2-receptor antagonists, including cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and nizatidine, are very helpful in persons with GERD by providing good acid suppression and symptom relief. They are remarkably similar in their action and equally effective at equivalent doses. However, high doses of up to four times daily may be necessary in some persons. Although these agents are safe in the elderly, reduced doses are necessary in renal insufficiency, which is more common in this population. In addition, H2-receptor antagonists may contribute to the development of delirium in this age group. Drug–drug interactions, especially with cimetidine, may be potentially harmful in elderly persons who often use medications that can be affected by metabolism of the hepatic cytochrome P-450 system (eg, warfarin, phenytoin, benzodiazepines, and theophylline). Side effects of these agents—especially cimetidine—are more common in the elderly. Central nervous system side effects, such as mental confusion, delirium, headache, and dizziness, are more common in the elderly. Anti-androgen side effects, such as gynecomastia and impotency; cardiac side effects, such as sinus bradycardia, atrioventricular block, and prolongation of the QT interval; and hematologic side effects, such as anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, have increased frequency in the elderly, especially in those with comorbid conditions. However, most side effects are reversible with dosage reduction or withdrawal of the drug.

Proton pump inhibitors, such as esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole, constitute the most effective therapy for GERD. Proton pump inhibitors provide excellent acid suppression and effective symptom relief. These agents are particularly useful in elderly persons who often require more acid suppression due to more severe disease or complications. In older individuals who are unable to swallow pills, capsules may be opened and the granules mixed in water or juice, or sprinkled on applesauce or yogurt. Lansoprazole also is available as an orally dissolving tablet, and both lansoprazole and omeprazole powders are available as oral suspensions, which may be useful for persons with swallowing disorders or those on tube feedings.

Relapses are common in elderly persons with GERD, especially in those with complications. Maintenance therapy is important. Long-term treatment with adequate doses of medication is the key to effective care in the elderly. For the majority of persons with peptic esophageal strictures, acid suppression and esophageal dilatation are effective therapies. Aggressive acid suppression is effective in the majority of persons with GERD-related chest pain. Such ENT problems as hoarseness have dramatic responses to these agents when used for prolonged periods. In persons with GERD-mediated asthma, H2-blockers and PPIs will significantly improve acid suppression. Maintenance therapy is often required in persons with GERD because relapses occur very soon after cessation of therapy.23 In persons with Barrett’s esophagus, chronic medical therapy is warranted, although its success remains controversial.12 Although profound acid suppression with PPIs may potentially affect such factors as B12 absorption and bacterial proliferation, clinical relevance remains uncertain. Therefore, long-term maintenance with PPIs is safe.24

Although the vast majority of persons can be successfully managed with medical therapy, invasive methods of surgery and endoscopic treatment of GERD may be warranted. Surgery is an option for some persons with GERD.25 Surgery is now more frequently contemplated because of the ability to perform antireflux surgery laparoscopically. It is indicated in persons with intractable GERD, difficult-to-manage strictures, severe bleeding, nonhealing ulcers, recurrent aspiration, and GERD requiring large maintenance doses of PPIs or H2-receptor antagonists. Barrett’s esophagus alone is not an indication for surgery. Given that there appears to be no more increase in postoperative morbidity or mortality in the elderly with this type of surgery, healthy elderly people should not be denied surgery on the basis of age alone.26 Careful patient selection with complete preoperative evaluation—including upper GI endoscopy, esophageal manometry, pH testing, and gastric emptying studies—should be done prior to surgery.

Endoscopic therapy of GERD is evolving. Implantation of Enteryx®, a biocompatible, nonbiodegradable polymer into the gastric cardia, appears to be effective for the treatment of GERD.27 The Stretta® Procedure, which delivers radiofrequency energy to the gastroesophageal junction, has been effective in reducing symptoms of GERD.28 In addition, endoscopically suturing below the gastro-esophageal junction is possible and has been used successfully to treat GERD.29 Further investigation and perfection of these techniques is warranted.

CONCLUSION

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a very common condition in the elderly. Although elderly persons have fewer complaints of heartburn, their disease is usually more severe and has more severe complications that may be life threatening. With appropriate management, GERD and its complications can be treated successfully in the majority of elderly individuals.