Medical Direction in Nursing Facilities: New Federal Guidelines

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

In his 1983 textbook Clinical Aspects of Aging, Dr. William Reichel1 outlines the history of the role of the nursing facility medical director, and the early attempts to mandate this role within federal regulation. Dr. Reichel reminds us that in 1970, a Salmonella epidemic in a Baltimore, MD, nursing home caused the deaths of 36 elderly residents. There was no state or federal requirement for nursing facilities to have medical directors at the time. In response to the Salmonella epidemic, the Maryland Medical Society developed an outline of responsibilities for nursing facility medical directors and mailed it out to each facility’s “principal physician,” with a directive implying that if it was not followed, the physician would in effect be guilty of poor medical practice.1 This may have been the first mandated role of a nursing facility medical director in the nation.

In 1971, President Nixon directed the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) to implement plans for upgrading substandard nursing facilities.1 As part of this plan, HEW requested that the American Medical Association sponsor seminars on the role of the medical director of skilled nursing facilities. The seminars were held in ten cities around the country, with 558 physicians and almost 1000 other health professionals in attendance. As a result of these seminars, in 1973 the American Medical Association published “Guidelines for a Medical Director in a Long-Term Care Facility,” which listed 15 functions of a medical director in order to help ensure the adequacy and appropriateness of the medical care provided to the residents.1 Also in 1973, HEW proposed a set of common standards for all skilled nursing facilities under Medicare and Medicaid. There was no requirement for a medical director within these standards. The American Medical Association was very vocal in its advocacy for a federal requirement mandating nursing facility medical directors. In 1974, regulations were approved, which required, as a condition of participation, that each skilled nursing facility retain a physician to serve as a medical director on at least a part-time basis.1

Once again in 1982, with new proposed regulations, the medical director mandate was deleted. The American Medical Association, the American Geriatrics Society, and a relatively new organization, the American Medical Directors Association, along with 34 other national organizations, protested the absence of a medical director role in the proposed regulations. It was felt that without a clear federal requirement for physician administrative input, that many, if not most, nursing facilities would not voluntarily hire a physician for this role, and that the residents would suffer from this absence. As a result, the medical director mandate was once again restored in federal regulation for skilled nursing facilities.1

In the 1980s, Drs. James Pattee and Thomas Altemeier of the University of Minnesota School of Medicine, began conducting research on the role of the nursing facility medical director, and also began a continuing medical education course offered in several cities around the country for training nursing home medical directors. In 1991, they convened an expert panel to develop a core curriculum for nursing facility medical directors.2 This curriculum served as the foundation for the American Medical Directors Association core curriculum program for nursing facility medical directors.

The current era of nursing facility regulation was ushered in by the passage of the nursing home reform amendments of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 (OBRA ’87). It was not until the implementation of OBRA ’87 in 1990 that all nursing facilities participating in Medicare and/or Medicaid were required to have a medical director, by making all facilities subject to the skilled nursing facility requirements.3 Although OBRA ’87 contained limited language about the requirement for a medical director, the presence of the interpretive guidelines for surveyors—which delved into many aspects of medical practice, such as guidelines for prescribing psychoactive medications—certainly brought the role of the medical director into a more critical realm for nursing facilities.3

REVISED REGULATIONS AND NEW SURVEYOR GUIDELINES

It is within this historical context that the revised CMS regulations for nursing facility medical director, (F 501) 483.75(i), have been published.4 The regulation itself is straightforward, and simply clarifies the expectations for the medical director to participate in the quality initiatives within the nursing home. It states as follows:

The intent of this requirement is that:

• The facility has a licensed physician who serves as the medical director to coordinate medical care in the facility and provide clinical guidance and oversight regarding the implementation of resident care policies;

• The medical director collaborates with the facility leadership, staff, and other practitioners and consultants to help develop, implement, and evaluate resident care policies and procedures that reflect current standards of practice; and

• The medical director helps the facility identify, evaluate, and address/resolve medical and clinical concerns and issues that:

-affect resident care, medical care, or quality of life; or

-are related to the provision of services by physicians and other licensed health care practitioners.4

The guidance to the surveyors that follows the actual regulatory language includes a clarification that the role of the medical director is distinct from that of the attending physician, and involves the coordination of facility-wide care, while the attending role is that of the care of individual residents. Several definitions are provided, such as what is meant by “current standards of practice.” The instructions to surveyors specifically refer the surveyor to the website of the American Medical Directors Association for clarification of the roles and responsibilities of the nursing facility medical director (www.amda.com). Specific instructions are given to the surveyor regarding how to evaluate the medical director’s participation in implementation of resident care policies and procedures, and the coordination of medical care. Specific references are made to books by Drs. James Pattee5 and Steven Levenson6,7 on medical direction in long-term care facilities.

The general instructions to the nursing facility surveyors are followed by an “investigative protocol” aimed at assisting the surveyor in determining whether the facility is in compliance with the regulations.4 An important part of the investigative protocol is whether the medical director is available during the survey to respond to surveyor questions. The surveyor is also instructed as to how to question administrative staff regarding the medical director’s role. Based upon these interviews, and reviews of policies and procedures and actual resident care, the surveyor must decide whether the facility is in compliance with federal requirements for the nursing facility medical director (Tag F501). In determining compliance, the surveyor is given the following criteria:

The facility is in compliance if:

• they have designated a medical director who is a licensed physician; and

• the physician is performing the functions of the position; and

• the medical director provides input and helps the facility develop, review, and implement resident care policies, based on current clinical standards; and

• the medical director assists the facility in the coordination of medical care and services in the facility.4

The surveyor is given a list of criteria that may indicate noncompliance on the part of the facility with respect to the function of the medical director (eg, if there is no system in place to monitor the performance and practices of the health care practitioners).

Once the surveyor determines if a deficiency will be assigned for noncompliance with the regulation, then the next step is to determine the scope and severity of the deficiency. Severity is determined by whether there is the presence of harm or negative outcomes, or the potential for harm or negative outcomes, that results from the noncompliance.4

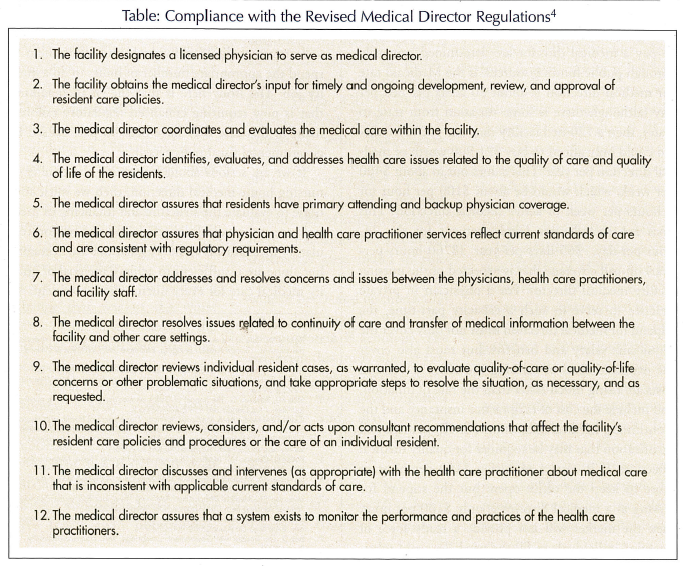

The Table lists some actions that medical directors can take to effectively respond to these revised regulations and new surveyor guidelines.

DISCUSSION

There are many who view the inclusion of the new guidance to surveyors for the enforcement of the revised medical director regulations as a natural progression of the history of nursing home reform with its origins in the 1970s and, in fact, as a victory for those who champion the role of the nursing facility medical director in improving the quality of nursing home care. Proclamation of victory, however, may be shadowed by the defeat of nonregulatory mechanisms, such as professionalism and market forces. When we must resort to command/control regulatory mechanisms to achieve a purpose, we admit defeat in a sense.8

To be truly effective, this regulatory mandate must be accompanied by the appropriate funding of the role of medical director. Since more than half of nursing home residents are funded through the Medicaid program, the stipends that facilities can afford to pay a medical director are determined primarily through public funding sources. If the Medicaid rate for medical direction is about 50 cents per bed per day (although there is some variation from state to state), then a 120-bed facility that was 100% Medicaid could only afford to buy $21,900 worth of medical direction per year. This comes out to about $400 per week, which would be about $100 per hour for 4 hours per week of active medical direction. This does not include any reimbursement for the 24-hour-per-day, 365-days-per-year (8760-hours-per-year) on-call coverage that is expected of the nursing facility medical director. For a physician in private practice to serve in such a capacity part-time, the stipend for medical direction must not only cover the physician’s salary and benefits, but must also cover the overhead costs of running the office. Overhead costs are rising much faster than the rate of inflation, and include the cost of malpractice insurance and the Continuing Medical Education (CME) courses and certification that may be required for quality medical direction. If it costs a physician $180 per hour or more to keep the office open, but the stipend for serving as a medical director is only $100 per hour, then the market will not provide a ready force of qualified individuals to fill the need. To avoid subsidizing private practice overhead costs, some nursing facilities are hiring medical directors who perform only administrative work serving multiple facilities, and who do not have office practices. Whether this leads to improved medical direction or to cost savings has not yet been demonstrated.

During the historical periods of the 1970s and 1980s, there was concern that the private sector would not want to pay for nursing home medical direction, although it was viewed by dozens of national organizations as a necessity for the health and safety of the residents. Therefore, the call was to mandate the role through federal regulation. An appropriate role for federal regulation is to make corrections that result from a market failure.9 Since the federal and state governments through the Medicaid program have become the principal payor source for long-term care in the interim, the question is whether Medicaid can set a medical director rate that will attract qualified individuals and allow them to spend the appropriate number of hours to do a quality job. The irony here is that the “market failure” that is now requiring enhanced regulatory enforcement in this case may have been in part caused by governmental fiscal policy itself.

If we are serious about improving the quality of nursing home medical direction, then we must continue to evaluate the structure and financing of medical care and medical direction, and not rely on regulatory mechanisms alone. Regulations are necessary, but alone are insufficient to achieve the goal of quality medical care for every nursing home resident.