Common Visual Problems: Symptoms and Treatment, Part II

Part I of this article appeared in the August issue of the Journal.

THE CHALLENGE

In the year 2000, almost one million Americans over age 40 years were deemed “blind” and 2.4 million had “low vision.” The incidence of both blindness and low vision in Americans is projected to increase dramatically by the year 2020. Persons over age 80 years accounted for more than two-thirds of the observed blindness, and, as we know, this more elderly group is the fastest-growing segment of the U.S. population.1

In a 2-year study of individuals age 65-84 years, 25% suffered “significant vision loss” over that interval (visual acuity diminished in 25%; contrast sensitivity and visual field loss occurred in 10%). In a cohort of individuals over age 85 years, one-half had better than 20/40 acuity, but with low contrast and “veiling glare,” 75% had their acuity diminished to less than 20/200; 50% of these individuals had no stereopsis. “Glare recovery” took longer than 2 minutes versus 15 seconds for those under age 65 years, and visual fields tested with “divided attention” (ie, a central distracting task) is about one-half the expanse of that for individuals younger than age 65 years.2 In addition, this loss of visual function is often compounded by other age-related disabilities. Of special note is the fact that high-contrast visual acuity, the most commonly used measure of visual function, is the slowest and probably the least sensitive measure of visual function to decline with age.3-5

Poor visual function has deleterious effects on vocation and avocations, driving ability (especially at night), and routine activities of daily living. Positive correlations have been documented between vision loss and auto accidents, loss of employment, increasing dependence on others, social isolation, depression, personal accidents, hip fractures, and ultimately, mortality.6-12

AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION

Dramatically increased awareness of macular degeneration among our elderly population has resulted in a great deal of physician time, both ophthalmologist and primary care provider, counseling justifiably concerned individuals about this condition, its treatment, and potential avoidance. Macular degeneration is the leading cause of irreversible vision loss in the developed countries, with a steep increase in incidence with aging. The frequency of macular degeneration in the 50- to 64-year-old age group has been estimated at anywhere from 1-8%. About 30% of those over age 70 years have some sign of macular degeneration, while in those over age 85 years, the incidence climbs to 53%. There are over 6 million individuals in the United States afflicted with this disorder.13,14

Some of the confusion and significant variation in incidence numbers results from a lack of standardization and definition. Many individuals in the older age group exhibit macular degeneration in the form of asymptomatic drusen or retinal changes that are characteristic of the disorder, but with no noticeable impact on visual function. Others may have minimal reduction of vision, but are not categorized as macular degeneration by some investigators until the reduction in vision has exceeded a certain threshold.

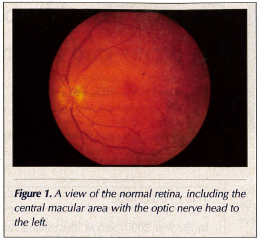

As a brief reminder of the anatomy and physiology of the retina and macula, it is worth recalling that the macular area, which is responsible for keen vision and acuity, represents only the central 2-millimeter diameter of the retina (about the diameter of the optic nerve head), located at fixation where objects of regard fall in direct focus (Figure 1). Anywhere outside this tiny central focal point of the retina, the resolving capacity of the photoreceptors is 20/200 or less, which decreases the more peripheral in the retina the light rays strike. Consequently, without this tiny central fixation point in the retina, reading and detailed visual tasks of any type, such as recognizing faces at any significant distance, become virtually impossible without magnification or other visual aids.

As a brief reminder of the anatomy and physiology of the retina and macula, it is worth recalling that the macular area, which is responsible for keen vision and acuity, represents only the central 2-millimeter diameter of the retina (about the diameter of the optic nerve head), located at fixation where objects of regard fall in direct focus (Figure 1). Anywhere outside this tiny central focal point of the retina, the resolving capacity of the photoreceptors is 20/200 or less, which decreases the more peripheral in the retina the light rays strike. Consequently, without this tiny central fixation point in the retina, reading and detailed visual tasks of any type, such as recognizing faces at any significant distance, become virtually impossible without magnification or other visual aids.

While there are numerous types of macular degeneration, the most common in the age-related category are the so-called “dry” type, constituting almost 90% of the cases, and the “wet” type, or neovascular form of macular degeneration, which represents the remaining 10%. There is a dramatic increase in incidence of both of these types of macular degeneration with aging.

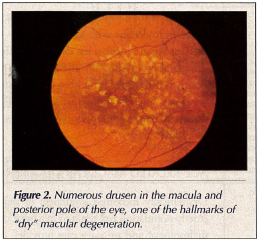

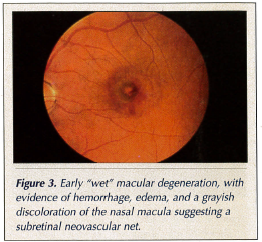

We distinguish between the wet and dry types of macular degeneration by clinical observation, often better defined by ocular angiography, using most commonly fluorescein or similar fluorescent dyes injected intravenously while photographs are taken as the dye passes through the choroidal and retinal vasculature. Abnormal new blood vessels growing under and into the retina—the hallmark of wet macular degeneration—can thus be identified and localized. At the same time, the lack of these vessels, the extent of deterioration of photoreceptors, and the underlying retinal pigment epithelium, which nourishes and supports the photoreceptors, can be determined. Drusen, one of the most common (though by no means the only) sign of age-related macular degeneration appear as tiny yellow circumscribed spots deep in the retina, histopathologically being excrescences of Bruch’s membrane, the semipermeable barrier between the choriocapillaris and the retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 2). When wet macular degeneration develops, the abnormal new vessels invading the retina lack the “blood retinal barrier” of the normal retinal vessels. These abnormal vessels leak, causing edema, hemorrhage, blood in and under the retina, and ultimately fibrosis, in the process destroying the photoreceptors and central vision (Figure 3).14,15

We distinguish between the wet and dry types of macular degeneration by clinical observation, often better defined by ocular angiography, using most commonly fluorescein or similar fluorescent dyes injected intravenously while photographs are taken as the dye passes through the choroidal and retinal vasculature. Abnormal new blood vessels growing under and into the retina—the hallmark of wet macular degeneration—can thus be identified and localized. At the same time, the lack of these vessels, the extent of deterioration of photoreceptors, and the underlying retinal pigment epithelium, which nourishes and supports the photoreceptors, can be determined. Drusen, one of the most common (though by no means the only) sign of age-related macular degeneration appear as tiny yellow circumscribed spots deep in the retina, histopathologically being excrescences of Bruch’s membrane, the semipermeable barrier between the choriocapillaris and the retinal pigment epithelium (Figure 2). When wet macular degeneration develops, the abnormal new vessels invading the retina lack the “blood retinal barrier” of the normal retinal vessels. These abnormal vessels leak, causing edema, hemorrhage, blood in and under the retina, and ultimately fibrosis, in the process destroying the photoreceptors and central vision (Figure 3).14,15

Treatment of wet macular degeneration consists of laser therapy. Conventional laser therapy is capable of coagulating and destroying foci of the new abnormal vessels, but unfortunately it destroys the overlying retina as well. Consequently, conventional laser therapy has not been useful in the treatment of wet macular degeneration, in which the abnormal blood vessels involve fixation, directly under the fovea, the central portion of the macula (90% or more of the cases!). Some years ago, photodynamic therapy was developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In this therapy, a dye that has a selective affinity for the growing endothelial cells of the abnormal new vessels is injected and subsequently illuminated with a specific wave-length laser “tuned” to the dye’s absorption. The result is coagulation within the abnormal new vessels, sparing the overlying retina. While, in theory, this sounds like the perfect “magic bullet,” in practice it often requires numerous treatment sessions and has had a variable success rate. Nonetheless, it does result in a definite reduction in the incidence of visual loss over time, and represents a statistically proven treatment benefit for those patients with subfoveal neovascularization, previously untreatable.16,17

Treatment of wet macular degeneration consists of laser therapy. Conventional laser therapy is capable of coagulating and destroying foci of the new abnormal vessels, but unfortunately it destroys the overlying retina as well. Consequently, conventional laser therapy has not been useful in the treatment of wet macular degeneration, in which the abnormal blood vessels involve fixation, directly under the fovea, the central portion of the macula (90% or more of the cases!). Some years ago, photodynamic therapy was developed and approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In this therapy, a dye that has a selective affinity for the growing endothelial cells of the abnormal new vessels is injected and subsequently illuminated with a specific wave-length laser “tuned” to the dye’s absorption. The result is coagulation within the abnormal new vessels, sparing the overlying retina. While, in theory, this sounds like the perfect “magic bullet,” in practice it often requires numerous treatment sessions and has had a variable success rate. Nonetheless, it does result in a definite reduction in the incidence of visual loss over time, and represents a statistically proven treatment benefit for those patients with subfoveal neovascularization, previously untreatable.16,17

The first example of an exciting new class of therapy for neovascular macular degeneration has been approved by the FDA. This treatment consists of intravitreal injections of inhibitors of the neovascular (endothelial) growth factors. The FDA trial results look very promising. Clinical practice patterns and protocols for its use will be developed, as other candidate drugs with other modes of administration emerge from the pipeline.18

The important message is that effective treatment of wet macular degeneration requires early detection before significant, irreversible damage to retinal photoreceptors and architecture has occurred. The early symptoms of macular degeneration must be recognized by the patient and the treating physician. Distortion in or near the central vision and fixation point often reflects retinal edema from leaking new vessels. Similarly, subtle vision loss, or symptomatic central or paracentral relative or absolute scotomas, may be an indication of macular degeneration. For patients at risk, most ophthalmologists will give them an Amsler grid, a simple piece of graph paper with a central fixation dot, which the patient can observe each morning with each eye individually, assuring that no change has occurred.

Of course, prevention is always worth more than our best treatment. With this in mind, a long-term study was undertaken by the National Eye Institute to evaluate the potential value of antioxidant vitamins and minerals.19 Begun approximately 10 years ago, this study evaluated vitamin C 500 mg, vitamin E 400 international units, beta-carotene 15 mg, and zinc oxide 80 mg, combined with copper oxide 2 mg per day (added to prevent potential copper deficiency due to competitive absorption with zinc). The study was stopped after 7 years, when positive data showed the risk of developing advanced macular degeneration in a high-risk group was reduced by 25%, and the risk of vision loss in the same group was reduced by nearly 20%. While no apparent effect was noted in patients with early macular degeneration or no macular degeneration over the 7.3-year time frame of the study, the control group within this arm of the study showed no significant progression, and therefore no treatment benefit could be assessed. The risks of this high-dose regimen consisted of increased rate of urinary tract infection requiring hospitalization in the group taking zinc (7.5% vs 5% in the control cohort), a slightly higher risk of lung cancer in smokers taking beta-carotene (a curious result that has been confirmed in other unrelated studies), and the potential for yellowing of skin in patients taking beta-carotene. The more recent concerns raised about excess vitamin E were not noted in the results of this large study, and have not, as yet, been introduced into any new widespread practice pattern or consistent, informed advice. This vitamin regimen, known as the Age-Related Eye Disease Study (AREDS) formula, has been in common use by ophthalmologists for patients who fall into the appropriate risk categories.19,20 Lutein, flavonoids, and other substances that may have some prophylactic value, have also been suggested since this study was initiated, and are currently under investigation.21-25

With most problems in medicine for which our accepted treatments lack complete or dramatic efficacy, many “alternative” treatments exist in the marketplace. Our desperate patients are susceptible to the claims for many alleged treatments, most of which are probably harmless and simply result in unnecessary cost to the patient. But most, if not all, ophthalmologists have seen some unproven treatments actually hasten visual loss, if not from their own damaging effects, then from the patient’s lack of attentiveness to our present best clinical practices that can offer treatment benefit and limit the extent of visual loss from this devastating problem.26

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

More than 14 million Americans are suspected of having diabetes, but only about half of these individuals are actually aware of their condition. There are more than 65,000 new cases of proliferative retinopathy, and 8000 new cases of diabetic blindness each year. Over 90% of the patients experiencing diabetic blindness could have had useful vision preserved with timely diagnosis and institution of treatment.27-31

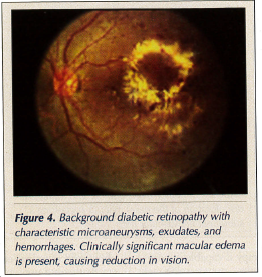

Diabetic retinopathy is divided into two basic types: background and proliferative. Background diabetic retinopathy is characterized by microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and exudates. Macular edema is the leading cause of visual loss in diabetics. While macular edema may be mild or quite extensive, with symptoms varying from minimal visual loss to a profound decrease in acuity, macular edema represents a validated indication for treatment in background retinopathy (Figure 4). In the majority of patients who do not have significant macular ischemia, laser treatment can limit the visual loss and may result in significant improvement in vision.32,33

Diabetic retinopathy is divided into two basic types: background and proliferative. Background diabetic retinopathy is characterized by microaneurysms, hemorrhages, and exudates. Macular edema is the leading cause of visual loss in diabetics. While macular edema may be mild or quite extensive, with symptoms varying from minimal visual loss to a profound decrease in acuity, macular edema represents a validated indication for treatment in background retinopathy (Figure 4). In the majority of patients who do not have significant macular ischemia, laser treatment can limit the visual loss and may result in significant improvement in vision.32,33

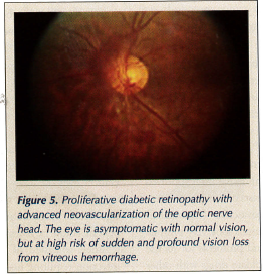

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy occurs when significant ischemia and capillary closure result in abnormal new blood vessel growth out of the retina or optic nerve head and into the vitreous cavity (Figure 5). This neovascularization is quite fragile; the vessels leak and hemorrhage. Hemorrhaging into the vitreous cavity or over the surface of the retina can result in permanent scarring, profound loss of vision, and total blindness due to traction retinal detachments. The important feature to recognize is that even advanced proliferative diabetic retinopathy with extensive neovascularization can be completely asymptomatic until a sudden vitreous hemorrhage and vision loss occur. Panretinal  photocoagulation with laser will prevent severe vision loss in the significant majority of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. For those patients who have already suffered vitreous hemorrhage that has not cleared, and/or traction retinal detachments, invasive vitreous microsurgery can be performed, but carries much greater morbidity and risk of significant visual loss than early diagnosis and simple outpatient laser treatment.34,35

photocoagulation with laser will prevent severe vision loss in the significant majority of patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. For those patients who have already suffered vitreous hemorrhage that has not cleared, and/or traction retinal detachments, invasive vitreous microsurgery can be performed, but carries much greater morbidity and risk of significant visual loss than early diagnosis and simple outpatient laser treatment.34,35

Of particular importance to primary care specialists and endocrinologists is the fact that proliferative diabetic retinopathy, with or without symptoms, represents a very important risk factor for such systemic vascular complications of diabetes as myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accidents, peripheral vascular disease leading to amputation, and nephropathy. Hypertension, increased blood lipid levels, and proteinuria are associated with the development of proliferative retinopathy.36

While diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness in the working age population, it represents a very significant disease in our increasing elderly population as well. Consequently, for the older population, we recommend a very careful dilated retinal evaluation at the time of diagnosis of diabetes, and at yearly intervals thereafter in order to make a timely diagnosis and institute appropriate therapy before irreversible visual loss or blindness occurs. Again, we can prevent over 90% of diabetic blindness through screening, leading to early diagnosis and institution of appropriate treatment.

DRY EYE DISEASE

Dry eye disease may seem like a trivial problem that hardly deserves inclusion in this discussion of serious blinding eye disease. Dry eye disease, however, may result in serious vision loss and even blindness from secondary infection; although this outcome is fortunately rare. But dry eye disease is an underrecognized and underappreciated disorder from which many of our elderly patients suffer significantly. There are actually millions of patients afflicted with dry eye disease worldwide. Approximately 15% of individuals over 65 years of age have some dry eye symptoms. Only a small percentage of these patients have systemic immune disorders and dry mouth associated with dry eye, which would lead to the diagnosis of Sjogren’s syndrome, in general, the more severe form of this ocular disease.

As with the other ocular disorders discussed in this article, the prevalence of dry eye disease increases with age. Approximately 6% of women over age 50 years and 10% of women over age 75 years suffer from this problem. In the U.S., it is estimated that 3.3 million women have dry eyes. Approximately 20% of the overall population with dry eyes is male.37-40

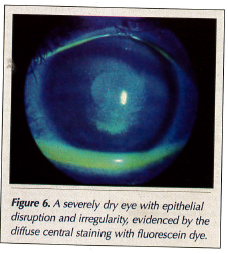

The symptoms include any or all of the following: ocular discomfort, a feeling of dryness, burning, stinging, chronic foreign body sensation with a gritty feeling, stickiness, significant photophobia, itching, and chronic redness. As a result of a poor tear film and disruption of the normally clear surface of the cornea, variable blurring occurs (Figure 6).

The symptoms include any or all of the following: ocular discomfort, a feeling of dryness, burning, stinging, chronic foreign body sensation with a gritty feeling, stickiness, significant photophobia, itching, and chronic redness. As a result of a poor tear film and disruption of the normally clear surface of the cornea, variable blurring occurs (Figure 6).

Essentially, half of this large group of patients reports that dry eyes affect their normal activities a great deal. A similar percentage feels that dry eyes affect their reading ability, and one-third of patients feel that dry eyes affect their ability to use a computer.41,42 If untreated, the dryness and disruption of the protective surface epithelium of the cornea renders these patients more susceptible to serious and sight-threatening corneal infections and ulcers.

While traditional treatment has consisted of over-the-counter lubricants known as “artificial tears,” in more significant cases these drops are combined with gels or ointments for nighttime use, and with various measures to promote tear conservation. Exciting new therapeutic modalities have recently been introduced. With the recognition that inflammation represents a very significant part of the vicious cycle of dry eye disease, anti-inflammatory agents have become a more significant and common adjunct to the treatment regimen. Topical cyclosporine eye drops have recently been approved by the FDA, and have been used very successfully in a significant percentage of patients, reducing their dependence on frequent application of artificial tear drops for relief of symptoms and preservation of corneal integrity.42-46

Amazingly, a study looking at the “utility” value of the symptoms of dry eye disease on lifestyle found that patients with moderate dry eye felt the condition was equivalent, in effect, to moderate angina.47 Consequently, appropriate early and accurate diagnosis of dry eye disease—avoiding the very frequent misdiagnosis and treatment with medications that often exacerbate the problem—leads to significant improvement for these patients’ visual functioning, lifestyle, and general well-being.47-51