Perioperative Care for Geriatric Patients

INTRODUCTION

Over half the population of elderly will require surgery at least once in their lifetime.1 Fifty years ago the prevailing wisdom was that surgery in the elderly should be confined to only those cases that were absolutely necessary. However, the dramatic improvements in surgical techniques, anesthetic techniques, and intensive care have made elective surgery in the elderly a commonplace event. Despite these advances, surgery in the elderly remains riskier than in younger age groups. Medicare data indicate that there is increasing mortality associated with increasing age for major vascular and cancer surgery.2 For example, pneumonectomy and mitral valvuloplasty had twice the mortality in the over-85 age group as in those age 65-69. However, there is debate as to whether it is age or coexisting disease that is responsible for this mortality. Studies that factor comorbidities into their analyses indicate that age primarily increases risk via an interaction with comorbid disease, and that age is not a major independent predictor of mortality.3

In addition to comorbidities, there are also unavoidable physical and physiological changes that occur with age and that must be considered in the perioperative period. This article will explore the care of the elderly before, during, and after surgery, with an emphasis on the interdisciplinary nature of this care and the role of the caregiver in the perioperative period.

THE PREOPERATIVE PERIOD

The most important general principle of the physiology of aging is that the aging process generally does not compromise the basal functioning of the various organ systems. However, age definitely decreases functional reserve and adversely affects one’s ability to cope with physiological stress.

Assessment of the Patient

The physiological changes that accompany aging, when superimposed upon pre-existing comorbidities, can make the geriatric surgical patient very complex to manage. It is no surprise, therefore, that the preoperative assessment of the patient should be painstakingly thorough. There are currently no accurate methods to predict which patient will have a given complication. However, there are a few crucial elements to the preoperative preparation that, when taken together, can aid in the management of the elderly patient. These elements are risk stratification, functional assessment, preoperative testing, and preoperative optimization.

Risk Stratification. The physiologic changes associated with aging predispose the geriatric population to rather unique risks that would presumably be nearly absent in a younger population. These include congestive heart failure, cardiac ischemia, aspiration, delirium, pneumonia, and urosepsis. At present, risk stratification is the result of preoperative evaluation and testing, rather than the tool used to guide the preoperative evaluation and testing, and overall risks are assessed on a patient-by-patient basis. Outcome studies for specific geriatric age groups would be very useful for advancing the ability to evaluate risks in these patients.

Functional Assessment. Changes in health care and longevity have resulted in a population of geriatric patients who are more diverse than ever before. One can age without frailty or can be frail without being old. The concept of frailty is often associated with decreased muscle mass, weight loss with or without malnutrition or undernutrition, decreased strength, decreased exercise tolerance, slowed motor performance and longer reaction time, decreased balance and proprioception, altered gait, low physical activity, and vulnerability to stressors. However, frailty may also involve the decline in homeostatic regulatory systems, which results in decreased physiologic reserve. We still have much to learn about the preoperative assessment of varying degrees of frailty and how this frailty directly impacts patient outcome. Curiously, a very simple test appears to be useful in assessing perioperative risk. Inability to exercise to a heart rate of at least 100 beats per minute has been associated with increased risk of both cardiac and pulmonary complications with surgery.4

Specific Disease States and Implications. Most medical conditions interact with the effects of aging to increase risk synergistically.3 A comprehensive review of all diseases and their effects on perioperative risk in older patients is beyond the scope of this article, but a few entities are worth review. Chronic lung disease due to smoking or other toxic exposure diminishes pulmonary reserve and increases the likelihood of pulmonary complications, but pulmonary function tests do not provide much predictive value beyond what can be determined from the history and assessment of functional activity.5 However, baseline pulmonary testing may prove to be useful postoperatively to determine the degree to which the patient has recovered.

Clearly, active signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure constitute high risk and preclude elective surgery, but there is little evidence that poor baseline left ventricular function and stable, controlled heart failure represent great risk. The best evidence comes from vascular surgery where patients with low baseline ejection fractions (< 35%) did not have increased risk of perioperative myocardial infarction or death, but did have increased long-term mortality over 20-month follow-up.6 Although arrhythmias are common in older patients, ventricular ectopy and all degrees of heart block appear to carry little additional risk to the patient, provided these problems are not in conjunction with other serious heart problems. Atrial fibrillation may be an exception, not because of tachycardia (which should be preventable), but because of the associated problems of stroke and anticoagulation. Perioperative stroke is more common in patients with atrial fibrillation, and preventing thromboembolic stroke is difficult given the need for adequate coagulation after surgery. However, stopping chronic warfarin or antiplatelet therapy for a few days before surgery appears to be safe. Postoperative onset of atrial fibrillation is more common in older patients, and especially common after cardiac or thoracic surgery.7

Preoperative Testing and Optimization. The majority of preoperative tests performed in the general population are not indicated or necessary, and there is some evidence that this generalization also applies to the geriatric population. Even if routine screening tests have a higher yield in the elderly, it is uncertain whether such testing leads to improved outcomes.8,9 The choice of what to test for, what to manage, and how to manage it really depends on disease severity, how stressful the surgery is expected to be, and the potential negative impacts from any interventions. For example, a patient with known coronary artery disease may well benefit from preoperative beta-blockade prior to elective orthopedic surgery, but the severity of underlying disease would need to be quite high before the risks of coronary artery bypass grafting would be warranted.

At a minimum, the patient will require a preoperative visit with both the surgical and the anesthesiological services. Risk stratification and functional assessments will help to guide these practitioners in deciding how to improve the patient’s medical condition prior to surgery. It is at this point that communication between the providers, the patient, and the patient’s family and other caregivers becomes a crucial factor in their management. The more information that is available to these providers during their preoperative evaluations, the less likely it is that additional consultations will be needed.

At times, however, an elderly patient will arrive at the preoperative clinic with no clear idea of what surgical procedure will be performed, when it will be performed, and why it will help them. Others arrive without a list of the medications they take and with an unclear idea of why the medications were prescribed in the first place. Sometimes the patient has a different physician for each medical problem, with no single identifiable primary caregiver who coordinates the various treatments into a single, unified care plan. In cases such as these, a preoperative medical/geriatric consult provides an opportunity for the patient to be fully evaluated and have care optimized.

A geriatrician is far more skilled and experienced at cognitive testing, evaluation of functional status, coordinating home care or rehabilitative services in the postoperative period, and managing chronic disease. For the truly complex patient, a geriatrician can be a helpful advocate by coordinating meetings between the various services, making sure that everyone understands the goals and treatment plan, and helping the patient (and family) avoid unrealistic expectations.

A primary care physician can also lead discussions about advance care directives and do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders. Many patients choose not to undergo resuscitation when they have a terminal illness or when they believe that there is a high likelihood that they might remain permanently incapacitated. However, an intraoperative cardiac arrest is often the result of a known (and reversible) event such as hypovolemia, a drug side effect, or an electrolyte imbalance, and the prognosis is exceptionally good in this setting. Therefore, it is important to review DNR orders during the preoperative evaluation, since it is often appropriate to attempt resuscitation in the unique setting of the operating room. These discussions can result in insightful discourse and can alleviate stress and worry about respect for the patient’s autonomy.

THE INTRAOPERATIVE PERIOD

Physiology

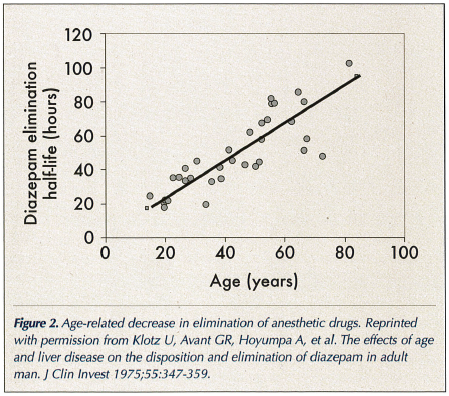

The physiology of the aging process makes the geriatric patient less able to compensate for perioperative stress, even when that patient is fit and without coexisting diseases. Since most healthy elderly patients have no noticeable alteration of baseline function, it can be nearly impossible to predict the effects of surgical stress on a given patient. However, normal aging makes hypotension, hypoxia, hypercarbia, low cardiac output, and altered fluid regulation more likely to develop in the perioperative period (Table I). Anesthetic drugs lower sympathetic tone and cause myocardial depression, and this frequently leads to hemodynamic instability during surgery. The physiologic changes related to aging also make it more difficult for the patient to tolerate the inevitable shifts in intravascular volume that accompany surgical procedures. Surgical trauma shifts fluid into the extravascular compartment (“third spacing” of fluid). Inadequate volume replacement can cause hypovolemia and decreased cardiac output. However, even judicious fluid replacement can cause difficulty when the patient begins to mobilize the third space fluid, because this mobilization may result in congestive symptoms when coupled with the normal vascular stiffness and diastolic dysfunction associated with aging. It is more effective to anticipate this as a normal postoperative process and treat it appropriately than to attempt to assign blame for its occurrence.

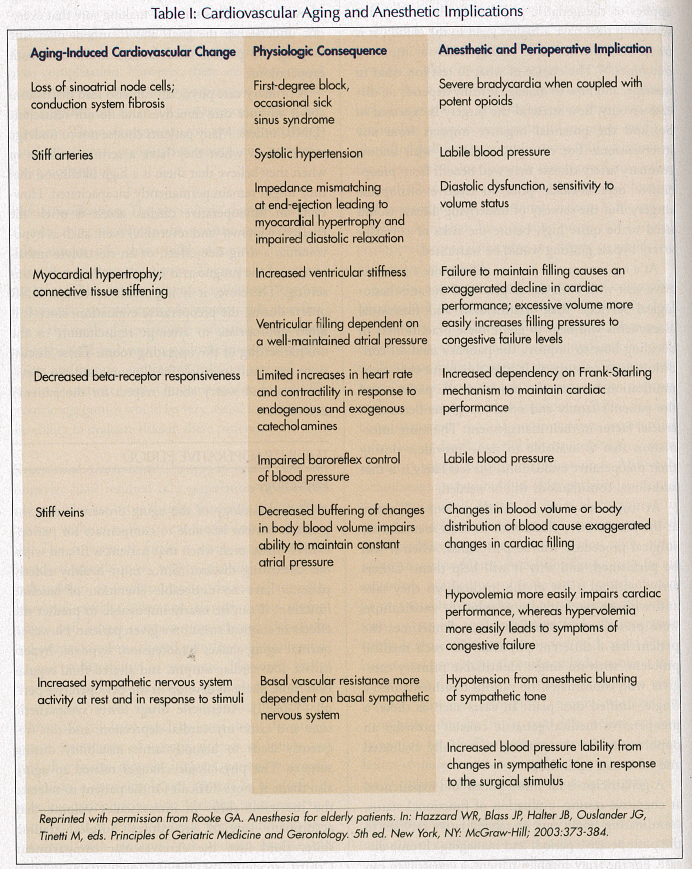

Pharmacology

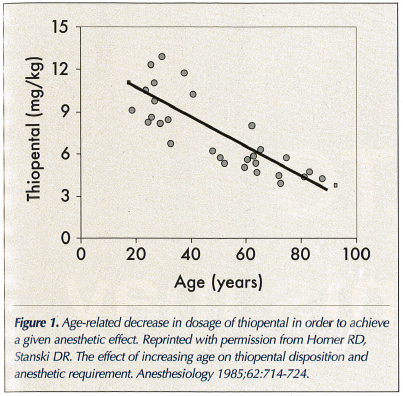

Much has been made of the increased sensitivity of the elderly to various drugs used during anesthesia. It is well known that there is an age-related decrease in dosage of thiopental and other drugs in order to achieve a given anesthetic effect (Figure 1).10 The reasons for this initial increased bolus effect include decreased protein binding, decreased total body water, decreased cardiac output resulting in slower redistribution of drug, and increased brain sensitivity to drugs. The overall effects are higher initial blood levels and target organ levels of drug. There is also an age-related decrease in elimination of many anesthetic drugs (Figure 2).11 This is the result of decreased clearance coupled with an increased volume of distribution. Clearance is decreased as a result of age-related decreases in hepatic blood flow, hepatic mass, and glomerular filtration rate. The volume of distribution is increased because of the higher percentage of body fat and the lower albumin levels that occur with aging.

Choice of Anesthetic Technique

Factors influencing the choice of anesthetic technique are numerous and complex, but when both regional and general anesthetics are appropriate, the choice is usually guided by outcomes that involve the incidence of serious adverse events. Initial small, randomized trials showed that regional anesthetics had some benefits for pulmonary and cardiac outcomes. However, subsequent large randomized trials have failed to confirm these benefits.12 Furthermore, postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction have not been found to be more common after general anesthesia when compared to regional anesthesia.13,14

Surgical Stress, Inflammation, and Immunity

Anesthesia and surgery are associated with a dramatically increased inflammatory response accompanied by a suppression of cell-mediated immunity.15,16 The magnitude of these changes can be affected by the length and invasiveness of the surgical procedure, the degree of preoperative anxiety experienced by the patient, and the severity of postoperative pain. Genetic background may also influence the perioperative inflammatory response.17 Furthermore, the normal age-related changes in sex steroid levels and the cellular damage associated with senescence may put geriatric patients at an increased risk for exaggerated inflammatory responses or immunosuppression. These changes in inflammation and immunity have implications for our ability to assess risk and improve outcomes in the elderly.

A number of the inflammatory mediators present in atherosclerosis are also released during the perioperative period.18 Many of the medications used to treat atherosclerosis have anti-inflammatory properties, including aspirin, statins, beta-blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors.18-20 In fact, the beneficial effects of beta-blockade on postoperative cardiac risk may have more to do with their substantial anti-inflammatory properties than their effects on hemodynamics.20 There is also a link between inflammation and cancer. Many cancers arise from areas of chronic infection and inflammation, and may require a pro-inflammatory milieu to support their continued growth.21 Chronic aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug usage is associated with decreased incidences of some tumors.22 Furthermore, there has been a demonstrated link between surgery and an increased incidence of tumor metastasis.23 The reduced lymphocyte counts and function after surgery could result in impaired tumor cell detection and elimination. Minimally invasive surgical techniques may have less of a negative impact on the immune system, making them even more attractive for the elderly. One can speculate that blockade of inflammatory mediators might further reduce perioperative adverse events.

THE POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD

Postoperative Complications

Although it is common for patients and their families to worry about complications and death while the patient is in the operating room, the vast majority of adverse events occur in the postoperative period. In fact, when compared to the intraoperative period, morbidity and mortality rates are doubled in the first 24 hours and are tenfold higher over the remainder of the first postoperative week.24 The most common and worrisome complications are pulmonary and cardiovascular in origin.

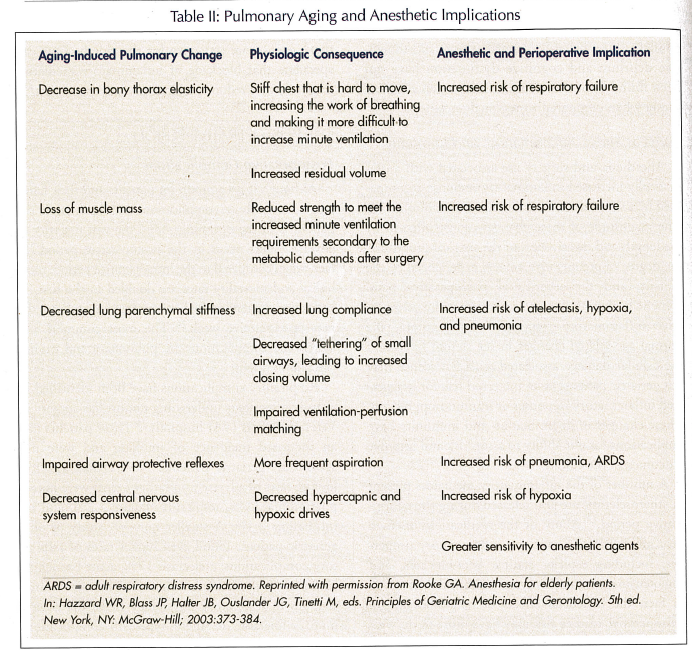

Respiratory complications have been identified in a study of patients undergoing noncardiac surgery in Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals.25 These patients had an increased incidence of smoking and were not specifically geriatric patients. Nevertheless, the following rates of adverse respiratory events were noted: pneumonia 3.6%, respiratory failure 3.2%, and re-intubation 2.4%. A smaller non–VA study of only geriatric patients found even higher rates of respiratory complications: atelectasis 17%, acute bronchitis 12%, and pneumonia 10%.26 The age-related changes in respiratory physiology make the elderly more vulnerable to these types of complications (Table II). In addition, pharyngeal and cough reflexes normally decrease with age, and these changes are exacerbated by anesthetics, muscle relaxants, pharyngeal surgery or instrumentation, neck surgery, and upper abdominal surgery.27-29 Although the intraoperative risk of aspiration and subsequent pneumonitis is small,30 these changes put the elderly at particular risk for aspiration postoperatively. Narcotic analgesics, which cause sedation and delayed gastric emptying, increase this risk.

The incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction is related to the underlying incidence and severity of coronary artery disease in the geriatric population. Elderly high-risk groups such as vascular surgery patients have rates of 4% for myocardial infarction and 9% for congestive heart failure,31 and the incidence of both events peaks on postoperative day 2. Mortality from perioperative infarction is high and averages approximately 30%. Many geriatric patients have coronary artery disease, and brief intraoperative ischemic events that respond well to treatment are not predictive of postoperative myocardial infarction. The etiology of postoperative infarction is more likely thrombosis, since surgery activates the coagulation cascade and impairs fibrinolysis.

The etiology of postoperative stroke is probably the same. Stroke is less common in the postoperative period than myocardial infarction is, but its incidence is far greater than would be expected in the absence of surgery.31 Although intraoperative hypotension is frequently cited as a cause, there is little evidence for this supposition. The vast majority of postoperative strokes occur after the patient recovers from anesthesia and has had an initially intact neurological examination. Elderly patients who have deliberate controlled hypotension during their anesthetics (a technique employed to minimize blood loss during surgery) do not have an increased incidence of stroke or postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Prolonged, profound hypotension, as occurs with cardiac arrest, causes global anoxic insults but not focal deficits. The presence of atrial fibrillation, artificial valves, or any other source of intracardiac clot or systemic embolism would therefore be more worrisome for the risk of stroke than an episode of hypotension. The tradeoff of risk between hemorrhage and embolism has resulted in the recommendation that anticoagulation therapy with warfarin should be stopped for only 4-5 days before surgery, and then restarted as soon as possible after surgery.

Analgesia

We know that inflammation and hypercoagulation peak after surgery, and this peak coincides with the postoperative period when most complications occur. It stands to reason, then, that good postoperative analgesia might decrease these responses and could possibly be linked to better outcomes. Good analgesia also provides better postoperative rehabilitation and functional status and may decrease the level and duration of assistance that a patient needs after surgery.

Regional anesthetics used for surgery can often be continued postoperatively as a means of providing analgesia. Although these techniques have high patient satisfaction, a well-conducted study done on general surgery patients found no advantage to postoperative regional analgesia with respect to cardiopulmonary outcomes, the stress response to surgery, or the subjective experience of pain.32 Unfortunately, very few studies have been conducted in isolated elderly populations, so these results may not be reflective of this group of patients.

Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) has greater safety, satisfaction, and outcomes than on-demand administration of pain medication or a fixed-dose regimen.33 However, patients with altered mental status or technology aversion may lack the ability to understand or effectively use PCA. Choosing an analgesic can be difficult because slowed drug metabolism, drug interactions, and drug side effects are all especially common in the elderly. Adjuncts such as cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors, ketorolac, clonidine, gabapentin, dexmedetomidine, and mixed agonist/antagonist narcotics all may have a role in decreasing the dosages and side effects of narcotic analgesics. This is important since the narcotic analgesics are the drug class that has been shown to have the most adverse drug events.34

The potential for adverse drug interaction is even higher in the elderly because they often take multiple medications for varying medical conditions. Adding new drugs complicates dosing regimens and can potentially increase the risk of overdose. A careful review of old and new medications should be done prior to discharge from the hospital. Primary care physicians or geriatricians can prompt this medication review and adjust medications as needed. These practitioners can also help to educate the patient’s family and other caretakers about the risks and warning signs of side effects and drug interactions.

Delirium and Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction

Despite the current and continuing rise in the number of elderly patients with complex medical illnesses who undergo surgery, there have generally been continuing improvements in surgical outcomes. The one major area of exception is that of postoperative cognitive impairment.35-38 Two types of impairment are seen: delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD). Delirium is more commonly seen in elderly patients, and POCD is a condition that is almost exclusive to the elderly. POCD can have a dramatic impact on a patient’s well-being, as abrupt declines in cognitive function can lead to a loss of independence, depression, withdrawal from society, and ultimately death.38

Delirium. The incidence of postoperative delirium varies from 5-10% for all age groups and 10-15% for those over age 70.36 Delirium is commonly characterized by fluctuating levels of consciousness, disturbed sleep/wake cycles, and altered psychomotor activity. Affected patients exhibit disordered cognitive function, thinking, perception, and memory. Although it is tempting to blame anesthetic drugs for the majority of cases of postoperative delirium, there has been no proven correlation between the two.13,14 In fact, there are numerous contributors to postoperative delirium, and they include advanced age, drug interactions, cerebral damage, surgery and anesthesia, hypoxia, sepsis, sensory deprivation or overload, electrolyte disturbances, pain, and endocrine or metabolic disorders. Other conditions such as depression, alcohol withdrawal, and substance abuse are also causes of delirium, but they may not be appreciated unless there is good communication between the primary caregivers and the surgical team. Fortunately, some causes of delirium are temporary and treatable; however, delirium still contributes to prolonged hospitalization and increased costs of medical care.

Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction is defined as “deterioration of intellectual function presenting as impaired memory or concentration.”37 This definition covers a very wide range of impairment from mild forgetfulness to severe cognitive dysfunction, resulting in loss of independence. The diagnosis of POCD often requires pre- and postsurgical neuropsychological testing, which is one reason why preoperative cognitive testing has been advocated in all elderly patients scheduled to undergo elective surgery. The diagnosis of POCD must include a new onset of decline in at least two areas of cognitive functioning persisting for at least two weeks after surgery.37 The causes of POCD remain unclear, but one plausible hypothesis is that of the “functional cliff.”38 This hypothesis postulates that normal aging causes a progressive decline in cognition so that, at some point, the patient is moving very close to a level that would be considered cognitive impairment or dementia. At this point, patients are very vulnerable to further insults, and the sudden onset of even mild trauma associated with surgery is enough to push them over the edge into a range of functioning that is considered impaired.

Surgical events that can play a role include systemic and cerebral microemboli, and this has been postulated as the most likely etiology for the neurocognitive dysfunction seen following coronary bypass procedures.35 Microemboli are also common after orthopedic procedures, and it stands to reason that this may be a cause of POCD following this type of surgery. Exposure to anesthetics may cause changes in the release of central neurotransmitters, and this could possibly lead to impaired memory. Geriatricians and other primary care providers could be instrumental in determining the types of dysfunction experienced and their impact on the individual, the family, and society at large. Future research is needed to identify the proper testing methods, appropriate criteria for diagnosis, and causes of the condition so that prevention and treatment can become a possibility.

Inflammation, Immunity, and the Stress Response

The body’s responses to both the physical and psychological stresses of surgery clearly influence inflammation and immunity. Improved attention to perioperative anxiolysis and analgesia may improve postoperative immune function. Once the stress response has been triggered, its pro-inflammatory effects can still be decreased by the use of beta- and alpha-blockers.15,16,20 Even more widespread perioperative use of beta-blockade is probably warranted. Other anti-inflammatory drugs like ACE inhibitors, statins, and COX-2 inhibitors should also be studied, and their use should probably be expanded.

The geriatric patient has even more difficulty with temperature regulation and maintenance of core body temperature under anesthesia than the general population of surgical patients. Even mild hypothermia is associated with lymphocyte suppression and increased stress hormone levels, and hypothermia can also increase the risk of postoperative wound infection and slow postoperative wound healing.39

The evidence also suggests that the perioperative effects on inflammation and immunity persist much longer than the traditional one month after surgery that has been designated and studied as the postoperative period. There is mounting evidence that the postoperative period may more realistically last for as long as 12 months. This has tremendous implications for long-term disease progression, morbidity, and mortality.

CONCLUSIONS

It is important to remember that the perioperative care of the elderly surgical patient needs to be much more comprehensive and multidisciplinary than has been appreciated in the past. The geriatric population is growing in numbers and complexity and will represent an increasingly large and diverse part of every physician’s practice. Unique to this population are physiological limitations and specific vulnerabilities that make a more comprehensive presurgical evaluation and plan necessary. While the same can be said for any population of patients, in the elderly it is even more important to remember that the patient isn’t all better when they go home from the hospital. Sometimes this is just the beginning of a period of long and progressive decline. New research into postoperative cognitive dysfunction and immunosuppression suggests reasons why the elderly may never appear to recover from surgery. However, this research also suggests many new areas of investigation that should be focused on the elderly in order to better determine their level of risk and help them return to at least their presurgical level of function.

The research reported in this article is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs.