Geriatric Medicine: A Clinical Imperative for an Aging Population, Part III

This is the third and final section of the policy statement. Part I appeared in the March issue and Part II appeared in the April issue of the Journal.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• The nation’s aging population is growing rapidly. The aging population is living longer, with fewer acute care based needs and more chronic care based needs. In general, our health care system meets chronic care needs in a limited and fragmented manner.

• Chronic care services are a hallmark of geriatric care. Geriatricians are physicians who are experts in caring for older persons; these primary care-oriented physicians are initially trained in family practice or internal medicine and complete at least one additional year of fellowship training in geriatrics.

• A subset of the nation’s elderly population requires geriatric care. Approximately 15% of community dwelling Medicare beneficiaries need access to a geriatrician or geriatric services provided by a primary care physician.

• The first category of non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries is comprised of seniors with multiple, complex chronic conditions. In addition, residents of nursing homes and other congregate care facilities need access to quality, geriatric care.

• Over the past ten years, peer reviewed literature has strongly supported geriatric care models. These innovative care delivery systems include the use of geriatric assessment, ongoing care coordination, a physician-directed multidisciplinary team and a holistic approach to patient care that involves clinical, psychosocial and environmental follow-up.

• Despite the benefits of geriatric care, a shortage in the geriatric work force persists. Today, there are approximately 7,600 certified geriatricians in the nation, despite an estimated need of approximately 20,000 geriatricians. The lack of geriatricians impedes the delivery of chronic care to needy, elderly individuals.

• Financial disincentives pose the largest barrier to entry into the field. Geriatricians are almost entirely dependent on Medicare revenues. Given their patient caseload, low Medicare reimbursement levels are a major reason for inadequate recruitment into geriatrics.

• The Medicare bill included several new chronic care provisions, including a largescale disease management pilot program. However, the new disease management program will not adequately address the needs of persons with multiple chronic conditions, nor will it address the financial disincentives within Medicare that have limited the supply of geriatricians.

• Different reforms are needed to increase interest in geriatrics, such as changes in the Medicare fee-for-service payment system, changes in the new disease management program, and changes in payment policy for federal training programs.

MEDICARE REFORM AND THE GERIATRIC PATIENT: HOW DOES DISEASE MANAGEMENT DIFFER FROM GERIATRIC CARE?

The Medicare program has recently undergone major reforms, such as the addition of outpatient prescription drug coverage and disease management. Will these new changes address the problems faced by frail older persons and the physicians who treat them?

Little is being done to change the nature of the system from acute episode care to sustained chronic care. The Medicare bill included several new chronic care provisions, including a new study on chronic care, a small scale physician-oriented demonstration program, and a larger scale disease management pilot program. However, as this section notes, the new disease management program may not adequately address the needs of persons with multiple chronic conditions.

The new disease management pilot program establishes chronic care improvement organizations (CCIOs) under the Medicare fee-for-service program. CCIOs, which may include disease management organizations, health insurers and integrated delivery systems, will be required to improve clinical quality and beneficiary satisfaction and achieve spending targets in Medicare for beneficiaries with certain chronic conditions. CCIOs will be held at full risk for their role in helping beneficiaries manage health through decision-support tools and the development of a clinical database to track beneficiary health.

Why aren’t disease management programs sufficient to transform the system of care for frail older persons?

Disease management covers many different activities influencing individual health status and the use of health care services. Typically, disease management programs treat patients with specific, clearly defined diseases, such as diabetes, asthma, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease where the evidence is clear and management strategies are straightforward. Disease management focuses on patient education and evidence-based self-management strategies as tools to improve care. Disease management relies on improved disease outcomes to improve health and reduce disease-specific health care utilization. Patients who are the best candidates for disease management programs are those who have the motivation and cognitive skills to appreciate their role in illness management and implement self-management strategies.

Geriatric care is another term for coordinated care or care management. Care coordination programs generally enroll patients with multiple chronic conditions. The combination of conditions puts the patients at high risk of medical and social complications that requires specific interventions tailored to the specific needs of each enrollee. These interventions include an array of services, such as telephone coordination with other physicians, extensive family caregiver support, referrals for social supports, and high levels of medication management.

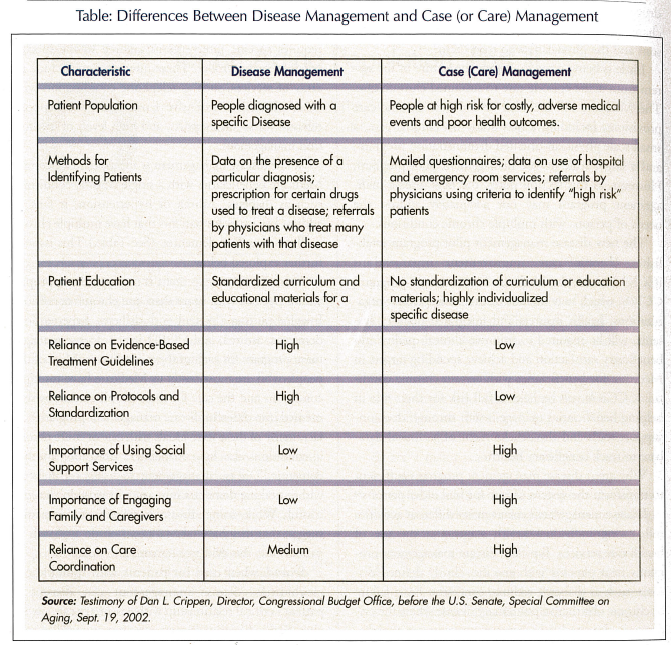

While disease management is appropriate for certain Medicare beneficiaries with a single chronic condition, such as diabetes, asthma or hypertension, it fails to address key issues for patients that have multiple chronic illnesses and/or dementia. (See Table.) This issue is further explored below.

First, disease management is not typically appropriate for persons with more than one chronic condition. Imagine putting a patient with diabetes, hypertension, dementia, asthma, and COPD into a disease management program for each of these conditions. Most of the people who are most costly to Medicare have multiple conditions and the care for these people cannot be segmented into different disease management programs. In fact, many of these individuals with one or more chronic conditions also have Alzheimer’s disease or another dementia. Disease management focusing on diabetes without taking dementia into account wouldn’t be successful. While some disease management companies suggest that they have taken a new holistic approach to patient care, this evidence remains anecdotal.

Second, when used for patients with multiple co-morbidities, disease management can disrupt a patient’s critical relationship with a primary care physician. Some disease management programs utilize specialists that focus only on specific interventions tailored to one condition. The nature of chronic illness requires a comprehensive, care coordination-based approach that utilizes a variety of interventions. Disease management programs that lack a physician component do little to coordinate the care of older persons with multiple illnesses and little to mitigate the safety hazards of fragmented, redundant care delivered by multiple providers.

Third, a major component of disease management involves self-management and patient education. These simply do not work for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia. Diabetes self-management often involves patient education, or patient self-management, which is inappropriate for a beneficiary with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia. Likewise, disease management for asthma and hypertension depends on patient compliance with treatment recommendations; this would not be effective for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementia. In comparison, care coordination models rely on engaging family and caregivers and maximizing their involvement.

Fourth, disease management does not always address functional issues that are common in old age or the complications that arise from multiple chronic illnesses.

Fifth, treatment guidelines provide little guidance when multiple chronic illnesses co-exist. Therapeutic decisions are less straightforward, making treatment decisions less amenable to algorithmic self-management protocols.

Finally, disease management programs place little importance on using social support services, a major component of a care coordination approach, which relies on a holistic model of patient care.

Additional physician participation and attention to the needs of multiple chronic conditions and especially dementia could improve project outcomes, but the model remains different from the approach of a new fee-for-service care coordination benefit.

The final section of this report suggests steps that could be taken to address the limitations in the new disease management program as well as in the health care system in general.

SOLUTIONS

As the IOM and other organizations have noted over the past three decades, the nation will benefit from an increased supply of geriatricians. In addition to certified geriatricians, there is a need for increased geriatric training and awareness in other physician specialties and other health professions. To achieve these goals, policy makers should consider the following recommendations to create an appropriate market and incentives to generate more appropriately trained professionals:

1. Traditional Medicare Payments: As stated above, limitations in Medicare fee-for-service payments present a major barrier into entering geriatrics and providing high quality care to patients. Congress could make two changes to address this issue. First, Medicare should cover geriatric assessment and care coordination services. Second, Medicare should develop and implement a risk adjuster to account for the time and complexity involved with treating a frail elderly patient where a physician’s practice has a high number of these patients. Revamping the fee schedule may help attract physicians and other appropriate non-physician professionals to a career in geriatrics.

2. Medical Education Loan Forgiveness: Data on the number of course offerings in geriatrics suggest that medical students are unaware of geriatrics and lack adequate incentives to enter the field. Furthermore, physicians who have an interest in pursuing geriatric fellowships are often discouraged because of their large education debt and the relatively low compensation after training. The Public Health Service and/or the National Institutes of Health could provide loan forgiveness to individuals who get a CAQ in geriatrics. This strategy has been used in other work force shortage areas in the past.

3. Graduate Medical Education Changes: Medicare graduate medical education (GME) is the primary financing system for physician training programs. In the past, Congress has used the GME program to create incentives to train increased numbers of geriatricians. Under the current law, hospitals receive limited Medicare GME funds for physician trainees. The 1997 Balanced Budget Act instituted a per-hospital overall cap on the number of GME slots that will be supported by the Medicare program. Policy makers should provide for further limited changes in this area by authorizing a limited waiver in the per hospital cap for geriatric trainees.

4. Provide adequate funding for Title VII geriatrics programs: Title VII of the Public Health Service Act provides three types of geriatric health professions programs: geriatric academic development awards, geriatric education centers, and awards to geriatric training programs. These programs address shortages in academic geriatrics. In recent years, Congress has increased funding for this program. Congress should continue these important increases.

5. Maintain and expand the Title VII programs: The geriatric health professions programs are up for Congressional reauthorization this year. The geriatric health professions programs have received tremendous commendations from current recipients for their efforts to increase the number of junior faculty in geriatrics and help multi-disciplinary geriatrics training programs grow. Congress should increase the authorization levels and expand these programs in other ways.

6. Institute Incentives for Medical Schools, as well as professional schools, to incorporate geriatrics into training programs: As stated earlier in the report, many medical schools do not offer appropriate levels of geriatrics-focused curriculum, despite efforts by the Association of American Medical Colleges and others to increase geriatrics’ curriculum. All health care professional schools, at all levels, should be incentivized to incorporate and highlight geriatrics into their curriculum.

7. Medicare Chronic Illness Care Programs: Under the new CCIO program, part of what could make one who is submitting a proposal successful is demonstrating that their care management team and staff have undergone some level of geriatric-specific training as it relates to the progression of disease for those conditions which the vendor proposes to manage. In addition, CMS could require each bidder to demonstrate a certain percentage of physician involvement in their CCIO. Another smaller demonstration authorizes a physician-based pay for performance model. Congress should further explore the value of the pay for performance model in improving patient care and adequately reimbursing physicians for information technology and other related care management expenses.

8. Medicare and/or Medicaid Certified Nursing Homes: Many geriatricians serve as nursing home medical directors. However, due to limited supply, some nursing home medical directors lack geriatrics training. As the primary payors for nursing home care, Medicare and Medicaid could use their purchasing power to create change over time. CMS could modify conditions of participation so that a certain percentage of staff would have to have completed some type of geriatric training. The industry would be provided time to comply with new training requirements.

CONCLUSION

It is a policy imperative to facilitate development of a health care workforce that can address the needs of a growing elderly population. The demographics and concomitant concern over financing Medicare in the future makes the need for action a top priority. Movement toward change will take steady and long-term leadership that has to begin now. It will take a focused effort from policy makers to see that proper incentives are in place for geriatric care providers. These incentives must be sufficient to meet current and expected need.

Acknowledgments

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) acknowledges those who assisted in the preparation of this report. We thank Ms. Jane Horvath, an independent consultant in health care policy and Ms. Susan Emmer, long-time AGS policy consultant, for their assistance in drafting the report. Several former and current AGS and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs (ADGAP) Board members reviewed and commented on the report. They include AGS executive committee members: Drs. Richard Besdine, Paul Katz, David Reuben, Meghan Gerety, and Jerry C. Johnson, and ADGAP Board member Dr. John Burton. In addition, Dr. Gregg Warshaw, past AGS and ADGAP President, and Dr. Elizabeth Bragg, co-investigator of the ADGAP Longitudinal Study of Training and Practice in Geriatric Medicine, contributed to this report.

The American Geriatrics Society is a nationwide, not-for-profit association of geriatric health care professionals dedicated to improving the health, independence, and quality of life for all older people. The AGS promotes high quality, comprehensive, and accessible care for America’s older population, including those who are chronically ill and disabled. The organization provides leadership to health care professionals, policy makers, and the public by developing, implementing, and advocating programs in patient care, research, professional and public education, and public policy.

The Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs was formed in the early 1990s to provide a forum for academic geriatric medicine divisions and program directors. Its purpose is to foster the enhancement of patient care, research, and teaching programs in geriatrics medicine within medical schools and their associated clinical programs. ADGAP is affiliated with the American Geriatrics Society in New York City and shares offices and staff with the AGS. The Empire State Building, 350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 801, New York, New York 10118, (212) 308-1414, www.americangeriatrics.org