Improving Transition and Communication Between Acute Care and Long-Term Care: A System for Better Continuity of Care

Transition of nursing home residents to and from the hospital can be problematic. A medical university hospital, together with area nursing homes, identified administrative and communication issues hindering efficient transfers. Cooperative solutions were developed and systems implemented to improve communication and provide smoother continuity of care. Challenges to communication between a teaching hospital and a nursing home arise from many factors, including differing cultures in the two environments, the hospital’s numerous medical teams, its monthly rotation, and the nursing home’s frequent turnover of administrative and nursing staff. While many conditions are beyond control, development of standardized forms, targeted education, and constant monitoring have successfully reduced the number of problems between hospital and nursing home, and fostered recognition that, although the tasks and cultures differ, the two should be united in an effort to provide optimal care.

BACKGROUND

In the continuum of care, the point of transfer is a particularly crucial one.1-4 For residents of nursing homes, the change is marked by a change of status: they immediately become “patient” when entering the hospital, resuming “resident” status upon discharge. As in any effective transfer, the elements of designated coordinator, enhanced communication, standardized process, and patient assessment are crucial.5-7 Effective transfer is not automatic;8-10 a workable system to manage these transitions has been called for in Malone and Danto-Nocton’s appeal for standardized “forms or checklists.”11

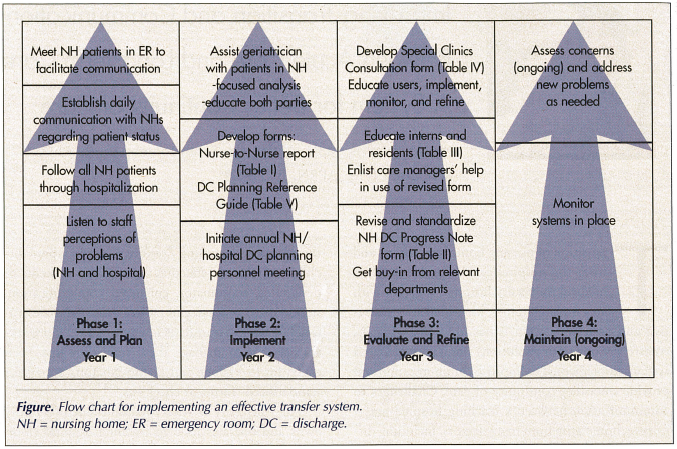

The University of Texas Medical Branch (UTMB) owns and operates its own teaching hospital (John Sealy Hospital), which admits and refers patients to ten nursing homes and two long-term acute care hospitals (LTACs) in the county. Some hospital faculty physicians have admitting privileges in six of these nursing homes. These nursing homes have a total of 758 beds, all dually certified, except for 20 beds in an Alzheimer’s unit. Most of the activity described in this article involved six nursing homes. Using observation, input from all parties, and refinement, we developed a system for transferring patients between a medical university hospital and area nursing homes that provides smoother continuum of care between facilities.12 While the challenges of communication between a teaching hospital and a nursing home are real, we have successfully reduced the number of problems that occur. The first step in institutional change, buy-in at the administrative level,13 was observed by the medical director of the Geriatric Service Line and the director of Geriatric Services in creating the role of nursing home liaison (NHL). This advanced practice nurse position, which reports to the director of Geriatric Services, has no known precedent and was charged first with addressing the longstanding nursing home complaint of poor communication. Nursing homes requested that the hospital designate one person with whom they could communicate their concerns about hospitalized residents. The process is summarized in the Figure.

PROBLEMS, SOLUTIONS, AND SYSTEMS

Problem from the Nursing Home Perspective

Assessment of the problem started by visiting different nursing homes (NHs) to meet with administrative staff. Separately, NH personnel voiced the common themes of faulty communication: they could not read the doctor’s handwriting in discharge orders, there was no telephone number to call for clarification, and calls to the hospital’s main number proved fruitless. Additionally, care managers (CMs) did not send appropriate papers when patients were discharged, and nurses did not give thorough reports. Frequently missing were results from the last blood sugar test and the time of last insulin administration. Nursing home personnel were not updated about residents’ progress in the hospital, finding out about a death only when a family arrived at the facility to retrieve a resident’s belongings.

Specific departments were cited. Nursing homes had difficulty making clinic appointments, they could not convey residents’ special needs to clinic personnel, and they usually received no documentation after a clinic visit. Sometimes patients were sent to the emergency room (ER) but not admitted, and returned without a discharge report or even notification, sometimes just showing up in a taxi. However, the ER, without checking further, was quick to report nursing homes to the state for abuse or neglect. (ER issues will be addressed in a future article.)

Problems arose from differences in culture. Late discharge of patients did not give nursing homes time to obtain medications or equipment, which takes about four hours to be delivered by suppliers. Nursing homes do not order equipment before a patient arrives because last-minute changes to discharge plans can leave them financially burdened with expensive medications. Acute care physicians usually do not know that “under the prospective payment system (PPS), skilled nursing facilities have a financial incentive to fully understand the patient’s care needs prior to acceptance or transfer.”14 Nursing homes do a cost analysis before accepting patients taking expensive medications such as intravenous (IV) antibiotics. Acute care physicians are often unaware of the problem that IV administration can pose since some nursing home–licensed staff may not be certified to administer IV medications. Lastly, nursing homes wanted hospital CMs to consider agencies with which they had contracts when discussing hospice agencies with residents’ families.

Problem from the Hospital Perspective

Not surprisingly, hospital staff had their complaints about nursing homes. Nursing staff complained that often when calling nursing homes to give a report or inquire about a patient’s baseline mental status or prior level of activity, no one answered the telephone, the person answering did not know the information, or they were put on hold indefinitely. Case managers complained of not receiving timely answers to their inquiries for nursing home placement, although pages of medical documentation were sent. And when patients who did not need ambulance transportation were ready for discharge, nursing homes did not pick them up, especially at night.

Following Patients through Hospital Stay

In the first year of analysis, the nursing home liaison followed all nursing home patients admitted to the hospital. The liaison immediately began daily communication of patients’ progress and deaths. The liaison saw missing medical information at discharge, followed by requests from medical care providers without hospital privileges. As a result, the liaison spent hours in medical records, retrieving information that should have been sent at discharge. If nursing homes called when their patients were on the way to the ER, the liaison would meet the patient there. Most nursing home patients are admitted to the ER with altered mental status, and since many may have baseline dementia, they need more than anything to “feel safe and secure while not overloading them with too many details or questions.”15 The liaison also provided emotional support to stressed spouses and relatives accompanying the patient, facilitating communication between nursing home staff, family members, and ER staff.

Following Patients through the Nursing Home

Late in year two, the liaison began attending three nursing homes three days per week, following one geriatrician’s patients closely. Complaints previously voiced by the nursing homes became very real. Medical terms on fax transmittals of hospital documentation, perhaps decipherable by a physician or advanced practice nurse, were unreadable to most nursing home care providers. Clarifying orders could be frustratingly impossible. If one called the hospital’s main number, the operator no longer had the patient’s name because names are removed from the computer list upon discharge. If one called the hospital nursing unit (assuming one knew which unit to call), the nurse answering in the next shift might not know the patient or the discharging physician. By the time of the call, the chart might be on its way to medical records; medical records personnel cannot discuss patients’ cases. In addition to experiencing these problems firsthand, the liaison observed nursing home systems and practices, developing a closer working relationship with the nursing and rehabilitation staff. Attending weekly interdisciplinary rehabilitation meetings gave a better picture of the skilled nursing patients, enabled the liaison to better understand and explain practice patterns of nursing home and hospital caregivers. The liaison began to educate both parties in each other’s systems and the rationale for each.

Solutions Implemented and Refined

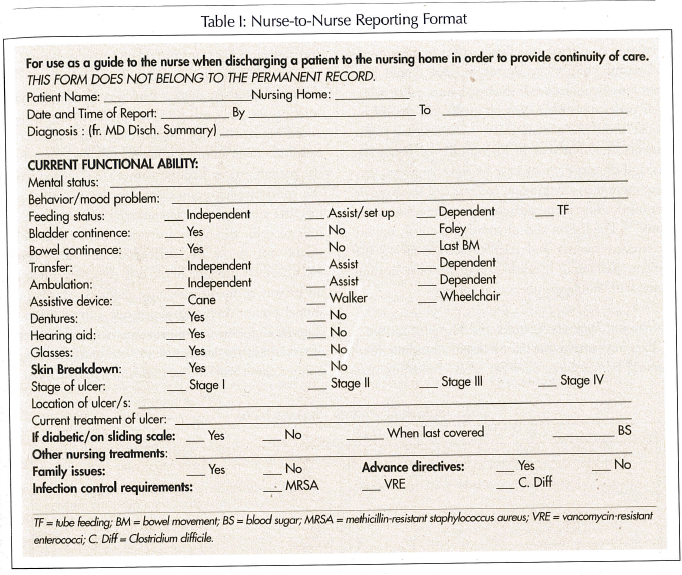

After evaluating all problems stated or observed, we began implementing improved systems, including form development and continuing education of nursing home and hospital personnel. For better reporting from hospital nurse to nursing home nurse, an orange form was developed (Table I). This form was placed in all nursing home patients’ hospital charts, and reminded the bedside nurse of what needed to be reported to the nursing home upon discharge. A copy of this form was also shared with the nursing homes so the NH nurse could proactively ask questions during hospital reports. This form also reminded the hospital nurse to give complete but expedited reporting. The liaison provided ongoing informal education on use of this form.

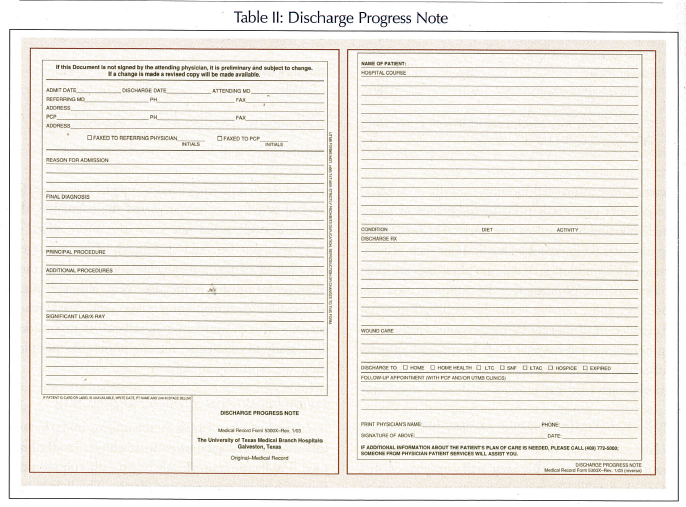

In reviewing problems with discharge summaries, we found that nearly every medical and surgical specialty service had a different discharge Progress Note form. We consolidated these into one form for use by all hospital services’ patient discharges to nursing homes (Table II). The NHL implemented this revision by talking to division business managers and unit nurse managers, and by keeping units stocked with copies of the newly revised form. The liaison enlisted care managers to help educate discharging physicians during their daily rounds with the medical teams. Nursing staff in-service education in units with nursing home patients was begun, but it became apparent that individual education for a captive audience—the intern or resident writing the orders—was more effective. There is a very important requirement in the revised Discharge Progress Note that the discharging physicians must print their names and provide their telephone numbers.

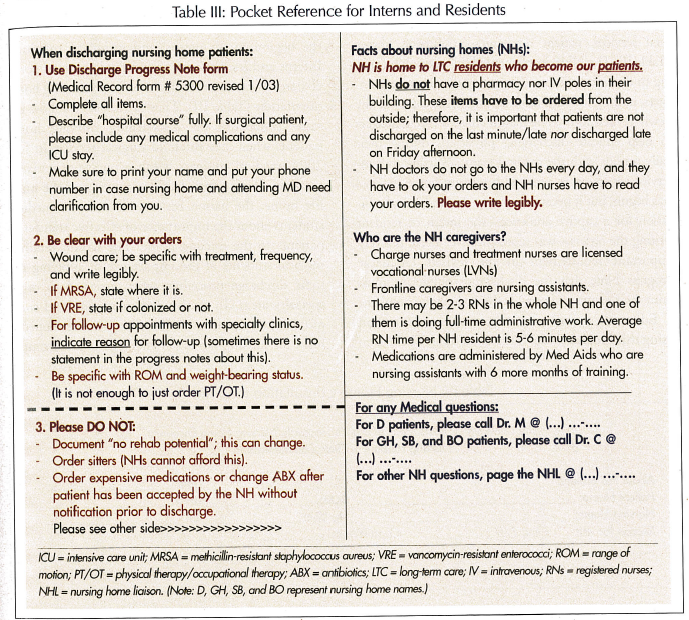

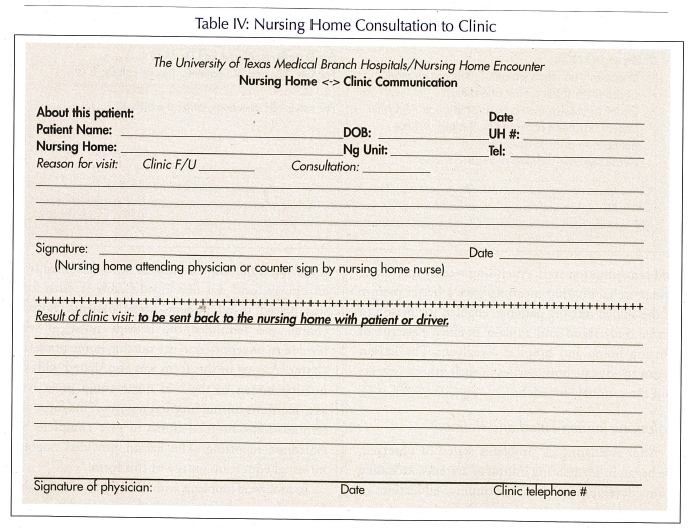

Educating overstressed interns and residents16 on using this Progress Note form is ongoing. The liaison participates in monthly interdisciplinary team orientation in the acute care for the elderly (ACE) unit at the beginning of interns’ and residents’ rotations. Interns and residents are provided a laminated pocket-sized “cheat sheet” with the basics of nursing home orientation (Table III). They are asked to follow the same procedure for discharging nursing home patients when they rotate to surgical service. In July 2004, medical students began a one-week geriatric rotation. During their half-day rotation in the nursing home, the liaison educates fourth-year medical students about the importance of effective transfer of patients to the nursing home. The liaison reminds medical students of the importance of applying the same discharge procedure when assigned to other specialty areas. To resolve documentation and communication problems in the clinic, we developed a form for nursing home patients’ charts to accompany them to their clinic visits, and to be returned with documentation as to what transpired (Table IV).

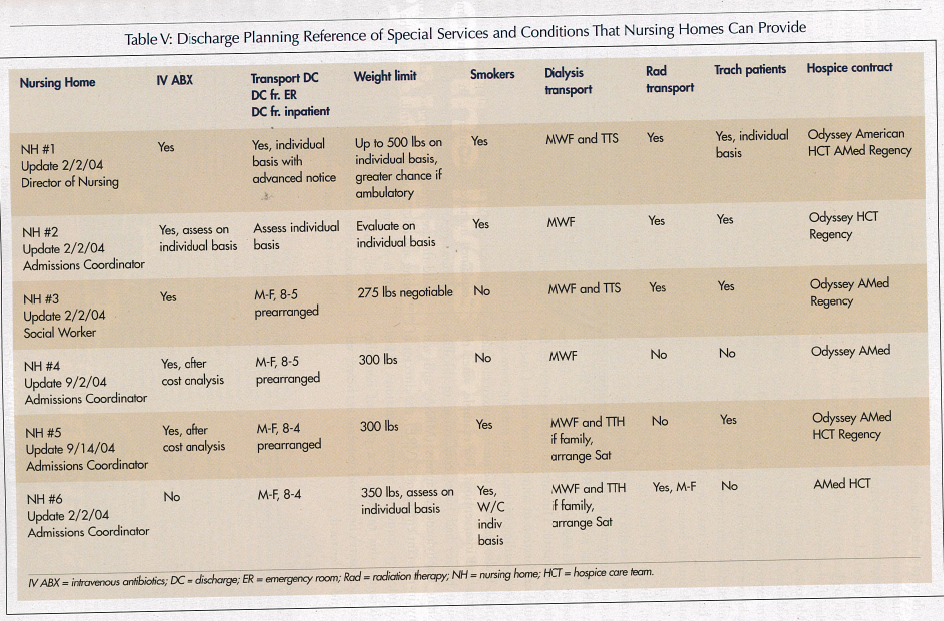

We asked nursing homes to list hospice agencies with which they had a contract, and to develop a list to assist CMs in placement (Table V). Because certain conditions delayed whether nursing homes would accept a patient, CMs found this information invaluable. Care managers could advise families whether a certain service requirement existed at a desired nursing home. When no nursing homes can provide complex care, care managers refer families to long-term acute care hospitals.

Early in year two, we implemented a program of annual nursing home meetings. A luncheon hosted by Geriatric Services for nursing home administrators, directors of nursing (DONs), and admissions coordinators is also attended by key hospital personnel: care management supervisors, ER nursing director, ER social worker, ER clinical nurse specialist, director of Geriatric Services, and senior helpline nurse coordinator. This annual meeting provides for mutual exploration of solutions and mutual insights into corresponding systems in the nursing home and hospital. It also serves as a venue for introducing new concerns and interventions. For example, when the nursing homes had issues concerning methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), the director of Epidemiology came to answer questions. Most importantly, this meeting is a place of neutrality where each party’s needs and concerns are heard, valued, and understood.

For their part, nursing homes have addressed problems with their systems. Recognizing that some fax transmittals may get mixed up with other documents and delay response to case manager inquiries, they decided to place a dedicated fax machine for inquiries in the admissions coordinator’s office. Two nursing homes also moved to provide more training for new admissions coordinators. Two other nursing homes have recently sent their admissions nurses to evaluate patients referred by hospital care managers. These experienced nurses, usually admissions coordinators or MDS [Minimum Data Set] nurses, work with their DONs to decide whether to accept or reject a referral. This initial referral reduces the potential for misplacement, assuring that all parties share assumptions about level of care, payment, etc.17

CONCLUSION

Through cooperation, our process of improved communication evolved, but it was not without problems. At times, cooperation from hospital personnel occurred only after the nursing home liaison explained management’s interest. In nursing homes, solutions generally worked, but a change in DON could threaten procedures in place. Constant monitoring and education are essential. Crucial to the system is our annual meeting with nursing home personnel, which reinforces the notion that, although our tasks differ, we are unified in our goal: to provide the best care to our patients.