Geriatric Medicine: A Clinical Imperative for an Aging Population, Part II

This is the second section of the policy statement. Part I appeared in the March issue of the Journal. The final section will appear in the May issue.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• The nation’s aging population is growing rapidly. The aging population is living longer, with fewer acute care based needs and more chronic care based needs. In general, our health care system meets chronic care needs in a limited and fragmented manner.

• Chronic care services are a hallmark of geriatric care. Geriatricians are physicians who are experts in caring for older persons; these primary care-oriented physicians are initially trained in family practice or internal medicine and complete at least one additional year of fellowship training in geriatrics.

• A subset of the nation’s elderly population requires geriatric care. Approximately 15% of community dwelling Medicare beneficiaries need access to a geriatrician or geriatric services provided by a primary care physician.

• The first category of non-institutionalized Medicare beneficiaries is comprised of seniors with multiple, complex chronic conditions. In addition, residents of nursing homes and other congregate care facilities need access to quality, geriatric care.

• Over the past ten years, peer reviewed literature has strongly supported geriatric care models. These innovative care delivery systems include the use of geriatric assessment, ongoing care coordination, a physician-directed multidisciplinary team and a holistic approach to patient care that involves clinical, psychosocial and environmental follow-up.

• Despite the benefits of geriatric care, a shortage in the geriatric work force persists. Today, there are approximately 7,600 certified geriatricians in the nation, despite an estimated need of approximately 20,000 geriatricians. The lack of geriatricians impedes the delivery of chronic care to needy, elderly individuals.

• Financial disincentives pose the largest barrier to entry into the field. Geriatricians are almost entirely dependent on Medicare revenues. Given their patient caseload, low Medicare reimbursement levels are a major reason for inadequate recruitment into geriatrics.

• The Medicare bill included several new chronic care provisions, including a largescale disease management pilot program. However, the new disease management program will not adequately address the needs of persons with multiple chronic conditions, nor will it address the financial disincentives within Medicare that have limited the supply of geriatricians.

• Different reforms are needed to increase interest in geriatrics, such as changes in the Medicare fee-for-service payment system, changes in the new disease management program, and changes in payment policy for federal training programs.

THE GERIATRIC TRAINING GAP—IS THERE A SHORTAGE?

Today, there are approximately 7,600 certified geriatricians in the nation.1 While estimates of potential needs for geriatricians vary, most experts agree that our nation faces a severe and worsening geriatric shortage, both in the area of clinical and academic geriatrics.

The Alliance for Aging Research estimated that another 14,000 geriatricians are currently needed to adequately care for the elderly population.2 By 2030, they estimate the need to have 36,000 trained geriatricians.2 A 1987 IOM study estimated the need for clinical geriatricians in 2000 to range from 9,000 to 29,000 depending on the mode of geriatric practice and other factors involving the quality of care delivered.3 Based on both of these assumptions, the United States lags far behind in training an adequate supply of clinical geriatricians to care for the nation’s frail elderly.

The supply of academic geriatricians is also insufficient. There are approximately 900 full time equivalent (FTE) academic geriatricians working in U.S. medical schools.4 The Alliance for Aging Research estimates that 2,400 geriatric academicians are needed to perform various functions, such as integrating geriatrics into other specialties and across other health care settings, training new geriatric fellows, and translating new research into means of caring for older persons. Other studies had similar findings.3 An IOM advisory panel recommended that at least nine academics trained in geriatrics sit in each medical school, but only 30 percent of medical schools have reached this target.5

As adequate numbers of geriatricians do not exist nationwide, geriatric faculty are needed to train other primary care and specialist physicians in the geriatric model of care. In this regard, program directors in family practice and internal medicine predict that 2,000 geriatric faculty are needed to train all medical residents, not just those in geriatric residency programs, in geriatric care principles.6 A recent study suggests that shortages of geriatrics faculty in internal medicine and family practice residency programs still exist.7

While the number of physicians certified in geriatrics has increased over the past ten years, rates of growth are far behind projected need, due to inadequate numbers of individuals entering geriatrics and inadequate rates of recertification in geriatrics.

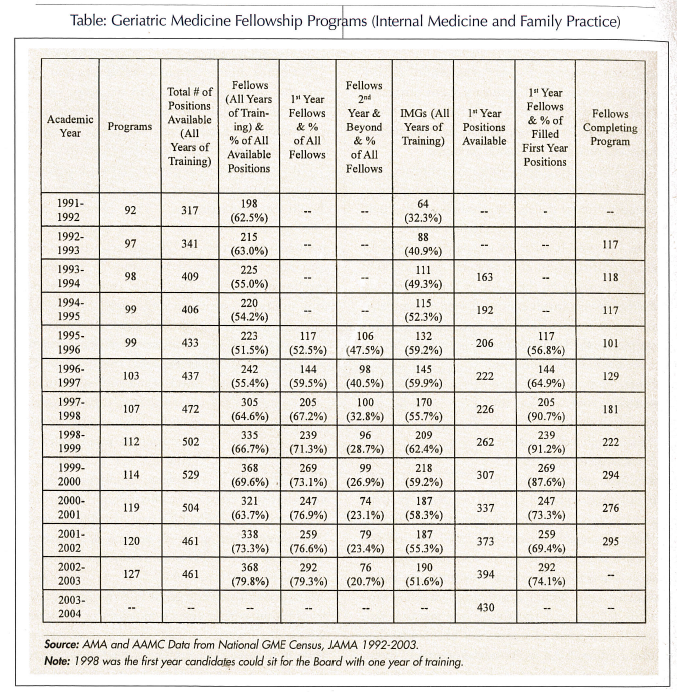

Given the number of geriatric fellowship slots in training programs, over 350 new geriatricians should enter practice each year. However, since 1999 geriatric fellowship training programs have graduated an average of 270 new geriatricians each year, and they operated at about 75 percent of enrollment capacity.8 (See Table regarding fellowship positions since academic year 1991-1992.) Furthermore, recertification rates average 50 percent; this is expected to decrease the total number of geriatricians over the next decade, despite growth in the number of geriatric training programs.1,8 As geriatrics is a relatively new specialty, some geriatricians were initially certified without prior fellowship experience; these individuals have failed to recertify. This is contributing to an expected 27 percent decrease in the number of currently certified geriatricians from 1998 to 2004.9

The geriatric training gap is incongruous with the needs of our rapidly aging population or the reality of how all physicians actually spend their office time while in practice. The degree to which there is geriatrics training in physician specialties varies considerably. While just over 90 percent of all internal medicine residency programs include some geriatric curriculum, only 40 percent require geriatric medicine clinical training exceeding 25 half-days and about one-third of these programs require fewer than twelve half-days.7 Fifty five percent of family practice programs require more than 25 half-days; nevertheless, 15 percent require less than six days of geriatrics training.7 Of the many specialty and sub-specialty postgraduate training programs, only 27 of 91 non-pediatric programs, have any specific curriculum training requirements in geriatrics.10 About 14,000 physicians in specialties other than family practice and internal medicine are certified each year, most of whom will have received no post-graduate experience in geriatric medicine as it relates to their field.10

The training gap is striking when considered in the context of the aging population. Office visits by geriatric patients comprise about 40 percent of the average internists’ practice and about one quarter of all visits to family physicians.10

Data suggests that inadequate numbers of physicians are entering the geriatrics field. Additionally, non-geriatricians lack adequate training in geriatric principles. This is startling, considering the increasing longevity of Americans and prevalence of chronic conditions. The next section explores reasons for the work force shortage in geriatrics.

REASONS FOR THE GERIATRICIAN SHORTAGE

While interest in entering the field of geriatrics is slowly increasing, the number of geriatricians remains low and some training positions remain unfilled. In short, there remains a geriatric training gap. Despite the small but growing numbers of physicians selecting geriatrics as a career, practicing geriatricians reported unusually high job satisfaction in a recent study, even though satisfaction is marked by the physicians practice environment and income, both of which have negatively influenced trainee desire to enter geriatrics.11

If there is a well-documented need for geriatricians and the job is satisfying, why aren’t more physicians going into geriatrics?

The answer to this question is multi-faceted. Physician interest in a specialty or sub-specialty depends on various factors, such as patient demands for service, anticipated revenues, specialty interest developed through exposure during medical school, and preferences for where to train and to work.12 In the case of geriatrics (despite the job satisfaction noted above), financial disincentives, which exacerbate large medical debt responsibilities, pose the largest barrier to entry into the field.

Geriatricians are almost entirely dependent on Medicare revenues, given their patient caseload. The IOM and MedPAC identified low Medicare reimbursement levels as a major reason for inadequate recruitment into geriatrics.6,13 Geriatricians are financially disadvantaged relative to other physicians in the health care system, making geriatrics less attractive. The financial bias in the system favoring specialists and sub-specialists over primary care physicians is well recognized. Because of the complexity of care needed and the time required to deliver quality care, Medicare payment policies currently provides a disincentive for physicians to enter the field of geriatrics and to carry a full caseload of Medicare beneficiaries who are frail and chronically ill.

First, the physician payment system does not cover the cornerstone of geriatric care—assessments and the coordination and management of care—except in limited circumstances. Care management includes services such as telephone consultations with family members, medication management, and patient self-management services. Geriatricians spend considerably more time performing care management services than other providers.

Second, the Medicare physician reimbursement system bases payment levels on the time and effort required to see an “average” patient, and assumes that a physician’s caseload will average out with patients who require longer to be seen and patients who require shorter times to be seen over a given time period. However, the caseload of a geriatrician will not “average” out. Geriatricians specialize in the care of frail, chronically ill older patients; the average age of the patient caseload is often over age 80.

Inadequate reimbursement ignores an important factor in treating medically complex and/or chronically ill patients; caring for these patients is fundamentally different than caring for the typical Medicare patient. All aspects of evaluation and management of patients are made more time consuming and difficult by these differences. History taking is more time consuming because of sensory, communication, and cognitive impairments and the frequent need to obtain additional information from sources beyond the patient. Physicals are more time consuming because of mobility restrictions. Supplemental exams are required to care for the frail elderly including initial and subsequent assessments of hearing, vision, and mental status. Medical decision-making is more complex and more time consuming because of the interaction of multiple chronic illnesses and multiple medications. Care coordination needs are greater because the care must typically be coordinated with not only the patient but also caregivers. Indeed, many activities require significant non-face-to-face time—meaning pre- and post-service time outside of the office visit. Until these factors are acknowledged by the fee schedule, geriatric practices will not flourish nor will the geriatrician shortage end.

Third, certain practice settings where geriatricians typically work may appear unattractive to trainees. For instance, many geriatricians spend all or part of their practice in a nursing home setting. This environment, with increased and typically not reimbursed telephone responsibilities, increasingly high malpractice premiums, complex patients with multiple co-morbidities, and historically low reimbursement, fails to attract many practicing physicians.

The limitations in Medicare reimbursement strongly influence geriatrician supply. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a sizable number of geriatricians cannot maintain a private practice without some level of subsidization to help sustain the practice, ranging from seeing non-Medicare patients to nursing home medical director responsibilities or other mechanisms. Clearly, until the reimbursement challenges are resolved, many trainees will not seek out geriatrics as a career option.

Acknowledgments

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) acknowledges those who assisted in the preparation of this report. We thank Ms. Jane Horvath, an independent consultant in health care policy, and Ms. Susan Emmer, long-time AGS policy consultant, for their assistance in drafting the report. Several former and current AGS and Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs (ADGAP) Board members reviewed and commented on the report. They include AGS executive committee members: Drs. Richard Besdine, Paul Katz, David Reuben, Meghan Gerety, and Jerry C. Johnson, and ADGAP Board member Dr. John Burton. In addition, Dr. Gregg Warshaw, past AGS and ADGAP President, and Dr. Elizabeth Bragg, co-investigator of the ADGAP Longitudinal Study of Training and Practice in Geriatric Medicine, contributed to this report.

The American Geriatrics Society is a nationwide, not-for-profit association of geriatric health care professionals dedicated to improving the health, independence, and quality of life for all older people. The AGS promotes high quality, comprehensive, and accessible care for America’s older population, including those who are chronically ill and disabled. The organization provides leadership to health care professionals, policy makers, and the public by developing, implementing, and advocating programs in patient care, research, professional and public education, and public policy.

The Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs was formed in the early 1990s to provide a forum for academic geriatric medicine divisions and program directors. Its purpose is to foster the enhancement of patient care, research, and teaching programs in geriatrics medicine within medical schools and their associated clinical programs. ADGAP is affiliated with the American Geriatrics Society in New York City and shares offices and staff with the AGS.

The Empire State Building, 350 Fifth Avenue, Suite 801, New York, New York 10118, (212) 308-1414; www.americangeriatrics.org.