Caregiver Depression

BACKGROUND

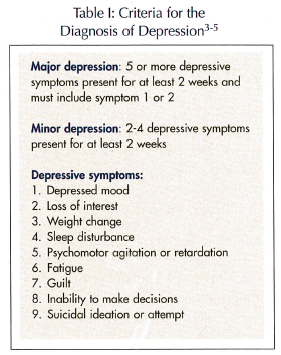

Despite the extensive literature on informal caregiving, an important source of personal care services in the United States,1 there is no consistent definition of a caregiver or caregiver depression. In this article, unless otherwise mentioned, a caregiver is broadly defined as one who provides informal care—including basic activities of daily living (ADLs), such as bathing and dressing, or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as cooking and housework—to a family member or friend. Depression is defined either according to research and screening tools such as the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale (CES-D)2 or preferably the use of a mental status examination to identify criteria set forth by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition-text revision, as shown in Table I.3-5 The authors focus on depression in caregivers over age 50, since this group will play an increasingly important role as the population ages.

Caregivers provide a significant amount of informal care to older adults with chronic diseases and disabilities in the community. According to a recent report, over 90% of Medicare enrollees aged 65 or older requiring personal care receive informal care for chronic disabilities.6 A 2004 survey of caregivers revealed that over 70% of all informal caregivers care for someone over age 50. In addition, older caregivers are more likely to care for older care recipients. Older care recipients often suffer from chronic diseases.1

Caregivers provide a significant amount of informal care to older adults with chronic diseases and disabilities in the community. According to a recent report, over 90% of Medicare enrollees aged 65 or older requiring personal care receive informal care for chronic disabilities.6 A 2004 survey of caregivers revealed that over 70% of all informal caregivers care for someone over age 50. In addition, older caregivers are more likely to care for older care recipients. Older care recipients often suffer from chronic diseases.1

The care provided by informal caregivers has substantial economic value. Arno7 argues that the estimated national value of informal caregiving provided by all U.S. caregivers (not just those age 50 or older) in 2000 exceeded the combined national expenditure on nursing home care and home health care by $133 billion. Harrow et al8 found a similar trend for Alzheimer’s disease care. The social and economic implications of caring for older adults will only become more prominent as the population ages. According to a recent report, it is more expensive to provide care to someone over age 65, and by 2030, the number of older Americans is expected to reach 71 million, or 20% of the population, compared to 4.1% of the population in 1900.9

The dedicated care and economic benefits that older informal caregivers provide are not without cost. Caregivers often face health risks. Several small controlled studies have shown that dementia caregivers have decreased measures of immunity10 and slower wound healing.11 A prospective study of elderly spousal caregivers showed that subjects reporting a high level of caregiving strain had a 63% higher 4-year mortality risk than noncaregivers.12 Caregivers also face workplace and financial issues. According to one report, caregivers over the age of 50 are at greater risk for job loss and lost job benefits as compared to caregivers under 34.1 A 1997 MetLife telephone survey and analysis found that caregiving leads to between $11.4 and $29 billion yearly in lost productivity costs.13 Finally, caregivers face significant emotional strain. In a 2001 online survey, about one in five caregivers of all ages reported having been told by a health professional in the last 12 months that they have depression, which is nearly twice the rate than in the general population.14

The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the epidemiology and consequences of caregiver depression, with respect to caregiver health and economic cost. A framework for the diagnosis and treatment of depression in caregivers will be presented, as well as barriers to effective management. Resources available to caregivers will be described.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CONSEQUENCES

Caregiver depression is a major public health problem. Several studies have shown a higher prevalence and incidence of depressive symptoms in caregivers than control populations. In a 1995 review of dementia caregiving, Schulz et al15 found that most studies reported elevated levels of depressive symptoms and clinical depression compared to population norms or control groups. In addition, several studies report an elevated rate of psychotropic medication use in caregivers compared to controls. Like dementia caregivers, caregivers in general have increased self-reported psychiatric symptoms and psychiatric illness.16 A prospective study of spouses of care recipients over age 65 showed that transitioning to increased caregiving was associated with increased symptoms of caregiver depression, as assessed by the CES-D.17

Depression has far-reaching effects on the health of caregivers. Depressed individuals are more likely to have coexisting anxiety disorder, substance abuse or dependence, and chronic disease such as arthritis.18 A retrospective analysis of patients enrolled in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys suggests that depressed patients are at greater risk for developing heart disease than healthy individuals, and that men with depression and heart disease have a higher death rate than women with the two conditions.19 Depression is also one of the most common conditions associated with suicide attempts, and older Americans, especially males, are disproportionately likely to succeed in these attempts.20

Depression is extremely costly in terms of disability,18 lost workplace productivity, health care utilization, and costs of associated illnesses. A recent study of the estimated economic burden of depression found that in addition to the $26.1 billon spent on the direct medical costs of depression, $51.5 billion was lost in workplace costs that include absenteeism.21 Suicide generated an additional $5.4 billion of mortality costs. In a large epidemiologic survey, depressive symptoms and, to a lesser extent, major depression, were associated with increased utilization of emergency department or medical consultations for emotional problems.22 Comorbid psychiatric and chronic physical illnesses incurred over 70% of total health care costs in a retrospective analysis of patients with depression.23

Although caregiver depression does not predict institutionalization of a dementia care recipient,24 interventions aimed at reducing caregiver depression can prolong the time to institutionalization. Several studies report a delay in nursing home placement after interventions aimed at reducing dementia caregiver psychological distress.25-28 This delay can help maintain high-quality home- and community-based personal care for care recipients.

The issue of the cost of home- and community-based care versus institutional residential care is not completely clear. Older studies, which did not compare home or community care and residential care directly, concluded that home- and community-based long-term care services usually raise health service use and cost,29,30 but a recent Canadian study argues that when compared directly, established home care can be less costly for stable clients than residential long-term care, even when taking into account a caregiver replacement wage.30 Thus, home- and community-based care may be cheaper, and interventions aimed at reducing caregiver depression may delay more expensive institutional care.

DIAGNOSIS AND “RISK FACTORS”

Although depression can be effectively treated, primary care providers often miss the diagnosis of depression.18 There are three major reasons why depression may be missed in older caregivers in particular. First, physicians commonly but erroneously assume that depression in an older patient is a normal response to aging or life events,4 such as the burdens of caregiving. Second, caregiver depression may be easy to ignore when focusing on the complex health care of the care recipient. Finally, and most fundamentally, education in geriatrics for primary care physicians, medical students, nursing students, and social workers is lacking and is unlikely to include discussions of caregiver depression. For example, only 3% of current medical students take any elective geriatric courses.9

As was previously mentioned, the criteria for the diagnosis of depression are listed in Table I.3-5 Practical tools for quickly identifying caregiver distress, including depressive symptoms, have also been developed for use in an office-based setting.5 It is important to rule out other causes of depressive symptoms in caregivers including drugs, medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, anemia, and chronic infection, and psychiatric conditions such as bereavement, adjustment disorder, anxiety disorders, and dementia. In the elderly, somatization, or the focus on physical symptoms, and pseudodementia, characterized by apathy that causes the patient to appear demented rather than depressed, may complicate the diagnosis of depression.4

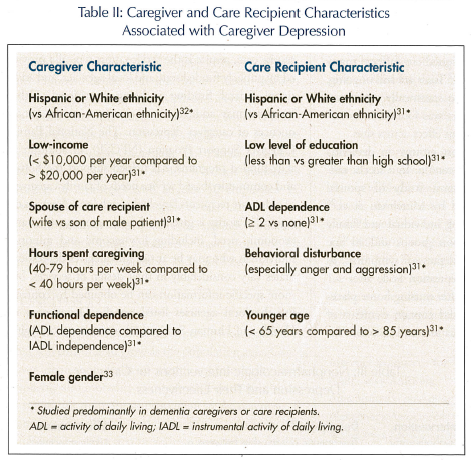

Several factors associated with caregiver depression are listed in Table II.31-33 These factors have been studied primarily in dementia caregivers and care recipients,31,32 except for gender effects, which were examined in a review and analysis of family caregivers in general (not only dementia caregivers).33 The factors listed in Table II may be useful if thought of as “risk factors” when evaluating caregivers and care recipients. However, these risk factors are greatly simplified and can only serve as a rough guideline. Cultural differences, environment,34 and different coping strategies33 may lead to different perspectives on caregiving, risks for developing depression, and expressions of depression.

TREATMENT

Although effective treatments are available for depressed caregivers, they do not always access these treatments. In addition, access may be limited by the health care provider. An online survey of caregivers in 2001 found that the physician’s office is often the first and only contact outside of friends and families for caregiving services, but less than half of caregivers felt supported by health care providers. In addition, only about half of physicians provided appropriate referrals.14 Although guidelines for working with dementia caregivers are published by organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association, only half of outpatient providers in one study implemented dementia caregiver support practices for at least half of their patients, and only about one-third of these clinicians routinely referred caregivers to the appropriate resources or routinely followed up.35 Furthermore, according to a report by Gray,36 caregivers may be less likely than their noncaregiving peers to seek care. Gray36 hypothesizes that this is because resources are disproportionately focused on the care recipient as compared to the caregiver.

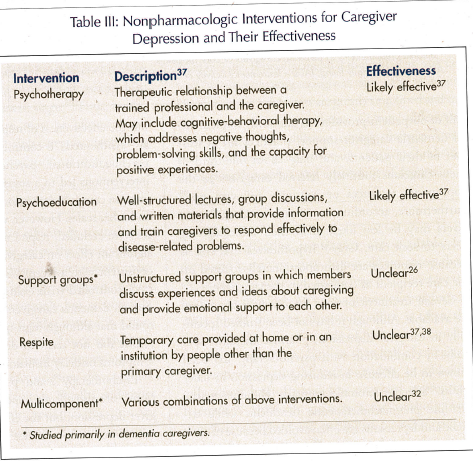

Several treatment options for caregiver depression are available. Although it has not been studied specifically in caregiver depression, pharmacotherapy, especially in combination with psychotherapy, has been shown to be effective in reducing depression in older adults.4 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are the first-line pharmacotherapeutic treatment, while tricyclic antidepressants are often avoided because of anticholinergic and alpha-adrenergic effects, which can be especially troublesome in the elderly. Unfortunately, pharmacotherapy is not always used appropriately by primary care providers.18 Nonpharmacologic interventions specifically targeting caregiver depression are listed in Table III.26,32,37,38 These interventions aim either to improve caregivers’ well-being and coping skills (eg, through psychoeducation or support) or to reduce the amount of care provided by caregivers (eg, respite or improvement of care recipient competence).37

Psychotherapeutic and psychoeducational interventions have been shown to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in caregivers, but the effectiveness of respite is less clear. Sorensen et al37 synthesized 78 controlled studies and found that psychoeducational, psychotherapeutic, and respite interventions led to a statistically significant improvement in caregiver depression, as assessed by the CES-D and other scales. However, when nonrandomized studies were excluded, respite no longer had a statistically significant effect on caregiver depression. This result is consistent with a recent Cochrane review of randomized, controlled trials examining the effects of respite care on dementia caregivers and care recipients, which found that although high-quality research was lacking, respite did not seem to decrease caregiver depressive symptoms or delay institutionalization.38

Psychotherapy39 and psychoeducational interventions40 are also effective, specifically for dementia caregiver depression, but the effectiveness of multicomponent interventions is less clear. The Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) study, a multisite randomized, clinical trial of the effects of multicomponent interventions on a diverse population of dementia caregivers and care recipients, included interventions designed to affect many domains, not just depression.32 Trials are still ongoing, but at 6-month follow-up, no statistically significant improvement in CES-D scores was found in a meta-analysis of the pooled treatment effect across sites.

The effectiveness of support groups on dementia caregiver depression is also uncertain. In a recent randomized, controlled, long-term study of spousal dementia caregivers published by Mittelman et al,26 enhanced counseling, including individual and family counseling, followed by support groups and ad hoc counseling resulted in fewer depressive symptoms, as measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale after 3.1 years of follow-up, including after nursing home placement. Counseling, however, did contain elements of psychotherapy and psychoeducation, and therefore the effect of support groups alone is difficult to distinguish. Overall, in both dementia and non-dementia caregivers, psychotherapy and psychoeducation have been shown to decrease caregiver depression, but the effectiveness of respite care, support groups, and multicomponent interventions are less clear (Table III).

RESOURCES

Several resources are available to caregivers, including respite care, direct home- and community-based services, and employer-based mechanisms.41 However, the emphasis of these services does not necessarily reflect their utility in treating caregiver depression. For example, despite mixed results of the effectiveness of respite care, respite is the service most typically provided by publicly funded state and local agencies, and additional federal funding is being considered. Other resources may address at-risk caregivers or the consequences of caregiver depression. The National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP), in addition to state-funded programs, has helped support the home- and community-based service needs of family caregivers of older care recipients largely through local Agencies on Aging.42 Priority is given to those in greatest social and economic need, including low-income and minority individuals who may be at risk for caregiver depression. States vary considerably in their design of services, but more specific information can be obtained by contacting the local agencies listed on the Department of Health and Human Services Administration on Aging website.43 Medicaid-related sources of funding also offer long-term care services to low-income families. The National Cash and Counseling Demonstration and Evaluation, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, enhances these Medicaid services in some states in a consumer-directed manner in which monthly cash allowances are given to caregivers to purchase goods, services, and counseling. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) of 1993, which guarantees workers in businesses with at least 50 employees 12 weeks of unpaid leave each year to take care of a seriously ill family member, has been expanded in some states to include longer durations of leave, protection for employees of smaller business, and paid leave.

CONCLUSION

Caregiver depression is clearly a public health problem that will continue to grow as the population ages. Caregiver depression leads to significant morbidity and probably also mortality in caregivers. Fortunately, there is significant room for improvement in the diagnosis of caregiver depression, and research on treatments is ongoing. The first step in addressing caregiver depression is to recognize the problem and talk with caregivers, either at their own visits or when accompanying care recipients to the health care provider’s office. Information about financial resources and referrals should be provided to caregivers. Providers must also offer the most effective treatments to caregivers, including pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and psychoeducation, and should be aware that the most effective interventions do not necessarily receive the most public funding. The wishes of care recipients, in addition to caregivers, should always be considered when addressing caregiver depression, as interventions may impact the type and nature of care provided.

The research reported in this article is supported by funds from the Division of State, Community, and Public Health, Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), Health Resources and Services Administration (HSRA), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under grant number 1 K01 HP 00071-02, and the Geriatric Academic Career Award for $58,009. The information or content and conclusion are those of the author, Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, MS, and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, the BHPr, HRSA, DHHS, or the U.S. Government.

Internet Resources for Caregivers

AARP: www.AARP.org

Administration on Aging: www.acl.gov

Alzheimer’s Association: www.alz.org

Alzheimer’s Foundation of America: www.alzfdn.org

National Family Caregiver Association: www.nfcacares.org

Recommended Readings for Caregivers

Astor B. Baby Boomers Guide to Caring for Aging Parents. New York, NY: Macmillan Spectrum; 1998.

Brammer LM, Bingea ML. Caring for Yourself While Caring for Others: A Caregivers Survival and Renewal Guide. New York, NY: Vantage Press; 1999.

Mace N, Rabins P. The 36-Hour Day. 3rd ed. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1999.

Wilkinson JA. Family Caregiver’s Guide to Planning and Decision Making for the Elderly. Minneapolis, MN, Fairview Press; 1999.