Clinical Perspective on Choice of Atypical Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Dementia, Part II

This is Part II of a two-part article. Part I appeared in the February issue of the Journal.

Atypical antipsychotics are utilized in the elderly to manage a broad spectrum of psychotic and behavioral symptoms. Recent Food and Drug Administration warnings regarding metabolic issues, cardiac conduction, and risk of cerebrovascular adverse events have put the clinician in a precarious position in managing patients with dementia with psychiatric and behavioral symptoms. However, there is significant literature supporting the general safety and efficacy of these agents. Part I of this article discussed the recent warnings associated with atypical agents. Part II profiles each of the six atypical agents available in the U.S market: risperidone, olanzapine, quetia-pine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, and clozapine. An algorithm is presented for choosing an atypical agent in the treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbance associated with dementia, keeping in mind the frail and medically complex elderly population typically found in long-term care settings. (Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging 2005;13[3]:30-38)

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

INTRODUCTION

The treatment of dementia with associated symptoms of psychosis and behavioral disturbance requires complex decision making regarding the appropriate, safe use and specific choice of atypical antipsychotic agents. The decision to use an atypical agent is based upon comprehensive evaluation, treatment of underlying medical conditions, use of nonpharmacologic behavioral interventions, and targeting symptoms that are likely to be responsive. The art of obtaining the desired clinical benefit often involves balancing anticipated pharmacologic effects of a given medication. Can the patient tolerate a more potent D2 blocking agent like risperidone without developing parkinsonism? Does the patient become hypotensive? Is sedation problematic or can it be utilized to promote a better nighttime sleep pattern? Is weight gain or the management of diabetes an issue? Do anticholinergic side effects associated with olanzapine or clozapine contribute to increased confusion? Increased understanding of the pharmacologic properties and clinical familiarity with the different personalities of the atypical agents allows the clinician to make better informed choices with a given patient.

Part II of this article offers a brief review of relevant studies of each of the atypical antipsychotic medications in the treatment of psychosis and behavioral symptoms associated with dementing illness. Risks and benefits of each agent are profiled in the context of treating the older patient. Finally, an algorithm is proposed to help guide clinical decisions in choosing an agent and subsequent management.

CLINICAL EVALUATION AND APPROPRIATE TARGETING OF SYMPTOMS

Use of atypical antipsychotics in this population is predicated on a number of factors consistent with best clinical practice. First, the adequate assessment of the patient’s medical, neurological, functional, and psychiatric status is completed. Second, there is an assessment of problematic behaviors, and an attempt to mitigate these problems is undertaken by addressing underlying medical issues, patient needs, and the use of enhanced structured environmental, social, and nonpharmacologic behavioral interventions. Third, while there are limited data to show significant impact on neuropsychiatric and behavioral symptoms, trials of cholinesterase inhibitors, memantine, or the combination should be considered in terms of potential impact on cognitive, behavioral, and psychiatric symptoms. Fourth, consider if the targeted symptoms or behaviors are likely to be responsive to an atypical agent. Appropriate target symptoms include verbal and physical agitation, hallucinations, delusions, suspiciousness, irritability, and hostility. Other behaviors such as wandering, hoarding, unsociability, poor self-care, screaming, and other stereotyped behavior may be less responsive.1,2

CONTROLLED AND CLINICAL STUDIES OF ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS IN DEMENTIA

Risperidone

Risperidone is the best studied of the atypical agents in the management of psychosis and behavioral issues associated with dementia. There have been four controlled trials of risperidone involving 1230 patients diagnosed with dementia (Alzheimer’s disease [AD], vascular dementia [VaD], or mixed) with behavioral symptoms and/or psychosis.3-6 Risperidone was shown in each of these studies to significantly improve symptoms of psychosis and aggressive behavior, and was relatively well-tolerated in dosages under 2 mg per day, with 1 mg per day found to be the average effective dose. Extensions of 12 months in the studies showed continued tolerance and benefit.

Olanzapine

Street et al7 conducted a 6-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of olanzapine in 206 nursing home patients with both AD and VaD with behavioral disturbance, with the best dose being 5 mg per day. Gait disturbance, especially at doses greater than 10 mg, was the most problematic adverse event and differentiated from extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS). Street et al8 followed up with an 18-week open-label study demonstrating ongoing efficacy and tolerability. De Deyn and associates9 conducted a similar 10-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of olanzapine with 652 patients with AD, and found the most effective dose to be between 2.5 and 7.5 mg. There were significant overall treatment group differences with olanzapine in increased weight, anorexia, and urinary incontinence. However, there were no significant differences of any other individual events, including EPS, cognition, vital signs, or laboratory measures, such as glucose, triglyceride, and cholesterol, in any olanzapine group relative to placebo.

Meehan et al10 evaluated the use of the new intramuscular preparation of olanzapine in patients with dementia with acute agitation in a double-blind study comparing dosages of 2.5 mg and 5 mg to lorazepam 1 mg and placebo. They found sustained benefit in terms of reduced agitation at 2 hours and at 24 hours for both olanzapine dosages in comparison to placebo, and sustained benefit at 24 hours in comparison to the lorazepam group. The lorazepam group showed benefit at 2 hours, comparable to the olanzapine group, but was not sustained at 24 hours. No significant differences between groups were found in terms of EPS, hypotension, or cardiac-corrected QT (QTc) interval changes. They concluded that the intramuscular preparation was both effective in reducing agitation and tolerated well in this patient group.10

In addition, there has been interest in response of other target symptoms such as mood and anxiety, as well as psychotic and behavioral symptoms in other dementia syndromes. Mintzer et al11 found significant improvement on behavioral anxiety scales in post hoc analysis of the Street study. Cummings et al,12 also in a post hoc analysis of the Street study, demonstrated benefit in psychotic symptoms associated with a subgroup of patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) without significant worsening of parkinsonian features. In an open-label trial of eight patients with DLB treated with olanzapine 2.5-7.5 mg, two patients showed significant improvement in psychosis with good tolerance, but three patients could not tolerate the medication at the lowest dosing, and three others showed tolerance but with minimal benefit.13

Quetiapine

Because of its remarkable low potential for inducing EPS, there has been significant interest and several open-label reports on the use of quetiapine in the elderly population, including patients with AD, DLB, and psychosis associated with Parkinson’s disease, and are well summarized by Tariot and Ismail.14 However, there has not been a published double-blind, placebo-controlled study with quetiapine in any of these populations. In general, the published studies, including several open-label studies of 52 weeks duration with comparisons to other treatments, showed relative efficacy in reduction of psychotic symptoms and agitation with relative low incidence of EPS. Zhong et al15 recently presented results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial looking at dosages of quetiapine at 100 mg and 200 mg versus placebo in patients with AD with psychosis and behavioral disorder. The 200-mg dose appeared to offer increased efficacy compared to both placebo and the 100-mg dose. No increased risk for cerebrovascular adverse events (CAEs) in this treatment group was found.15

Ziprasidone

There are no controlled studies of ziprasidone in elderly patients with dementia and secondary psychiatric symptoms. A case review series of open-label ziprasidone in three elderly patients with dementia suggests significant clinical improvement based on chart review and showed good tolerability. The patients showed minimal QTc prolongation at time of initiation compared to baseline electrocardiogram (EKG), no patients showed QTc prolongation > 500 ms, no orthostatic hypotension or syncope, and no significant drug–drug interactions. These patients were drawn from a larger series of 53 patients, most of whom had dementia, with similar safety efficacy findings.16,17

Aripiprazole

Aripiprazole is the newest atypical agent approved. It is thought to have a unique mechanism of action combining partial agonism of the dopamine D2 and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) 5-HT1A and antagonism of 5-HT2A receptors. There have been three 10-week multicenter, placebo-controlled trials evaluating aripiprazole in elderly patients with psychosis associated with AD. While these studies have been presented, they remain unpublished. De Deyn et al18 and Streim et al19 used flexible-dose (2-15 mg/day) with mean dosing of about 10 mg per day. Significant improvement was seen in the treated groups on some, but not all, measurements of psychosis.18,19 Breder and colleagues20 used fixed dosing of 2, 5, and 10 mg per day. Significant improvement was seen in psychotic symptoms in the 10-mg group. A pooled safety analysis showed relative good tolerability compared to placebo, with somnolence being the most common treatment-related effect.21 An open-label study of aripi- prazole in patients with drug-induced psychosis of Parkinson’s disease saw near resolution of symptoms in only two of eight patients enrolled, with the other six discontinuing treatment within 40 days, including two patients with worsening of their motor symptoms.22 The authors concluded that initial results were mixed but not encouraging.22

Clozapine

Clozapine has been extensively studied in drug-induced psychosis associated with Parkinson’s disease.23 There have been two controlled trials on long-term efficacy and tolerance that demonstrated efficacy in significantly reducing psychotic symptoms in patients with drug-induced psychotic symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease.14-26 While both trials demonstrated good tolerance and safety at average therapeutic dosages of 50 mg per day, there remains significant concern secondary to the risk of agranulocytosis, weight gain, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, pancreatitis, orthostatic hypotension, and anticholinergic side effects. There have been no controlled trials in management of behavioral symptoms or psychosis in AD.

DISCUSSION

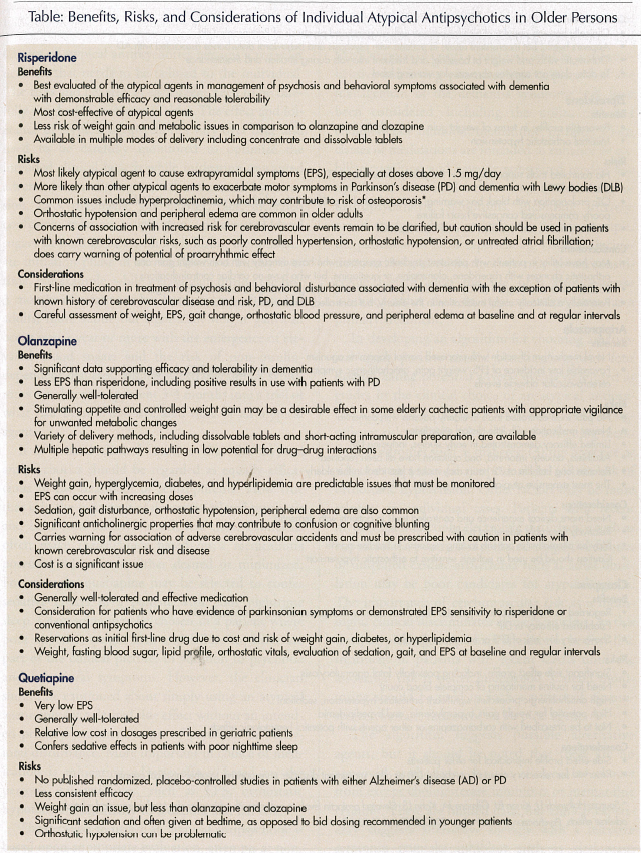

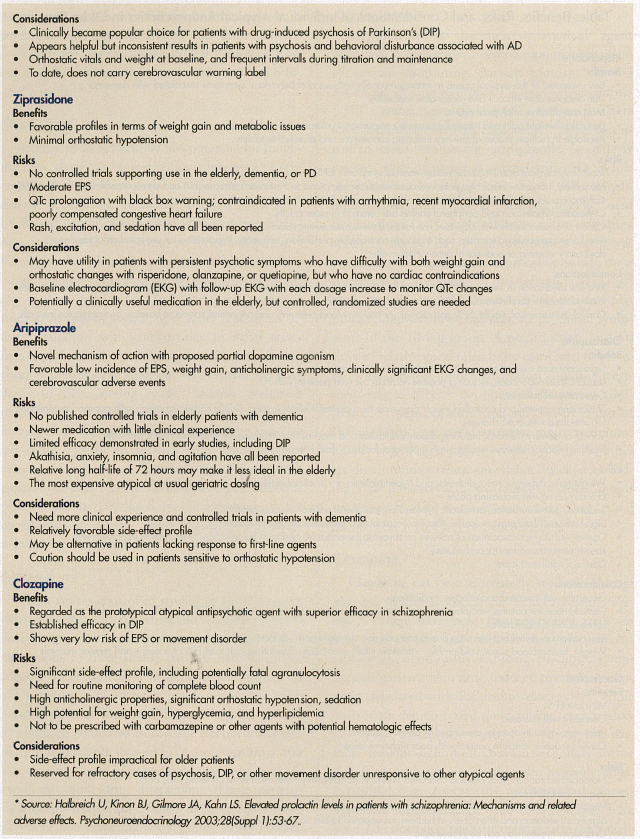

Choice of atypical antipsychotics remains a complex decision that needs to be tailored to the individual. The risks and benefits of each agent need to be carefully weighed in each case (Table). The effect and tolerance of atypical antipsychotics vary over time and need to be carefully monitored to optimize the intended clinical benefit while mitigating unwanted adverse events. Emergence of orthostatic hypotension, EPS, dysphagia, gait change, falls, increased confusion, sedation, weight gain, and elevated blood sugars all need to be monitored during the immediate initiation phase of treatment and routinely over time. For example, while weight gain during the first 3 months of treatment has been an area of focus in adults, more subtle but significant weight gain can occur over a year or more with the emergence of elevated blood sugars and the risk of non–insulin-dependent diabetes. Similarly, extrapyramidal symptoms may become apparent 3-4 months into a trial of what had been a well-tolerated dose of an atypical agent.

It is general clinical opinion that the atypical antipsychotics should be regarded as equally efficacious in the treatment of schizophrenia. How true that is in the treatment of dementia-related psychosis and behavioral issues is much less clear. Clinicians often make their choice based on a medication’s potential side effects, either desired or minimized. For example, quetiapine may be selected to confer sedative effects in a patient with poor nighttime sleep. Olanzapine may be chosen in a patient where poor appetite, weight loss, and failure to thrive are part of the clinical picture, in addition to psychotic and behavioral symptoms. However, the clinician should be cautioned about simply using an atypical agent only for a desired side effect without an intended primary treatment target of psychosis or behavioral disturbance. More important in choice of medication is mitigating adverse effects based on the person’s vulnerabilities, such as EPS, orthostatic hypotension, sensitivity to sedation, and fall risk.

The decision to utilize an atypical antipsychotic is based upon appropriate evaluation, attempts at nonpharmacologic behavioral, social, and environmental interventions, and determination of appropriate and likely responsive target symptoms. Ideally, a comprehensive enhancing pharmacologic approach to the management of the dementia syndrome will have been considered, including the utilization of a cholinesterase inhibitor, memantine, or both. These classes of medications are intended to enhance or stabilize cognition and have demonstrated modest but significant behavioral benefit over a wide range of neuropsychiatric symptoms including anxiety, mood, and psychotic symptoms.27-29 For example, the patient with DLB experiencing visual hallucinations and behavioral fluctuations may obtain considerable benefit with the use of a cholinesterase inhibitor rather than an atypical antipsychotic as a primary treatment.30

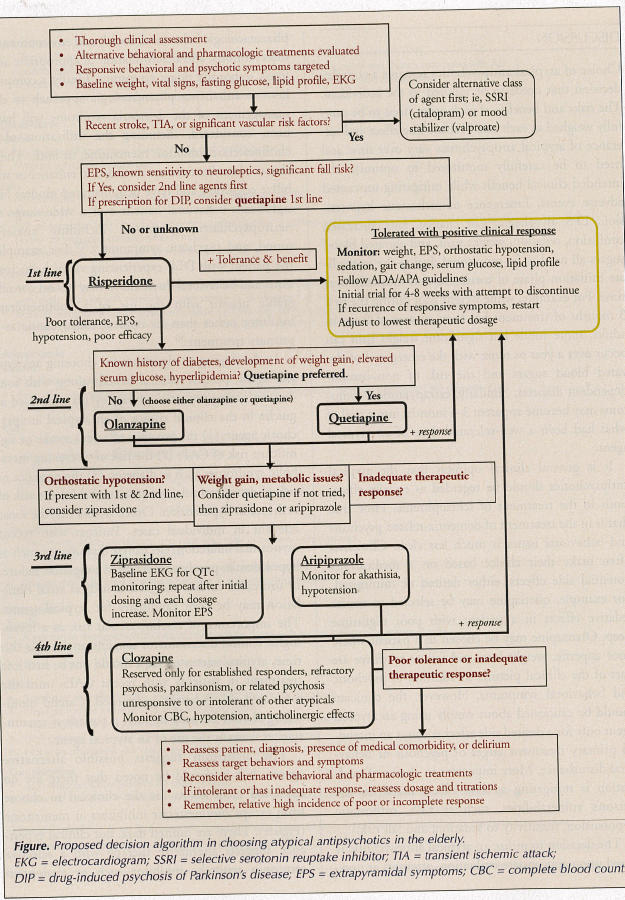

In developing an algorithm for choosing an atypical agent, positive clinical benefit along with four discriminating potential adverse events were used as guides in the clinical choice of an atypical antipsychotic agent: (1) the presence of recent stroke or significant risk of CAE; (2) the risk of worsening metabolic syndromes such as diabetes; (3) the presence or risk of extrapyramidal symptoms; and (4) the risk of orthostatic hypotension. Other factors may be more relevant in individual cases. Patients with recent myocardial infarction, electrolyte disturbance such as hypokalemia, poorly compensated congestive failure, or untreated cardiac arrhythmia such as atrial fibrillation may be poor candidates for atypical agents. The importance of cerebrovascular risk as a meaningful clinical discriminator remains unclear. At this time, atypical agents perhaps should not be first-line treatment in patients with recent CAEs until the associated risk is better understood. Careful monitoring should be used in such a patient if circumstances warrant the use of an atypical agent.

The algorithm suggests possible alternative agents, but it should be noted that there are no approved medications for the clinician to choose from except cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine (Figure). There are limited data, but clinical experience suggests alternative therapy with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor such as citalopram might be used first to target depressed mood, irritability, or nonspecific agitation.31,32 Anticonvulsants such as carbamazepine and valproate have also been employed to target agitation with mixed results and concerns with tolerability.33,34 A recent meta-analysis of the use of valproate in behavioral agitation associated with dementia concluded that low-dose valproate therapy conferred little benefit in the management of agitation, and higher doses were poorly tolerated.35 High-potency conventional agents in low dosages, such as haloperidol, remain a remote alternative, especially when psychotic symptoms are present. However, conventional agents present increased risk for EPS, tardive dyskinesia, and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and remind the clinician of the tolerability and safety benefits of atypical antipsychotics.36 In addition to the clinical issues, there remains a significant difference in cost of the atypical agents, not only in comparison to older conventional agents, but compared to each other at typical geriatric dosing.

Risperidone is almost one-fourth the cost of aripiprazole at relevant geriatric dosing. Risperidone likely emerges as a best first choice and reference agent, especially when the question of parkinsonism is yet undetermined in a patient. For patients with known parkinsonism or Parkinson’s disease, quetiapine may be the treatment of first choice. Olanzapine is a good intermediate alternative and may be a good choice for patients who do not tolerate a trial of risperidone. Ziprasidone, though it has no supporting controlled trials, presents with an attractive pharmacologic profile and may be an alternative for patients who demonstrate orthostatic hypotension with other agents. It can be monitored with baseline and subsequent EKGs after initial dosing and each dose titration. Aripiprazole has a growing database suggesting relative efficacy and favorable tolerance, and an adverse event profile including low risk for EPS and weight gain, and free of clinically relevant EKG changes. There is need for more clinical study and experience, but aripiprazole appears relatively safe and offers a reasonable alternative in patients in whom other agents have failed. Finally, clozapine, because of its relative toxicity and the burden of blood count monitoring, is now reserved for patients with movement disorders, for those in whom other agents for the treatment of psychotic symptoms have failed, or those who have been long-term established patients, such as patients with schizophrenia, with demonstrated tolerance and known clinical benefit.

CONCLUSION

There is a growing body of literature supporting the current clinical use of atypical antipsychotics in older patients with psychotic symptoms and behavioral agitation associated with AD and other dementing disorders. There has been increasing evidence of more uniformed and appropriate use and management of these agents in long-term care settings. Risperidone and olanzapine have been the best studied and have demonstrated both efficacy and relative safety in this population. There remains a need to better understand the significant and relevant management issues involving weight gain, diabetes, QTc prolongation, and the association of cerebrovascular events in treating elderly patients. The importance for careful initial evaluation, appropriate target symptoms, realistic treatment expectations, as well as close monitoring is fundamental in the safe and efficacious use of atypical antipsychotic agents.

Controlled clinical trials have underscored the difficulty in sorting out adverse events and their relationship to medication in a high-risk frail population of patients with AD and other dementias. Concern remains that recent FDA and other regulatory advisories regarding the use of atypical agents in elderly patients have served as major disincentives in further evaluating atypical antipsychotics and pursuit of approved indications in managing dementia syndromes. Recognition of the utility of these medications by the establishment of a clear-cut FDA approval for the treatment of psychosis and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia remains an important goal. Forthcoming data from the National Institute of Mental Health–sponsored Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) in AD trial will hopefully help establish treatment indications, clarify medication choice, and help us better understand and manage matters of safety.37 Finally, the interested reader is directed toward the recent publication of consensus expert guidelines on the indications and use of atypical antipsychotics in the elderly.38 A standard of care is emerging with attempts to clarify important factors in prescribing decisions pointing toward a more uniform approach to the overall management of patients with dementia-associated psychosis and behavioral disorders.

Dr. Keys reported that he has served on the speaker’s bureau for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer Inc, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Janssen, and Eli Lilly and Company.