Clinical Perspective on Choice of Atypical Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Dementia, Part I

This is Part I of a two-part article. Part II will appear in an upcoming issue of the Journal.

INTRODUCTION

Atypical antipsychotics are commonly prescribed for a broad spectrum of psychiatric illness in the elderly, including the off-label treatment of psychosis and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia. The clinician’s choice of which atypical agent to use or when to prescribe it has become an increasingly complex decision involving a growing appreciation of newer agents with unique pharmacologic profiles, potential adverse events, and relative costs. Recent expert opinion guidelines concluded that atypical antipsychotics are the first line in treating psychosis and agitation associated with dementia. While there was not a clear consensus on the treatment of agitation without psychosis, atypical antipsychotics were the most agreed upon choice.1 To date, there remains no Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved medication with an indication for the treatment of psychosis and behavioral agitation associated with dementia. A MEDLINE search of the literature demonstrates a significant body of literature regarding the use of atypical antipsychotics in patients with psychotic symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias. Atypical agents have been well studied in controlled trials demonstrating clinical benefit and a safer side-effect profile compared to older conventional antipsychotic agents.2-3

UTILIZATION OF ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS IN LONG-TERM CARE

Since the Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) regulatory guidelines have provided useful tools for both traditional and atypical antipsychotic medications that have led to an overall decrease in utilization and inappropriate use of antipsychotic medications. Recent reviews of use of antipsychotics suggest that over 90% of the prescribed use in the nursing home setting is appropriate according to OBRA-defined indications, dosing, and monitoring of outcome.4

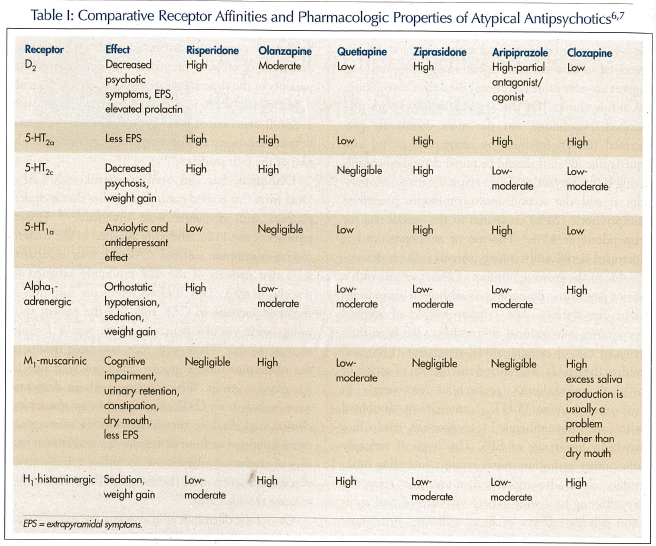

Liperoti and colleagues5 found that 62% of residents in the nursing home setting manifest significant behavioral symptoms associated with cognitive impairment. Of those residents with behavior disturbance, 18.2% were treated with an antipsychotic—11% received an atypical antipsychotic and 6.8% received a conventional agent—suggesting atypical agents are now more commonly used than conventional antipsychotics. Of the atypical antipsychotics prescribed, risperidone was the most commonly prescribed (66%), followed by olanzapine (25%) and quetiapine (6%). It should be noted that when considering both conventional and atypical agents, haloperidol is still the second most commonly prescribed antipsychotic (24%) compared to the overall rate for risperidone of 43%.5 The use of antipsychotics has increased significantly among patients without dementia due to the growing number of older persons with a major psychiatric illness such as schizophrenia in long-term care settings. The primary benefit of atypical agents over conventional antipsychotics has been their reduced risk of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) and tardive dyskinesia. The shared mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotics, preferential serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT2A) antagonism combined with varied dopaminergic D2 antagonism, results in a markedly lower rate of EPS. The atypicals variously affect other neurotransmitter systems, including histaminic, alpha-adrenergic, and muscarinic receptors, contributing to a wide variety of potential and common adverse effects such as sedation, orthostatic hypotension, peripheral edema, urinary retention and incontinence, constipation, dry eyes and mouth, and nonspecific gait disturbance (Table I).6,7 Seizures are a remote risk with all the atypical agents, and these agents should be used with appropriate caution in patients with known seizure disorder or lowered seizure threshold.

CEREBROVASCULAR ADVERSE EVENTS

Cerebrovascular adverse events (CAEs) are defined as suspected occurrence of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). Concern of an increased incidence of CAEs associated with atypical antipsychotics began with the results of a nursing home study that reported a significantly higher incidence of the risperidone treatment group compared to the placebo group.8 Based on pooled data of risperidone randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials of patients with psychosis and behavioral symptoms associated with AD, vascular dementia, or mixed dementia, it was found that 4% of patients in the risperidone-treated group (29/764 with 4 deaths) versus 2% in the placebo group (7/466 with 1 death) experienced a CAE. A significant difference between treatment and placebo groups was seen in only two of the four studies.2,9-12

Olanzapine has also been associated with CAEs. Data from five pooled controlled studies that included patients with dementia were analyzed.13-18 Fifteen patients of the 1184 randomly assigned in the trials to receive olanzapine suffered CAEs (1.3%), compared with two patients of the 478 randomly assigned to placebo (0.4%). This finding represents just over a threefold increase in CAE risk. For the patient subgroup with vascular dementia, there was a fivefold increase in risk. There were four associated deaths in the olanzapine-treated groups compared with one in the placebo group. When patients without dementia were excluded, no CAEs were found in an olanzapine clinical trial database that included 6545 olanzapine-treated patients without dementia. Age and known history of cerebrovascular disease, including a diagnosis of vascular dementia, were the most significant risk factors associated with CAEs.19

One of the dilemmas with assessing the risk of stroke in older populations is the lack of quality epidemiologic studies of stroke and TIA in the general population, with which to compare the risk as seen in this pooled sample.20 In an attempt to put the risperidone and olanza- pine studies in perspective, one would want to compare rates of cerebrovascular events, stroke, and TIA in the active and placebo study groups relative to age- and risk-matched data of the general population. In 1993, Bonita21 compiled and compared epidemiologic studies of stroke around the world, which were largely conducted in the 1980s, and found that stroke risk rises dramatically with age. There were significant differences from country to country, which may in part have been determined by differences in definition of stroke. In the U.S., incidence of stroke ranged from a low of 120 per 10,000 (1.2%) in a group of patients age 75-84 to a high of nearly 200 per 10,000 (2%) of patients age 85 or older. U.S. statistics were nearly 50% lower compared to the 85-and-older group living in Sweden, 400 per 10,000 (4%). It should be noted that these studies looked at stroke and not “stroke or TIA,” as CAE is defined. One would expect that the true incidence of CAEs is likely significantly higher than the studies included in the Bonita survey.21 Though the incidence of CAE is greater in both the risperidone- and olanzapine-treated groups compared to placebo, both the placebo and treated groups appear to have an incidence of CAE only slightly higher, comparable, or even less when compared to age-matched general population, depending on what region and study is used as comparison. Not surprisingly, the incidence of CAE in the risperidone studies showed variation between sites and countries, with the majority of CAEs being reported from an Australian site.

Herrmann et al22 conducted a retrospective population-based cohort study of patients over age 66 comparing users of conventional antipsychotics (n = 1015), risperidone (n = 6964), and olanzapine (n = 3421). Model-based estimates adjusted for covariates hypothesized that associated stroke risk revealed relative risk estimates of 1.1 for olanzapine (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.5-2.3) and 1.4 for risperidone (95% CI = 0.7-2.3). The study concluded that olanzapine and risperidone use were not associated with a statistically significant increased risk of stroke compared with typical antipsychotic use.22

The relationship of the use of atypical antipsychotics and CAE risk remains unknown, and, as others have pointed out, the interpretation of these findings needs to be approached carefully. The possible underlying pathophysiology linking atypical agents with CAEs remains unknown, but speculation has concerned either serotonergic effects on blood vessels, thrombotic risk, or perhaps alpha-adrenergic–mediated orthostatic changes. It should also be noted that of the CAEs reported, all were suspected to be ischemic in nature and no clear hemorrhagic events were reported.11,19 However, risk of CAE has not been clearly seen as a class effect, nor has the effect been seen in younger individuals without dementia in the olanzapine clinical trials. Schneider and colleagues23 presented an unpublished post-hoc analysis examining data from two controlled studies of quetiapine in elderly subjects with dementia and behavioral symptoms. They did not find an associated risk of CAEs in the quetiapine sample. To date, age and history of previous cerebrovascular disease appear to be the most significant associated risks in the study population, just as they are in the general population.

METABOLIC ISSUES

The risks for weight gain, hyperglycemia, development or worsening of diabetes, and elevation of lipids have been reported with all the atypical agents, and the FDA has chosen to apply a warning to the class as a whole. The mechanism by which atypicals promote weight gain, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia is not fully understood and is likely complex. Proposed mechanisms include increased appetite mediated by 5-HT2c and H1 receptor antagonism, excessive weight gain, increased insulin receptor resistance, reduced responsiveness of pancreatic cells, and reduced insulin secretion. With associated metabolic change, hyperglycemic states, hyperosmolar coma, ketoacidosis, and death have all been reported.24 Of equal concern is the ongoing management of patients who have shown clinical benefit but develop weight gain, elevated glucose, diabetes, or elevated lipid levels over the course of treatment.Incidence of relative risk of weight gain or hyperglycemia with a given individual agent or as a class of medications is not well defined, but incidence in controlled trials of 6-12 weeks suggests 5-12% of patients will show weight gain. The relative risk of weight gain or hyperglycemia in elderly patients compared to younger patients is not known. There is a consensus that olanzapine and clozapine are likely the most problematic in terms of potential for weight gain.25,26

There has been interest in determining how problematic atypicals have been in terms of metabolic issues in the long-term care setting. Goldberg27 found no significant weight gain in 50 nursing home patients recruited from three different facilities who were treated with risperidone and olanzapine. Patients in both groups lost weight over the 4 months of the study. Four patients taking risperidone gained greater than 5 pounds and no patients taking olanzapine gained weight.27 Elevations in leptin and serum triglycerides have been associated with weight gain with both olanzapine and clozapine, with relatively modest increases seen with quetiapine, and minimal elevations associated with risperidone.28

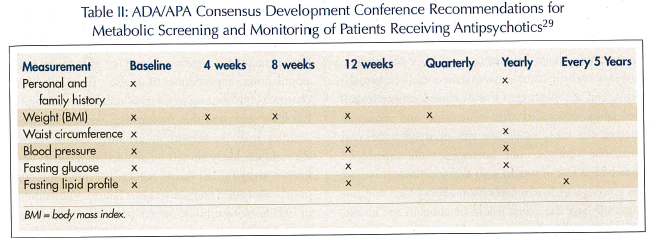

The Consensus Development Conference on Antipsychotics and Obesity and Diabetes developed recommendations on screening and monitoring of patients prescribed atypical antipsychotics (Table II).29 It was concluded that some of the atypical and conventional antipsychotics have clear associated risks of weight gain, diabetes, diabetic complications such as diabetic ketoacidosis, and dyslipidemia. Of the atypical antipsychotics, the panel concluded that olanzapine and clozapine showed the most significant risk of weight gain and metabolic changes, and quetiapine and risperidone showed less risk of weight gain and inconsistent impact on glucose and lipid metabolism. Ziprasidone and ari- piprazole have the lowest risk of weight gain and no significant risk of diabetes or dyslipidemia. Recommendations included careful screening of the patient’s medical and family history, baseline weight, vital signs, waist circumference, fasting glucose, and lipid profile. Weight should be followed monthly at the start of treatment and quarterly thereafter. Patients, family, or staff should be encouraged to check and record weights frequently. Education of patient, staff, and caregiver of the risk of metabolic issues, recognition of signs and symptoms of diabetes, modification of diet, and inclusion of nutritional consultation in high-risk patients may help mitigate metabolic issues.29

CARDIAC CONDUCTION

Both conventional and atypical antipsychotics can produce effects on the cardiovascular system.30 Prolonged cardiac-corrected QT (QTc) interval may lead to the potentially fatal ventricular tachyarrhythmia torsades de pointes. In controlled clinical trials, ziprasidone was found to prolong QTc interval to a greater extent than quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, or haloperidol. Ziprasidone was found to cause an average increase in QTc interval of 20 ms, and only two patients during clinical trials were known to have a QTc greater than 500 ms, an increased interval threshold associated with the generation of potentially fatal proarrhythmias.31 Risperidone also has received a warning of potential proarrhythmic effects, though no consistent QTc prolongation has been demonstrated in safety data, including in dosages two to three times the usual therapeutic dosages.32

Because of the potential association of QTc prolongation with ziprasidone, a warning was issued limiting its use in patients with comorbid cardiac conditions. Subsequently, there has been limited clinical use or research with this medication in the elderly and little data generated in terms of safety or efficacy in older populations. Ziprasidone may also affect potassium channels contributing to issues of repolarization, and it has been suggested that monitoring electrolyte abnormalities may be helpful in avoiding cardiac issues. Ziprasidone likely should be avoided in patients with known arrhythmias, recent myocardial infarction, and poorly controlled congestive heart failure. Vulnerability to QTc prolongation is unclear, but utilization of baseline and follow-up electrocardiogram (EKG) after initiation of the drug may help to provide a relatively safe way in which the clinician may screen and monitor appropriate use.33

COST

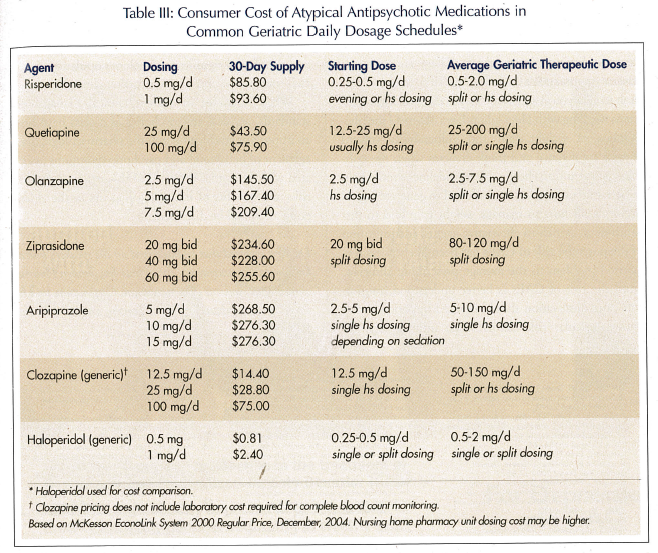

Atypical agents can cost 30-100 times the equivalent dosages of conventional agents (Table III). Adverse effects and potential problems with atypical agents, such as weight gain or diabetes, may in the long run contribute to significantly greater health care costs. Most pharmacoeconomic studies comparing atypical agents to older conventional antipsychotics have examined younger patients with schizophrenia, finding marginal or no economic benefit, but significant benefit in terms of quality-of-life issues. Revicki34 reviewed the cost effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia using clinical decision-making models, and concluded that only clozapine was a cost-effective medication in treatment-resistant schizophrenia, and that risperidone and olanzapine were at best cost-saving or cost-neutral in comparison to conventional agents, but did have better outcomes in quality-of-life measures. Edell and Rupnow35 looked at length of stay (LOS) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease who required acute hospitalization matched for severity of illness at time of admission. He compared LOS in risperidone- (12.3 days), olanzapine- (14.9 days), and quetiapine- (16.4 days) treated groups, finding significantly shorter stay when comparing risperidone to quetiapine at an estimated cost savings of $2014.20 based on daily hospital care rates.35

DISCUSSION

With the need to better define therapeutically useful treatments to mitigate behavioral and psychiatric symptoms associated with dementia, use of medications—particularly antipsychotic medications—continues to generate controversy as to risk versus demonstrable benefit. Atypical antipsychotics have been studied more extensively than any other class of agents in managing psychiatric and behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Meta-analyses of conventional antipsychotic agents have demonstrated significant but modest therapeutic advantage and effect size over placebo in this population.36 The controlled, randomized studies of the newer atypical agents have also shown modest but significant benefit.2 While therapeutic benefit has been found to be modest, no other class of medication has been able to show similar benefit in this population. Alexopoulos et al,1 in surveying recognized experts, found that atypical agents were the consensus choice in managing psychotic symptoms associated with dementia, and the most common choice in the treatment of behavioral symptoms associated with dementia without psychotic symptoms. These agents have been widely used in long-term care settings and with increasingly more uniform dosing and appropriate indications consistent with OBRA guidelines.

The advantage of an atypical antipsychotic is a therapeutic effect while minimizing extrapyramidal movement disorders and reducing the risk of tardive dyskinesia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome. These medications are not without significant adverse effects that can limit their usefulness. There are common adverse events, such as sedation and EPS, that are common to all atypical agents to varying degrees. Most clinicians working with older adults have observed the phenomena of weight gain and vulnerability toward glucose intolerance and frank diabetes when prescribing atypical antipsychotics. New guidelines should help to better identify patients at risk and to generate logical decisions on how to manage weight gain and to discontinue or switch to alternative agents. Identification of the potential risk of CAEs has been likely a less recognized problem to the average prescribing clinician. Until the risk of CAEs is better understood, caution and close observation should be used in patients with known vascular risk factors when utilizing atypical antipsychotics. As a class of agents, atypical agents all have the potential to prolong QTc interval. How age impacts upon vulnerability to such conduction changes and the clinical significance in older populations is not well-understood and deserves further clinical study.

When it comes to current clinical management standards, atypical antipsychotics as a class have been an important advancement in the pharmacologic management of behavioral and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia. In Part II of this article, individual risks and benefits of the atypical agents in the elderly population will be discussed.

Dr. Keys reported that he has served on the speaker’s bureau for Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer Inc, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and has served as a consultant for Pfizer, Janssen, and Eli Lilly and Company.