Clinical Areas of Liability: Risk Management Concerns in Long-Term Care

INTRODUCTION

Risk management is defined as a “facility-wide program designed to reduce preventable injuries and accidents and to minimize the financial severity of any claims.”1,2 With the growing epidemic of litigation against nursing facilities and their personnel during the last decade, risk management has become an important aspect of day-to-day patient care.3 Long-term care (LTC) facilities provide a variety of services to residents, and the potential for injury is significant in the frail, elderly population they serve. Caregivers on all levels must understand the spectrum of responsibilities required under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987, as well as monitoring of areas of high litigation risk. Moreover, a significant increase in lawsuits results as LTC facilities expand their participation in subacute care programs for sicker patients and offer increased medical services such as central line administration, patient-controlled analgesia, peritoneal dialysis, wound care, bariatric care, and chemotherapy.

The boom in nursing home litigation has adversely affected the practice environment in long-term care.4 Rising medical malpractice insurance premiums has caused some physicians to stop seeing patients in nursing facilities, and medical directors are often not covered for their administrative duties, leaving them vulnerable when litigation occurs. Many insurance carriers have ceased their coverage of nursing homes altogether. Premiums to nursing homes are drastically on the rise in most states, contributing to bankruptcy and causing many facilities to do business without coverage at all. These forces have threatened quality and access to care for frail elderly persons.5

Effective risk management requires identification of litigation-prone areas and implementation of preventive or corrective actions throughout a facility. The top targets in nursing home litigation are pressure ulcers, malnutrition and dehydration, and injurious falls. Other outcomes that are prone to litigation include elopement, adverse drug events, burns from unsafe smoking practices, untreated or undiagnosed changes in a medical condition, and improper discharge. Claims of negligence against nursing facilities can also involve assault by staff or another resident (resident-to-resident abuse), misuse of physical or chemical restraint, and violation of a resident’s rights, such as failure to obtain informed consent.6,7 This article will discuss major areas for litigation risk, and outline how LTC caregivers may proactively decrease their exposure should a lawsuit be directed against them or their facility.

THE DISCOVERY PROCESS

When a plaintiff’s attorney begins a lawsuit, documents are scrutinized, staff members and families give written statements or oral depositions, and theories are built that support their claims of negligence. This process is known as discovery. Major efforts will be made by the plaintiff’s attorney to uncover documentation discrepancies and other faults with the medical record. These include inconsistencies between a physician’s orders and medication administration, inadequate care plans, poorly documented food or fluid intake, and gaps in the nursing record. A search will also be made for errors, late entries, failure to inform the attending physician of change in condition, and failure to update or follow a care plan. Disgruntled former employees frequently serve as a source of damaging information against the nursing home.8 Attorneys will also look for care that fell below the acceptable standard, as defined by federal and state statutes (including OBRA), nursing facility policies, and the parent corporation’s regulations for member homes.

Although the medical director may have no firsthand knowledge of the incident, he or she may be asked to give a deposition to ascertain that if the medical director had been told of the incident when it occurred and had he/she intervened at that time, the clinical outcome could have been more favorable to the resident. For example, one case involved an advanced pressure ulcer that was not responding to the ordered treatment and that ultimately required an amputation. If the medical director had been contacted, a more timely evaluation and intervention by a specialist would have saved the limb.

The plaintiff attorney’s strategy can include suing the medical director for breaches of the standard by nurses and primary care physicians. The legal theory is based on OBRA statute 483.75, which states that the medical director is responsible for implementation of medical care policies and coordination of medical care in the facility. This new trend has caught many medical directors off guard, as they may not have coverage under either their medical malpractice policies or the insurance policy of the facility.

Other documents are frequently used for building a case of negligence. Federal and state surveyors often cite facilities for violation of regulations, resulting in administrative penalties up to $10,000 per day or termination of the Medicaid and Medicare provider agreements. Additionally, an increase in investigations by federal and state fraud units have resulted from many of these surveys that have ended in significant deficiencies being noted. These deficiencies and citations are easily obtained by plaintiff attorneys on the Internet (specifically the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] Nursing Home Compare website) and from the Freedom of Information Act, and have been used in court to build a case of negligence against a nursing home.9 For example, if the case involves an injurious fall, citations regarding maintenance of safety, prior to the plaintiff’s injury, will be used to build a case of systemic negligence against a facility.

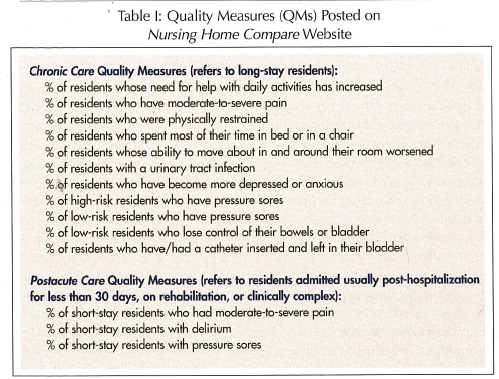

Review of public statistics can assist attorneys in preparing a lawsuit against a facility. As part of the Nursing Home Quality Initiative (NHQI) launched by CMS in 2001, 14 Quality Measures (QMs) have been released to the public on the Nursing Home Compare website (Table I).10 The QMs are derived from information submitted on the facility’s Minimum Data Set, the federally mandated assessment form. The purpose of posting the QMs is to allow the public to decide nursing home quality when placing a loved one, thus promoting “market pressure” to drive quality improvement. Many experts remain skeptical about this system because of inherent inaccuracies in the data as well as potential misinterpretation by laypersons. However, the flood of public information has alerted the public to concepts of quality care, and assisted in opening the gates to the current trend of litigation.

THE BEST DEFENSE

The best defense against litigation is improved quality of care. To reach this goal, nursing home owners, administrators, and employees must develop a vested interest in addressing and attempting to improve care and work together. This teamwork must include the presence and active participation of the attending physician and the medical director, and be carefully orchestrated so that all team members understand the mission and the methodological steps followed to improve care within the facility. In addition, staffing levels should be reviewed for their capacity to deliver appropriate quality of care. Each team member should be aware of the litigation risk in caring for chronically ill persons in nursing homes, and proactively maintain quality and limit exposure of themselves and the facility.

COMMON RISK-PRONE ISSUES

We will examine several common risk-prone issues and outline steps that caregivers can take to decrease litigation risk.

Falls and Fall-Related Injuries

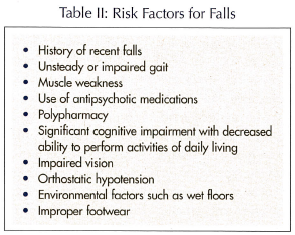

Falls and fall-related injuries to LTC residents remains one of the most common risk management concerns for nursing facilities. The incidence of falls in nursing homes is 1.6 falls per bed per year.11 Because of frailty and multiple comorbidities in the nursing home population, many residents are at risk for falls and fall-related injuries (Table II). Fall-related injuries frequently lead to major disability and mortality. An injurious fall can set into motion a spiral of physical decline that may result in other poor outcomes months later. For example, a fall with hip fracture needing operative repair can result in immobility, depression, and incontinence that can contribute to pressure ulcers, sepsis, and death. Though sometimes resulting from negligence, injurious falls occur even in the best of circumstances. Some complications are avoidable with good care, while others are unavoidable. Lawsuits commonly arise that attribute the injurious fall to negligence on the part of the facility, and point to the complications of the event as continued evidence of neglect.

Falls and fall-related injuries to LTC residents remains one of the most common risk management concerns for nursing facilities. The incidence of falls in nursing homes is 1.6 falls per bed per year.11 Because of frailty and multiple comorbidities in the nursing home population, many residents are at risk for falls and fall-related injuries (Table II). Fall-related injuries frequently lead to major disability and mortality. An injurious fall can set into motion a spiral of physical decline that may result in other poor outcomes months later. For example, a fall with hip fracture needing operative repair can result in immobility, depression, and incontinence that can contribute to pressure ulcers, sepsis, and death. Though sometimes resulting from negligence, injurious falls occur even in the best of circumstances. Some complications are avoidable with good care, while others are unavoidable. Lawsuits commonly arise that attribute the injurious fall to negligence on the part of the facility, and point to the complications of the event as continued evidence of neglect.

To prove negligence, plaintiff attorneys scrutinize care plans and physical therapy notes to detect whether inadequacies can be “linked” to the subsequent fall and injury. Attorneys will carefully review the written order, assessment, care plan, application, and monitoring of any restraint that was in place to note deviations from the care plan or orders. Incident reports and accident investigations are scrutinized for inconsistencies, as well as the timing and thoroughness of physician evaluations.

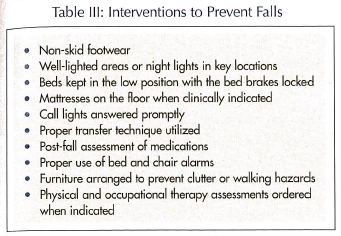

Facilities and caregivers can take specific steps to minimize exposure when fall-related injury arises. It is important to assess new admissions for fall risk and maintain a fall prevention program. For residents identified as high-risk, the care plans must reflect efforts to reduce falls in an individualized and resident-specific fashion. For residents who fall or have a change in a medical condition, new assessments should be completed and the care plan adjusted accordingly. The fall prevention program should include a component to educate the resident, family, and staff concerning fall prevention and an interdisciplinary approach promoting a safe environment within the facility. Injurious falls should be promptly assessed by appropriate medical personnel, and incident reports should be generated. Interventions that need to be explored to prevent falls in the LTC resident are listed in Table III.

Facilities and caregivers can take specific steps to minimize exposure when fall-related injury arises. It is important to assess new admissions for fall risk and maintain a fall prevention program. For residents identified as high-risk, the care plans must reflect efforts to reduce falls in an individualized and resident-specific fashion. For residents who fall or have a change in a medical condition, new assessments should be completed and the care plan adjusted accordingly. The fall prevention program should include a component to educate the resident, family, and staff concerning fall prevention and an interdisciplinary approach promoting a safe environment within the facility. Injurious falls should be promptly assessed by appropriate medical personnel, and incident reports should be generated. Interventions that need to be explored to prevent falls in the LTC resident are listed in Table III.

It is accepted in the medical community that physical restraint does not prevent falls or injuries, or enhance patient safety. Maximization of function and psychosocial well-being indeed precludes the use of physical restraint. Despite this, attorneys frequently attribute injurious falls to lack of physical restraint. Physical restraint in the nursing home is highly regulated, and these regulations provide a yardstick against which care in the nursing home is measured. Regulations promote the use of less restrictive interventions, and when restraint is used there must be informed consent, physician’s order, and continued reassessment for appropriateness of use. Nursing notes should document the reason for the restraint, release times, toileting times, and ambulation frequency. Consideration of reduction or discontinuation of restraint should be an ongoing issue during care plan meetings.

Any time a side rail prevents a resident from freely exiting the bed, it is considered a restraint. Types of injuries attributed to side rails include head or limb entrapment, strangulation, and asphyxiation. Staff members need education concerning federal and state regulations governing the restraints, and training must be given to new employees prior to caring for individuals with restraints. Documentation of such training should be maintained in a central file.

Chemical Restraints

Chemical restraints are centrally-acting medications used to sedate a resident and are not clinically indicated by the underlying condition. Chemical restraints are sometimes employed for the convenience of staff to “keep the resident quiet.” The use of chemical restraints is prohibited by federal regulations. The key in deciding if a medication is being used as a restraint is delineating appropriate use of psychoactive medications justified by specific medical or psychiatric diagnoses. The consulting psychiatrist and pharmacist can be helpful in identifying medications that can be reduced or eliminated. Importantly, they can also assist the attending physician in selecting the class of medication clinically indicated for specific behavioral problems that have the potential to respond to pharmacologic intervention. Responding in a positive and timely manner to families’ inquiries or complaints regarding excessive use of medication can be an effective method of addressing overmedication concerns. In all cases of psychotropic medication use, side effects must be properly monitored.

Nutrition and Hydration

The actual prevalence of dehydration and malnutrition is not known, but dehydration remains the most common fluid and electrolyte disorder among the elderly.12 Identification of residents with poor oral intake should be a priority for nursing staff. Constructing realistic care plans during meetings that include family members is the best way to set goals for residents in whom nutrition and hydration are an ongoing challenge. Advance directives regarding artificial nutrition and hydration should be sought early rather than waiting for crisis situations.

Potential areas of liability include unexplained weight loss, failure to consult family members regarding intervention for weight loss (including feeding tubes), and worsening of a pressure ulcer or infection due to the concurrent presence of a malnourished or dehydrated state. Key assessments include accurate weights and determination of caloric intake. Documentation in the medical record of food and fluids is critical, and the attending physician should be notified of significant weight loss or poor oral intake. This notification should be recorded in the medical record. If weight loss continues despite all interventions, the family needs to be notified and involved in any decisions. These discussions should also be recorded in the medical chart. Any tube feeding formula should be reviewed by the physician and dietitian for adequacy of its caloric content.

Dysphagia, or swallowing dysfunction, is a frequent condition in late-stage dementia or after stroke. Persons with swallowing disorders can present a challenge for staff to provide adequate nutrition and hydration without the use of a feeding tube. Early assessment by a speech/language therapist is important when managing persons with dysphagia. Adequate staff needs to be assigned to help with feeding of individuals requiring more time or assistance if weight loss is to be avoided. The facility dietitian also needs to be an integral part of any planning for at-risk residents. Alternatives to feeding tubes include frequent, small-portion meals, finger foods, snacks, high-calorie supplements, and hand-feeding. Identifying favorite foods and liquids can also help to maximize nutritional intake. When possible, avoid the use of pureed diets or cold meals, as they can be unappetizing and may lead to decreased intake.

Pressure Ulcers

Litigation regarding pressure ulcers has risen dramatically since the passage of OBRA ’87.13 Lawsuits related to pressure ulcers have drawn a great deal of attention due to high payouts, settlements, and jury verdicts. The concept that all pressure ulcers are preventable is often cited as the legal standard. However, even in the best of circumstances, pressure ulcers have not been eliminated, and few experts agree that all ulcers are preventable.14,15 Pressure ulcer prevention is a matter of risk assessment and implementation of pressure relief measures, mobilization, and nutrition.16,17 Although pressure ulcers are time-consuming and expensive to treat, an organized and systematic approach can make the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers an attainable goal, while reducing legal liability for the facility and staff.18

Photographs of wounds can be a valuable addition to a risk-management program in a nursing home, but if not used correctly, they can be a detriment. They are extremely helpful when residents are admitted from other facilities with ulcers, providing proof that the ulcer was acquired elsewhere. However, photographs taken on admission or at the time of first diagnosis, while helpful in documenting the presence and staging of these ulcers, does not reduce the facility’s obligation to prevent their progression. For this reason, the medical director and/or director of nursing should review the appropriateness of new admissions to determine if proper resources are present to treat pre-existing pressure ulcers.19

Proper photographing and sequential documentation of ulcer progression can be useful in serving as an objective yardstick to the effectiveness of the care plan and ordered treatments. However, if there are gaps in the treatment record, these may be used to indicate that “no care at all” was given. If staff members fail to document treatments, such treatments are often assumed, for legal purposes, as not done.19 Regardless of whether photographs are used, good nursing assessment and documentation regarding all pressure ulcers is a critical component of providing good care and reducing legal liability.

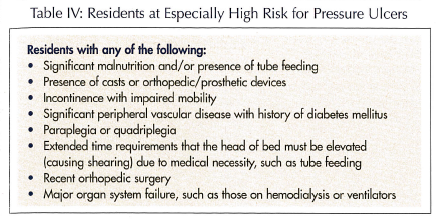

Risk management programs for pressure ulcers should begin with assessment for propensity to develop these lesions. There are several standardized forms available, including the Braden and Norton scores. These assessment scales should be completed in a timely and accurate manner, after admission and whenever there is a change in condition. If the resident is considered to be “ at risk,” this should be addressed in the care plan with timely and adequate pressure relief and nutrition. The pressure ulcer risk assessment scales can work to the facility’s disadvantage if: (1) the scale is completed late; (2) the scale is inaccurate; (3) persons determined to be at risk are not given appropriate pressure relief; and (4) the scale states “no risk” when the resident has a pressure ulcer. Residents who have any of the characteristics listed in Table IV should be considered at special risk for pressure ulcers, despite findings of a risk assessment scale.

Physicians can do proactive risk management with pressure ulcers by examining the resident and documenting the physical examination and wound care choices. Physicians frequently do not examine the wound and when they do, complete wound descriptions are not written. One of the most important elements of risk management for physicians is honest and open communication with the family regarding the presence of a pressure ulcer.

Medication Errors and Polypharmacy

Medication errors remain an ongoing challenge for LTC health care providers. A recent report cited by the Institute of Medicine showed that for every dollar spent on drugs in nursing facilities, $7.6 billion per year in nursing homes is spent on drug-related morbidity and mortality, of which $3.6 billion has been estimated to be avoidable.20 Many of the problems that develop in nursing facilities relate to the total number of medications being prescribed for this frail, older population that were initially ordered by other physicians and, many times, the clinical reason for their continued use is either obscure or no longer appropriate.

All health care providers and nursing staff need to be aware of the clinical indication for the drug (which should be written in the order), its proper dosage range, potential minor and serious side effects, common drug–drug interactions, and facility protocols dealing with the evaluation of potential problems from the drug’s administration. Frequently, vending pharmacies insist on their nursing facility contracts being “held harmless” in any subsequent lawsuits relating to all ordered medications. Proper strategies to deal with polypharmacy, medication errors, and side effects need to be incorporated into the facility’s continuous quality improvement process and risk management programs.

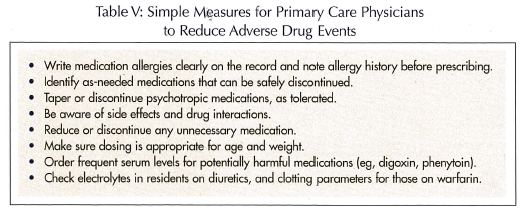

Attending physicians need to review all medications when accepting new admissions to a nursing facility and determine which are clinically indicated for continued use before they are ordered from the pharmacy. The absence of records or the failure to examine a new admission is not a defense for untoward effects that result from the use of medications. Physicians can follow some quick rules for minimizing the risk of adverse drug events in their nursing home patients (Table V).

Wandering and Elopement

Accurate statistics do not exist on the incidence of wandering and elopement behaviors, but in general, elopement risk seems greatest during the first 72 hours following admission. The key is to recognize the risk factors that would identify a resident for wandering or elopement risk at the time of initial assessment. Facilities should not rely only on hospital transfer information but complete their own wandering/elopement assessment and interview key family members to help identify those high-risk individuals who need monitoring. Medical directors need to review all facility policies on elopement and participate in or facilitate a mock elopement training exercise to familiarize the staff with emergency procedures to follow in locating a missing resident.

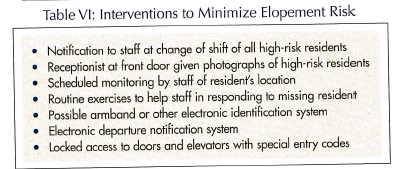

Frequently, there are clues to a resident’s propensity to elope. The first is history, and if a family states that the resident wants to escape, this should be taken seriously. Prior elopement events are often a good predictor of future behavior. Residents tending to elope often loiter around a locked door, waiting for an exit opportunity. Identification of those residents at risk for wandering, combined with a care plan that involves all staff members in the monitoring process, can help to reduce elopement or the injury from elopement-related events. Interventions to minimize elopement risk are presented in Table VI.

Frequently, there are clues to a resident’s propensity to elope. The first is history, and if a family states that the resident wants to escape, this should be taken seriously. Prior elopement events are often a good predictor of future behavior. Residents tending to elope often loiter around a locked door, waiting for an exit opportunity. Identification of those residents at risk for wandering, combined with a care plan that involves all staff members in the monitoring process, can help to reduce elopement or the injury from elopement-related events. Interventions to minimize elopement risk are presented in Table VI.

CONCLUSIONS

Many adverse events in nursing homes result in lawsuits, and physicians who work in these environments should proactively protect themselves with good relationships with family members and adequate documentation. Risk-prone events include injurious falls, malnutrition and dehydration, adverse drug events, pressure ulcers, wandering and elopement, inadequate documentation or failure to record treatments, and overuse/misuse of psychotropic medications. Some events are unavoidable even in the best of circumstances, but others are accompanied by such issues as understaffing, poor quality of care, and inaccurate or incomplete transfer of information to and from the acute care setting.21 Risk management, in the end, goes hand in hand with quality care and needs to be a highly visible aspect of the nursing facility’s operations.

Family education and good communication skills remain key ingredients to improving care and reducing lawsuits in nursing homes.22,23 Good risk management within a nursing facility requires the enthusiastic and unqualified support of the administrator, medical director, and director of nursing if it is to succeed. Monitoring of the care being delivered is a fluid, ongoing process that must empower supervisors and staff to be able to respond to care issues as they arise. The American public has a long history of expecting the very best from its health care system, and the LTC sector will be no exception to these high expectations.