Persistent Delirium Secondary to Lithium Toxicity in a Patient with Dementia Due to Traumatic Brain Injury

Introduction

Delirium is a frequent occurrence in patients with dementia.2 Behavioral symptoms associated with dementia on occasion necessitate clinicians to choose agents with significant side effects including delirium. A serious complication of lithium therapy is acute lithium intoxication, which can include persistent neuropsychologic sequelae.3 We describe a case of lithium intoxication in which the patient’s delirium did not improve for 2 weeks after normalization of his blood lithium level. Subsequent treatment with risperidone was associated with significant improvement in delirium-related symptoms. Persistence of delirium following acute medical hospitalization is common, and a high rate of 55% has been reported at 1-month follow up evaluation.4

Case Presentation

Mr. A, a 53-year-old man, was admitted to a psychiatric unit with a 1-month history of increasing confusion. Approximately 18 months before admission, he sustained a skull fracture with intracranial hemorrhage. He underwent rehabilitation and simultaneously alcohol detoxification for treatment of his 30-year history of alcohol dependence. Afterward, Mr. A continued to report persistent memory and behavioral problems (impulsivity and intermittent auditory and visual hallucinations) and was diagnosed as having mild posttraumatic dementia. His other medical problems included seizure disorder, hepatitis, hypertension, and a benign nasopharyngeal mass.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Traumatic Brain Injury in Elders

Talking About Mental Illness in Long-Term Care: "But She's So Depressing"

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Approximately 6-8 weeks before the index episode of “confusion,” Mr. A presented to the clinic with impaired sleep, rapid speech, hyperactivity, constant pacing, irritability, impulsivity and emotional dyscontrol, visual hallucinations, and increased alcohol use without confusion. His Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was 26. He was diagnosed with mood disorder (mania) secondary to general medical condition (traumatic brain injury), placed on lithium 300 mg BID and quetiapine 25 mg TID, and instructed to stop his use of alcohol. Lithium carbonate was reluctantly chosen because of a previous history of “allergic reaction” to divalproex sodium, history of hepatitis, and a therapeutic level of carbamazepine.

One month after starting lithium, Mr. A’s lithium level was 0.6 mEq/L and his alcohol use had decreased to 1-2 cans of beer per week (substantiated by his wife); his symptoms of mania persisted. Dosage of lithium and quetiapine was increased to 300 mg TID and 100 mg HS, respectively. Mr. A was admitted to the psychiatric unit 3 weeks later with sudden worsening of agitation and previous behavioral symptoms, development of confusion, disorientation, hallucinations, and decline in cognition.

Mr. A had abstained from alcohol for 10 days before admission, as reported by his wife. He did not show any clinical signs of alcohol withdrawal including absence of autonomic hyperactivity. Metabolic workup revealed normal liver enzymes, renal function, electrolytes, thyroid studies, rapid plasma reagin test, vitamin B12, and folate. Complete blood count showed a macrocytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Carbamazepine and phenytoin levels were normal. Lithium level was 1.71 mEq/L, and ammonia level was elevated (72 mol/L). Lithium toxicity was diagnosed, the patient was admitted in a delirious state, and lithium carbonate was discontinued.

A magnetic resonance imaging scan revealed bilateral frontal and temporal encephalomalacia and gliosis, consistent with chronic posttraumatic changes. Electroencephalographic findings implied abnormal sleep-wake cycles attributable to frontal intermittent rhythmic delta activity. Diffuse slowing of background rhythms suggested diffuse neuronal dysfunction, as seen in toxic or metabolic encephalopathies. Mr. A’s admission medications included carbamazepine 600 mg in the evening and 200 mg in the morning, phenytoin 300 mg HS, quetiapine 100 mg HS, fluticasone nasal spray 50 g BID, fosinopril 20 mg BID, furosemide 40 mg QD, magnesium gluconate 500 mg QD, multivitamins 1 tablet QD, folate 1 mg QD, and thiamine 100 mg QD. Each of these medications was continued and lithium was discontinued.

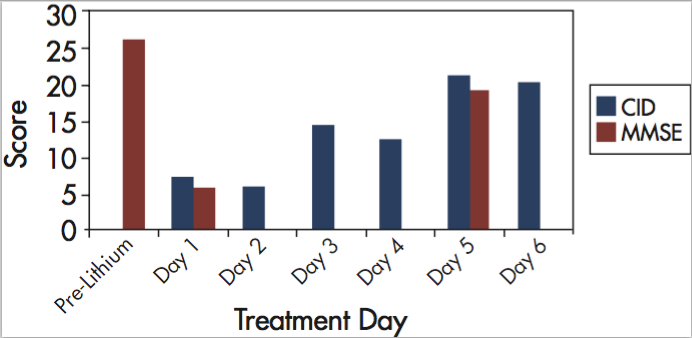

Mr. A continued to have confusion, fluctuation of symptoms of behavioral disturbance, and cognitive deficits relative to his baseline. In the absence of improvement on quetiapine, it was later  discontinued. Ten days later, Mr. A’s blood ammonia and lithium levels had normalized, but his behavior, function, and mental status remained impaired relative to preadmission status (Figure). When all symptoms of delirium persisted for another week, Mr. A was enrolled in an open-label risperidone trial to treat his persistent delirium.

discontinued. Ten days later, Mr. A’s blood ammonia and lithium levels had normalized, but his behavior, function, and mental status remained impaired relative to preadmission status (Figure). When all symptoms of delirium persisted for another week, Mr. A was enrolled in an open-label risperidone trial to treat his persistent delirium.

At the time of study enrollment, Mr. A’s Delirium Rating Scale (DRS)5 score was 26, Cognitive Test for Delirium (CTD) score6 was 7, and MMSE score was 6. He received oral risperidone 0.5 mg BID. Over the 6-day duration of the study, he showed improvement on all parameters of behavior and cognition as measured by the DRS, CTD and MMSE. Specifically, improvements were noted in perceptual disturbance, hallucination type, psychomotor behavior, sleep-wake disturbance, mood lability, and cognition. On day 3 of the trial, the patient’s spouse and hospital clinical staff noticed Mr. A’s improvement.

Psychiatric symptom severity and variability decreased. His CTD score improved to 14, with better orientation, attention span, memory, and comprehension. His DRS score also improved to 8. No extrapyramidal symptoms, excessive sedation, or hypotension was noted. Risperidone dosage was decreased to a maintenance dosage of 0.25 mg BID, in accordance with the study protocol, which required a DRS score of 12 or lower before decreasing the dose.

On the last day of the study (day 6), Mr. A was oriented to month, day, place, person, and year; his conversations were appropriate; he was attentive; and his sleep quality had improved. His DRS score had improved to 7, and he exhibited no adverse effects from risperidone. All aspects of the CTD (orientation, attention span, memory, comprehension, and vigilance) improved to a score of 21 (Figure). Over the trial period, the Karnofsky Scale of Performance Status documented a 20-percentage-point increase in performance status.

At follow-up approximately 6 months after discharge, Mr. A was not manic, and his MMSE score was stable at 17 to 19 on recent visits. The patient was receiving risperidone 0.5 mg BID, carbamazepine 600 mg BID, and his other nonpsychotropic medications to control the behavioral symptoms, mania, and agitation that had been present before the lithium toxicity.

Discussion

Despite several decades of experience with lithium in the treatment of bipolar disorder, lithium intoxication remains a clinical concern. The therapeutic window is narrow, and adverse effects become more common and more clinically important with increasing doses.3 Serious adverse effects occur most often at lithium plasma levels above 1.2 mEq/L;7 however, they have been reported at normal therapeutic levels8,9 and can occur during any period of lithium therapy.10

Neurotoxicity is more common in patients with risk factors (eg, organic brain disorder) and in patients taking concomitant drugs that can increase lithium levels and potentiate adverse effects (eg, carbamazepine, some diuretics).7,11 Thus, our patient was particularly at risk for lithium toxicity. Moreover, use of a relatively higher starting dose of lithium due to severity of the symptoms increased the risk of toxicity in our patient. Acute lithium toxicity can include encephalopathy, delirium, and extrapyramidal signs, with disorientation, drowsiness, fluctuation in consciousness, tremor, ataxia, hyperreflexia, and rigidity.3,10

Neuropsychologic sequelae, commonly involving cerebellar signs and sometimes cognitive dysfunction, can persist for several weeks to months in some patients after lithium is withdrawn, and infrequently can be permanent.10,12 This is a complex case with multiple factors potentially contributing to delirium besides lithium intoxication. While lithium toxicity appears to be the putative etiology, the role of preexisting dementia due to traumatic brain injury (TBI), longstanding history of alcohol dependence, and underlying seizure disorder and other metabolic abnormalities contributing to persistence of delirium is likely. Elevated ammonia level was considered unlikely to have contributed to persistence of delirium because delirium persisted despite normalization of ammonia.

Collateral history of abstinence of at least 10 days, sparing use of 1-2 beers per week for more than 3 weeks prior, along with absence of signs of autonomic hyperactivity on admission and persistence of delirium for 2 weeks into the hospital, essentially ruled out alcohol withdrawal as the potential confound. While, autonomic hyperactivity can be suppressed by anticonvulsant medications, EEG findings of diffuse slowing suggested metabolic etiology rather than alcohol withdrawals. Atypical presentation of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and neurotoxicity with the combination of antipsychotics and lithium was considered, but it was not suspected to be likely from the clinical presentation without fever, leukocytosis, rigidity or renal impairment. However, the “lag phase” between normalization of lithium level and clearing of the lithium level from intracellular tissues may have led to persistence of delirium.

Due to persistence of delirium for 16 days on the inpatient unit, the patient was started on risperidone per a delirium treatment protocol. After the patient began the low-dose risperidone regimen, delirium symptoms improved rapidly. Improvement was noted both in behavior and cognition by day 3 and continued through day 6. Functional status improved significantly. Based on chronology of events and rapid response within 48 hours of institution of treatment with an atypical antipsychotic, risperidone, it appears that risperidone may have exerted some specific effects to improve the mental status. Likely explanation could be the rebalancing of dopaminergic and cholinergic neurotransmitter systems due to D2 receptor blockage by risperidone.

While lithium may have precipitated the episode of delirium, persistence of delirium may be related to the previous TBI. Traumatic brain injury is associated with decreased cholinergic activity.13 Increased dopaminergic activity may result from reduced cholinergic activity, conceptualized as an imbalance of the activities of dopamine and acetylcholine relative to each other.14 Further, antagonism of D2 receptors by risperidone may have been a significant factor in improving delirium symptoms in our patient. The patient was on quetiapine (with low affinity for D2 receptors) at the time he developed delirium, and he continued to receive it while other possible contributory factors for delirium were corrected. Although quetiapine was not helpful in our patient, it has been found useful in lower doses in delirium.15

While we would need a placebo-controlled trial to establish the causal role of risperidone in the improvement of the patient’s symptoms, the temporal association and rapidity of improvement suggests a possible role for risperidone in improvement of persistent delirium. Risperidone also has been reported to be effective in the general treatment of delirium.16 Recently, a similar improvement in cognition during risperidone treatment was reported in a naturalistic study of elderly patients with delirium.17

Antipsychotic medications are used in the treatment of delirium for a relatively brief period. A recent report summarizing the results of a survey from experts recommended treatment with an antipsychotic agent for 1 week.18 Our patient, however, continued to receive risperidone after resolution of delirium as an adjunctive agent to treat his mania and behavioral symptoms associated with dementia.

Conclusions

Our case study suggests that risperidone may provide a rapid and effective treatment of persistent delirium superimposed on dementia. It also suggests that atypical antipsychotics, such as risperidone, may offer an advantage in some cases of delirium compared to other atypical antipsychotics, due to its greater affinity for antagonism of D2 receptors. Additionally, risperidone might help lower the risk of lasting cognitive sequelae of persistent delirium in patients with preexisting cognitive impairment. Further research in pharmacological management of delirium in a homogenous group of delirium patients may be useful in establishing the effectiveness of D2 antagonism.