Effect of Introduction of Elastic Compression Bandages on Quality of Life in Patients With Lower Extremity Vascular Skin Ulcers: A Prospective Study Correlating WOUND-Q Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Evidence-Based Medicine

© 2024 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

Background. Evidence-based medicine and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are helpful tools in the wound care field, but few studies correlating quality of life (QoL) changes with objective changes exist. Objective. To investigate the QoL changes following the shift from primary dressings alone to elastic compression bandages in patients with a new diagnosis of vascular skin ulcer, and to evaluate a possible correlation between objective and subjective changes. Materials and Methods. This study included 122 patients with a new diagnosis of vascular skin ulcer, who had previously used only primary dressings alone. The WOUND-Q was administered at time 0, and after 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months of appropriate compression bandage use. Standardized photographs were taken at the first visit. Group 1 consisted of 51 patients (vascular ulcers of mixed origin), group 2 had 31 patients (arterial origin), and group 3 had 40 patients (venous origin). Software was used for statistical analysis. Results. The ulcer areas decreased by a mean (standard deviation [SD]) of 4.47 (1.76) cm2, 4.06 (0.73) cm2, and 5.04 (0.34) cm2 for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, to a mean (SD) area of 3.19 (2.94) cm2, 2.23 (1.78) cm2, and 4.79 (2.56) cm2, respectively, at 12 months. Almost all WOUND-Q values tended to improve over time for the drainage, smell, and life impact scales. The Spearman correlation coefficient r value was 0.3430 for group 1, 0.5893 for group 2, and 0.3959 for group 3 for correlation between the delta of areas and the delta of the life impact. Conclusion. Introducing compression bandages improved QoL of patients with vascular skin ulcers. Drainage and smell tended to improve over a 1-year period following the switch. A correlation was found between improvements in ulcer area reduction and improvement in life impact scale data.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

Background

With a prevalence almost comparable to that of heart failure,1,2 skin ulcers represent a complex and serious health problem worldwide.3 Skin ulcers also represent a significant problem in terms of patient disability and morbidity, as well as health care costs. Among the most common skin ulcers are those of vascular origin (venous, arterial, or mixed).3-5 Chronic leg ulcers affect approximately 1% of the adult population in high-income countries.6–9

Because vascular skin ulcers represent only the soft tissue manifestation of an underlying pathological vascular condition,10 in most cases, by adequately treating the vascular pathology, visible results can be obtained, even within a few months.11 Despite this, the treatment approach for patients with vascular ulcers is not univocal and simple; rather, it is complex and patient-specific, according to the origin of the problem.12,13 A correct approach should be based on the expertise of a multidisciplinary team that includes a plastic surgeon, wound specialist nurse, vascular surgeon, infectious diseases specialist, geriatrician, and others.13-17

An initial treatment approach should aim to identify the vascular cause in order to provide specific and adequate treatment for the patient’s problem. Computed tomography angiography and Doppler ultrasound play a primary role in the diagnosis of vascular conditions.18,19 Not all chronic skin wounds can achieve complete healing; in such cases, the aims of treatment include halting lesion progression and controlling pain, odor, and local bacterial load.19-22 Thus, plastic surgery may assume a palliative role for the patient’s condition.23 Treatment represents a considerable practical challenge for health care personnel, especially for the plastic surgeon, who often attempts to treat complex wounds that are not responsive to primary dressings such as fat gauze, sterile gauze, and ointment.24 The effect of vascular skin ulcers on patient QoL is extremely negative, both from an economic and a social point of view.24-27

Over the last few years, the medical world has been increasingly recognizing the importance of the patient’s opinion regarding the different types of treatments to which they may be subjected over a prolonged period of time.28 These subjective opinions may represent a key element in the evaluation of the safety and efficacy of the treatment provided.29 PROMs questionnaires allow the collection of information related to patients’ symptoms, QoL, and functional and psychological state.29-31 The information collected allows health care personnel to evaluate the aspects of human life that are difficult to evaluate objectively.32,33

Despite the growing importance of PROMs,34 medical care must be supported by evidence.35 Evidence-based medicine and PROMs are both useful in patient care. Both are helpful in providing the patient the best possible treatment. Among the most used validated questionnaires based on PROMs, which allow clinicians to evaluate changes in perceptions of QoL of patients with ulcers, is the WOUND-Q. This scientifically validated multidimensional questionnaire is beneficial in describing the QoL of patients with any type of wound, independent of anatomic location, and it is suitable for clinical trials, economic evaluations, and clinical practice.35-40

There are few published studies evaluating both QoL changes and centimetric changes in patients with vascular skin ulcers. For this reason, this prospective experimental study had 3 aims. The primary aim was to investigate how QoL changed according to the opinion of the patients with vascular skin ulcers at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months following the change from primary dressings alone to elastic compression bandages, prescribed following the guidelines.41-43 The secondary aim was to understand patients’ perception of the transition from the primary dressings alone to the compression bandages, analyzing their own opinions and evaluating any changes over time. The tertiary goal was to evaluate a possible correlation between objective clinical centimetric variations and subjective PROMs-based changes.

Materials and Methods

A total of 174 patients consecutively referred to the wound care unit at Campus Bio-medico University Hospital of Rome, Italy, with a new diagnosis of vascular skin ulcer (according to computed tomography angiography or Doppler ultrasound) were enrolled in this prospective study. None of these patients had been to a wound care unit previously. They previously had been treated using primary dressings only, such as sterile gauzes, antiseptics, ointments, and greasy gauzes, but never with compression bandages. The exclusion criteria consisted of mental incompetence; uncompensated diseases, excluding vascular conditions (eg, uncompensated diabetes mellitus); prior treatment with compression bandages; failure to complete at least 1 administered test; immunological diseases; other skin conditions; and failure to follow the instructions of the wound care unit medical staff. These exclusion criteria were used to avoid selection and data interpretation bias.

Each patient included in this study, after receiving a correct diagnosis of vascular skin ulcer, received a visit from a plastic surgeon, a wound specialist nurse, and an infectious diseases specialist from the wound care unit. A thorough history was conducted to collect information about the skin ulcer and the patient’s general well-being. As per guidelines,42,43 blood tests were performed to assess any electrolyte or protein imbalances, and a wound culture was performed as necessary.

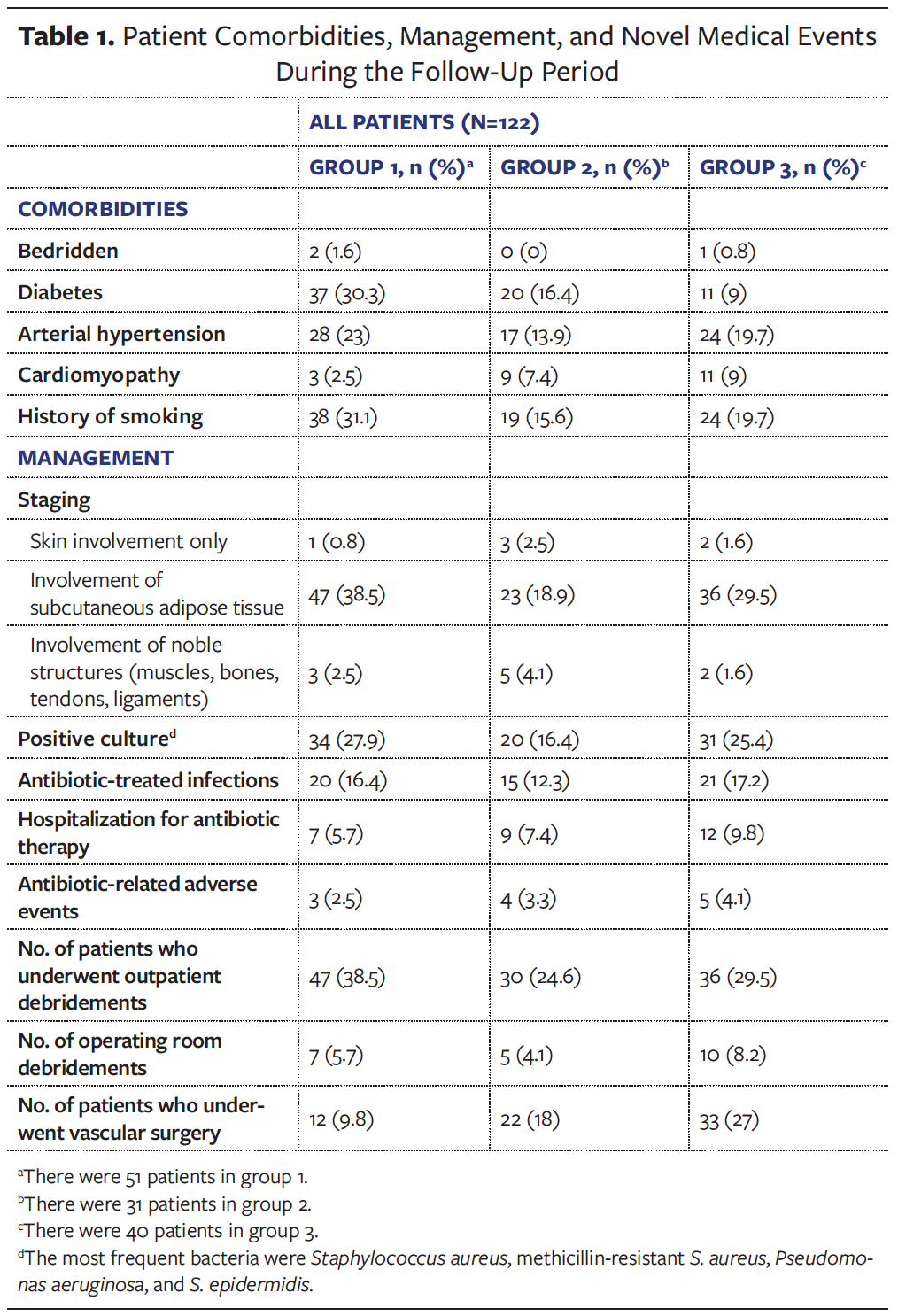

A specific antibiotic therapy was prescribed by the infectious diseases specialist only in selected cases. Surgical debridements were performed either on an outpatient basis or with hospitalization, depending on the ulcer and the patient’s general condition. During the follow-up period, some patients underwent vascular surgery (bypass or stent placement) as indicated by the vascular surgeon. All these data are presented in Table 1.

On the first visit (t0), a standardized photograph of the patient’s main limb lesion was taken with a centimeter reference placed next to the wound. The photographs were then imported into a software program (ImageJ) that allowed measurement of the lesion area by conversion of a pixel scale to a centimeter scale (Figures 1, 2, and 3).

The authors of the current manuscript decided to measure the area only as a physical parameter based on the belief that, unlike pressure ulcers, in vascular ulcers the extension can be considered a more impactful parameter than the depth. All standardized photographs were taken by the same plastic surgeon (C.M.). Each time these data were gathered, they were all exported into a database in Prism 9 (GraphPad), the software used for descriptive statistical analysis.

At t0, the authors prescribed the shift from primary dressings alone to elastic compression bandages according to guidelines.42 For all patients, in case of eschar or slough, debridement was performed first using either Purilon hydrogel (Coloplast), which is made of purified water, sodium carboxymethylcellulose, and calcium alginate, or Iruxol ointment (Smith & Nephew), which is a mixture of collagenase plus chloramphenicol, and then, if necessary, surgically. Each wound was cleansed with hydrogen peroxide, which kills pathogens through oxidation burst and local oxygen production,44,45 and saline. In case of exudation, polyurethane foams and sterile gauzes were placed in situ.46,47 Bandaging was performed with elastic gauzes with different compression starting from the root of the toes and proceeding to the calf (3 cm below the popliteal cord), and including the heel. For ulcers of mixed etiology, a reduced level of compression was used (23 mm Hg to 30 mm Hg at the ankle), for venous ulcers a high level of compression was chosen (30 mm Hg to 40 mm Hg at the ankle),42 and for arterial ulcers an extremely light, nonocclusive bandage (Idealflex line; Farmac-Zabban) was used, aimed mostly at keeping the underlying gauzes or polyurethane foams in place.43 Following the guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum,42 great consideration was given to the ankle-brachial index at each follow-up visit in order to initially decide the degree of bandage compression or to decide whether further treatments were warranted.

Of the initial 174 patients, only 122 were included in the final sample. Forty-eight patients were excluded due to lack of follow-up, 3 died, and 1 was diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. Because only 3 types of treatment were used, according to the etiology of the lesion, the study patients were divided into 3 groups: group 1 consisted of 51 patients with vascular ulcers of mixed origin, group 2 consisted of 31 patients with vascular ulcers of arterial origin, and group 3 consisted of 40 patients with vascular ulcers of venous origin. Figure 4 shows the patients’ enrollment process. A scientifically validated multidimensional questionnaire (WOUND-Q) was administered to all patients just after the first medical management (t0), and then at 1 month (t1), 6 months (t6), and 12 months (t12) after application of the first compression bandage. Ulcer measurements were also taken at time 0 (t0) and at t12.

Three particular scales within the multidimensional questionnaire were selected to assess QoL (drainage, smell, and life impact), and 1 specific scale was used to evaluate the new type of treatment (dressing). The WOUND-Q was administered in paper form in a calm environment after the visit, so that the patient would not be affected by outside influences. No electronic laboratory notebook was used. To ensure patient anonymity to the extent possible, each patient was given a code known only to a physician outside of the wound care unit, who was responsible for exporting this data to the software used for statistical analysis. Each patient signed a written consent form and was aware of this clinical investigation.

Each of the WOUND-Q scales analyzed consisted of a pool of questions that allowed assessment of PROMs in that specific area of interest. The drainage scale focuses on how much the fluids emitted from the skin lesion in the last week affected the patient’s QoL by allowing assessment of color, thickness, odor, notability, interference with the ability to enjoy life, amount of exudate, and other factors. The smell scale is specific to assessing how the bad odor emitted from the wound negatively affects QoL. The life impact scale allows for a global assessment of QoL evaluation in relation to the patient’s feelings about the ulcer, while the dressing scale permits description of the subjective feelings that the patients experienced with the dressings used.

Each question was scored from 1 (most negative value) to 4 (most positive value). The sum of the scores for each group of questions (scale) per individual patient was converted using a conversion Rasch scale table provided by the Q-Portfolio team (Techna Institute).48 This permitted the linearization of the ranges of values into a score from 0 (worst) to 100 (best).49 The Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to assess whether the distribution of values was gaussian/normal. A descriptive analysis of the values was performed, and then the Friedman test was used. This nonparametric test is useful for comparing 3 or more paired groups. Because the Friedman test only allowed assessment of whether there was a minimum of 1 statistically significant difference P < .05 between the variables analyzed, but did not detect between which sets of variables the difference existed, it was also necessary to use the Dunn post-test for multiple comparisons. This allowed the researchers to identify in which sets of variables analyzed there was a statistically significant difference. For each scale and for each group separately, the presence of statistically significant differences between t0 and t1, between t1 and t6, and between t6 and t12 was assessed. A possible correlation between the deltas of the WOUND-Q life impact (time 0–time 12) and the deltas of the areas (time 0–time 12) for each group was finally evaluated using the Spearman test. Figure 5 summarizes the data collection and statistical analysis processes.

Because the goal was not to compare the values between the 3 groups, but to evaluate the trend in values individually within each group over time, it was not necessary to include control groups. Patients’ sociodemographic characteristics (Table 2) and medical characteristics and events during the follow-up period were also noted.

The study was conducted in accordance with local regulations, international standards of the European Union Good Practice Directive,50 and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study followed the STROBE statement (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology).51

Results

Sociodemographic analysis

Data regarding sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, BMI, marital status, education level, employment status, and income status) are shown in Table 2. Of the 122 patients studied, 55.7% had diabetes, 56.6% had hypertension, and 66.4% had a history of smoking. The majority of patients (86.9%) had a vascular skin wound involving the subcutaneous adipose tissue layer. Information about wound location, bacterial infections, hospitalization, antibiotic therapy, debridement, and surgeries are reported in Tables 1 and 3. In group 1, the majority of patients reported a skin ulcer duration of 8 months to 11 months, whereas in groups 2 and 3 the majority of patients had skin ulcer duration of 5 months to 7 months (Table 3).

Wound area clinical results

Analysis of the ulcer area using ImageJ software showed a mean (SD) area at time 0 of 7.66 (3.30) cm² for group 1, 6.29 (1.52) cm² for group 2, and 9.83 (2.42) cm² for group 3. From time 0 to time 12 the ulcer area decreased by a mean (SD) of 4.47 (1.76) cm2, 4.06 (0.73) cm2, and 5.04 (0.34) cm2 for groups 1, 2, and 3, respectively, with a respective final mean (SD) area of 3.19 (2.94) cm2, 2.23 (1.78) cm2, and 4.79 (2.56) cm2 at 12 months after the switch from primary dressings alone to elastic compression bandaging. More information is reported in Table 3.

WOUND-Q results

The WOUND-Q mean values converted to Rasch scale scores are organized by groups, scale, and time in Table 4. At time 0, the questionnaire assessed patient opinion on primary dressings performed up to the week before, whereas it was at time 1 that the first questionnaire assessment of patient opinion regarding compression bandages and resultant changes in QoL occurred. For the drainage scale, the Friedman test with Dunn post-test for multiple comparisons showed statistically significant (P < .05) differences between time 0 and time 1 and between time 1 and time 6 in group 1 and group 3, and between time 0 and time 1 in group 2 (Table 5). Regarding the smell scale, the same test allowed detection of an individual statistically significant difference between time 0 and time 1 for all 3 groups (P < .05). For the life impact scale, a statistically significant improvement between time 0 and time 1 was found for all 3 groups (P < .05). The Friedman test with Dunn post-test for multiple comparisons showed a significant deterioration of values between time 0 and time 1 for groups 1 and 2 on the dressing scale (P < .05). This initial decreasing trend was also observed in group 3, although this was not statistically significant (P > .05). In contrast, the values significantly increased between time 1 and time 6 for all 3 groups (P < .05), and they increased (but not significantly) between time 6 and time 12. Table 5 details the results of the Friedman test with Dunn post-test for multiple comparisons. In general, almost all WOUND-Q values tended to improve over time for the drainage, smell, and life impact scales (Table 4).

After calculating the delta of areas (time 0–time 12) and delta of Rasch values of the life impact scale for each individual group, the existence or nonexistence of a possible statistical correlation using the Spearman test was evaluated. A statistically significant correlation was found between the delta of areas between time 0 and time 12 and the delta of Rasch values of the life impact scale for all groups. The Spearman test showed an r value of 0.3430 for group 1, 0.5893 for group 2, and 0.3959 for group 3.

Discussion

Vascular skin ulcers of the lower limb are debilitating and extremely painful conditions that adversely affect patients’ QoL and their relational and social capacity. Because vascular ulcers are only a cutaneous manifestation of an underlying condition, treating vascular pathology has a very important role in the overall treatment approach.

PROMs can express in detail patients’ experiences regarding the treatment used and their QoL. Analysis of these data, which objectively translate what is actually subjective, is extremely useful when combined with scientific analysis of wound improvements for better understanding whether a type of treatment is working. In this way, these questionnaires allow health care personnel to better understand the degree of patient distress and therefore are useful, for example, in understanding whether a compression bandage is too tight or not. Specifically, clinical indications for the degree of compression bandage pressure are reported in the literature, and objective signs such as edema and signs of skin distress should guide the health care provider; from a modern medicine perspective, PROMs represent an additional source of information that can help the health care provider empathize even more with the patient and better appreciate their needs. The use of PROMs-based questionnaires as a means of evaluating treatments remains controversial, however, because the same questionnaire can lead to markedly different results depending on a patient’s culture, habits, nationality, and lifestyle.52-55 Correlation with objective data and their variations is therefore necessary in modern medicine.50-52

In the current study, the results obtained from the administration of the WOUND-Q showed that proper treatment of vascular ulcers of the lower extremities, using appropriate elastic compression bandages, may lead to a significant improvement in patients’ QoL. This is especially evident in the first month after the shift from primary dressings alone to compression bandages. There are numerous factors that lead the authors of the current study to assume that these improvements are strongly attributable to the compression bandages. For example, exudate can form in the context of a vascular ulcer, especially one with a venous etiology, and a dressing that applies the correct pressure can reduce the stagnation of exuded fluids in the interstitium by preventing the pathogenetic mechanism that leads to exudate formation.56,57 Regarding smell scale scores, the authors of the current study believe that improvements may be mainly attributable to how patients are followed up in the wound care unit, in terms of frequency of dressing changes, performance of culturally sensitive examination, antibiotic therapy, and other factors.58 Data on wound management are shown in Table 1. It can also be assumed that the various layers of the compression bandage, although breathable, may contribute to odor control compared with the previous individual applications of primary dressings. It may be further supposed that the improvements obtained for both scales may also be partly related to the vascular treatments performed on some patients, especially in the period between t1 and t6.59 The drainage and smell scales could be considered indirect indicators of a patient’s QoL.

In contrast to the drainage and smell scales, the life impact scale can be considered a more direct and comprehensive assessment of these patients’ QoL. As noted above, according to analysis with the Friedman test with Dunn post-test for multiple comparisons, QoL significantly improved between time 0 and time 1 in all 3 groups. It continued to improve, although not significantly, between time 1 and time 6 and between time 6 and time 12. Thus, the shift from treatment with primary dressing alone to elastic compression bandaging improved the QoL of patients with lower extremity vascular ulcers.

Evaluation by the patients themselves regarding the type of dressing is of utmost importance. Health care personnel can only imagine how bulky, visible, and irritating to wear these compression dressings are, especially in summer, and patients may not be enticed to make this shift. This statement is easily backed up by the study authors’ experience in clinical practice, as well as by the results that emerged from the administration of the WOUND-Q in the current study.

Initially, in the dressing scale, between t0 and t1 mean values tended to decrease for all groups (significantly for group 1 and group 2, and nonsignificantly for group 3). The lower the value, the worse the outcome. This means that patients who were treated with compression bandages initially evaluated their experience with this new type of dressing negatively. However, after a short time the values tended to rise again, which means that patients got used to the new dressing (compression bandage). The data are important and useful for patient education, especially in cases in which patients with newly diagnosed vascular ulcers do not wish to be treated with compression bandages based on a sense of shame or the possibility of discomfort. The physician cannot rely solely on PROMs in a decision-making algorithm60; thus, it was necessary to determine whether there was any correlation with objective data and their variations. As noted above, the current study analysis revealed a statistically significant correlation between the delta of areas between time 0 and time 12 and the delta of Rasch values of the life impact scale for all groups, with a Spearman correlation coefficient r value of 0.3430 for group 1, 0.5893 for group 2, and 0.3959 for group 3. Thus, it can also be stated that the improvements observed over 1 year of compression bandage treatment positively correlated with a decrease in area of the lower limb vascular ulcers.

Strengths of the study include using a standardized methodology in the patient approach, following the same patients over a 1-year follow-up period, using an internationally validated questionnaire (WOUND-Q), and stratifying the sample according to vascular etiology of the lesions.

Limitations

This study has limitations, including the single-center setting and the small size of the study sample. Limitations also include the study design—that is, a low-level, non-randomized observational study based on PROMs. As noted above, PROMs scores may vary depending on the country in which the questionnaire is administered.52 Multicenter studies with a larger sample size and longer follow-up time are needed.

Conclusion

Introducing elastic compression bandages improves the QoL of patients with vascular skin ulcers, whether the ulcers are arterial, venous, or mixed. Additionally, drainage and smell tend to improve over a period of 1 year after the switch to elastic compression bandages. The current study found a statistical correlation between improvements in ulcer area reduction over 1 year, and improvement in WOUND-Q life impact scale data. The WOUND-Q has proven to be a tool of paramount importance in the modern wound care field.

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Marco Gratteri, MD, MSc1; Giovanni Francesco Marangi, MD, PhD1; Carlo Mirra, MD1; Annalisa Cogliandro, MD, PhD1; Barbara Cagli, MD, PhD1; Francesco Segreto, MD, PhD1; Pier Camillo Parodi, MD, PhD2; Anna Scarabosio, MD2; Luca Savani, MD1; and Paolo Persichetti, MD, PhD1

Affiliations: 1Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, Italy; 2Clinic of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Academic Hospital of Udine, Department of Medical Area (DAME), University of Udine, Udine, Italy

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: The study was conducted in accordance with local regulations, international standards of Good Clinical Practice, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed an informed consent.

Correspondence: Carlo Mirra, MD; Department of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery, Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Via Alvaro del Portillo 200, Rome 00128, Italy; carlo.mirra93@gmail.com

Manuscript Accepted: September 20, 2024

Recommended Citation

Gratteri M, Marangi GF, Mirra C, et al. Effect of introduction of elastic compression bandages on quality of life in patients with lower extremity vascular skin ulcers: a prospective study correlating WOUND-Q patient-reported outcome measures and evidence-based medicine. Wounds. 2024;36(12):419-428. doi:10.25270/wnds/24066

References

1. Berry C, Murdoch DR, McMurray JJ. Economics of chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001;3(3):283-291. doi:10.1016/s1388-9842(01)00123-4

2. Fife CE, Carter MJ. Wound care outcomes and associated cost among patients treated in US outpatient wound centers: data from the US Wound Registry. Wounds. 2012;24(1):10-17.

3. Li WW, Carter MJ, Mashiach E, Guthrie SD. Vascular assessment of wound healing: a clinical review. Int Wound J. 2017;14(3):460-469. doi:10.1111/iwj.12622

4. Bluestein D, Javaheri A. Pressure ulcers: prevention, evaluation, and management. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(10):1186-1194.

5. Markova A, Mostow EN. US skin disease assessment: ulcer and wound care. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):107-111, ix. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.08.005

6. Gottrup F, Apelqvist J, Bjarnsholt T, et al. EWMA document: antimicrobials and non-healing wounds. Evidence, controversies and suggestions. J Wound Care. 2013;22(5 Suppl):S1-89. doi:10.12968/jowc.2013.22.Sup5.S1

7. Margolis DJ, Bilker W, Santanna J, Baumgarten M. Venous leg ulcer: incidence and prevalence in the elderly. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(3):381-386. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.121739

8. Baker SR, Stacey MC, Jopp-McKay AG, Hoskin SE, Thompson PJ. Epidemiology of chronic venous ulcers. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):864-867. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800780729

9. Probst S, Saini C, Gschwind G, et al. Prevalence and incidence of venous leg ulcers—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2023;20(9):3906-3921. doi:10.1111/iwj.14272

10. Hofmann AG, Deinsberger J, Oszwald A, Weber B. The histopathology of leg ulcers. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2024;11(1):62-78. doi:10.3390/dermatopathology11010007

11. Powers JG, Higham C, Broussard K, Phillips TJ. Wound healing and treating wounds: Chronic wound care and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(4):607-625; quiz 625-626. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.08.070

12. Ballard K, Baxter H. Developments in wound care for difficult to manage wounds. Br J Nurs. 2000;9(7):405-408, 410, 412. doi:10.12968/bjon.2000.9.7.6319

13. Segreto F, Carotti S, Marangi GF, et al. The use of acellular porcine dermis, hyaluronic acid and polynucleotides in the treatment of cutaneous ulcers: single blind randomised clinical trial. Int Wound J. 2020;17(6):1702-1708. doi:10.1111/iwj.13454

14. Cutting KF, White R. Defined and refined: criteria for identifying wound infection revisited. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9(3):S6-15. doi:10.12968/bjcn.2004.9.Sup1.12495

15. Mervis JS, Phillips TJ. Pressure ulcers: pathophysiology, epidemiology, risk factors, and presentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(4):881-890. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.069

16. Stephen-Haynes J. The world of wound care. Br J Nurs. 2017;26(15):S3. doi:10.12968/bjon.2017.26.15.S3

17. Segreto F, Marangi GF, Nobile C, et al. Use of platelet-rich plasma and modified nanofat grafting in infected ulcers: Technical refinements to improve regenerative and antimicrobial potential. Arch Plast Surg. 2020;47(3):217-222. doi:10.5999/aps.2019.01571

18. Dyet JF, Nicholson AA, Ettles DF. Vascular imaging and intervention in peripheral arteries in the diabetic patient. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2000;16 Suppl 1:S16-22. doi:10.1002/1520-7560(200009/10)16:1+<::aid-dmrr131>3.0.co;2-w

19. Apelqvist J a. P, Lepäntalo MJA. The ulcerated leg: when to revascularize. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2012;28 Suppl 1:30-35. doi:10.1002/dmrr.2259

20. Harriott MM, Bhindi N, Kassis S, et al. Comparative antimicrobial activity of commercial wound care solutions on bacterial and fungal biofilms. Ann Plast Surg. 2019;83(4):404-410. doi:10.1097/SAP.0000000000001996

21. Chaudhry S, Lee K. Diagnosing and managing venous stasis disease and leg ulcers. Clin Geriatr Med. 2024;40(1):75-90. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2023.09.004

22. Stephens M, Chester-Bessell D, Rose S. Wound care in hard-to-reach populations: rough sleepers. Br J Nurs. 2024;33(4):S34-S37. doi:10.12968/bjon.2024.33.4.S34

23. Woo KY, Krasner DL, Kennedy B, Wardle D, Moir O. Palliative wound care management strategies for palliative patients and their circles of care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2015;28(3):130-140; quiz 140-142. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000461116.13218.43

24. Marangi GF, Segreto F, Morelli Coppola M, Arcari L, Gratteri M, Persichetti P. Management of chronic seromas: a novel surgical approach with the use of vacuum assisted closure therapy. Int Wound J. 2020;17(5):1153-1158. doi:10.1111/iwj.13447

25. Drew P, Posnett J, Rusling L, Wound Care Audit Team. The cost of wound care for a local population in England. Int Wound J. 2007;4(2):149-155. doi:10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00337.x

26. Al-Gharibi KA, Sharstha S, Al-Faras MA. Cost-effectiveness of wound care: a concept analysis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2018;18(4):e433-e439. doi:10.18295/squmj.2018.18.04.002

27. Carter MJ. Cost-effectiveness research in wound care: definitions, approaches, and limitations. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2010;56(11):48-59.

28. Bonnet E, Maulin L, Senneville E, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for infectious disease management of diabetic foot infection (DFI) - 2023 SPILF. Infect Dis Now. 2024;54(1):104832. doi:10.1016/j.idnow.2023.104832

29. Marangi GF, Mirra C, Gratteri M, et al. Switching from galenic to advanced dressings or vacuum assisted closure therapy can improve quality of life of patients with chronic non-responsive pressure skin ulcers: preliminary data with Italian translation of WOUND-Q. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2024;13(3):131-139. doi:10.1089/wound.2022.0150

30. Scholten AC, Haagsma JA, Steyerberg EW, van Beeck EF, Polinder S. Assessment of pre-injury health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15(1):10. doi:10.1186/s12963-017-0127-3

31. Yan R, Yu F, Strandlund K, Han J, Lei N, Song Y. Analyzing factors affecting quality of life in patients hospitalized with chronic wound. Wound Repair Regen. 2021;29(1):70-78. doi:10.1111/wrr.12870

32. Vogt TN, Koller FJ, Santos PND, Lenhani BE, Guimarães PRB, Kalinke LP. Quality of life assessment in chronic wound patients using the Wound-QoL and FLQA-Wk instruments. Invest Educ Enferm. 2020;38(3):e11. doi:10.17533/udea.iee.v38n3e11

33. Teare J, Barrett C. Using quality of life assessment in wound care. Nurs Stand. 2002;17(6):59-60, 64, 67-68.

34. Savadkoohi H, Barasteh S, Ebadi A, et al. Psychometric properties of Persian version of wound-QOL questionnaire among older adults suffering from chronic wounds. Front Psychol. 2022;13:1041754. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1041754

35. Lentsck MH, Baratieri T, Trincaus MR, Mattei AP, Miyahara CTS. Quality of life related to clinical aspects in people with chronic wound. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2018;52:e03384. doi:10.1590/S1980-220X2017004003384

36. Conde Montero E, Sommer R, Augustin M, et al. Validation of the Spanish Wound-QoL Questionnaire. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 2021;112(1):44-51. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2020.09.007

37. Sommer R, Hampel-Kalthoff C, Kalthoff B, et al. Differences between patient- and proxy-reported HRQoL using the Wound-QoL. Wound Repair Regen. 2018;26(3):293-296. doi:10.1111/wrr.12662

38. Klassen AF, van Haren ELWG, van Alphen TC, et al. International study to develop the WOUND-Q patient-reported outcome measure for all types of chronic wounds. Int Wound J. 2021;18(4):487-509. doi:10.1111/iwj.13549

39. van Alphen TC, Poulsen L, van Haren ELWG, et al. Danish and Dutch linguistic validation and cultural adaptation of the WOUND-Q, a PROM for chronic wounds. Eur J Plast Surg. 2019;42(5):495-504. doi:10.1007/s00238-019-01529-7

40. Tolbert E, Brundage M, Bantug E, et al. Picture this: presenting longitudinal patient-reported outcome research study results to patients. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(8):994-1005. doi:10.1177/0272989X18791177

41. Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, Abdul Nazir CP. Patient-reported outcomes: a new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res. 2011;2(4):137-144. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.86879

42. O’Donnell TF, Passman MA, Marston WA, et al. Management of venous leg ulcers: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery® and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(2 Suppl):3S-59S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.049

43. Bonham PA, Flemister BG, Droste LR, et al. 2014 Guideline for management of wounds in patients with lower-extremity arterial disease (LEAD): an executive summary. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2016;43(1):23-31. doi:10.1097/WON.0000000000000193

44. Rai S, Gupta TP, Shaki O, Kale A. Hydrogen peroxide: its use in an extensive acute wound to promote wound granulation and infection control - is it better than normal saline? Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2023;22(3):563-577. doi:10.1177/15347346211032555

45. Kanta J. The role of hydrogen peroxide and other reactive oxygen species in wound healing. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2011;54(3):97-101. doi:10.14712/18059694.2016.28

46. Queen D, Orsted H, Sanada H, Sussman G. A dressing history. Int Wound J. 2004;1(1):59-77. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4801.2004.0009.x

47. May A, Kopecki Z, Carney B, Cowin A. Antimicrobial silver dressings: a review of emerging issues for modern wound care. ANZ J Surg. 2022;92(3):379-384. doi:10.1111/ans.17382

48. McClimans L, Browne J, Cano S. Clinical outcome measurement: models, theory, psychometrics and practice. Stud Hist Philos Sci. 2017;65-66:67-73. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2017.06.004

49. WOUND-Q-USERS-GUIDE.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2024. https://qportfolio.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/WOUND-Q-USERS-GUIDE.pdf

50. The European Union Good Clinical Practice Directive. The Embassy of Good Science. May 9, 2023. Accessed December 5, 2024. https://embassy.science:443/wiki/Resource:9984ebbc-f292-4b62-8c85-754cad2ce748

51. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-349. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

52. Moss TP, Cogliandro A, Pennacchini M, Tambone V, Persichetti P. Appearance distress and dysfunction in the elderly: international contrasts across Italy and the UK using DAS59. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013;37(6):1187-1193. doi:10.1007/s00266-013-0209-y

53. Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):415-423. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

54. Freddi G, Romàn-Pumar JL. Evidence-based medicine: what it can and cannot do. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2011;47(1):22-25. doi:10.4415/ANN_11_01_06

55. Rohrich RJ, Cohen JM, Savetsky IL, Avashia YJ, Chung KC. Evidence-based medicine in plastic surgery: from then to now. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148(4):645e-649e. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000008368

56. Coleridge-Smith PD. Leg ulcer treatment. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49(3):804-808. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.01.003

57. Mansilha A, Sousa J. Pathophysiological mechanisms of chronic venous disease and implications for venoactive drug therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(6):1669. doi:10.3390/ijms19061669

58. Gupta S, Andersen C, Black J, et al. Management of chronic wounds: diagnosis, preparation, treatment, and follow-up. Wounds. 2017;29(9):S19-S36.

59. Kerstein MD. The non-healing leg ulcer: peripheral vascular disease, chronic venous insufficiency, and ischemic vasculitis. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1996;42(10A Suppl):19S-35S.

60. Benbow M. Quality of life is starting to take precedence. Br J Nurs. 2009;18(15):S3. doi:10.12968/bjon.2009.18.sup5.43567