Cutaneous Metastases Mimicking Hidradenitis Suppurativa: A Diagnostic Challenge

©2025 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of Wounds or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates

Abstract

Background. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, recurrent, and debilitating inflammatory condition characterized by abscesses, comedones, and nodules. The heterogeneous presentation of HS often leads to diagnostic challenges, with clinical mimics such as cutaneous metastases (CMs) being of particular importance. CMs can present as initial manifestations of metastatic disease, necessitating accurate identification to guide potentially lifesaving treatment. However, the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for HS and CMs differ significantly, underscoring the need for prompt and accurate differentiation. Case Report. This report presents 3 cases of primary malignancies in which CMs mimicked HS. Case 1 had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; case 2 had a history of right breast atypical ductal hyperplasia and borderline low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, along with triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast with extensive metastasis to the iliac bone and lung; and case 3 had invasive mammary carcinoma of the right breast with axillary lymph node involvement. All 3 patients presented with nodular lesions resembling HS, but further investigation, including molecular testing, confirmed the diagnosis of CMs. Conclusion. The clinical overlap between HS and CMs, which can present with similar features such as nodules, abscesses, and draining lesions, underscores the critical importance of distinguishing these entities. Despite their similar clinical appearance, HS and CMs have vastly different management protocols. Accurate diagnosis of CMs enables timely and appropriate intervention, which in turn aids in optimizing clinical outcomes and ensuring the use of effective treatment strategies for affected patients.

Abbreviations: CM, cutaneous metastases; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; GATA3, GATA binding protein 3; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa.

Background

CMs originate from internal and hematological malignancies that disseminate to the skin. CMs originating from internal malignancies occur in only 0.7% to 10% of all reported cases and are typically indicative of poor prognosis.1 Common locations for metastasis include the head and neck, trunk, upper extremities, and lower extremities.1,2 These lesions exhibit a broad array of clinical morphologies ranging from erythematous nodules or papules to ulcers, plaques, and diffuse sclerodermoid involvement.2 While CMs are often diagnosed after the identification of a primary internal or hematological malignancy, in some cases cutaneous metastases can be the initial sign of an underlying malignancy, necessitating prompt recognition by physicians. Given their complex clinical presentation, CMs have been found to mimic HS, a chronic, recurrent, and debilitating inflammatory skin disorder commonly affecting the axillary and inguinal skinfolds.1,3

Although HS and CM are similar in their clinical presentations, the diagnostic tests, treatment protocols, and prognosis for them are fundamentally distinct.4-6 Whereas the diagnosis of HS is primarily clinical, diagnosis of CMs requires the use of appropriate molecular and biomolecular techniques.5,6 The treatment of HS is primarily symptomatic, with emphasis placed on pain relief, drainage, and preventing bacterial superinfections.3 Common agents to relieve pain and inflammation include topical corticosteroids and biologics such as triamcinolone, adalimumab, and infliximab.3 These treatment strategies vastly differ from those used to adequately manage cutaneous metastases, which range from cutaneous excision to systemic chemoradiation therapy.5,6 The excision of cutaneous metastases depends on the size, depth, and location of malignant lesions.5

Genetic testing also plays a crucial role in determining adequate management for cutaneous metastases; this is another distinguishing component of the management of CMs vs. HS.5 Furthermore, identifying CMs masquerading as HS is essential for physicians to intervene effectively and direct care appropriately.

This report presents 3 cases of CMs originating from DLBCL and breast cancers that mimicked HS.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 68-year-old male with a history of DLBCL presented to the emergency department with a 1-week history of fever and 2 firm, dark brown nodules in the left axilla, 1 of which was actively draining purulent material upon light manipulation (Figure 1). The patient initially received a 1-week course of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, resulting in temporary improvement. However, symptoms recurred 4 days later, prompting admission for further evaluation. Given the patient’s history of DLBCL and severe presentation, CMs was considered a leading differential diagnosis. While the clinical findings alone were suggestive of active HS or an atypical infectious etiology, the patient’s history raised suspicion for metastatic involvement.

Histopathological analysis revealed a diffuse dermal infiltrate composed of large, atypical cells with slightly irregular nuclear contours, fine chromatin, prominent nucleoli, frequent mitotic figures, and small necrotic foci (Figure 2). Pan culture, H&E staining, and immunohistochemistry confirmed the diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis of DLBCL. The infiltrate demonstrated strong positivity for CD20, CD10, B-cell lymphoma 6 protein, multiple myeloma oncogene 1, cellular myelocytomatosis oncogene, and p53, with a high proliferative index as demonstrated by a high percentage of Ki-67 staining seen on immunohistochemistry (90%, 4+/4). As of this writing, the patient is currently under management by the hematology and oncology team.

Case 2

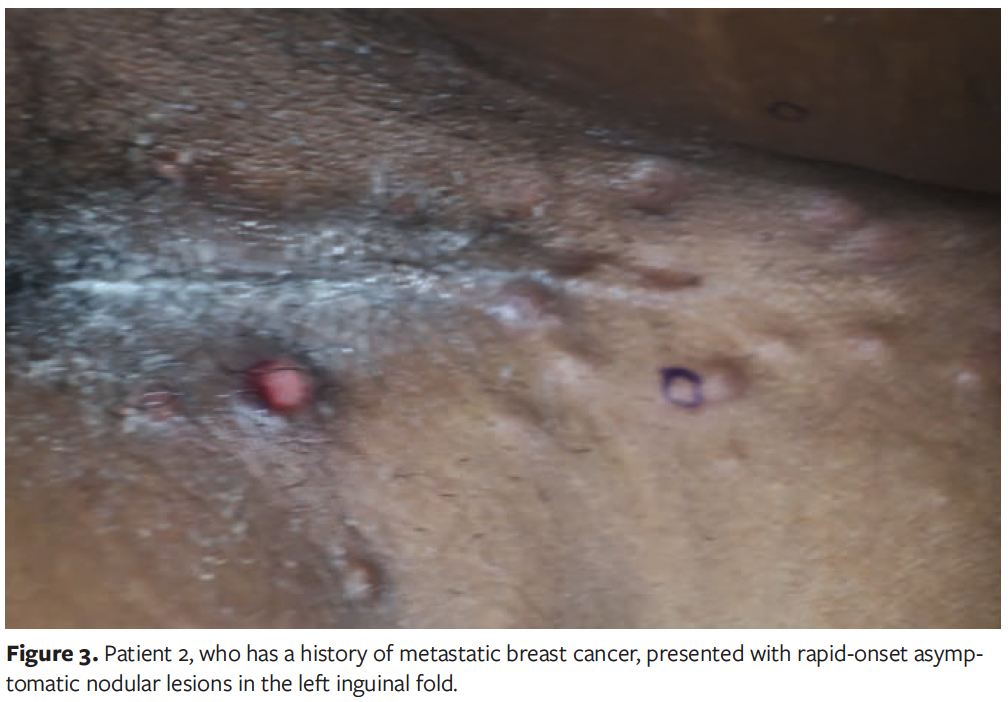

A 51-year-old female with a history of metastatic breast cancer was referred to dermatology for evaluation of asymptomatic nodular lesions in the left inguinal fold that were incidentally discovered during left lower extremity angiography (Figure 3). Her medical history was notable for right breast atypical ductal hyperplasia, borderline low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ, and triple-negative invasive ductal carcinoma of the left breast with extensive metastases to the iliac bone and the lungs. She had previously undergone chemotherapy and prophylactic left mastectomy with reconstructive surgery. In the context of her extensive malignancy history, CMs was considered, and the lesion was biopsied for further evaluation.

Histopathological examination of the biopsied inguinal nodules, supported by immunohistochemistry, revealed tumor cells positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and GATA3 (Figure 4). The morphological features were consistent with invasive ductal carcinoma (Figure 4), confirming a diagnosis of CM secondary to the primary triple-negative breast carcinoma. As of this writing, the patient is receiving hospice care.

Case 3

A 59-year-old female with a history of breast cancer presented with a progressively enlarging, tender nodular lesion in the left axilla over the past 3 months (Figure 5). Her medical history included invasive mammary carcinoma of the right breast with axillary lymph node involvement, which was diagnosed in 2001. In the context of the patient’s malignancy history, the lesion was biopsied with CM as a primary differential diagnosis.

Histopathological examination of a punch biopsy of the axillary cutaneous nodule revealed malignant cells within the dermis that were strongly positive for estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor but negative for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (Figure 6). Immunohistochemistry confirmed positivity for GATA3, mammaglobin, and cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Subsequent left axillary lymph node dissection demonstrated metastatic mammary carcinoma in 3 of 16 lymph nodes, with extra nodal extension measuring up to 14 mm.

These findings led to a diagnosis of metastatic invasive carcinoma with dermal deposits originating from primary breast cancer. As of this writing, the patient remains under oncology management.

Discussion

As noted above, CMs are rare, occurring in up to 10% of patients with systemic primary malignancies.1 The prevalence is on the rise due to the increased number of patients living with malignancies. Identifying CMs is of prime importance because they indicate advancement and/or recurrence of pretreated malignancies; alternatively, in rare cases CMs can be the presenting feature of an occult primary neoplasm.² CMs arising from hematological and internal malignancies may undergo different molecular mechanisms of metastasis, including direct spread, lymphatic seeding, or hematogenous spread, presenting with varied morphologies.5 Inflammatory conditions such as HS are frequently misdiagnosed in scenarios with the presence of internal malignancies.5,6 The current report discusses 3 cases of CMs masquerading as HS.

HS is a multifactorial chronic inflammatory skin condition that is triggered by an interplay between genetic, immune, microbiological, and hormonal factors, culminating in follicular rupture with subsequent perifollicular inflammation propagated by invasion of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes.5-8 Recurrent inflammation and secondary infection induce nodules, abscesses, sinus tracts, fistulas, and scarring.3 HS is clinically defined by the presence of double-ended comedones, abscesses, nodules, sinus tracts, fistulas, scarring, pain, drainage, and malodor manifesting more commonly in the axillary, inguinal, and perineal skin folds.3 HS is usually diagnosed early, around the second decade of life.9 None of the 3 patients in the current case series had a documented history of HS.

CMs originating from both visceral and hematological malignancies present acutely with a spectrum of skin lesions including macules, crusted ulcerated patches, nodules, tumors, telangiectasias, and infiltrated plaques. One study reported that the most frequent manifestations were nodules (61%), followed by tumors (30%) predominantly found on the anterior chest wall, abdominal wall, and neck.10 Lesions that appear along the distribution of HS characteristically lack chronicity and distinctive features of HS such as comedones, sinus tracts, and scarring.6 CMs may present asymptomatically or with pain and tenderness.10 The prognosis of CMs is poor, with median survival of 9 months after initial diagnosis.6 Thus, early diagnosis of CMs is a critical step in directing further life-altering tailoring of treatment. Breast, head and neck, and pancreatic cancer are the most common internal malignancies that give rise to CMs.2,5 Symptomatic or asymptomatic skin nodules are commonly found on the anterior chest wall, abdominal wall, and neck, with surrounding concomitant erythematous to violaceous patches.5,6 Given their diverse clinical presentations, CMs have been found to mimic HS.1,2 However, while CMs frequently present as rapidly evolving skin nodules, HS lesions progress gradually.4,5 The absence of a prior history of HS should serve as a critical clue, prompting a more urgent and thorough evaluation for an associated known or occult primary malignancy. An acutely presenting skin lesion in an area localizing to the local drainage of a known malignancy should raise the possibility of metastatic disease and should mandate biopsy. Whereas the diagnosis of HS is based on clinical evaluation, CMs are diagnosed with skin biopsies that are tested for various molecular markers and H&E staining.3-5 Microscopically, CMs appear as deposits of pleomorphic, dysplastic cancer cells with mitotic figures and AE1/AE3 markers in the dermis.5

Treatment goals for HS are chronic maintenance and wound care with the aim of controlling pain, drainage, and superinfections; such treatment includes topical or oral antibiotic therapy and intralesional corticosteroids or neurotoxins, systemic immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory agents, and surgery.4,11 Treatment for CMs includes tailored symptomatic and wound care in the interim of guideline-directed therapies. CM lesions less than 1 cm in diameter are excised, whereas widespread CMs are treated as per guidelines specific to primary tumor types with systemic chemotherapy, cryotherapy, and laser ablation.5 These drastic differences in the management of HS and CMs mandate prompt recognition and distinction of these 2 cutaneous conditions. Physicians should prioritize incorporating CMs into the differential diagnosis for patients with a personal or family history of cancer who present with rapidly progressive skin lesions resembling those of HS. Being informed of the gamut of clinical presentations of CMs can enable physicians to significantly contribute toward identifying impending life-threatening scenarios and making critical treatment decisions for patients with cancer.

Limitations

The limitations of this study can be attributed to the absence of a diverse range of cancers represented by the patients. These patients had either breast cancer or lymphoma, but a multitude of other hematological and visceral malignancies have also been shown to exhibit other cutaneous conditions such as HS, and these other malignancies were not represented in the current study. The scope of malignancies represented in this study is somewhat limited; thus, it is crucial for physicians to understand that malignancies aside from breast cancer and DLBCL may mimic inflammatory cutaneous conditions such as HS.

Conclusion

CMs mimic inflammatory conditions such as HS. CMs are diagnosed through histopathological examination and molecular biomarkers on biopsied lesions, whereas HS diagnosis relies on clinical assessment. Given the complexities of diagnosing CMs, it is crucial to involve a pathologist with advanced knowledge to ensure the selection of appropriate diagnostic tests, including histopathological evaluation and immunohistochemistry, to confirm the diagnosis. Treatment for CMs often involves aggressive interventions such as surgical excision or systemic chemotherapy, whereas the primary goals for management of HS focus on alleviating chronic inflammation, preventing superinfections, and managing pain. Consequently, physicians must adeptly distinguish CMs from HS in order to direct appropriate diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Author & Publication Information

Authors: Vincent Pecora, BA1*; Archana Samynathan, MD1*; Adam Rosenfeld, MD1; Zoon Tariq, MD2; and Karl Saardi, MD1

Affiliations: 1The George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Washington, DC, USA; 2Department of Pathology, The George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA

ORCID: Pecora, 0009-0000-5427-5120; Tariq, 0009-0003-5618-1402

Author Contributions: V.P. and A.S. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosure: The authors disclose no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: Consent to use images for the publication of their cases was received from all 3 patients.

Correspondence: Karl Saardi, MD; 2150 Pennsylvania Ave NW Fl. 2 South, Washington, DC 20037; ksaardi@mfa.gwu.edu

Manuscript Accepted: December 17, 2024

References

1. Baig IT, Nguyen QD, Hickson MAS, Ciurea A. Metastatic adenocarcinoma mimicking hidradenitis suppurativa. JAAD Case Rep. 2022;27:91-93. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2022.07.026

2. Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, Aydogan M, Ciman Y. Cutaneous metastases: different clinical presentations—case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Rep. 2022;15(1):9553. doi:10.4081/dr.2022.9553

3. Sotoodian B, Abbas M, Brassard A. Hidradenitis suppurativa and the association with hematological malignancies. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(2):158-161. doi:10.1177/1203475416668161

4. Ballard K, Shuman VL. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Updated April 17, 2023. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534867/

5. Wong CY, Helm MA, Kalb RE, Helm TN, Zeitouni NC. The presentation, pathology, and current management strategies of cutaneous metastasis. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(9):499-504. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.118918

6. Strickley J, Jenson A, Yeon Jung J. Cutaneous metastasis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):173-197. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2018.08.008

7. Tricarico PM, Moltrasio C, Gradišek A, et al. Holistic health record for hidradenitis suppurativa patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8415. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11910-5

8. Zouboulis CC, Benhadou F, Byrd AS, et al. What causes hidradenitis suppurativa? 15 years after. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(12):1154-1170. doi:10.1111/exd.14214

9. Jfri A, Nassim D, O’Brien E, Gulliver W, Nikolakis G, Zouboulis CC. Prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(8):924-931. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1677

10. Teyateeti P, Ungtrakul T. Retrospective review of cutaneous metastasis among 11,418 patients with solid malignancy: a tertiary cancer center experience. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(29):e26737. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026737

11. Kazemi A, Carnaggio K, Clark M, Shephard C, Okoye GA. Optimal wound care management in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Dermatol Treat. 2011;29(2):165-167. doi:10.1080/09546634.2017.1342759