Heel Pressure Ulcers in Orthopedic Patients: A Prospective Study of Incidence and Risk Factors in an Acute Care Hospital

Abstract: Heel pressure ulcers (PU) are a major concern in orthopedic patients. A prospective 6-month study was conducted in an acute care hospital in Canada to determine the incidence of heel PU in an orthopedic population, evaluate the effect of patient and care variables on heel PU incidence, and describe the natural history/sequelae of Stage I heel PU. One hundred and fifty (150) patients (average age 70.6 years) admitted for elective orthopedic surgery or treatment of a fractured hip participated in the study.

A direct heel skin assessment was performed following admission and before discharge. Patients with a Stage I ulcer were assessed or contacted 1 week following discharge. The incidence of heel PU in this population was 13.3% CI (range 8% to 19%). Incidence was 16% in the hip fracture and 13% in the elective surgery group. PU incidence in the hip fracture group was significantly lower (P = 0.016) for patients receiving heel pressure relief measures (pillows, rolled sheets). In the elective surgery group, PU incidence rates were higher for patients with respiratory disease, lower hemoglobin, low pulse rate, and altered mental status (P <0.05). When both patient groups were combined, only the presence or absence of respiratory disease significantly affected PU incidence. Length of stay was an average of 3 days longer in all groups with a heel PU but the difference was not statistically significant. One week following discharge, 13 of the 17 (76%) Stage I heel PU had resolved, one remained unchanged, and two were assessed as deep tissue injury (11%) and one as Stage II. These incidence rates are similar to those reported in other countries and confirm that efforts to reduce heel PU incidence rates are needed.

Please address correspondence to: Karen E. Campbell, RN, MScN, PhD, 84 Meridene Circle West, London, Ontario N5X 1G2, Canada; email: Karen.campbell@sjhc.london.on.ca.

The extent of the problem of pressure ulcers (PU) is assessed using prevalence and incidence studies. However, few PU prevalence and incidence of studies have been conducted in Canada. Based on existing data from varied healthcare settings across Canada between 1990 and 2003, obtained from published and unpublished sources,1 Canadian prevalence estimates of PU for individuals of all ages receiving healthcare in hospitals, long-term care facilities, or at home varies from 15% to almost 30%, with an overall prevalence of 26%.1 Variations occur within levels of care; the estimated prevalence in acute care is 25.1%; nonacute care, 29.9%; mixed health settings, 22%; and community care, 15.1%.1

For clarity, prevalence is defined by Baumgarten2 as the proportion of a population that has a disease or condition such as a PU at a particular point in time. PU incidence is defined as the proportion of a population initially free of PU that develops the condition over a particular time period.3 PU incidence varies by level of care (ie, acute, rehabilitation, long-term, and community care). According to North American and international studies, incidence of all PU Stage I and higher in acute care ranges from 1.1% to 17.9%.4–12 Incidence rates in long-term care vary from 2.2% to 23.9%.11–14 Among acute care populations in the US and the Netherlands, PU incidence in surgical patients has been found to range from 13% to 21.5%.15–17 Incidence also can vary within specific patient populations. Among elderly people in acute care in the US, PU incidence was estimated to be 6.2%.18 An incidence study of lower extremity PU in the elderly completed among bedbound long-term care patients in Japan estimated the incidence at 16.6%, with heels and toes having the highest proportion of PU.19

PU incidence on all parts of the body has been studied on a general orthopedic unit; in one study, incidence was 20.3%.20 In other studies that examined PU incidence prospectively in an acute care population of hip fracture patients specifically, PU incidence ranged from 16% to 55%.21,22

PU incidence on all parts of the body has been studied on a general orthopedic unit; in one study, incidence was 20.3%.20 In other studies that examined PU incidence prospectively in an acute care population of hip fracture patients specifically, PU incidence ranged from 16% to 55%.21,22

Many reports12,15,23–26 have suggested the heel is one of the common sites of PU. An observational cross-sectional cohort study by VanGilder et al12 conducted in all care settings among almost 450,000 patients found that heels were the second most common site for PU after the sacrum. A prospective study25 performed in acute care and involving more than 39,000 patients found prevalence of heel PU is increasing while the prevalence of ulcers on other body locations has stayed the same or declined.

Information about the incidence and risk factors of heel PU in acute orthopedic units in Canada is lacking. In southwestern Ontario, this has been identified as a clinical problem of concern. Many elderly people require orthopedic procedures and if individuals develop heel PU, length of hospital stay,27 mortality,28 and costs29 can increase substantially. Heel PU also have been shown to reduce quality of life30 and limit rehabilitation. Because available PU risk assessment and prevention literature did not address the authors’ specific geographic location and setting, a prospective study was conducted to determine 1) the incidence of heel PU in an orthopedic population of an acute care hospital in Canada; 2) demographic, procedural, and prevention practices and medical risk factors associated with increased risk of developing a heel PU; and 3) the natural history/sequelae of Stage I heel PU.

Literature Review

Very little research has been performed on the incidence of heel ulcers specifically. Incidence of heel PU in all acute care patients ranged from 13.5% to 26.8% in two separate studies.31,32 The first study31 was conducted on four nursing units of an acute care hospital with the highest prevalence of heel PU (n = 432 patients); the second study32 was conducted on four medical surgical units (n = 113 patients). In a long-term care facility, the monthly incidence of heel PU was found to range from 0% to 9.1%.33 A retrospective chart review34 of orthopedic patients who had epidural blocks or peripheral nerve blocks rather than general anesthetics (n = 355) found a 2.5% incidence of heel PU.

Ideally, rigorous incidence studies need to be prospective and include a physical examination by an assessor trained to determine the presence of PU. Chart audits can underestimate incidence. A chart audit study35 in Sweden (n = 144) underestimated the actual incidence found on examination by more than 50%. Also, assessments need to occur at predetermined time intervals22; in hospitals, this is often on admission and at the average length of stay (LOS) day or discharge, whichever comes first.

A combination of extrinsic and intrinsic factors identifies patient susceptibility to or risks of developing PU, illustrating the interaction between environmental and individual influences and demonstrating their impact on health and disability. Once a person has developed a PU, these same risk factors are barriers to healing if they are not addressed and corrected. Some influences — ie, modifiable factors — can be corrected while others cannot. These risk factors have been studied extensively.

Risk factors for PU have been studied in people with a fractured hip in acute care hospitals. Risk factors specific to this population include increased LOS,36 age >70 years, dehydration, moist skin, total Braden Score, friction, nutrition, sensory perception, diabetes mellitus, pulmonary disease,22 wait time for the operating room (OR),37–39 low hemoglobin,39 intensive care unit (ICU) stay,37 longer surgical procedure,37 and general anesthetic.37

Two studies examined risk factors specific to hospital-acquired heel ulcers (ie, friction, shear, moisture,31 type 2 diabetes, and PVD40) using Braden Risk Assessment subscale scores and total Braden Scale score.40 Risk assessment scales are used to determine individual patient risk of developing a PU as well as care planning and prevention of PU. Much effort has been exerted to develop risk assessment scales that will predict which patients will develop PU. An overall risk score is established based on criteria considered to be risk factors. Once a patient’s risk level is identified, nurses implement directed prevention strategies. The Braden Risk Assessment Scale41 appears to be the most commonly used PU risk assessment scale in North America.

Recently, a systematic review of risk assessment scales for PU prevention was conducted to determine the effectiveness of using risk assessment scales in practice to prevent PU and to determine the degree of validation of different PU risk assessment scales and the effectiveness of various risk scales as indicators of a patient’s risk of developing PU. Researchers searched 14 databases; 33 studies were found that met the author’s criteria for inclusion. The Braden Scale41,42 was determined to provide optimal validation and the best overall balance between sensitivity and specificity; the authors concluded the Braden score is a good PU risk predictor in all care settings.43 Other commonly used scales include the Norton,44,45 Gosnell,46,47 Waterlow,48 and many others developed by local jurisdictions but most have not been validated.

Methods

Setting. The research was conducted in an academic 850-bed, tertiary care facility (London Health Sciences Centre, University Hospital [UH]), located in a small urban center in southwestern Ontario, Canada. The facility has 36 inpatient, acute, orthopedic surgery beds and often 15 additional orthopedic surgery patients on other units. Approximately 1,300 elective hip and knee replacements are performed annually and care is provided for 200 patients with fractured hips.

Ethics approval. Approval to conduct the study was obtained from the Research Ethics Board at the local university and from the hospital research committee.

Study design. In this prospective study, consecutive orthopedic patients admitted to UH between June 2006 and January 2007 were asked to participate. Patients were assessed on admission and at discharge to identify associated risk factors and to determine if they developed a heel PU. Patients with Stage I ulcers were followed-up 1 week after discharge by home visit if they lived in the city or by telephone if they were from out of town. Participants were classified as: hip fracture — admitted for surgical or nonsurgical management of hip fracture at UH; or elective surgery — admitted to undergo a surgical procedure to a lower extremity at UH.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria. Participants were included if they or their substitute decision-maker provided written informed consent to participate in the research study; were older than 18 years; had an orthopedic condition of the pelvis, hip, or lower extremity; and were ulcer-free on both heels on admission.

Participants were excluded if they were actively dying or if it was impossible to view both heels for any reason (eg, excessive pain or cast in place).

Sample size determination and calculation. No published reports estimating the incidence of heel ulcers in this patient population were found and information about heel ulcers in the Canadian healthcare system was limited, making it difficult to determine a statistically appropriate sample size. Certain assumptions were made to complete the sample size calculation: 1) calculation numbers were based on the fact that a future prevention study was planned and post implementation incidence also would be calculated; 2) it was anticipated that incidence rates would be different between the elective and the hip fracture patients because the latter group would be older and have more predisposing risk factors; 3) the authors wanted to have similar numbers of patients in both groups; 4) a higher proportion of unpreventable heel PU was anticipated in the hip fracture group; 5) PU prevalence in patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery across the facility was 8.7% in 2002. Clinical staff members estimated the number of heel PU has risen since 2002. Because published estimates of PU incidence in hip fracture patients were between 8% and 55%37,49,50 — based on a study31 that estimated the incidence of heel PU in acute care to be 26.8% — for this study, the estimated incidence of PU in the hip fracture group was 27%.

Elective patients. Using an alpha level of 0.05, beta of 0.20, and confidence interval (CI) widths of 12%, the sample size necessary to detect a change in the incidence rate from 10% before implementation of the prevention program (to be addressed in a later publication) to 1% after program implementation would require 100 participants who were undergoing elective surgical repair.51

Fractured hip. Using an alpha level of 0.05 and beta of 0.20 with CI widths of 17%, the sample size necessary to detect a change in incidence rate from 27% before to 10% after program implementation would require 100 participants who were admitted with hip fractures.51

Study procedures.

Direct heel skin assessment. Expert skin assessors (the primary author, a wound care APN — not members of the orthopedic team) examined skin on the posterior, lateral, and medial surfaces of both heels at admission and at discharge for heel PU. During these assessments, severity of each PU was classified using the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel’s (NPUAP) staging system in place in June 2006. Although this study was conducted before the current NPUAP staging52 (February 2007) that included suspected deep tissue injury (DTI), suspected DTI was included in this study. Any PU identified was reported to the participant’s nurse. Nurses were instructed to follow current care procedures to manage the ulcers. The assessor recorded the type of mattress used by the participant, whether he/she was using a heel PU protection device, and whether the patient had a PU on any other part of his/her body. Participants were assessed twice — the first time within 72 hours of admission and the second at discharge or after the average LOS, whichever came first. The anticipated average LOS for patients undergoing knee replacements and for patients with hip fractures and hip replacements were 5 and 7 days, respectively. Any participant with a Stage I heel PU on discharge was followed-up 1 week post-discharge to reassess the heel PU and determine if the ulcer was open and required a dressing. For participants outside of the urban center, follow-up was completed by telephone. These measures were standard procedure.

Medical chart review. Participants’ medical charts were reviewed to obtain demographic data such as age and gender and to evaluate potential risk factors associated with PU. The procedural and medical factors reviewed included wait time to go to the OR; surgical procedure and postoperative complications (eg, ICU stay, blood loss, hypotension, infection); transfusions; and height and weight. Neurological factors reviewed included motor or sensory deficits of the lower legs and comorbid conditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, cancer, low blood pressure, congestive heart failure, respiratory disease). Lab values reviewed were hemoglobin, albumin, and pre-albumin. Documentation of the following practices for PU prevention were noted: completed risk assessment (Braden) with score and associated referrals to physical therapy (PT), occupational therapy (OT), or a registered dietitian (RD) and use of pressure redistribution measures (mattresses, heel PU prevention strategies).

Statistical analysis. The association between the presence of a heel PU on discharge and various dichotomous risk factors was determined using chi-squared tests. Individual risk factors measured as continuous variables in relation to heel PU on discharge were assessed using a Student t-test. Descriptive statistics were utilized to describe the population under study. The incidence estimates were expressed as percentages with 95% CI. Data were extracted to SPSS version 3.0 (Chicago, IL).

Results

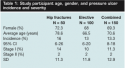

Of the 50 hip fracture and 100 elective surgery patients assessed, the heel PU incidence for participants with fractured hips and those undergoing elective surgery was 16% (n = 8) and 13% (n = 13), respectively; the combined incidence was 13.3% with 95% CI of 8% to 18% (see Table 1). Because the incidence rates were  similar, the two groups were combined. All PU were Stage I and Stage II; no Stage III or Stage IV PU were detected. All Stage I heel PU (n = 17) were followed-up 1 week after discharge; of these, 13 (76%) were completely resolved, two ulcers were assessed to be DTI, one ulcer was a Stage II, and one ulcer remained Stage I. It should be noted that data collection was stopped after the fiftieth hip fracture patient because the nurses were lifting heels off the bed and no PU occurred after subject 30 — ie, the nurses were preventing heel PU.

similar, the two groups were combined. All PU were Stage I and Stage II; no Stage III or Stage IV PU were detected. All Stage I heel PU (n = 17) were followed-up 1 week after discharge; of these, 13 (76%) were completely resolved, two ulcers were assessed to be DTI, one ulcer was a Stage II, and one ulcer remained Stage I. It should be noted that data collection was stopped after the fiftieth hip fracture patient because the nurses were lifting heels off the bed and no PU occurred after subject 30 — ie, the nurses were preventing heel PU.

Risk factors for development of heel ulcers. Overall, significant differences between assessed risk factors were seen between participants with and without a heel PU. In participants with hip fracture, eight of patients who did and 42 of patients who did not use a heel device had a PU at discharge (see Table 2). In the elective group, the proportion of patients who developed a heel PU was significantly higher in patients with respiratory disease, low hemoglobin, decreased pulse, and altered mental status. In the combined patient groups, the incidence of heel PU also was higher in patients with respiratory disease.

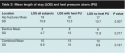

LOS and heel PU. Mean LOS for the elective patients and patients with fractured hips subjects was 6 days and 18 days, respectively; for the combined group (n = 150), LOS was 10 days (see Table 3).

In the combined group, mean LOS of participants with a heel ulcer was 3 days (SD = 8.9) more than for participants without heel ulcers. Although this was not statistically significant due to the wide variance in the data, it is clinically significant. The same is true for the fractured hip patients and the elective patients — average LOS was 3 (10.9) and 2 (4.7) days longer, respectively; however, this difference also was not statistically significant.

In the combined group, mean LOS of participants with a heel ulcer was 3 days (SD = 8.9) more than for participants without heel ulcers. Although this was not statistically significant due to the wide variance in the data, it is clinically significant. The same is true for the fractured hip patients and the elective patients — average LOS was 3 (10.9) and 2 (4.7) days longer, respectively; however, this difference also was not statistically significant.

Current PU prevention strategies. Participants’ chart reviews indicated that no risk assessments were performed before this initiative. Researchers found few assessments and referrals for nutritional deficiencies (eg, missing weight loss history, albumin or pre-albumin not ordered). Referral to PT was provided for all patients and OT was routinely ordered for all hip fracture and hip replacement patients. In all but one case, heel PU were first identified by the researcher, not the clinical staff. Medical history was minimal unless internal medicine or geriatrics services were consulted. All patients had at least a pressure-reducing foam replacement mattress; 6.6% of patients had more advanced therapeutic mattresses. Only 6% of the elective patients were provided special heel PU prevention measures. Heel PU prevention measures were implemented for 38% of hip fracture patients and to the last 25 subjects enrolled in the study. The measures most commonly implemented were the use of folded sheets and pillows.

Discussion

Incidence of heel PU in the acute orthopedic population in this study was 13.3%, which is similar to a recent report32 of heel PU incidence in all medical and surgical patients in an acute care hospital (13.5% and 13.8%). In a study by Tourtual et al31 reported 10 years ago, the incidence of heel PU was 26.8% — the majority were Stage I (94.6%) and Stage II (5.4%) with no Stage III or Stage IV. The percentages of Stage I and Stage II ulcers are similar to the findings in the current study where 84% of all heel PU were Stage I, 15% were Stage II, and no Stage III or Stage IV heel PU were noted. The absence of less severe heel PU may have occurred because of the short time frame between assessments (5 to 7 days). The incidence reported in Tourtual et al’s31 study is much higher than the incidence currently reported; in that study, only the four hospital units that had the highest number of reported heel PU were assessed for heel PU. Therefore, the sample population was different and may have affected the reported incidence. Incidence of heel PU was 13.3% at UH, an accurate estimate because the proportion of the total population recruited into the study over the 6-month study period was very high and the patients were enrolled consecutively.

Approximately 75% of the Stage I heel PU resolved; 18% deteriorated 1 week after discharge from acute orthopedics. A prospective, descriptive, comparative study53 in the Netherlands of patients in long-term and acute care facilities (N = 183) that followed Stage I PU (staged according to AHCPR guidelines using a clear round convex glass to determine whether discoloration blanched) found 50% resolved in a second visit the same day. Of the remaining Stage I PU, 22% deteriorated.

Risk factors for heel PU at UH in the elective group were the presence of respiratory disease, low hemoglobin, decreased pulse, and altered mental status. Low hemoglobin findings are similar to risk factors related to all heel ulcers in acute care31 and two of the risk factors are similar to research in the fractured hip population where pulmonary disease22 and low hemoglobin39 were found to be substantial. When UH groups were combined, the only substantial risk factor was respiratory disease, findings similar to Lindholm.22 This may be due to the lowered levels of oxygen due to respiratory disease combined with the even lower levels of oxygen due to the distance from the heart. When looking at the hip fracture group independently, only the use of heel pressure-relieving measures (rolled sheets, pillows, or a device) was associated with patients having no heel PU on discharge.

Although differences in LOS between participants who did or did not have heel PU were not statistically significant, they may be clinically important. Participants in the elective surgery group with a heel PU had an average 2-day longer LOS and in the hip fracture and combined groups the mean difference in LOS for patients with a heel PU was 3 days. It seems likely that having a PU is more common in persons who are unwell and the heel PU is an indicator of disease/condition acuity. In an Australian study,27 where a probabilistic model was used in a tertiary referral hospital (n = 1,747), having any PU was found to increase LOS in acute care hospitals by 4.1 days and having an infected PU increased LOS by 12.57 days. In the US, having a heel PU in acute care was associated with a LOS increase of 8 days.31

Many PU prevention strategies were in place in the authors’ facility: all patients had a foam pressure-reduction mattress, referrals were made automatically to PT and OT, and the use of a risk assessment tool had been mandated but not always used. After several months of data collection for the study, the researcher noticed that pillows often were used with the fractured hip patients, but this change in practice was not noted in the treatment of elective surgery patients. All heel ulcers in the hip fracture group occurred in the first 30 participants recruited; subsequently, pillow use increased. No heel PU prevention measures were used at all in the first 25 participants enrolled. All of the 19 heel prevention measures observed were utilized in the last 25 patients. The observed change in practice and resultant decrease in PU incidence among hip fracture patients led to discontinuation of patient recruitment after 50 patients were enrolled.

Limitations

It is possible that the incidence estimates of this study were affected by the method of determining incidence — ie, not daily visits, but assessments at admission and discharge. Although this approach might be expected to underestimate, the authors’ estimate was similar to published findings. Additionally, the assessment schedule used was similar to what was noted in other studies.

The second limitation of the study was the practice change that occurred before the targeted sample size of 100 hip fracture patients was reached. This unintended consequence of the study was a good outcome for patients but limited recruitment in the hip fracture group to 50 participants. Also, the absence of multivariate analysis and limited knowledge about which risk factors are correlated were potential limitations.

Conclusion

The incidence of heel PU in this acute care facility was 16% (95% CI, 6%–26%) for patients with fractured hips and 13% (95% CI, 6%–20%) for elective surgery patients. The incidence of PU in both groups was similar and when the groups were combined, the incidence was 13.3% (95% CI, 8%–19%). Approximately 75% of Stage I heel PU resolved 1 week after discharge and 18% deteriorated.

In the elective surgery patients, the incidence of heel PU was significantly higher in participants with respiratory disease, lower hemoglobin, pulse, and altered mental status. In the hip fracture group, only the use of heel pressure-relieving measures was associated with no heel PU at discharge. When both patient groups were combined, the incidence of heel PU was significantly higher in patients with than in patients without respiratory disease. LOS was higher in all groups with a heel PU and although not statistically significant, this observation may have clinical and potential care and cost implications. Additional studies to increase understanding of heel PU in the acute care setting are warranted.

This research project was funded by the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario, the Canadian Nurses Foundation, and the London Health Sciences Center.

1. Woodbury MG, Houghton PE. Prevalence of pressure ulcers in Canadian healthcare settings. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50(10):22–38.

2. Baumgarten M. Designing prevalence and incidence studies. Adv Wound Care. 1998;11(6):287–293.

3. Frantz RA. Measuring prevalence and incidence of pressure ulcers. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(1):21–24.

4. Cole L, Nesbitt C. A three-year multiphase pressure ulcer prevalence/incidence study in a regional referral hospital. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004;50(11):32–40.

5. Olson B, Langemo D, Burd C, Hanson D, Hunter S, Cathcart-Silberberg T. Pressure ulcer incidence in an acute care setting. J WOCN. 1996;23(1):15–22.

6. Langemo DK, Olson B, Hunter S, Hanson D, Burd C, Cathcart-Silberberg T. Incidence and prediction of pressure ulcers in five patient care settings. Decubitus. 1991;4(3):25–30.

7. Williams S, Watret L, Pell J. Case-mix adjusted incidence of pressure ulcers in acute medical and surgical wards. J Tissue Viabil. 2001;11(4):139–142.

8. Whittington K, Patrick M, Roberts JL. A national study of pressure ulcer prevalence and incidence in acute care hospitals. J WOCN. 2000;27(4):209–215.

9. Gerson LW. The incidence of pressure sores in active treatment hospitals. Int J Nurs Stud. 1975;12(4):201–204.

10. Gosnell DJ, Johannsen J, Ayres M. Pressure ulcer incidence and severity in a community hospital. Decubitus. 1992;5(5):56–62.

11. Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M, Champagne M, Ruby E. Multi-site study of incidence of pressure ulcers and the relationship between risk level, demographic characteristics, diagnoses, and prescription of preventive interventions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(1):22–30.

12. VanGilder C, MacFarlane GD, Meyer S. Results of nine international pressure ulcer prevalence surveys: 1989 to 2005. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2008;54(2):40–54.

13. Davis CM, Caseby NG. Prevalence and incidence studies of pressure ulcers in two long-term care facilities in Canada. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2001;47(11):28–34.

14. Berlowitz DR, Bezerra HQ, Brandeis GH, Kader B, Anderson JJ. Are we improving the quality of nursing home care: the case of pressure ulcers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(1):59–62.

15. Schoonhoven L, Defloor T, Grypdonck MHF. Incidence of pressure ulcers due to surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(4):479–487.

16. Hicks DJ. An incidence study of pressure sores following surgery. ANA Clin Sess. 1970:49–54.

17. Schultz A, Bien M, Dumond K, Brown K, Myers A. Etiology and incidence of pressure ulcers in surgical patients. AORN J. 1999;70(3):434–449.

18. Baumgarten M, Margolis DJ, Localio AR, et al. Pressure ulcers among elderly patients early in the hospital stay. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(7):749–754.

19. Okuwa M, Sanada H, Sugama J, et al. A prospective cohort study of lower-extremity pressure ulcer risk among bedfast older adults. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19(7):391–397.

20. Roberts BV, Goldstone LA. A survey of pressure sores in the over sixties on two orthopaedic wards. Int J Nurs Stud. 1979;16(4):355–364.

21. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjödén P. Reduced incidence of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: a 2-year follow-up of quality indicators. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13(5):399–407.

22. Lindholm C, Sterner E, Romanelli M, et al. Hip fracture and pressure ulcers — the Pan-European Pressure Ulcer Study — intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors. Int Wound J. 2008;5(2):315–328.

23. Versluysen M. Pressure sores in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67(1):10–13.

24. Bours GJ, Halfens RJ, Lubbers M, Haalboom JR. The development of a national registration form to measure the prevalence of pressure ulcers in The Netherlands. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1999;45(11):28–36.

25. Barczak CA, Barnett RI, Childs EJ, Bosley LM. Fourth national pressure ulcer prevalence survey. Adv Wound Care. 1997;10(4):18–26.

26. Goodridge DM, Sloan JA, LeDoyen YM, McKenzie J-, Knight WE, Gayari M. Risk-assessment scores, prevention strategies, and the incidence of pressure ulcers among the elderly in four Canadian health-care facilities. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(2):23–44.

27. Graves N, Birrell FA, Whitby M. Modeling the economic losses from pressure ulcers among hospitalized patients in Australia. Wound Repair Regen. 2005;13(5):462–467.

28. Brandeis GH, Morris JN, Nash DJ, Lipsitz LA. The epidemiology and natural history of pressure ulcers in elderly nursing home residents. JAMA. 1990;264(22):2905–2909.

29. Allman RM, Laprade CA, Noel LB. Pressure sores among hospitalized patients. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105(3):337–342.

30. Langemo DK, Melland H, Hanson D, Olson B, Hunter S. The lived experience of having a pressure ulcer: a qualitative analysis. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2000;13(5):225–235.

31. Tourtual DM, Riesenberg LA, Korutz CJ, Semo AH, Asef A, Talati K, et al. Predictors of hospital-acquired heel pressure ulcers. Ostomy Wound Manage. 1997;43(9):24–34.

32. McElhinny ML, Hooper C. Reducing hospital-acquired heel ulcer rates in an acute care facility: an evaluation of a nurse-driven performance improvement project. J WOCN. 2008;35(1):79–83.

33. Frain R. Decreasing the incidence of heel pressure ulcers in long-term care by increasing awareness: results of a 1-year program. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2008;54(2):62–67.

34. Edwards JL, Pandit H, Popat MT. Perioperative analgesia: a factor in the development of heel pressure ulcers? Br J Nurs. 2006;15(6):S20–S25.

35. Gunningberg L, Ehrenberg L. Accuracy and quality in the nursing documentation of pressure ulcers: a comparison of record content and patient examination. J WOCN. 2004;31(6):328–335.

36. Stotts NA, Deosaransingh K, Roll FJ, Newman J. Underutilization of pressure ulcer risk assessment in hip fracture patients. Adv Wound Care. 1998;11(1):32–38.

37. Baumgarten M, Margolis D, Berlin JA, et al. Risk factors for pressure ulcers among elderly hip fracture patients. Wound Repair Regen. 2003;11(2):96–103.

38. Al-Ani AN, Samuelsson B, Tidermark J, et al. Early operation on patients with a hip fracture improved the ability to return to independent living: a prospective study of 850 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(7):1436–1442.

39. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjödén PO. Effect of visco-elastic foam mattresses on the development of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures. J Wound Care. 2000;9(10):455–460.

40. Walsh JS, Plonczynski DJ. Evaluation of a protocol for prevention of facility-acquired heel pressure ulcers. J WOCN. 2007;34(2):178–183.

41. Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res. 1987;36(4):205–210.

42. Braden B, Bergstrom N. A conceptual schema for the study of the etiology of pressure sores. Rehabil Nurs. 1987;12(1):8–12.

43. Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, Garcia-Fernandez FP, Lopez-Medina IM, Alvarez-Nieto C. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):94–110.

44. Norton D. Calculating the risk: reflections on the Norton scale. Decubitus. 1989;2(3):24–31.

45. Exton-Smith AN, Norton D, McLaren R. An Investigation of Geriatric Nursing Problems in the Hospital. London, UK: Churchill Livingston;1975.

46. Gosnell DJ. Pressure sore risk assessment instrument revision. J Enterostomal Ther. 1989;16(6):272.

47. Gosnell DJ. Pressure sore risk assessment. Part II. Analysis of risk factors. Decubitus. 1989;2(3):40–43.

48. Waterlow J. Pressure sores: a risk assessment card. Nurs Times. 1985;81(48):49–55.

49. Cuddigan J, Berlowitz DR, Ayello EA. Prevalence, incidence, and implications for the future: an executive summary of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2001;14(4):208–215.

50. Gunningberg L, Lindholm C, Carlsson M, Sjödén P. The development of pressure ulcers in patients with hip fractures: inadequate nursing documentation is still a problem. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(5):1155–1164.

51. Colton T. Statistics in Medicine, 1st ed. Boston, MA: Little Brown and Company;1974.

52. National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. NPUAP announces new pressure ulcer definition and staging. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2007;20:184–187.

53. Halfens RJG, Bours GJJW, Van Ast W. Relevance of the diagnosis ‘stage 1 pressure ulcer’: an empirical study of the clinical course of stage 1 ulcers in acute care and long-term care hospital populations. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(6):748–757.