Empirical Studies

Health-related Quality of Life and Self-Esteem in Patients with Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Results of a Cross-sectional Comparative Study

Index: Ostomy Wound Management 2011;57(3):36–43.

Key Words: cross-sectional comparative study, diabetes mellitus, diabetic foot ulcer, quality of life, self-esteemAbstract

To evaluate health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and self-esteem in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), a cross-sectional, comparative study was conducted among 35 consecutive patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) attending outpatient clinics in Pouso Alegre, Brazil. Fifteen (15) patients with and 20 without a DFU participated in the study. Demographic variables were obtained and HRQoL and self-esteem were assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) and Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. In both groups, 80% of patients were women. Average age did not differ significantly between the DFU and control groups (average 56 [SD 8.42] and 52 years [SD 6.68], respectively) but disease duration was significantly longer (P P = 0.043), role physical (P = 0.003), social functioning (P = 0.022), and role emotional (P = 0.001). Self-esteem scores were similar in both groups. The results of this study confirm that patient HRQoL is negatively affected by the presence of a DFU. Wound prevention programs for patients with DM may help reduce the scope of this problem while DFU treatment programs that include psychological support may improve patient QoL. Potential Conflicts of Interest: none disclosed Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a major public health problem with increasing incidence, prevalence, and associated costs. DM is associated with complications that affect productivity, quality of life (QoL), and longevity. Estimates show that 15% of the patients with DM will develop at least one foot ulcer in their lifetime.1,2 Foot ulcers are among the most common complications of type 2 DM, often preceded by various disorders that affect the skin, nerves, joints, muscles, and arteries of the foot, causing the development of the so-called “diabetic foot”2 — ie, a complex clinicopathological condition that increases the risk of ulceration, impairment, disability, early retirement, lower limb amputation, and mortality.3 In the US, diabetic foot ulcers are responsible for more than half of all nontraumatic amputations of the lower limbs, corresponding to 56% to 83% of the estimated 125,000 lower extremity amputations performed annually.4,5

The presence or history of a foot ulcer has a large impact on physical functioning and mobility and affects patient QoL. 6-8 Interest in QoL as a clinical assessment and economic model variable has increased substantially.9,10 Patient QoL plays an important role in the development of health services11-14; QoL studies in patients with DM and foot ulcers may help improve prevention and treatment protocols of care. 6,15,16

The purpose of this study was to assess and compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and self-esteem of patients with DM with and without foot ulcers.

Foot ulcers are among the most common complications of type 2 DM, often preceded by various disorders that affect the skin, nerves, joints, muscles, and arteries of the foot, causing the development of the so-called “diabetic foot”2 — ie, a complex clinicopathological condition that increases the risk of ulceration, impairment, disability, early retirement, lower limb amputation, and mortality.3 In the US, diabetic foot ulcers are responsible for more than half of all nontraumatic amputations of the lower limbs, corresponding to 56% to 83% of the estimated 125,000 lower extremity amputations performed annually.4,5

The presence or history of a foot ulcer has a large impact on physical functioning and mobility and affects patient QoL. 6-8 Interest in QoL as a clinical assessment and economic model variable has increased substantially.9,10 Patient QoL plays an important role in the development of health services11-14; QoL studies in patients with DM and foot ulcers may help improve prevention and treatment protocols of care. 6,15,16

The purpose of this study was to assess and compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and self-esteem of patients with DM with and without foot ulcers.

Methods and Procedures

This cross-sectional comparative study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Sapucaí Valley University (UNIVÁS), MG, Brazil. After a full explanation of the study was provided, written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants. DM patients with a diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) (study group) and patients with DM without ulcers (control group), all 30 to 70 years of age, were consecutively selected for study participation at the outpatient clinics of Samuel Libânio University Hospital (HCSL) and the City Center for Diabetes Education (CEMED), MG, Brazil. Excluded from study participation were patients who were hospitalized, had a history of or were recommended to undergo a lower limb amputation, or had uncontrolled systemic diseases (eg, systemic arterial hypertension, cardiopathies, and collagen and rheumatic diseases). All patients underwent a clinical and physical examination performed by a physician before being assessed by the research nurses. Patients with DM and controlled comorbidities were eligible to participate after receiving appropriate treatment(s). Variables. Demographic variables and clinical characteristics (name, gender, age, race, educational level, diabetes duration) were assessed and recorded after informed consent was obtained at the start of the study. HRQoL. HRQoL was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire, which had been translated into Portuguese, culturally adapted, and validated for Brazil.10 There is no single overall score for the SF-36 questionnaire; instead, it contains one comparative item assessing changes in health over the past year and 35 items grouped into eight domains (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health) assessing the patient’s perception of health over the last 4 weeks. Scores on each dimension range from 0 to 100, with 0 corresponding to the worst health status and 100 to the best health status. Each domain is evaluated and analyzed separately. Self-esteem. Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (UNIFESP-EPM), which was translated and validated for use in Brazil by Dini et al.13 This is a 10-item measure in which the total score ranges from 0 to 30, with lower scores indicating higher self-esteem. The Brazilian version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale has been shown to be a valid, reliable, and reproducible measure of self-esteem.13 The first author of the present study administered the paper-pencil questionnaires. Because of the low educational level of the study population, an interview approach was used. Each multiple-choice question and respective alternative answers were read aloud exactly as written, as many times as needed, and the investigator recorded the responses. Care was taken not to introduce any bias and not to answer any question on the behalf of the patient. Data. Data were entered into Excel® spreadsheets and statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) release 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Pearson’s chi-square test was used to compare the frequency distribution of categorical variables between groups. Fisher’s exact test was used for expected values P ≤0.05.Results

The control group consisted of 20 patients with DM without ulcers (80% women, 20% men, P P P = 0.05). Caucasian patients predominated in both the study (86.7%) and control (90%) groups; no significant differences in race were found between groups (P >0.999). Also, no significant differences were noted in educational level between groups (P = 0.483); 8.6% of the total sample was illiterate and 65.7% had completed an elementary school education only. Significant differences between groups were found in the mean scores of the following SF-36 domains: physical functioning, role physical, social functioning, and role emotional, indicating that patients with foot ulcers had a lower HRQoL than patients without ulcers. In all SF-36 domains, the mean scores for patients with foot ulcers were lower than those for patients without ulcers (see Table 1).

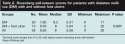

No differences in self-esteem between groups were observed (see Table 2).

No significant differences between genders were found in the following SF-36 domains: role physical (RP), social functioning (SF), and role emotional (RE). On average, women had higher HRQoL scores than men. Self-esteem scores were similar for both groups (see Table 3).

Significant differences between groups were found in the mean scores of the following SF-36 domains: physical functioning, role physical, social functioning, and role emotional, indicating that patients with foot ulcers had a lower HRQoL than patients without ulcers. In all SF-36 domains, the mean scores for patients with foot ulcers were lower than those for patients without ulcers (see Table 1).

No differences in self-esteem between groups were observed (see Table 2).

No significant differences between genders were found in the following SF-36 domains: role physical (RP), social functioning (SF), and role emotional (RE). On average, women had higher HRQoL scores than men. Self-esteem scores were similar for both groups (see Table 3).

Discussion

Diabetic foot ulcers cause pain and changes in lifestyle and QoL that may render the patient unable to perform normal activities. These ulcers are associated with high socioeconomic costs due to amputations, early retirement, loss of work capacity in the working-age group, work absenteeism, and hospital and medical costs.17-20 In Brazil, approximately 5 million people have DM; of those, 50% are unaware that they have the disease.19 Type 1 DM affects about 10% of this population. Among persons who know they have the disease, 90% have type 2 DM and 2% of type 2 DM patients have associated complications.19 No estimates of the number of individuals with diabetes-related wounds are available in Brazil.21-23 The direct cost of DM ranges between 2.5% and 15% of the country’s annual healthcare expenditures, depending on prevalence rates and level of services provided. Annual direct DM-associated costs are estimated to range from $0.8 billion in Argentina to $2 billion in Mexico and $3.9 billion in Brazil.22,23

DFUs are among the most common diabetes-related complications and are characterized by the presence of lesions on the feet caused by neurological (70% to 100% of cases) and vascular factors (10% of cases). DFU is a chronic complication that occurs (on average) 10 years after disease onset; it is the leading cause of hospital admissions among patients with DM. Patients with DFUs have a length of stay 59% longer than patients with DM without ulcers.5,23-27

In the present study, exclusion criteria comprised indication for amputation of the lower limbs or previous amputation, associated uncontrolled systemic diseases, and hospitalization, factors that by themselves could compromise QoL or self-esteem.6,10,15,24

The study group mean age was approximately 50 years, characterizing an adult but not elderly population that was already suffering from diabetes-related problems. The results of this study confirm that the presence of a DFU restricts mobility and negatively affects QoL and self-esteem. Most patients in the study group were men with mean disease duration of 12 years compared to an average duration of 8 years in the control group — a significant difference (P = 0.05). This finding confirms that risk of DFU increases with disease duration and underscores the importance of implementing prophylactic measures as soon as possible following diagnosis of the disease, especially in the male population that usually takes less care of their health compared with women.3,17

Health-related quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined QoL as “the individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.” This definition includes six domains: physical health, psychological state, levels of independence, social relationships, environmental features, and spiritual concerns.28-33

The SF-36 questionnaire used in this study is a generic instrument derived from a questionnaire for health evaluation (Medical Outcomes Study, MOS)7,34,35 and is the most commonly used generic instrument for measuring HRQoL around the world.36,37

According to D’Amorim,30 low patient educational level reduces the quality of information obtained with self-administered questionnaires. In the present study, 8.6% of the patients were illiterate and 65.7% had only elementary education. Patients with low sociocultural level and only elementary education are better assessed through interviews. The interview approach also increases study participation rates38; in the current study, 100% of participants completed the interview.

SF-36 scores were significantly lower in the study group than in the control group in the following domains: physical functioning (P = 0.043), role physical (P = 0.003), social functioning (P = 0.022), and role emotional (P = 0.001). Mean scores on all SF-36 domains were lower in the study group than in the control group.

Several studies have investigated the QoL of patients with foot ulcers.6,15-20,39-43 Current study results are similar to the findings of other studies using the RAND 36-Item Health Survey (RAND-36) and Walking Stairs Questionnaire (WSQ) that reported low QoL in patients with DFUs, especially concerning mobility and physical and social functioning.6,15,16 Tennvall and Apelqvist31 reported that the extensive impact of mobility limitations led to a cascade effect in every QoL domain.

Goodridge et al41 compared QoL parameters in 104 patients with healed and unhealed DFUs (defined as having a history of diabetic foot ulcers ≥6 months) who received care in a tertiary foot care clinic. Results using the Short Form 12 questionnaire showed that the unhealed DFU group had a greater reduction than the healed DFU group in overall physical health compared to patients with DM and no history of an ulcer, patients with hypertension, and persons in the general population. Additionally, significantly reduced QoL scores were found in the unhealed DFU group compared with the healed DFU group in several measures of physical health (P P 41

In another cross-sectional study, Ribu et al42 evaluated the HRQoL in patients with DFUs (n = 127) by comparing their HRQoL with that of a sample from the general population without diabetes (n = 5,903) and a subgroup with diabetes and no DFU (n = 221) to examine differences between groups by sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors. Data on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and HRQoL (SF-36) were obtained. In all the SF-36 domains and in the two SF-36 summary scales, patients with DFUs reported significantly lower HRQoL than the DM population without DFU. The most striking differences observed were in the role physical (32.1 versus 62.2, P P P P P P 42

In a multicenter prospective study, Nabuurs-Franssen et al43 evaluated HRQoL in 294 patients (ulcer duration ≥4 weeks) and 153 caregivers at three time points: baseline (T0), when the ulcer was healed or after 20 weeks (T1), and 3 months later (T2). The mean age of the patients was 60 years, 72% were male, and time since diagnosis of diabetes was 17 years. Patients reported a low HRQoL on all SF-36 domains. At T1, HRQoL scores in physical and social functioning were higher for patients with a healed versus a nonhealed ulcer (P P P 43 Price16 and Wild36 also reported a significant reduction in the QoL in patients with DFUs especially in role physical, social functioning, and mobility. The current study results suggest that DFUs reduce HRQoL, regardless of patient nationality.

Self-esteem. Generic instruments such as the SF-36 have the advantage of allowing QoL comparisons between patients with different diseases and between different socio-demographic groups. However, they do not allow evaluation of specific aspects of health, such as self-esteem. Therefore, it was important to complement the results from the SF-36 with the use of a specific instrument, such as the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (UNIFESP-EPM),7,13,14 to evaluate an important aspect of the human life — ie, self-esteem.13,14 In this study, the mean self-esteem score was higher in persons with a DFU than in the control group but the difference was not statistically significant.

The direct cost of DM ranges between 2.5% and 15% of the country’s annual healthcare expenditures, depending on prevalence rates and level of services provided. Annual direct DM-associated costs are estimated to range from $0.8 billion in Argentina to $2 billion in Mexico and $3.9 billion in Brazil.22,23

DFUs are among the most common diabetes-related complications and are characterized by the presence of lesions on the feet caused by neurological (70% to 100% of cases) and vascular factors (10% of cases). DFU is a chronic complication that occurs (on average) 10 years after disease onset; it is the leading cause of hospital admissions among patients with DM. Patients with DFUs have a length of stay 59% longer than patients with DM without ulcers.5,23-27

In the present study, exclusion criteria comprised indication for amputation of the lower limbs or previous amputation, associated uncontrolled systemic diseases, and hospitalization, factors that by themselves could compromise QoL or self-esteem.6,10,15,24

The study group mean age was approximately 50 years, characterizing an adult but not elderly population that was already suffering from diabetes-related problems. The results of this study confirm that the presence of a DFU restricts mobility and negatively affects QoL and self-esteem. Most patients in the study group were men with mean disease duration of 12 years compared to an average duration of 8 years in the control group — a significant difference (P = 0.05). This finding confirms that risk of DFU increases with disease duration and underscores the importance of implementing prophylactic measures as soon as possible following diagnosis of the disease, especially in the male population that usually takes less care of their health compared with women.3,17

Health-related quality of life. The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined QoL as “the individuals’ perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.” This definition includes six domains: physical health, psychological state, levels of independence, social relationships, environmental features, and spiritual concerns.28-33

The SF-36 questionnaire used in this study is a generic instrument derived from a questionnaire for health evaluation (Medical Outcomes Study, MOS)7,34,35 and is the most commonly used generic instrument for measuring HRQoL around the world.36,37

According to D’Amorim,30 low patient educational level reduces the quality of information obtained with self-administered questionnaires. In the present study, 8.6% of the patients were illiterate and 65.7% had only elementary education. Patients with low sociocultural level and only elementary education are better assessed through interviews. The interview approach also increases study participation rates38; in the current study, 100% of participants completed the interview.

SF-36 scores were significantly lower in the study group than in the control group in the following domains: physical functioning (P = 0.043), role physical (P = 0.003), social functioning (P = 0.022), and role emotional (P = 0.001). Mean scores on all SF-36 domains were lower in the study group than in the control group.

Several studies have investigated the QoL of patients with foot ulcers.6,15-20,39-43 Current study results are similar to the findings of other studies using the RAND 36-Item Health Survey (RAND-36) and Walking Stairs Questionnaire (WSQ) that reported low QoL in patients with DFUs, especially concerning mobility and physical and social functioning.6,15,16 Tennvall and Apelqvist31 reported that the extensive impact of mobility limitations led to a cascade effect in every QoL domain.

Goodridge et al41 compared QoL parameters in 104 patients with healed and unhealed DFUs (defined as having a history of diabetic foot ulcers ≥6 months) who received care in a tertiary foot care clinic. Results using the Short Form 12 questionnaire showed that the unhealed DFU group had a greater reduction than the healed DFU group in overall physical health compared to patients with DM and no history of an ulcer, patients with hypertension, and persons in the general population. Additionally, significantly reduced QoL scores were found in the unhealed DFU group compared with the healed DFU group in several measures of physical health (P P 41

In another cross-sectional study, Ribu et al42 evaluated the HRQoL in patients with DFUs (n = 127) by comparing their HRQoL with that of a sample from the general population without diabetes (n = 5,903) and a subgroup with diabetes and no DFU (n = 221) to examine differences between groups by sociodemographic characteristics and lifestyle factors. Data on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle, and HRQoL (SF-36) were obtained. In all the SF-36 domains and in the two SF-36 summary scales, patients with DFUs reported significantly lower HRQoL than the DM population without DFU. The most striking differences observed were in the role physical (32.1 versus 62.2, P P P P P P 42

In a multicenter prospective study, Nabuurs-Franssen et al43 evaluated HRQoL in 294 patients (ulcer duration ≥4 weeks) and 153 caregivers at three time points: baseline (T0), when the ulcer was healed or after 20 weeks (T1), and 3 months later (T2). The mean age of the patients was 60 years, 72% were male, and time since diagnosis of diabetes was 17 years. Patients reported a low HRQoL on all SF-36 domains. At T1, HRQoL scores in physical and social functioning were higher for patients with a healed versus a nonhealed ulcer (P P P 43 Price16 and Wild36 also reported a significant reduction in the QoL in patients with DFUs especially in role physical, social functioning, and mobility. The current study results suggest that DFUs reduce HRQoL, regardless of patient nationality.

Self-esteem. Generic instruments such as the SF-36 have the advantage of allowing QoL comparisons between patients with different diseases and between different socio-demographic groups. However, they do not allow evaluation of specific aspects of health, such as self-esteem. Therefore, it was important to complement the results from the SF-36 with the use of a specific instrument, such as the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (UNIFESP-EPM),7,13,14 to evaluate an important aspect of the human life — ie, self-esteem.13,14 In this study, the mean self-esteem score was higher in persons with a DFU than in the control group but the difference was not statistically significant.