Cardiovascular Health for Patients with Psoriasis: A Précis for Front-Line Clinicians

Abstract:

Psoriasis is a prevalent immune disease most notably recognized for its involvement of the skin and joints and for its impact on patient quality of life. More recently, it has been shown that not only do patients with psoriasis have a higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, and dyslipidemia, but they also appear to have an increased risk of myocardial infarction independent of these factors. Patients with severe forms of psoriasis also have been found to have increased mortality rates compared to those without psoriasis. The purpose of this review is to increase awareness of these associations among dermatologists and primary care providers to ensure that cardiovascular risk factors are evaluated and appropriately managed in patients with psoriasis.

Dr. Federman is a staff physician, Department of Medicine, VA Connecticut Health Care, West Haven, CT; and Professor of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. Dr. Shelling is a dermatology resident and Dr. Prodanovich is a dermatologist, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL. Dr. Gunderson is a staff physician, Department of Medicine, VA Connecticut Health Care; and Assistant Professor of Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine. Dr. Kirsner is a Professor of Dermatology, Department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Surgery; and Department of Epidemiology and Public Healing, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

Please address correspondence to: Daniel G. Federman, MD, VA Connecticut Health Care, 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, CT 06516; email: daniel.federman@va.gov.

Psoriasis affects nearly 2% to 3% of the world’s population, including 7 million Americans.1 Between 150,000 and 260,000 new cases are diagnosed annually; both young and old are affected. Racial and ethnic factors seem to influence the prevalence of psoriasis. There are no cases in the Samoan population, but up to 12% of persons in the Arctic Kasach’ye have psoriasis; within the US population, the prevalence in blacks is much lower than non-blacks.2 Although common, psoriasis has varied clinical presentations. Care providers should be able to recognize its protean manifestations.

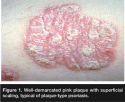

Typically, psoriasis is a chronic skin disorder characterized by well-demarcated round or oval erythematous, salmon pink papules and plaques, often with a superimposed silvery scale (see Figure 1). Psoriasis affects men and women equally; onset typically occurs in young adulthood, but the condition can manifest early or late in life. Lesions have a predilection for elbows, knees, scalp, face, gluteal cleft, and umbilicus; the condition also can present on genital skin, palms, soles, and elsewhere. Nail changes include pitting, subungual hyperkeratosis, onycholysis, and the “oil spot,” a pathognomonic finding of a tan-brown spot under the nail plate. These nail changes usually present after cutaneous disease, but may precede its occurrence. When the scale of an individual skin lesion is scraped, spots of punctate bleeding may develop, a phenomenon known as Auspitz’s sign.3

A variant presentation with an abrupt appearance of numerous small “drop-like” lesions is known as guttate psoriasis. Although guttate psoriasis may flare in patients with a history of classic psoriasis, it may occur in someone without such history, often in the setting of a streptococcal infection, such as pharyngitis. Appropriate antibiotic therapy targeted at streptococci may lead to skin improvement in this presentation.3

A variant presentation with an abrupt appearance of numerous small “drop-like” lesions is known as guttate psoriasis. Although guttate psoriasis may flare in patients with a history of classic psoriasis, it may occur in someone without such history, often in the setting of a streptococcal infection, such as pharyngitis. Appropriate antibiotic therapy targeted at streptococci may lead to skin improvement in this presentation.3

Inverse psoriasis, a form often misdiagnosed by nondermatologists, presents in intertriginous parts of the body, such as the inguinal, axillary, intergluteal, and inframammary areas. Scale often is absent and providers should consider this diagnosis if treatment for fungal or bacterial infection has not led to improvement.4

More severe forms of psoriasis can lead to serious morbidity and even mortality. Pustular psoriasis can present as an acute eruption of initially sterile “lakes of pus” with widespread erythema and scaling (see Figure 2). In addition to the pustules, the von Zumbusch variant also may present with fever, malaise, and leukocytois. Infection, pregnancy, and withdrawal of oral  corticosteroids may trigger pustular psoriasis. A less severe entity, pustulosis of the palms and soles, may cause tender pustules, often with bothersome fissuring.4

corticosteroids may trigger pustular psoriasis. A less severe entity, pustulosis of the palms and soles, may cause tender pustules, often with bothersome fissuring.4

Erythrodermic psoriasis, a rare manifestation, has been clinically observed to be acute or chronic, and may cause generalized, full body erythema (see Figure 3). Patients can develop complications from the loss of the integument, such as susceptibility to infection, as well as fluid and electrolyte disturbances.4

Commonly employed treatments for psoriasis are listed in Table 1.

In addition to its skin-associated complaints, psoriasis has been found to be associated with arthritis, depression, and lower quality of life.2,5-7 Recently, associations with certain cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, dyslipidemia, obesity, and elevations of C-reactive protein and hyperhomocysteinemia have led, in part, to patients with psoriasis having an increased risk of myocardial infarction and risk of death. At this point in time, there is only an epidemiologic association between psoriasis and cardiovascular risk, and causation is not conclusively known. Speculation surrounds the systemic inflammatory nature of psoriasis.8-10

Because dermatologists or primary care providers may be the only clinicians caring for a patient with psoriasis, they can play a pivotal role in identifying patients with psoriasis who are at risk for myocardial infarction and premature death. The purpose of this review is to alert clinicians caring for persons with psoriasis of this increased risk and remind them that they need to think about issues that extend beyond just the skin.

Association of Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Psoriasis

Several studies have found that numerous classic cardiovascular risk factors (such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, smoking, and dyslipidemia) are significantly more prevalent in patients with psoriasis than in the general population.11-20 Smoking, either current or past, was associated with an increased risk of incident psoriasis in the Nurses’ Health Study II11 that assessed more than 78,000 subjects (RR 1.78 for current smokers and 1.37 for past smokers). Smoking also was identified as an independent risk factor for psoriasis in a prospective cohort study12 with nested case-control analysis of nearly 4,000 patients in the United Kingdom General Practice Research Database. In a large, population-based, cross-sectional study, Niemann et al13 found significantly higher rates of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and smoking in more than 130,000 patients with psoriasis compared to those without psoriasis; also, persons with severe psoriasis had higher rates of obesity and diabetes than those with mild psoriasis. Similarly, another large case-control study14 found that patients with psoriasis, as well as persons with atherosclerosis, are at increased risk for developing diabetes mellitus compared to persons without psoriasis. This increased risk of atherosclerosis in psoriasis was further supported by the work of Gelfand et al,8 who found psoriasis (especially in persons affected at a young age with more severe disease) conferred an independent risk for myocardial infarction, which persisted even after controlling for traditional cardiovascular risk factors. This mounting evidence supports the association between psoriasis, cardiovascular risk factors, and myocardial infarction, making it essential for all physicians to be able to identify at-risk patients and determine when modifiable risk factors are not controlled optimally.

Potential Therapies for Specific Risk Factors

Obesity. Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30.0; overweight is defined as a BMI between 25.0 and 29.9. BMI is calculated by weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters and can be calculated online at: www.nhlbisupport.com/bmi/bmicalc.htm.

Obesity has well-known associations with diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, coronary heart disease, and stroke21; it is also associated with psoriasis.13,22 Because both obesity and being overweight have been associated with increased mortality independent of psoriasis,23 it is critical to address the higher prevalence of increased BMI in this at-risk population.

Obesity has well-known associations with diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, coronary heart disease, and stroke21; it is also associated with psoriasis.13,22 Because both obesity and being overweight have been associated with increased mortality independent of psoriasis,23 it is critical to address the higher prevalence of increased BMI in this at-risk population.

Treatment. Weight loss can be achieved successfully using nonpharmacologic, pharmacologic, and surgical options.24 Sibutramine and orlistat, both oral medications, can lead to modest weight loss. Sibutramine, a norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake-inhibitor, occasionally can induce elevations in blood pressure and pulse, insomnia, dry mouth, and constipation. Orlistat, an inhibitor of gut lipase that causes malabsorption of fat, can lead to greasy stools, flatulence, diarrhea, and anal leakage.25 Bariatric surgery is generally reserved for persons with a BMI >40 or persons with a BMI >35 with other risk factors.26 This approach has been shown in a retrospective study27 to lead not only to sustained weight loss, but also to a decrease in mortality in patients followed on average for 10.9 years.

Hypertension. Hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of >140/90 mm Hg, has been found to have a high prevalence in patients with psoriasis.8,13,15 Epidemiologic studies28 have shown the threshold for cardiovascular risk is blood pressures >115/75 mm Hg in all patients, doubling with each increment of 20/10 mm Hg. The higher the blood pressure, the greater the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and kidney failure.

Hypertension. Hypertension, defined as a blood pressure of >140/90 mm Hg, has been found to have a high prevalence in patients with psoriasis.8,13,15 Epidemiologic studies28 have shown the threshold for cardiovascular risk is blood pressures >115/75 mm Hg in all patients, doubling with each increment of 20/10 mm Hg. The higher the blood pressure, the greater the risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, and kidney failure.

Treatment. Treating hypertension has been found to lower the risk of heart failure by >50%, the risk of stroke by 35% to 40% and the risk of myocardial infarction by 20% to 25%.29 According to the Joint National Committee guidelines,30 treatment should be initiated when the blood pressure is ≥140/90 mm Hg for persons without diabetes and ≥130/80 for persons with diabetes or renal disease.31 Thiazide diuretics, alone or in combination with other anti-hypertensive medications, are preferred for most people with uncomplicated hypertension. For patients with high-risk comorbidities, other agents may be considered for initial therapy, such as beta-blockers (for those with coronary artery disease) or angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (for those with congestive heart failure or diabetes mellitus and proteinuria). Although retrospective studies28,32,33 have shown that beta-blockers are associated with the initiation or worsening of psoriasis, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and the thiazide diuretic, chlorthalidone, also have been associated with psoriasis.34-39

Diabetes mellitus. Diabetes mellitus, which is increasing in prevalence, has been associated with psoriasis.14,40,41 Diabetes is associated with microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy) and macrovascular (myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral arterial disease) complications. Treatment of diabetes mellitus has been found to reduce microvascular complications in both type I and type 2 diabetes,42-45 as well as myocardial infarction in persons with type 1 diabetes46; whether it decreases macrovascular complications in type 2 diabetes is a subject of investigation.47 Diabetes management includes diagnosis and maintaining the patient’s glycemic control at accepted targets.

According to the American Diabetes Association,48 diabetes is diagnosed by a repeatedly abnormal fasting glucose, an elevated nonfasting glucose level in the presence of symptoms, or an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test (see Table 1). Although hemoglobin A1c (a measure of glycemic control for the preceding 2 to 3 months) is not part of the diagnostic criteria, it is helpful in assessing overall glycemic control.

Treatment. In the absence of contraindications, the goal hemoglobin A1c for a diabetic patient is <7.0%.49 Medical management of diabetes mellitus is beyond the scope of this article; an excellent review of the subject has been published by Nathan et al.50

Smoking. In the US, tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death and is responsible for more than 400,000 deaths per year, nearly one in five of all deaths; approximately one half of all smokers die prematurely of diseases related to tobacco.51 Conversely, smoking cessation increases survival.52 Interestingly, studies11 have shown that patients who quit smoking for >20 years also reduced their risk for psoriasis.

Counseling and pharmacotherapy have been effective in improving rates of smoking cessation. Simply advising patients to quit increases smoking cessation rates by 30%.52 Brief counseling, even for fewer than 3 minutes, is more successful than simply advising a patient to quit and has been found to increase the cessation rate two-fold when compared to no intervention.53

Counseling and pharmacotherapy have been effective in improving rates of smoking cessation. Simply advising patients to quit increases smoking cessation rates by 30%.52 Brief counseling, even for fewer than 3 minutes, is more successful than simply advising a patient to quit and has been found to increase the cessation rate two-fold when compared to no intervention.53

Nicotine replacement (transdermal patches, gum, vapor inhaler, or nasal spray), the anti-depressant bupropion, and varenicline, the first new smoking cessation medication in nearly a decade, are effective pharmacologic therapies to help smokers quit tobacco use.53,54 Varenicline may lead to higher smoking cessation rates than bupropion,55 but it has been linked to the development or worsening of several psychiatric syndromes.56-58

The combination of counseling and pharmacotherapy may double the rate of smoking cessation seen with pharmacologic therapy alone.59 More than any other intervention, smoking cessation likely has the greatest impact on a patient’s overall health.

Dyslipidemia. Large epidemiological studies have demonstrated that elevated cholesterol levels increase cardiovascular risk and lowering cholesterol reduces this risk.60,61 Guidelines for optimal low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels are based on the patient’s underlying risk (see Table 2).62 For patients with no or one traditional cardiac risk factor, the goal LDL cholesterol is <160 mg/dL. For persons with more than one cardiac risk factor, the goal LDL cholesterol is <130 mg/dL. For patients with known vascular disease or a calculated Framingham 10-year risk of >20%, LDL targets are <100 mg/dL. An optional LDL goal of <70 mg/dL can be considered for patients at highest risk for myocardial infarction — ie, persons with known vascular disease and diabetes or an ongoing uncontrolled risk factor.63 The Framingham 10-year risk assessment can be calculated at: hp2010.nhlbihin.net/atpiii/calculator.asp?usertype=prof.

Treatment. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are preferred cholesterol-lowering agents. They appear to have added benefits, or pleitoropic effects, (ie, improvements in endothelial function and reduction of inflammatory markers) beyond the effect of lowering LDL levels. If their use is contraindicated, nicotinic acid, bile acid sequestrants, ezetimibe, or fibrates can be used.62 High-density lipoprotein (HDL) is protective against cardiovascular disease, but HDL increase has been found to be more amenable to dietary than to pharmacotherapeutic intervention than lowering the LDL.63

Aspirin use. Aspirin’s anti-platelet and anti-inflammatory properties64,65 have been shown to reduce recurrent cardiovascular events in persons with established cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease.66 Several studies67-70 also have evaluated the role of aspirin in primary prevention. The US Preventive Service Task Force71 found aspirin use decreases the risk of coronary heart disease in persons with increased risk, but at the cost of higher rates of gastrointestinal bleeding and fair consensus evidence of increases in hemorrhagic stroke. The researchers concluded aspirin should be used when the 5-year risk of coronary disease is 3% or greater, but only after discussing potential risks and benefits with the patient. The absolute risk of major coronary events can be calculated using the Framingham risk score.72,73 Aspirin also is recommended for patients with diabetes because they have similar cardiac risk as patients with established coronary artery or other vascular disease.65,74

Conclusion

Psoriasis is common and is associated with both cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular events independent of these risk factors, as well as premature mortality. The inflammatory milieu seen in this autoimmune process may account for the recently appreciated association between psoriasis, cardiovascular disease, and mortality. Clinicians caring for patients with psoriasis should recognize these cardiovascular risk factors and ensure they are being appropriately addressed and controlled. As with patients with traditionally known vascular disease risk factors, it is important to monitor and discuss patient weight, blood pressure, glycemic control, cholesterol level, and tobacco use, as well as aspirin usage. Dermatologists and primary care physicians have a unique opportunity to intervene by assessing these risk factors. By recognizing and treating these common comorbidities, clinicians may be able to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction and other potentially devastating complications. Future trials must assess the impact of interventions such as aspirin use and aggressive risk factor control in this population. Finally, it is possible, but yet unconfirmed, that treating severe psoriasis may reduce cardiovascular risk.75 If so, it would be extremely helpful to know whether the various systemic therapies for the treatment of severe psoriasis have differential impacts in reduction of cardiovascular risk in this vulnerable population.

1. National Psoriasis Foundation. Psoriasis statistics. Available at: www.psoriasis.org/about/stats . Accessed February 8, 2009.

2. Schon MP, Boehncke W-H. Psoriasis. New Engl J Med. 2005;352:1899–1912.

3. Holubar K, Fatovic-Ferencic S. Papillary tip bleeding or the Auspitz phenomenon: a hero wrongly credited and a misnomer resolved. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:263–264.

4. Van de Kerkhof P. Textbook of Psoriasis, 2nd Ed. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing;2003.

5. Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407.

6. Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T. The impact of psoriasis on quality of life. Results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:280–284.

7. Rapp SR, Exum ML, Reboussin DM, Feldman SR, Fleischer A, Clark A. The physical, psychological, and social impact of psoriasis. J Health Psychol. 1997;2:525–537.

8. Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA. 2006;296:1735–1741.

9. Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis. Results from a population-based study. Arch Derm. 2007;143:1493–1499.

10. Lebwohl M. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1197–1204.

11. Setty AR, Curhan G, Choi HK. Smoking and the risk of psoriasis in women: Nurses’ Health Study II. Am J Med. 2007;120:953–959.

12. Huerta C, Rivero E, Garcia Rodriguez LA. Incidence and risk factors for psoriasis in the general population. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1559–1565.

13. Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB, Gelfand JM. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:829–835.

14. Shapiro J, Cohen AD, David M, et al. The association between psoriasis, diabetes mellitus, and atherosclerosis in Israel: a case-control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:629–634.

15. Christophers E. Comorbidities in psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:52–55.

16. Henseler T, Christophers E. Disease concomitance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:982–986.

17. Mallbris L, Granath F, Hamsten A, Stahle M. Psoriasis is associated with lipid abnormalities at the onset of skin disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:614–621.

18. Rocha-Pereira P, Santos-Silva A, Rebelo I, Gigueiredo A, et al. Dislipidemia and oxidative stress in mild and in severe psoriasis as a risk for cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2001;303:33–39.

19. Sommer DM, Jenisch S, Suchan M, Christophers E, Weichental M. Increased prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;298:321–328.

20. Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Leffondre K, Sampogna F, Melchi F, et al. Relationship between smoking and the clinical severity of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1580–1584.

21. Haslam DW, James WPT. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366:1197–1209.

22. Li Z, Bowerman S, Heber D. Health ramifications of the obesity epidemic. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:681–701.

23. Herron MD, Hinckley M, Hoffman MS, et al. Impact of obesity and smoking on psoriasis presentation and management. Arch Derm. 2005;141:1527–1534.

24. Adams KF, Schatzkin A, Harris TB, et al. Overweight, obesity, and mortality in a large cohort of persons 50–71 years old. New Engl J Med. 2006;355:763–778.

25. Wyatt HR, Hill JO. What role for weight-loss medication? Weighing the pros and cons for obese patients. Postgrad Med. 2004;115:38–40.

26. Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Obesity. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:591–602.

27. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Am J Clin Nut. 1992;55(suppl 2):615S–619S.

28. Sjostrom J, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752.

29. Lewington S, Clark R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913.

30. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572.

31. Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman S. Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood pressure-lowering drugs. Lancet. 2000;356:1955–1964.

32. Tsankov N, Angelova I, Kazandjieva J. Drug-induced psoriasis. Recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:159–165.

33. Gold MH, Holy AK, Roenigk HH Jr. Beta-blocking drugs and psoriasis. A review of cutaneous side effects and retrospective analysis of their effects on psoriasis. J Amer Acad Dermatol. 1988;19:837–841.

34. Yilmaz MB, Turhan H, Akin Y, Kisacik HL, Korkmaz S. Beta-blocker-induced psoriasis: a rare side effect-a case report. Angiology. 2002;53:737–739.

35. Dika E, Bardazzi F, Balestri R, Maibach HI. Environmental factors and psoriasis. Curr Problems Dermatol. 2007;35:118–135.

36. Cohen AD, Bonneh DY, Reuveni H, et al. Drug exposure and psoriasis vulgaris: case control and case cross-over studies. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2005;85:299–303.

37. Wolf R, Dorfman B, Krakowski A. Psoriasiform eruption induced by captopril and chlorthalidone. Cutis. 1987;40:162–164.

38. Antonov D, Grozdev I, Pehlivanov G, Tsankov N. Psoriatic erythroderma associated with enalapril. SKINmed. 2006;5:90–92.

39. Kawamura A, Ochiai T. Candesartan cilextil induced pustular psoriasis. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:406–407.

40. Marquart-Elbaz C, Grosshans E, Lipsker D, Lipsker D. Sartans, angiotensin II receptor antagonists can induce psoriasis. Brit J Dermatol. 2002;147:617–618.

41. Hagforsen E, Michaelsson K, Lundgren E, et al. Women with palmopustular psoriasis have disturbed calcium homeostasis and a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and psychiatric disorders: a case-control study. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2005;85:225–232.

42. Binazzi M, Calandra P, Lisi P. Statistical association between psoriasis and diabetes: further results. Arch Dermatol Res. 1975;254:43–48.

43. Diabetes Control and Complications Research Group. The effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. New Engl J Med. 1993;329 978–986.

44. Reichard P, Nilsson B-Y, Rosenqvist U. The effect of long-term intensified insulin treatment on the development of microvascular complications of diabetes mellitus. New Engl J Med. 1993;329:304–309.

45. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complication in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–853.

46. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive glucose control with metformin on complication in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS34). Lancet. 1998;352:854–865.

47. Diabetes Control and Complications Group/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. New Engl J Med. 2005;353:2643–2653.

48. Bastien A. The ACCORD trial: a multidisciplinary approach to control cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Practical Diabetol. 2004;23:6–11.

49. Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160–3167.

50. Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy. A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:1963–1972.

51. Tobacco Use-United States, 1990-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:986–993.

52. Department of Health and Human Services. The health benefits of smoking cessation: a report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1990. DHHS Publication no. (CDC) 90-8416.

53. Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence, Rockville, Md: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service 2000.

54. Rigotti NA. Treatment of tobacco use and dependence. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:506–512.

55. Glover ED, Rath JM. Varenicline: progress in smoking cessation treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8:1757–1767.

56. Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, et al. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7 week, randomized, placebo- and buproprion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Int Med. 2006;166:1561–1568.

57. Kohen I, Kremen N. Varenicline-induced manic episode in a patient with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1269–1270.

58. Freedman R. Exacerbation of schizophrenia by varenicline. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:269.

59. Hughes JR, Goldstein MG, Hurt RD, Schiffman S. Recent advances in the pharmacotherapy of smoking. JAMA. 1999;281:72–76.

60. Chen Z, Peto R, Collins R, et al. Serum cholesterol concentration and coronary heart disease in population with low cholesterol concentrations. BMJ. 1991;303:276–282.

61. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;356:1267–1278.

62. Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497.

63. Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz NB, et al. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Panel III Guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239.

64. Ridker PM, Cushman M, Stampfer MJ, Tracy RP, Hennekens CH. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of coronary heart disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–979.

65. Stampfer MJ, Jakubowski JA, Deykin D, Shafer AI, et al. Effect of alternate-day regular and enteric-coated aspirin on platelet aggregation, bleeding time and thromboxane A2 levels in bleeding-time blood. Am J Med. 1986;81:400–404.

66. Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trial of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high-risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71–86.

67. Peto R, Gray R, Collins R, et al. Randomised trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296:313–316.

68. The Medical Research Counsel’s General Practice Research Framework. Thrombosis prevention trial: randomized trial of low-intensity oral anticoagulation and low-dose aspirin in the prevention of ischaemic heart disease in men at increased risk. Lancet. 1998;351:233–241.

69. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al. Effects of intensive blood pressure-lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomized trial. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762.

70. Collaborative Group of the Primary Prevention Project. Low-dose aspirin and vitamin E in people at cardiovascular risk: a randomized trial in general practice. Lancet. 2001;357:89–95.

71. Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: recommendation and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:157–160.

72. D’Agostino RB Sr, Grunds S, Sullivan LM, Wilson P. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–187.

73. Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97:1837–1847.

74. Lauer MS. Aspirin for primary prevention for coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1468–1474.

75. Prodanovich S, Ma F, Taylor JR, Pezon C, Fasihi T, Kirsner RS. Methotrexate reduces incidence of vascular diseases in veterans with psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:262–267.