Nutrition 411: Iron Deficiency

Patients often complain about fatigue and tiredness. Some might even say, “Maybe I am low on iron.” What they are suggesting is the presence of iron deficiency anemia, which occurs when iron is sufficiently deficient to diminish erythropoiesis and cause the development of anemia. This may, in fact, be the source of the problem because iron is the nutrient most commonly deficient — approximately 40% of the total world population is affected.1 Because there are many other types of anemia — eg, pernicious anemia, anemia of chronic disease, hemolytic anemia, and megaloblastic anemia — it is important to be able to distinguish one type from another. Treatment interventions may vary depending on the type of anemia and the source of the problem. In this article, we take a closer look at iron deficiency anemia.

Functions of Iron

Iron is the fourth most abundant element in the earth’s crust yet it is only a trace element in the human body. Although iron makes up only 0.0004% of the human body’s mass, it is an essential component or cofactor of numerous metabolic reactions.2 Iron has many functions in the body — perhaps the most important as a component of a protein called heme. Iron is necessary to manufacture hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen from the lungs to the body’s tissues and what gives blood its usual red color. Iron also plays a role in immune function, cognitive status, and many other processes including the synthesis of DNA, collagen, and bile acids.

Iron Deficiency

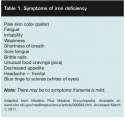

The term anemia is used to describe many conditions where red blood cells are not providing adequate oxygen to body tissues. The most common type and cause of anemia is iron deficiency anemia — ie, a decrease in the number of red cells in the blood caused by too little iron. In other words, when too little iron is available to produce an adequate amount of hemoglobin, anemia results. Iron deficiency anemia has many causes, including too little iron in the diet, poor iron absorption, and iron depleted by blood loss due to gastrointestinal bleeding related to ulcers, heavy menstrual bleeding, and certain types of cancers, particularly in the stomach, colon, or esophagus. Table 1 lists the symptoms of iron deficiency. It is important to note that in mild cases of deficiency, no symptoms may be present.

Diagnosing Iron Deficiency Anemia

The first step in any diagnosis is a thorough history and physical. The clinician should ask about blood loss, medications such as extended NSAID use, family history of anemia, any fatigue-related lifestyle changes, and dietary and supplement intake. If anemia is suspected, the physical exam should note any splenomegaly, blood in the stool, pallor, and other physical symptoms as listed in Table 1. A complete blood count (CBC) should be performed. The laboratory diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia includes:

•Low hemoglobin (Hgb) and hematocrit (Hct)

•Small red blood cells (microcytic cells)

•Low serum ferritin

•Low serum iron

•High iron-binding capacity (TIBC)

•Blood in the stool (visible or microcytic).

Many practitioners only assess Hgb and Hct, but it is important to remember that iron deficiency occurs in stages and Hgb and Hct may remain normal until well into the cycle of iron depletion. In the early stage, iron stores are depleted and ferritin levels are decreased. Hgb and Hct may still be normal in this stage. As the depletion of iron progresses, transferrin levels rise and serum iron levels fall. If the depletion continues over time, normocytic, normochromic anemia occurs. The final stage is the development of microcytic, hypochromic anemia.

The degree of decrease in Hgb and Hct depends on the length of time the bone marrow has been without sufficient supplies of iron. Other indicators on the CBC also should be reviewed, including mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH), and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC). The MCV measures the mean or average size of individual red blood cells. In iron deficiency, the MCV is low, indicating the cells are microcytic.3 The MCH measures the amount of hemoglobin present in one red blood cell. The MCHC measures the proportion of each cell taken up by hemoglobin3; results are reported in percentages, reflecting the proportion of hemoglobin in the red blood cells. The MCV, MCH, and MCHC all are decreased in iron deficiency anemia. MCHC is the last to be affected. This is due to the fact that as the marrow becomes more and more depleted of iron, it produces smaller cells with a smaller amount of hemoglobin in each cell in an attempt to keep the concentration of hemoglobin normal.3 A growing body of evidence supports using serum ferritin as an initial indicator of iron deficiency. If iron deficiency is suspected, it may be worthwhile to request a serum ferritin level to supplement the CBC.

Treatment

Iron deficiency treatment is dependent on the cause. For example, if the cause is blood loss, the source of blood loss must be identified and corrected. In many elderly and patients residing in long-term care facilities, the cause of anemia often involves poor food intake and poor absorption. Many institutionalized patients have less-than-optimal meal consumption and are not eating foods high in iron. These foods include liver, eggs, kidney, beef, dried fruits, enriched whole grain cereals, enriched flour, lentils, molasses, and oysters. To compound the problem, many of these foods are not typically found on healthcare menus.

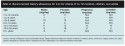

For practical purposes, the best food choices for iron are enriched products and meats. Fortified ready-to-eat cereals usually contain at least 25% of the US recommended daily allowance (RDA) for iron. Table 2 outlines the iron requirements for various age groups.

Iron is found in the diet in two forms — heme iron, which is well absorbed, and non-heme iron, which is poorly absorbed. Vitamin C enhances the absorption of non-heme iron from the intestine, so it may be helpful to combine foods with iron and vitamin C to increase the amount of iron absorbed. For example, a recommended nutritional intervention is to serve orange juice with meals to increase absorption of non-heme iron. Citrus fruits are well-known for their vitamin C content; many vegetables such as tomatoes, cauliflower, broccoli, and potatoes are also a good source of vitamin C and can be utilized to increase absorption.

Iron is found in the diet in two forms — heme iron, which is well absorbed, and non-heme iron, which is poorly absorbed. Vitamin C enhances the absorption of non-heme iron from the intestine, so it may be helpful to combine foods with iron and vitamin C to increase the amount of iron absorbed. For example, a recommended nutritional intervention is to serve orange juice with meals to increase absorption of non-heme iron. Citrus fruits are well-known for their vitamin C content; many vegetables such as tomatoes, cauliflower, broccoli, and potatoes are also a good source of vitamin C and can be utilized to increase absorption.

Iron supplements. The issue of iron supplementation should be approached cautiously. Many patients take a daily multivitamin, which typically contains 18 mg of iron. Additional iron supplements should be prescribed only if the anemia has been conclusively defined as iron deficiency. A serum ferritin level <15 micrograms per liter confirms iron deficiency anemia in women and suggests a possible need for iron supplementation.4 For adults who are not pregnant, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends taking 50 mg to 60 mg of oral elemental iron (the approximate amount of elemental iron in one 300-mg tablet of ferrous sulfate) twice daily for 3 months for the therapeutic treatment of iron deficiency anemia.5 However, physicians should evaluate each person individually and prescribe according to individual needs.

Iron supplements may cause side effects such as constipation, black stools, diarrhea, nausea, and leg cramps. Many patients may find iron very difficult to tolerate. Enteric coated supplements may be easier to tolerate but they are not recommended because they may not be adequately absorbed.6 Liquid iron tends to stain the teeth so it is best to mix it with juice and use a straw.

Many brands and forms of iron supplements, including ferrous and ferric, are available today, and one type may agree with a patient better than another. Ferrous iron salts (ferrous fumarate, ferrous sulfate, and ferrous gluconate) are the best absorbed forms of iron supplements.6 Advising the patient to take iron supplements with meals may help with any gastrointestinal issues. Other tips are to begin with a half-dose and build up to the full dose and to take iron in divided doses throughout the day. If a deficiency cannot be corrected with oral supplements due to tolerance or other problems, a variety of intravenous iron preparations are available.

Practice Points

In wound healing, collagen synthesis requires the hydroxylation of lysine and proline, which utilize several cofactors, including ferrous iron and vitamin C. Impaired wound healing results from deficiencies of any of these cofactors.7 Treating iron deficiency anemia takes a team approach; each discipline has something to offer. The nursing staff may be the first to identify low levels of Hgb and Hct on the lab reports and notify the physician. The physician may order additional tests, multivitamins, or supplements. The registered dietitian (RD) should monitor oral intake and recommend appropriate food choices and tips such as using vitamin C to increase absorption. The pharmacist should monitor for any food or drug interactions and can suggest different brand and forms of iron if tolerance problems occur. It is a myth that anemia is a normal part of aging and is simply something to expect and accept. With a little attention and knowledge, we can keep pumping the iron.

Nancy Collins, PhD, RD, LD/N, FAPWCA, is founder and executive director of RD411.com and Wounds411.com. For the past 20 years, she has served as a consultant to healthcare institutions and as a medico-legal expert to law firms involved in healthcare litigation. Correspondence may be sent to Dr. Collins at NCtheRD@aol.com. This article was not subject to the Ostomy Wound Management peer-review process.

Coming next month: urinary tract infections and cranberry research.

1. Escott-Stump S. Nutrition and Diagnosis-Related Care, 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins;2002:472.

2. Uthman E. Nutritional Anemias. Available at: http://web2.iadfw.net/uthman/nutritional_anemia/nutritional_anemia.html. Accessed March 7, 2011.

3. Kennedy R. The Doctor’s Medical Library. Red Blood Cells. Available at: www.medical-library.net/cbc_red_blood_cells.html. Accessed March 7, 2011.

4. Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-3):1–29.

5. National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary Fact Sheet: Iron. Available at http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/iron. Accessed March 7, 2011.

6. Brittenham GM.Disorders of iron metabolism: iron deficiency and overload. In: Hoffman R, Furie B, Benz EJ Jr, et al. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice, 3rd ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone, Harcourt Brace & Co;2000.

7. Campos AC, Groth AK, Branco AB. Assessment and nutritional aspects of wound healing. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metabol Care. 2008;11(3):281–288