An E-Learning Program to Prevent Pressure Ulcers in Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: A Pre- and Post- Pilot Test Among Rehabilitation Patients Following Discharge to Home

Abstract

Pressure ulcers (PrUs) are the most common medical complication following spinal cord injury (SCI), as well as costly and potentially life-threatening. Every individual with SCI is at life-long risk for developing PrUs, yet many lack access to readily available, understandable, and effective PrU prevention strategies and practices.

To address barriers to adequate PrU prevention education, an interactive e-learning program to educate adults with SCI about PrU prevention and management was developed and previously pilot-tested among inpatients. This recent pilot study was conducted to evaluate the feasibility of using the learning portion of the program by adults with SCI following discharge to home among 15 outpatients with SCI. Fourteen patients (nine men, five women, median age 37 years) completed the program intervention and pre- and follow-up questionnaires. The median score for pre-program knowledge and skin care management practice was 96 (possible score: 0 to 120; range 70–100). Post-program use median score was 107 (range 97–114). The greatest improvement was in the responses to knowledge and practice questions about skin checks and preventing skin problems (P <0.005). In terms of their experiences and perceptions, the program was well received by the study participants. Further evaluation involving large samples is necessary to confirm these findings and ascertain the effect of this e-learning program on PrU incidence. Internet interventions that are proven effective hold tremendous potential for bringing prevention education to groups who would otherwise not receive it.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: This project was funded in part by a grant from the Paralyzed Veterans of America Education Foundation (Principal Investigator: J. Schubart).

Introduction

Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) has a profound impact on individuals and their family members. SCI produces immediate physiologic and functional changes and usually results in mild to severe paralysis and loss of sensation below the level of injury.1-6 Pressure ulcers (PrUs) are the most common medical complication following SCI; they are costly1,7 and potentially life-threatening.2 Every individual with SCI is at life-long risk for developing PrUs,8 a risk that increases with age1,9; 25% to 30% of individuals with SCI will have at least one PrU within the first 5 years after injury, and as many as 80% may experience PrUs that require medical intervention throughout their lives.2,10,11 General risk factors for PrUs include inability to shift weight to relieve pressure, moist skin, poor nutrition, illnesses, and smoking.2

Structured, face-to-face education programs delivered to adults with SCI by healthcare providers have been shown to be effective in increasing knowledge and reducing development or recurrence of PrUs.5,12-14 Although PrU prevention through routine health maintenance has been widely reported in observational and experimental studies,1,3-5,12,15-17 a systematic review18 has shown many people with SCI lack access to readily available, understandable, and clear PrU prevention and management strategies and practices. Resources in hospitals and rehabilitation centers to provide prevention education to adults with SCI and their family caregivers are often inadequate, at least partly due to the shortened length of stay in such facilities post SCI.19 Additionally, face-to-face PrU prevention education is expensive to deliver in terms of caregiver time and may not be timed to be most effective.20

Few studies measure long-term knowledge outcomes, and the results are inconsistent. For example, Garber et al12 conducted a randomized, controlled trail (RCT) among 41 male veterans where the intervention group received an additional 4 hours (above standard care) of individualized, structured education on the prevention and management of PrUs near the end of their hospital stay. Although the trial was stopped early (due to failure to reach the endpoint of PrU recurrence), the researchers reported that most participants retained prevention knowledge up to 24 months post-discharge. In contrast, Thietje et al21 report that among 214 hospitalized patients with SCI, <50% had good knowledge about PrUs 30 months after discharge.

This author has observed that PrU prevention education in hospital and rehabilitation settings often is offered in the early stages of rehabilitation, before patients and family caregivers fully understand their own education needs for living at home. Individuals with SCI may find that education and information needs emerge over time along with the condition of their SCI; as such, patients may not be likely to know all their information and education needs when they are in the hospital, rehabilitation center, or physician’s office.  Health education programs may help provide critical information and behavioral prescriptions to patients and their caregivers, although researchers have long recognized the difficulty in eliciting sustained learner behavior change and adherence to prescribed health regimens.22 Effective health education programs go beyond information needs and include behavioral skills practice and mastery, as well as opportunities for feedback and reinforcement.12 Social cognitive theory grounds many models of prevention intervention in its emphasis on observation, modeling, and behavioral rehearsal. Accurately assessing the needs of learners and taking into account their prior knowledge has been shown in studies using observational and experimental design evaluation research techniques to increase the effectiveness of an education program.23-25 Materials can be made relevant to the unique needs of learners by setting appropriate, measurable objectives,26 involving the learners in hands-on practice of behaviors and skills,27-29 and assessing learners in an authentic and meaningful way.30,31 Social learning theory posits that modeling and behavioral rehearsal result in increased positive outcome expectancies, increased self efficacy, and increased probability of receiving reinforcement for initial behavioral changes.32,33

Health education programs may help provide critical information and behavioral prescriptions to patients and their caregivers, although researchers have long recognized the difficulty in eliciting sustained learner behavior change and adherence to prescribed health regimens.22 Effective health education programs go beyond information needs and include behavioral skills practice and mastery, as well as opportunities for feedback and reinforcement.12 Social cognitive theory grounds many models of prevention intervention in its emphasis on observation, modeling, and behavioral rehearsal. Accurately assessing the needs of learners and taking into account their prior knowledge has been shown in studies using observational and experimental design evaluation research techniques to increase the effectiveness of an education program.23-25 Materials can be made relevant to the unique needs of learners by setting appropriate, measurable objectives,26 involving the learners in hands-on practice of behaviors and skills,27-29 and assessing learners in an authentic and meaningful way.30,31 Social learning theory posits that modeling and behavioral rehearsal result in increased positive outcome expectancies, increased self efficacy, and increased probability of receiving reinforcement for initial behavioral changes.32,33

Health-related behavioral programs based on social cognitive theory generally target four interactive determinants of behavior.34 First, behavior change requires accurate information to increase awareness and knowledge of risks. Second, preventive behavior change requires skills and self-efficacy — that is, believing not only that behavior change will lead to desired results, but also believing that one has the ability to adhere to preventive behaviors. Third, individuals must possess social and self-management skills for effective implementation. Fourth, and critical to success, behavior change involves creating social supports and positive reinforcement for change.32-35 Spanning both the cognitive and behavioral frameworks, social cognitive theory encompasses attention, memory, and motivation.36

To address the barriers to adequate PrU prevention education, an interactive e-learning program to educate adults with SCI about PrU prevention and management was developed37 and tested.37,38 The e-learning program combines traditional cognitive-domain learning strategies with a case-based format to provide a real-world learning environment tailored to the problems and situations encountered by people with SCI in preventing and managing PrUs in daily life. The program was shown previously to increase PrU knowledge in a small sample of hospitalized patients who used the program38; however, testing is needed in larger and diverse patient and community populations.

To address the barriers to adequate PrU prevention education, an interactive e-learning program to educate adults with SCI about PrU prevention and management was developed37 and tested.37,38 The e-learning program combines traditional cognitive-domain learning strategies with a case-based format to provide a real-world learning environment tailored to the problems and situations encountered by people with SCI in preventing and managing PrUs in daily life. The program was shown previously to increase PrU knowledge in a small sample of hospitalized patients who used the program38; however, testing is needed in larger and diverse patient and community populations.

The design of the e-learning program described and tested in this pilot study is consistent with the literature to date suggesting that PrU prevention education and treatment should include a behavioral component aimed at improving skin care behaviors.39 Few experimental design studies assess the impact of PrU education programs; however, a small RCT40 (n = 41) testing enhanced education and telephone follow-up in surgical patients treated for PrUs reported positive results. Although much is known about PrUs and prevention methods, little is known about why some patients do not practice optimal skin care and PrU prevention strategies.16 As noted by an invited panel of experts addressing critical knowledge gaps in PrUs in individuals with SCI in 2009, “… appropriate educational programs, which empower patients to take responsibility for skin care, are valuable for decreasing recurrence; however, research is needed to determine which approaches work best for different populations of individuals with SCI”.41 The purpose of this prospective pilot study was to test the feasibility of the e-learning program among adults with SCI discharged to home from a rehabilitation hospital setting.

The design of the e-learning program described and tested in this pilot study is consistent with the literature to date suggesting that PrU prevention education and treatment should include a behavioral component aimed at improving skin care behaviors.39 Few experimental design studies assess the impact of PrU education programs; however, a small RCT40 (n = 41) testing enhanced education and telephone follow-up in surgical patients treated for PrUs reported positive results. Although much is known about PrUs and prevention methods, little is known about why some patients do not practice optimal skin care and PrU prevention strategies.16 As noted by an invited panel of experts addressing critical knowledge gaps in PrUs in individuals with SCI in 2009, “… appropriate educational programs, which empower patients to take responsibility for skin care, are valuable for decreasing recurrence; however, research is needed to determine which approaches work best for different populations of individuals with SCI”.41 The purpose of this prospective pilot study was to test the feasibility of the e-learning program among adults with SCI discharged to home from a rehabilitation hospital setting.

E-learning Program Development

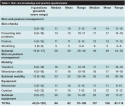

Needs assessment. To ensure the web-based program targeted the needs of adults with SCI, an environmental assessment of educational needs of people with SCI in preventing and managing PrUs was conducted (see Figure 1).37 Using a qualitative design, educational needs were assessed by interviewing adults with SCI and their caregivers, physical and occupational therapists, and physicians and nurses treating adults with SCI and PrUs. In addition, 65 adults with SCI and caregivers completed an online survey. Participants included seven women and nine men representing a diverse group in terms of age (mid-twenties to 50 years), time since injury (<1 year to 33 years), and PrU experience (10 had a prior and 10 had a current PrU). Analysis of their survey questionnaire responses and the transcribed interviews revealed critical educational needs common to persons with SCI regarding maintaining skin health and preventing and managing a PrU (see Table 1).

E-learning program development. Development methodology combined a unified instructional design framework for health education42 with a set of theory-driven instructional strategies for health education.43-47 The resulting Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program is an interactive learning experience situated within the authentic environment faced by adults with SCI. To ensure the design of the intervention met the performance requirements and to create a streamlined programming environment, an iterative design approach was used that produced successive approximations of the end product (see Figure 2). The e-learning program was developed in a modularized format and based on a tested theoretical Internet model.48 This format allows for altering the content, the order of content, and delivery approach to provide flexibility.49 Figure 3 shows the program introduction screenshot. The Learning section (see Figure 4) answers basic questions about PrUs and PrU prevention (ie, risk factors, healthy skin strategies, and related concerns). The Living section is an interactive case study, which distills the challenges people face when they get a PrU. The Looking section contains a glossary of the key information contained in the program. The program is self-paced and interactive; users are prompted to enter personal data to see a visual representation of their own risk (see Figure 5). The first implementation of the Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program was in a prospective study38 of 18 hospitalized patients with SCI. Sixteen patients showed improvement in pre-post knowledge tests, suggesting that a single viewing improved SCI patient knowledge of PrU assessment and prevention, regardless of age, educational level, or length of time with an SCI.

E-learning program development. Development methodology combined a unified instructional design framework for health education42 with a set of theory-driven instructional strategies for health education.43-47 The resulting Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program is an interactive learning experience situated within the authentic environment faced by adults with SCI. To ensure the design of the intervention met the performance requirements and to create a streamlined programming environment, an iterative design approach was used that produced successive approximations of the end product (see Figure 2). The e-learning program was developed in a modularized format and based on a tested theoretical Internet model.48 This format allows for altering the content, the order of content, and delivery approach to provide flexibility.49 Figure 3 shows the program introduction screenshot. The Learning section (see Figure 4) answers basic questions about PrUs and PrU prevention (ie, risk factors, healthy skin strategies, and related concerns). The Living section is an interactive case study, which distills the challenges people face when they get a PrU. The Looking section contains a glossary of the key information contained in the program. The program is self-paced and interactive; users are prompted to enter personal data to see a visual representation of their own risk (see Figure 5). The first implementation of the Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program was in a prospective study38 of 18 hospitalized patients with SCI. Sixteen patients showed improvement in pre-post knowledge tests, suggesting that a single viewing improved SCI patient knowledge of PrU assessment and prevention, regardless of age, educational level, or length of time with an SCI.

Program Evaluation in Rehabilitation Patients Discharged to Home

The purpose of this pilot study was to evaluate the Learning section of the Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program among SCI patients in the community by examining participants’ experiences and perceptions. The study was conducted over a 6-month period in 2010. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Penn State University, and all participants used the program from their homes and completed the post-test questionnaire by telephone.

Participants. Patients who were outpatients at the Penn State University Hospital’s Rehabilitation Center were invited to participate. Patients with an SCI at any level, age 18 or older, and the ability to access the Internet (in order to complete the program over a 2-week period) were eligible to participate. Exclusion criteria included non-English speaking patients and medically unstable SCI patients. There were no other inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Measures. Questions were used from three related instruments to assess the e-learning program: Internet Evaluation and Utility Questionnaire, Internet Impact and Effectiveness Questionnaire, and Internet Adherence Questionnaire.50,51 These validated instruments assess experiences and perceptions associated with an Internet intervention using 5-point Likert scales, combined with open-ended items asking participants to identify the most and least helpful parts of the program. The constructs under Evaluation and Utility include ease of use, convenience, engagement, enjoyment, layout, privacy, satisfaction, and acceptability. The Impact and Effectiveness constructs measure perceptions of the program material in terms of usefulness, comprehension, credibility, likelihood of returning, mode of delivery, and helpfulness. Adherence measures barriers to using the e-learning program.

Measures. Questions were used from three related instruments to assess the e-learning program: Internet Evaluation and Utility Questionnaire, Internet Impact and Effectiveness Questionnaire, and Internet Adherence Questionnaire.50,51 These validated instruments assess experiences and perceptions associated with an Internet intervention using 5-point Likert scales, combined with open-ended items asking participants to identify the most and least helpful parts of the program. The constructs under Evaluation and Utility include ease of use, convenience, engagement, enjoyment, layout, privacy, satisfaction, and acceptability. The Impact and Effectiveness constructs measure perceptions of the program material in terms of usefulness, comprehension, credibility, likelihood of returning, mode of delivery, and helpfulness. Adherence measures barriers to using the e-learning program.

In the second part of the assessment, to test knowledge acquired, an instrument based on the Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC),52,53 a brief structured interview tool was used to assess skin and posture management (19 questions), mobility and transfers (12 questions), and wheelchair/equipment (nine questions) (see Table 2). A total score was calculated by summing accurate responses. Sample items include: Do you (instruct others to) check your skin? Can you (instruct others to) maintain a full range of movements in all your joints by stretching? Do you (instruct others to) inspect your cushion for sign of wear and tear? Possible scores for the adapted NAC could range from 0 to 120, with higher scores reflecting higher knowledge and skin care management behaviors.

In the second part of the assessment, to test knowledge acquired, an instrument based on the Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC),52,53 a brief structured interview tool was used to assess skin and posture management (19 questions), mobility and transfers (12 questions), and wheelchair/equipment (nine questions) (see Table 2). A total score was calculated by summing accurate responses. Sample items include: Do you (instruct others to) check your skin? Can you (instruct others to) maintain a full range of movements in all your joints by stretching? Do you (instruct others to) inspect your cushion for sign of wear and tear? Possible scores for the adapted NAC could range from 0 to 120, with higher scores reflecting higher knowledge and skin care management behaviors.

Procedure. A rehabilitation clinic nurse approached English-speaking patients with SCI who met inclusion criteria during outpatient visits and briefly described the study. Interested patients were invited to participate, the purpose of the study was explained, questions were answered, and informed written consent was obtained before any data were collected. A nurse administered the NAC to all participants individually. After completing the questionnaire, participants were sent an email with a link to access the e-learning program.

Post-intervention questionnaires were administered in a telephone interview after the participant had completed the Learning section of the program. The set of knowledge questions was the same. The Internet Evaluation and Utility Questionnaire was administered post-intervention only. The researcher was available to answer questions during the study by telephone or email. This ensured each participant was able to use the program without technical difficulties. Participants could opt to complete the program in multiple sittings, starting where they left off, over a 2-week time frame. Data entry was completed by a study assistant. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA) and analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (Cary, NC) with statistical tests for nonparametric, two dependent samples of ordinal data.

Results

Fifteen participants (10 men, five women; median age 37 years) out of 24 invited provided informed consent and enrolled in the pilot test study of the Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program. One participant withdrew from the study; he used the program, but chose not to complete the post-intervention assessment when telephoned by the researcher. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 3.  Of the 14 participants who completed the assessment questionnaire post-intervention, in response to the question, “How easy was the web program to use?” all indicated the program was “mostly” or “very” easy to use (ratings of 3 or 4 on the 0-4 Likert scale, respectively). In response to the questions, “How easy was the information to understand in the web program?” and “How useful did you find the information in the web program?” all indicated the information in the program was understandable and useful (ratings of 4). In response to, “How good of a method was the Internet for delivering this treatment?” two of the 14 said “mostly” and 12 said “very” (see Table 4).

Of the 14 participants who completed the assessment questionnaire post-intervention, in response to the question, “How easy was the web program to use?” all indicated the program was “mostly” or “very” easy to use (ratings of 3 or 4 on the 0-4 Likert scale, respectively). In response to the questions, “How easy was the information to understand in the web program?” and “How useful did you find the information in the web program?” all indicated the information in the program was understandable and useful (ratings of 4). In response to, “How good of a method was the Internet for delivering this treatment?” two of the 14 said “mostly” and 12 said “very” (see Table 4).

In terms of program impact, 11 participants reported the program increased their knowledge about PrUs. In response to the question, “How much did the web program help you feel more confident in your ability to prevent and/or detect PrUs?” four said “mostly” and 10 said “very”. When asked how well they were able to follow through with the program recommendations, two reported “slightly,”10 reported “somewhat,” and two reported “mostly” or “very” able. Problems with computers or Internet connections did not interfere with program adherence. Having time in their schedule was “a little problem” for three participants, and three participants expressed concern that the program would take too long to complete. Eight participants completed the self-paced program in more than one session (sitting); the average time per sitting reported by participants was approximately 45 minutes.

Participants completed the Skin Care Knowledge and Practice Questionnaire before and after they used the web-based program. Pre- and post-test results are reported in Table 5. From baseline (pre-test) to post-test, median and mean total scores increased from 96 and 92, respectively, to 107 and 106 (possible score range 0 to 120), and the range of total scores increased from 70 to 100 to 97 to 114. The greatest improvement was in the responses to questions about skin checks and preventing skin problems (subscale scores reached statistical significance at P <0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test). Other findings were not significant. Pre-test responses to questions about mobility and equipment were high; specifically, the median and mean subtotals for mobility were 33 and 32 (possible score range 0 to 36), respectively, and the median and mean subtotals for equipment were both 20 (possible score range 0 to 27) and remained stable at post-test. In this small, diverse sample it was not possible to correlate scores to demographic variables.

Participants completed the Skin Care Knowledge and Practice Questionnaire before and after they used the web-based program. Pre- and post-test results are reported in Table 5. From baseline (pre-test) to post-test, median and mean total scores increased from 96 and 92, respectively, to 107 and 106 (possible score range 0 to 120), and the range of total scores increased from 70 to 100 to 97 to 114. The greatest improvement was in the responses to questions about skin checks and preventing skin problems (subscale scores reached statistical significance at P <0.05, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test). Other findings were not significant. Pre-test responses to questions about mobility and equipment were high; specifically, the median and mean subtotals for mobility were 33 and 32 (possible score range 0 to 36), respectively, and the median and mean subtotals for equipment were both 20 (possible score range 0 to 27) and remained stable at post-test. In this small, diverse sample it was not possible to correlate scores to demographic variables.

Discussion

This e-learning program is an example of using technology to increase access to care for adults with SCI by offering a method of prevention education not restricted by geographical location or provider or insurance availability. This pilot study assessed use of the Pressure Ulcer Prevention and Management E-Learning Program by rehabilitation patients who used the program in their homes. Overall, the program was well received by participants, and their knowledge and practice scores related to PrU skin care prevention increased. In addition, the responses to the five questions related to the program’s impact and effectiveness are especially encouraging. Participants reported an increase in their knowledge and confidence in their ability to prevent and detect PrUs; also, they were likely to recommend the program to others. On the other hand, responses to the question concerning how well they followed through with program recommendations were not as high (nine indicated “somewhat”), reflecting a need to follow participants for a longer time period.

As Internet interventions48,54 and PrU prevention programs are validated, more people will be able to access and utilize them. In many studies, people with SCI report substantial use of the Internet for obtaining health information55,56; however, findings regarding Internet use by people with SCI are inconsistent. For example, in a survey of 207 individuals with SCI living in a community setting, Burkell et al57 reported that one third of SCI study participants used the Internet for SCI information; the Internet also was rated as the most accessible and least reliable source of information; interpersonal sources (SCI specialists and healthcare professionals) were preferred. Internet programs developed by therapists, physicians, and nurses treating adults with SCI and PrUs, and then validated, could be used in rehabilitation settings and/or prescribed for home use after discharge. Because time spent in rehabilitation facilities has shortened, patients and family members have less time to absorb self-care information while in the hospital and, therefore, will need to be proactive in knowledge acquisition after discharge. Low-cost preventative approaches such as Internet programs are needed, yet few have been identified, although an alternative approach, a telephone calling system developed by Houlihan et al,58 also has shown promising results in preliminary testing. Internet “interventions” can mediate some of the barriers associated with traditional face-to-face prevention education, including expense, waiting time for appointments, and travel time to specialty rehabilitation and care clinics. Internet interventions can make prevention education available when and where the patient chooses.

Limitations

This pilot test was a small single site study. How participants acquired their PrU knowledge was not assessed in a structured way; however, participants were all patients seen in the rehabilitation clinic where care was provided by a team that includes wound care specialists. This may account for the fairly high self-reported baseline PrU knowledge and practice. This pilot study adapted a validated instrument to assess changes in knowledge and PrU prevention practices. This instrument did not assess all aspects of the content covered in the e-learning program (eg, caregiver issues). Although the participants accepted and were satisfied with the program, further testing in larger trials is required to measure effects on specific preventive behaviors (such as weight shifts, skin checks, and engagement in exercise programs and healthy nutrition) to test empirically whether adherence to these behaviors results in fewer PrUs. Also, additional testing is needed with individuals less knowledgeable about PrU prevention, as well as with individuals who are less comfortable using computers. Rigorous, well-designed RCT trials are necessary to test whether PrU prevention programs can successfully reduce PrU incidence in users over the long-term.18

In addition, this e-learning program is intended as a stand-alone, free choice learning program. The question remains whether, given access, users who need it would choose to use it on their own or whether it would be more effective as a structured intervention integrated into formal rehabilitation programs. Further evaluation involving large samples is necessary to confirm the program’s efficacy. In addition, the current study’s single-use design did not allow the author to assess the complete scope of program content. The program was designed to be used in multiple sessions, and it will be important to conduct further studies to learn what represents the optimal dose of prevention education. It also will be important to follow program users over a period of time to see if changes in knowledge and behavior are sustained.

Conclusion

An interactive e-learning program to educate adults with SCI about PrUs was developed and pilot-tested among 14 persons. A set of validated instruments was used to measure participants’ experiences and perceptions of the Internet program, and an instrument based on the NAC was used to measure knowledge and skin care management practices. The program was well received by the study participants. Prevention programs delivered over the Internet may be an increasingly important part of providing education that can be delivered as needed and when required to individuals who would otherwise not receive it. The program can be accessed at: www.healthlearnpa.com/Pressure-Ulcer-Program.php.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the nursing staff members for their participation in the study recruitment and data collection. In addition, the author thanks Michele Hilgart for her assistance with this study.

Dr. Schubart is Assistant Professor, Departments of Surgery, Medicine, and Public Health Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, Hershey, PA. Please address correspondence to: Jane Schubart, PhD, MS, MBA, Departments of Surgery, Medicine, and Public Health Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine, 500 University Drive, Hershey, PA 17033; email: jschubart@hmc.psu.edu.

1. Chen Y, Devivo MJ, Jackson AB. Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(6):1208–1213.

2. Krause JS, Broderick L. Patterns of recurrent pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: identification of risk and protective factors 5 or more years after onset. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(8):1257–1264.

3. Niezgoda JA, Mendez-Eastman S. The effective management of pressure ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006;19(suppl 1):3–15.

4. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J Spinal Cord Med. 2008;31(3):357–358.

5. Krouskop TA, Noble PC, Garber SL, Spencer WA. The effectiveness of preventive management in reducing the occurrence of pressure sores. J Rehabil R D. 1983;20(1):74–83.

6. Crenshaw RP, Vistnes LM. A decade of pressure sore research: 1977–1987. J Rehabil Res Dev. 1989;26(1):63–74.

7. Zulkowski K, Langemo D, Posthauer ME. Coming to consensus on deep tissue injury. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005;18(1):28–29.

8. Berry C, Kennedy P, Hindson LM. Internal consistency and responsiveness of the Skin Management Needs Assessment Checklist post-spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2004;27(1):63–71.

9. Smith BM, Guihan M, LaVela SL, Garber SL. Factors predicting pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injuries. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;87(9):750–757.

10. Dorsett P, Geraghty T. Health-related outcomes of people with spinal cord injury — a 10-year longitudinal study. Spinal Cord. 2008;46(5):386–391. 1

1. Krause JS, Carter RE, Pickelsimer EE, Wilson D. A prospective study of health and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(8):1482–1491.

12. Garber SL, Rintala DH, Holmes SA, Rodriguez GP, Friedman J. A structured educational model to improve pressure ulcer prevention knowledge in veterans with spinal cord dysfunction. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2002;39(5):575–588.

13. Rintala DH, Garber SL, Friedman JD, Holmes SA. Preventing recurrent pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury: impact of a structured education and follow-up intervention. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(8):1429–1441.

14. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines. Pressure ulcers: what you should know — a guide for people with spinal cord injury. 2002. Available at: www.pva.org/site/apps/ka/ec/product.asp?c=ajIRK9NJLcJ2E&b=6423003&en=feIEIIOnEaLDIIMsFfKDKIPsHjITKXPtH9KFIRMuGkLVI7K&ProductID=883955. Accessed February 20, 2012.

15. Caliri MH. Spinal cord injury and pressure ulcers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2005;40(2):337–347.

16. Jones ML, Mathewson CS, Adkins VK, Ayllon T. Use of behavioral contingencies to promote prevention of recurrent pressure ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84(6):796–802.

17. Moore Z. Improving pressure ulcer prevention through education. Nurs Stand. 2001;16(6):64–70.

18. Regan MA, Teasell RW, Wolfe DL, Keast D, Mortenson WB, Aubut JA. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(2):213–231.

19. Garber SL, Rintala DH, Hart KA, Fuhrer MJ. Pressure ulcer risk in spinal cord injury: predictors of ulcer status over 3 years. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(4):465–471.

20. Sheppard R, Kennedy P, Mackey CA. Theory of planned behaviour, skin care and pressure sores following spinal cord injury. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2006;13(4):358–366.

21. Thietje R, Giese R, Pouw M, Kaphengst C, Hosman A, Kienast B, et al. How does knowledge about spinal cord injury-related complications develop in subjects with spinal cord injury? A descriptive analysis in 214 patients. Spinal Cord. 2011;49(1):43–48.

22. Martin L, Haskard-Zolnierek K, DiMatteo MR. Health Behavior Change and Treatment Adherence: Evidence-based Guidelines for Improving Healthcare. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

23. Morrison G, Ross S, Kemp J. Designing Effective Instruction, 4th ed. Danvers, MA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc;2003.

24. Reigeluth CM. Instructional-Design Theories and Models: An Overview of Their Current Status. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers;1983.

25. Richey RC, Klein JD. Developmental research methods: creating knowledge from instructional design and development practice. J Comput Higher Ed. 2004;162:23–38.

26. Bloom BS, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. White Plains, NY: Longmans;1956.

27. Kirshner D, Whitson JA. Situated Cognition: Social, Semiotic and Psychological Perspectives. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers;1997.

28. Schank R. Inside Multi-media Case-based Instruction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers;1998.

29. Schank RC. Dynamic Memory Revisited. West Nyack, NY: Cambridge University Press;1999.

30. Schank RC. Designing World Class E-Learning, 1st ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2002.

31. Wiggins G. A true test: toward more authentic and equitable assessment. Phi Delta Kappan. 1989;70(9):703–713.

32. Bandura A. Social Learning Theory, 10th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc; 1977.

33. Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Coley B. Experimental component analysis of a behavioral HIV-AIDS prevention intervention for inner-city women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(4):687–693.

34. Prochaska JO, Redding CA, Harlow LL, Rossi JS, Velicer WF. The transtheoretical model of change and HIV prevention: a review. Health Educ Q. 1994;21(4):471–486.

35. Fisher WA, Fisher JD. Understanding and promoting AIDS preventive behaviour: a conceptual model and educational tools. Can J Hum Sex. 1992;1:99–106.

36. Kearsley G. Explorations in learning and instruction: the theory into practice database. 2003. Available at: www.stanford.edu/dept/SUSE/projects/ireport/articles/general/Educational%20Theories%20Summary.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2012.

37. Schubart JR, Hilgart M, Lyder C. Pressure ulcer prevention and management in spinal cord-injured adults: analysis of educational needs. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2008;21(7):322–329.

38. Brace JA, Schubart JR. A prospective evaluation of a pressure ulcer prevention and management e-learning program for adults with spinal cord injury. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2010;56(8):40–50.

39. Guihan M, Garber SL, Bombardier CH, Durazo-Arizu R, Goldstein B, Holmes SA. Lessons learned while conducting research on prevention of pressure ulcers in veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88(7):858–861.

40. Holmes SA, Rintala DH, Garber SL, Friedman JD. Prevention of recurrent pressure ulcers after myocutaneous flap. J Spinal Cord Med. 2002;25(suppl 1):S23.

41. Henzel MK, Bogie KM, Guihan M, Ho CH. Pressure ulcer management and research priorities for patients with spinal cord injury: consensus opinion from SCI QUERI Expert Panel on Pressure Ulcer Research Implementation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2011;48(3):xi–xxxii.

42. Kinzie MB. Instructional design strategies for health behavior change. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56(1):3–15.

43. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986.

44. Rosenstock I, Strecher V, Becker M. The health belief model and HIV risk behavior change. In: DiClemente R, Peterson J, Lagier R (eds). Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. New York, NY: Plenum Press;1994:5–24.

45. Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and exercise of control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente R, Peterson J, Lagier R (eds). Preventing AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1994:25–59.

46. Dearing J, Meyer G, Rogers EM. Diffusion theory and HIV risk behavior change. In: DiClemente R, Peterson J (eds). Precenting AIDS: Theories and Methods of Behavioral Interventions. New York, NY: Plenum Press;1994:79–92.

47. Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed. New York, NY: The Free Press;1995.

48. Ritterband LM, Thorndike FP, Cox DJ, Kovatchev BP, Gonder-Frederick LA. A behavior change model for internet interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2009;38(1):18–27.

49. Vaishampayan A, Clark F, Carlson M, Blanche EI. Preventing pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury: targeting risky life circumstances through community-based interventions. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011;24(6):275–284.

50. Ritterband LM, Ardalan K, Thorndike FP, Magee JC, Saylor DK, Cox DJ, et al. Real world use of an Internet intervention for pediatric encopresis. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10(2):e16.

51. Thorndike FP, Saylor DK, Bailey ET, Gonder-Frederick L, Morin CM, Ritterband LM. Development and perceived utility and impact of an Internet intervention for insomnia. E J Appl Psychol. 2008;4(2):32–42.

52. Berry C, Kennedy P. A psychometric analysis of the Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC). Spinal Cord. 2003;41(9):490–501.

53. Kennedy P, Evans MJ, Berry C, Mullin J. Comparative analysis of goal achievement during rehabilitation for older and younger adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(1):44–52.

54. Ritterband LM, Gonder-Frederick LA, Cox DJ, Clifton AD, West RW, Borowitz SM. Internet interventions: in review, in use, and into the future. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2003;34(5):527–534.

55. Matter B, Feinberg M, Schomer K, Harniss M, Brown P, Johnson K. Information needs of people with spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009;32(5):545–554.

56. Drainoni ML, Houlihan B, Williams S, Vedrani M, Esch D, Lee-Hood E, et al. Patterns of Internet use by persons with spinal cord injuries and relationship to health-related quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(11):1872–1879.

57. Burkell JA, Wolfe DL, Potter PJ, Jutai JW. Information needs and information sources of individuals living with spinal cord injury. Health Info Libr J. 2006;23(4):257–265.

58. Houlihan BV, Jette A, Paasche-Orlow M, Wierbicky J, Ducharme S, Zazula J, et al. A telerehabilitation intervention for persons with spinal cord dysfunction. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90(9):756–764.