Challenging Cases: Hydroconductive Dressing for Peristomal Skin Injury

Introduction

The decision to perform a tracheostomy on an infant or older child receiving chronic respiratory support is complex and difficult. Tracheostomy is indicated for a variety of reasons in the pediatric and neonatal populations. In the neonate, tracheostomy is a way to provide clinical stability, enhance survival, and optimize long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. In an older child, it may be a temporary measure in respiratory failure due to trauma sequelae or an illness, or a symbol of “futility” in a progressive disorder. Almost 5000 pediatric tracheostomies are performed annually in the United States.1

Skin breakdown and ulcerations are reported as early complications in the peristomal skin in 30% of patients.2 Maintenance of skin integrity can be challenging because increased secretions, perspiration, drooling, short neck, voluminous skin folds, and immobility contribute to increased moisture- and friction-related injuries. Pressure injuries from the flanges, ties, and stoma may exacerbate the severity of moisture-related breakdown.

Management usually includes regimented protocols, dedicated teams, daily skin assessment, and immediate placement of barrier materials. Foam dressings such as Mepilex Lite or Mepilex Ag (Mölnlycke, Gothenburg, Sweden), moisture-wicking fabric, gauze, hydrofiber, and skin protectants are often used as the initial preventive product as well as treatment if injury develops. Using pressure-reducing tubes that feature longer, flexible-extension separating flanges and reducing shearing forces on the surrounding skin can be attempted in children with short or full neck. Woven cotton, hook-and-loop, and foam ties have all been used. Neonatal practitioners prefer hook-and-loop ties due to faster change times, ease of placement, and slightly decreased rate of irritation.3 In the author’s institution, the most common foam used circumferentially around the neck and under the stoma/flanges is Mepilex Lite foam. Cavilon No Sting barrier (3M, Saint Paul, MN) is our choice for a non-stinging skin barrier for all patients. Despite the use of these 2 preventive products, we still find progressive irritant moisture dermatitis, leading to significant erythema, erosions, and weeping lesions in addition to peristomal granulation tissue formation.

In patients with tracheostomies, I have found that an increase in secretions is often associated with tracheitis, pneumonia, and worsening lung function due to pulmonary hypertension and agitation. Secretions due to an infectious etiology most likely have fluid composed of bacterial or viral debris, inflammatory cytokines, sloughed cells, and pro-inflammatory mediators. I look for a peristomal dressing that is slightly thicker, with strong wicking and absorptive properties eliminating the need for frequent changes, and one with an easy fit around the stoma and under the flanges, without significant lift and risk of dislodgement.

Drawtex Tracheostomy dressing (Urgo Medical, Fort Worth, TX) is a hydroconductive, nonadherent wound dressing with the ability to draw exudate, debris, bacteria, and proteases from the wound. Vertical and horizontal exudate dispersion controls and retains wound fluid so that it can be transferred to additional dressing layers if needed. LevaFiber technology (a combination of 2 types of absorbent materials with unique structures) provides 3 types of action: capillary, electrostatic, and hydroconductive. The small, porous material of the dressing allows the pores to act as capillaries, with intermolecular forces attracting exudate into the surface against the force of gravity. Electrostatic action refers to negatively charged bacterial attraction to the positively charged surface of the dressing. Finally, the hydroconductive action refers to the ability of fluid to flow through porous media, against gravity, both vertically and horizontally, and, if necessary, to transfer the exudate to a secondary dressing. Studies in adults have shown the effectiveness of this dressing in a few areas, including removal of devitalized tissue and exudate as well as a decrease in bacterial level and proteases.4-7 Wolvos5 demonstrated that hydroconductive dressings actively drew fluid away from the wound up to 150 mL/hr, retaining its integrity when moist. It selectively removed debris from the wound by drawing out adherent fibrin and slough, while leaving healthy granulation tissue in place.5 Ortiz et al7 demonstrated a decrease in bacterial counts on the wound surface and usefulness of the dressing in patients with burns. Multiple studies in adults have demonstrated a decrease in harmful matrix metalloproteases on the wound surface with dressing application, decreasing inflammation, edema, and subsequent erythema.8,9

Case Reports

Case 1 involved a 5-month-old, ex-25-week preterm baby with multiple abnormalities including congenital giant omphalocele, persistent pulmonary hypertension, and respiratory failure necessitating tracheostomy placement to stabilize frequent hypoxemia. Her overall complex course was complicated by abundant secretions, perfused sweating during agitation, and minimal movement due to omphalocele. Standard foam did not prevent dermatitis during exacerbations. Excessive neck movement, sweating, and secretions led to peristomal granulation (Figure 1A). The hydroconductive dressing decreased moisture and provided a soft, thick barrier (Figure 1B). Neck dermatitis improved, and granulation diminished. After a few episodes of dermatitis, the daily barrier was switched to the hydroconductive dressing permanently. The patient was eventually discharged home with this product. Her caretaker reported good results at home, specifically easy placement and good dressing longevity (3–4 days).

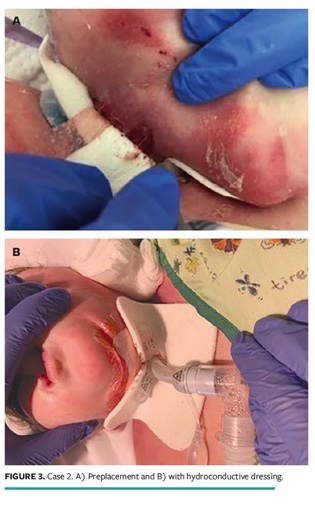

We have used this dressing on several of our complex patients with tracheostomy as both inpatient and outpatient management (Figure 2). If moisture-associated breakdown causes a significantly denuded wound, the dressing is combined with a cyanoacrylate liquid barrier application to maximize skin dryness and protect existing injury, as was done in case 2.

Case 2 involved significant neck dermatitis and erosions in a 2-year-old child who was developmentally delayed and was admitted with pneumonia (Figure 3). Standard silicon dressing and foam were inadequate in injury prevention and treatment. This led to changing the patient’s dressing to a hydroconductive one and to paint the affected areas with cyanoacrylate liquid (Marathon; Medline Industries, Northfield, IL). The patient’s condition improved within 3 to 4 days.

Conclusion

Drawtex dressing comes in a variety of shapes and sizes. The tracheostomy dressing has a precut keyhole aperture in the dressing. It fits neatly around the tracheostomy tube, wicking ongoing exudate from the tracheostomy site. I have managed severe peristomal breakdown around gastrostomy tubes with this dressing as well. The rope variety can be wrapped around any tube as a moisture-absorbent material to prevent moisture-associated dermatitis. Pediatric practitioners dealing with complex patients with various moisture and stoma-related injuries should consider the use of the hydroconductive dressing.

Affiliations

Dr. Boyar is director of Neonatal Wound Services, Cohen Children’s Medical Center of New York, New Hyde Park, and assistant professor of Pediatrics, Zucker School of Medicine, Hofstra/Northwell, Hempstead, NY. All photos provided are with the consent of the patients’ parents. This article was not subject to the Wound Management & Prevention peer-review process

References

1. Baket LR, Chorney SR. Reducing pediatric tracheostomy wound complications: an evidence-based literature review. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33(6):324–328. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000661808.51766.9a

2. Jaryszak EM, Shah RK, Amling J, Peña MT. Pediatric tracheostomy wound complications: incidence and significance. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(4):363–366. doi:10.1001/archoto.2011.33

3. Hart CK, Tawfik KO, Meinzen-Derr J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Velcro versus standard twill ties following pediatric tracheostomy. Laryngoscope. 2017;127(9);1996–2001. doi:10.1002/lary.26608

4. Spruce P. Preparing the wound to heal using a new hydroconductive dressing. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2012;58(7):2–3.

5. Wolvos T. Analysis of wound bed documentation in advanced wound care using Drawtex, a hydroconductive dressing with LevaFiber technology. Wounds. 2012;24(9)(suppl):S9–S10.

6. Wolcott RD, Cox S. The effects of a hydroconductive dressing on wound biofilm. Wounds. 2012;24(suppl):S14–S16.

7. Ortiz RT, Moffatt LT, Robson MC, Jordan MH, Shupp JW. In vivo and in vitro evaluation of the properties of Drawtex LevaFiber wound dressing in an infected burn wound model. Wounds. 2012;24(suppl):S3–S5.

8. Ochs D, Uberti G, Donate GA, Abercrombie M, Mannari R, Payne WG. Evaluation of mechanisms of action of a hydroconductive wound dressing (Drawtex) in chronic wounds. Wounds. 2012;24(suppl):S6–S8.

9. Wendelken M, Lichtenstein P, DeGroat K, Alvarez O. Detoxification of venous ulcers with a novel hydroconductive wound dressing that absorbs and transports chronic wound fluid away from the wound. Wounds. 2012;24(suppl):S11–S13.