Late Hematoma After Feminizing Augmentation Mammoplasty Mimicking Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL)

© 2024 HMP Global. All Rights Reserved.

Any views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and/or participants and do not necessarily reflect the views, policy, or position of ePlasty or HMP Global, their employees, and affiliates.

Abstract

We report the case of an Asian transgender patient with late hematoma after feminizing mammoplasty. Bilateral silicone breast implants were inserted into the patient 25 years previously. The right breast gradually became swollen without any specific cause, along with erythema and pain. Positron emission tomography showed right axillary lymphadenopathy. The mass and the axillary lymph node were surgically removed. Pathologic examination of the excised specimen revealed only hematoma formation and inflammatory granulation. At follow-up at 6 months postoperatively there was no reformation of hematoma. The presented symptoms are similar to those of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma, so there can be difficulty in differentiating between these 2 complications. We compared the clinical characteristics between our case of late hematoma and reported breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma after feminizing mammoplasty. Life-threatening breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma should be ruled out from late hematoma according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network screening guidelines.

Introduction

Hematomas can be a postoperative complication in patients undergoing reconstructive or aesthetic breast surgery with a silicone implant. Most hematomas after insertion of silicone breast implants (SBI) occur within 3 days after surgery, with a relatively high incidence of 2% to 10%.1-3 In contrast, late hematomas that occur more than 6 months after surgery are rare.4 Our patient had late hematoma after feminizing mammoplasty. The clinical presentation of late hematoma in our patient was very similar to that of life-threatening breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL), which is well known as a late complication after SBI insertion.5,6 Differential diagnosis between these 2 conditions was necessary. Here we present the first known report of a case of late hematoma after feminizing mammoplasty with comparison of the characteristics with the reported cases of BIA-ALCL after feminizing mammoplasty.

Case Report

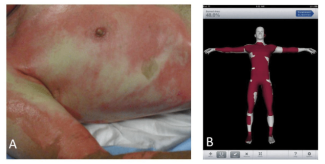

A 56-year-old Japanese transgender individual identifying as a woman had bilateral textured SBI inserted 25 years previously by a cosmetic surgeon for feminizing breast augmentation. She had undergone male to female sex reassignment surgery 12 years before the current presentation. She had taken hormonal drugs for about 5 years in her thirties. She took no oral medications such as anticoagulants or hormonal drugs after age 40. Two years prior to her visit to our department, her right breast became swollen without any specific cause. Redness and pain were observed 2 months prior to her visit. We observed redness, swelling, and abnormal morphology of the right breast (Figure 1). Blood tests showed no elevated inflammatory response or tumor marker or coagulation system abnormality (WBC 5,030/µl, CRP 0.11 mg/dL, PT-INR 0.9, APTT 30.6 seconds, IL-2 657). Computed tomography (CT) image showed a mass had formed under the ruptured SBI, and positron emission tomography (PET/CT) image showed swelling of the right axillary lymph node (Figures 2 and 3). Ultrasound-guided aspiration of fluid was performed and cytologically examined. However, flow cytometry showed no significant findings with few lymphocytes, and Giemsa banding could not be performed with little cell counts. Mammotome biopsy suggested a diagnosis of hematoma, but the possibility of breast implant–associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) could not be ruled out. The SBI ruptured just before surgery, so the mass and the axillary lymph node were surgically removed (Figure 4). Pathologic examination of the excised specimen revealed only hematoma formation and inflammatory granulation. At follow-up at 6 months postoperatively, there was no reformation of hematoma (Figure 5).

Figure 1. Clinical picture at presentation.

Figure 2. Computed tomography findings. Yellow arrow indicates the hematoma, red indicates the ruptured silicone breast implant.

Figure 3. PET-CT findings. Yellow arrow indicates swelling of the right axillary lymph node.

Figure 4. Clinical picture during surgery. The silicone breast implant ruptured just before surgery from ulcer. The hematoma was resected including the ulcered skin (yellow arrow).

Figure 5. Clinical picture 6 months after surgery.

Discussion

Complications in feminizing augmentation mammoplasty are generally rare, but a small number have been reported.7,8 Complications are typically divided into early (< 4 weeks) or late complications (> 4 weeks).7 Hematomas tend to present early (within 1-2 weeks) after augmentation mammoplasty, typically as a localized or unilateral swelling accompanied by pain and bruising at the surgical site.7 Late hematomas (> 6 months postoperatively), however, are much less common.

Various theories have been proposed regarding the etiology of late hematoma, which most likely result from erosion of capsular vessels due to trauma, inflammation, microfracture of the capsule, or friction between the implant and the capsule.2,4,9,10 Progression of late hematomas has been compared with that of chronic subdural hematomas, with small recurrent bleeds forming clots that create osmotic environments that slowly pull fluid into the capsule over time.5,11

Late hematomas usually present as unilateral swelling of a breast, sometimes accompanied with redness, pain, fluid retention, mass formation, and ulceration. It is more commonly chronic and progressive, but occasionally there is acute presentation.5,12-14 These symptoms are similar to BIA-ALCL after breast implant insertion, which is a life-threatening complication. BIA-ALCL is a type of T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a malignant tumor arising from the capsular tissue formed around breast implants that typically presents as sudden onset unilateral breast swelling 7 to 10 years after implantation.5,15 Other described symptoms have included spontaneous periprosthetic fluid collection or capsular mass, skin rash, capsular contracture, and lymphadenopathy. Most cases, like ours, have a clinical history of a textured implant.16

We compared the clinical characteristics between the present case of late hematoma and reported BIA-ALCL cases after feminizing mammoplasty (Table). There have been only 5 reported cases of BIA-ALCL after feminizing mammoplasty in transgender patients.17-22 The patient’s ages ranged between 27 and 56 years old (mean 45.2 years old). The interval from SBI insertion to initial symptoms ranged between 1 and 9 years (mean 4.6 years). The interval from initial symptoms to diagnosis was between 0.5 and 15 years (mean 6.3 years). All patients had textured type implants. Mass formation was observed in 4 of the 5 reported cases and they belonged to the late stage of BIA-ALCL. The initial and presented symptoms were quite similar between the present case and BIA-ALCL cases.

Breast augmentation using SBI has been widely performed in the field of cosmetic surgery. However, in cases of feminizing mammoplasty or cosmetic breast augmentation, there is typically no regular postoperative checkup. Most delayed complications are therefore assumed to be reported with a delay from the onset, and there may be many untreated cases of late complications. Differentiating between these complications from the initial and presenting symptoms only is likely to be difficult. PET-CT showed axillary lymph node accumulation in our patient, so it was especially difficult to differentiate from BIA-ALCL. When such symptoms are present, it is necessary to retain these 2 complications as important differential diagnosis. Furthermore, long-term follow-up and education of patients about the possibility of late complications are also necessary for early detection, including after cosmetic and feminizing mammoplasty. BIA-ALCL is a rare disease at most medical centers, so inclusion of a clinical history and directions to the pathologist to rule out BIA-ALCL is recommended. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network has recommended guidelines for BIA-ALCL diagnosis and management.6 Providers should adhere to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network BIA-ALCL screening guidelines for patients presenting with symptoms mimicking BIA-ALCL.

Conclusions

Late hematoma after feminizing mammoplasty can have similar symptoms to BIA-ALCL. Life-threatening BIA-ALCL should be ruled out from late hematoma adhering to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network BIA-ALCL screening guidelines.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge proofreading and editing by Benjamin Phillis at the Clinical Study Support Center, Wakayama Medical University.

Authors: Kazuki Ueno, MD, PhD1; Yasuhiro Sakata, MD1; Mari Kawaji, MD2; Miwako Miyasaka, MD2; Shinichi Asamura, MD, PhD1

Affiliations: 1Department of Plastic Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, 811-1 Kimiidera, Wakayama, Wakayama, 641-0012, Japan; 2Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Wakayama Medical University, 811-1 Kimiidera, Wakayama, Wakayama, 641-0012, Japan

Correspondence: Kazuki Ueno; kueno@wakayama-med.ac.jp

Ethics: Informed consent was provided for the use of images.

Disclosures: The authors disclose no relevant financial or nonfinancial interests.

References

1. Georgiade NG, Serafin D, Barwick W. Late development of hematoma around a breast implant, necessitating removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;64(5):708-710.

2. Hsiao H-T, Tung K-Y, Lin C-S. Late hematoma after aesthetic breast augmentation with saline-filled, textured silicone prosthesis. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2002;26:368-371.

3. Marcasciano M, Frattaroli J, Mori F, et al. The new trend of pre-pectoral breast reconstruction: an objective evaluation of the quality of online information for patients undergoing breast reconstruction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43:593-599.

4. Brickman M, Parsa NN, Parsa FD. Late hematoma after breast implantation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28:80-82.

5. Vorstenbosch J, Chu JJ, Ariyan CE, McCarthy CM, Disa JJ, Nelson JA. Clinical implications and management of non-BIA-ALCL breast implant capsular pathology. Plast Reconstr Surg. Jan 1 2023;151(1):20e-30e. doi:10.1097/prs.0000000000009780

6. Clemens MW, Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM. 2019 NCCN Consensus guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Aesthet Surg J. Jan 31 2019;39(Suppl_1):S3-S13. doi:10.1093/asj/sjy331

7. Wang ED, Kim EA. Perioperative and postoperative care for feminizing augmentation mammaplasty. University of California, San Francisco Transgender Care & Treatment Guidelines. Accessed October 1, 2023. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/chest-surgery-feminizing

8. Kanhai RC, Hage JJ, Asscheman H, Mulder WJ, Hage J. Augmentation mammaplasty in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(2):542-549.m

9. Görgü M, Aslan G, Tuncel A, Erdogan B. Late and long-standing capsular hematoma after aesthetic breast augmentation with a saline-filled silicone prosthesis: a case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg.1999;23(6):443-444.

10. Mauro S, Eugenio F, Roberto B. Late recurrent capsular hematoma after augmentation mammaplasty: case report. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2005;29:10-12.

11. Roman S, Perkins D. Progressive spontaneous unilateral enlargement of the breast twenty-two years after prosthetic breast augmentation. Br J Plast Surg. Jan 2005;58(1):88-91. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.002

12. McArdle B, Layt C. A case of late unilateral hematoma and subsequent late seroma of the breast after bilateral breast augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2009 July;33(4):669-670. doi:10.1007/s00266-009-9325-0

13. Peters W, Fornasier V. Late unilateral breast enlargement after insertion of silicone gel implants: a histopathological study. Can J Plast Surg. 2007;15(1):19-28.

14. Roman S, Perkins D. Progressive spontaneous unilateral enlargement of the breast twenty-two years after prosthetic breast augmentation. Br J Plast Surg. 2005;58(1):88-91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2004.04.002

15. Clemens MW, Nava MB, Rocco N, Miranda RN. Understanding rare adverse sequelae of breast implants: anaplastic large-cell lymphoma, late seromas, and double capsules. Gland Surg. Apr 2017;6(2):169-184. doi:10.21037/gs.2016.11.03

16. Brody GS, Deapen D, Taylor CR, et al. Anaplastic large cell lymphoma occurring in women with breast implants: analysis of 173 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. Mar 2015;135(3):695-705. doi:10.1097/prs.0000000000001033

17. Orofino N, Guidotti F, Cattaneo D, et al. Marked eosinophilia as initial presentation of breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. Nov 2016;57(11):2712-2715. doi:10.3109/10428194.2016.1160079

18. de Boer M, van der Sluis WB, de Boer JP, et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma in a transgender woman. Aesthet Surg J. Sep 1 2017;37(8):NP83-NP87. doi:10.1093/asj/sjx098

19. Patzelt M, Zarubova L, Klener P, et al. Anaplastic large-cell lymphoma associated with breast implants: a case report of a transgender female. Aesthetic Plast Surg. Apr 2018;42(2):451-455. doi:10.1007/s00266-017-1012-y

20. Ali N, Sindhu K, Bakst RL. A rare case of a transgender female with breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma treated with radiotherapy and a review of the literature. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. Jan-Dec 2019;7:2324709619842192. doi:10.1177/2324709619842192

21. Materazzo M, Vanni G, Rho M, Buonomo C, Morra E, Mori S. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) in a young transgender woman: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2022 Sept;98:107520. doi:10.1016/j.ijscr.2022.107520

22. Zaveri S, Yao A, Schmidt H. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma following gender reassignment surgery: a review of presentation, management, and outcomes in the transgender patient population. Eur J Breast Health. Jul 2020;16(3):162-166. doi:10.5152/ejbh.2020.5480