Treatment Options for MS Continue to Evolve

Orlando—Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune, chronic inflammatory neuro- degenerative disorder of the central nervous system (CNS). It is the most common cause of debilitation in young people affecting individuals between 20 and 40 years of age. While no cure exists for MS, the number of therapeutic options is increasing. During a session at the NAMCP forum, Gary M. Owens, MD, president, Gary Owens Associates, editorial advisory member, First Report Managed Care, discussed treatment options and presented information on the payer perspective.

MS Overview

Dr. Owens opened the forum with an overview of MS and its pathophysiology. Worldwide, the incidence of MS is approximately 0.1% and 400,000 people in the United States are living with MS. This highly variable and unpredictable disease is more common in women and the risk of MS among first-degree relatives is 1% to 3%. Four disease patterns have been identified in MS: (1) relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS); (2) primary-progressive MS; (3) secondary-progressive MS; and (4) progressive-relapsing MS.

MS is characterized by CNS inflammation, demyelination, axonal injury, and axonal loss. Lesions of the CNS white matter, with loss of myelin, neuronal axons, and myelin-producing oligodenrocytes, characterize MS physiopathology. The relapses are initiated through peripheral activation of leukocytes that enter the CNS through a breached blood–brain barrier [Perspect Medicin Chem. 2014;6:65-72].

The pathophysiology of MS “is getting complicated,” said Dr. Owens, referring to T-and B-cell roles in MS. The view on the pathogenesis of MS has broadened in recent years with the focus not only on T-lymphocytes as the key cell type to mediate inflammatory damage within the CNS lesions. Emerging evidence suggests that B-lymphocytes may play a comparably important role both as precursors of antibody-secreting plasma cells and as antigen-presenting cells for the activation of T-cells, according to a study he cited by Lehmann-Horn and colleagues [Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6(3):161-173].

Treatment Options

MS patients will require disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) to alleviate symptoms and manage exacerbations. Dr. Owens continued the forum discussing the evolving landscape of treatments available for MS. First-generation MS therapies include interferon beta (IFNß)-1a, IFNß- 1b, glatiramer acetate, and natalizumab.

IFNß, a purified, lyophilized protein product generated by recombinant DNA techniques, was the first class of medica- tions the FDA approved for MS. They are administered by self-injection and side effects include injection site necrosis and flu-like symptoms. A drawback of IFNß is that some patients develop neutralizing antibodies, which can reduce treatment effectiveness.

Glatiramer acetate is a polyformer of 4 amino acids that is an inducer of specific T-helper 2 type suppressor cells. It has 2 dosage forms that are administered subcutaneously: (1) 20 mg administered daily; or (2) 40 mg administered 3 times per week at least 48 hours apart. Dr. Owens said no laboratory monitoring is necessary. The most common side effects include injection site reactions, chest pain, flushing, dyspnea, and palpitations.

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal IgG4ĸ antibody that selectively binds to the alpha4-integrin component of adhesion molecules found on lymphocytes, monocytes, and eosinophils. It works by stopping circulating lymphocytes from entering the CNS. The recommended dose is 300 mg intravenous (IV) infusion over 1 hour every 4 weeks. Data from the AFFIRM (Natalizumab Safety and Efficacy in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis) study demonstrated a 68% reduction in relapses over a 2-year period compared with placebo. While natalizumab is well-tolerated, he noted that it carries an increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). The risk appears to increase after 2 years or more on the treatment, but can be assessed with JV virus testing. Natalizumab is also associated with risk of rebound disease activity when treatment is stopped.

Dr. Owens also reviewed DMTs recently FDA approved. In MS, inflammation and neurologic oxidative stress can create a cyclical process that may lead to progressive damage. Nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) pathway is involved in cellular response to oxidative stress. Dimethyl fumarate works by activating Nrf2. Approved by the FDA in 2013, the recommended starting dose is 120 mg twice a day orally. After 7 days, the dose should be increased to the maintenance dose of 240 mg twice a day orally. The safety and efficacy of dimethyl fumarate has been assessed in various studies including the 2-year, phase 3 CONFIRM (Oral Fumarate in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis) trial. CONFIRM randomized patients to 240 mg dimethyl fumarate twice daily, 240 mg dimethyl fumarate 3 times daily, or 20 mg glatiramer acetate. The annualized relapse rate (ARR) over 2 years was 44% with dimethyl fumarate twice a day, 51% with dimethyl fumarate 3 times a day, and 29% with glatiramer acetate. The most common adverse events in the dimethyl fumarate groups were flushing and gastrointestinal events.

Alemtuzumab, approved by the FDA in 2014, is the newest MS treatment for patients with relapsing forms of MS. Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets CD52, a protein abundant on T-cells and B-cells. Circulating T-and B-cells are thought to be responsible for the damaging inflammatory process in MS. Alemtuzumab depletes circulating T- and B-lymphocytes after each treatment course. The recommended dosage is 12 mg/day administered by IV infusion for 2 treatment courses. The first treatment course is 12 mg/day on 5 consecutive days (60 mg total dose), and the second treatment course is 12 mg/day on 3 consecutive days (36 mg total dose) 12 months after first treatment course. He noted that alemtuzumab carries a Boxed Warning existing around hematologic toxicity, infusion reactions, and opportunistic infection.

Data from the phase 3 CARE-MS (Comparison of Alemtuzumab and Re- bif Efficacy in Multiple Sclerosis) studies comparing treatment with alemtuzumab to high-dose subcutaneous IFNß-1a in patients with RRMS who were either new to treatment (CARE-MS I) or who had relapsed on prior therapy (CARE- MS II) found that alemtuzumab was significantly more effective at reducing ARRs. The most common adverse reac- tions included nasopharyngitis, nausea, and urinary tract infection.

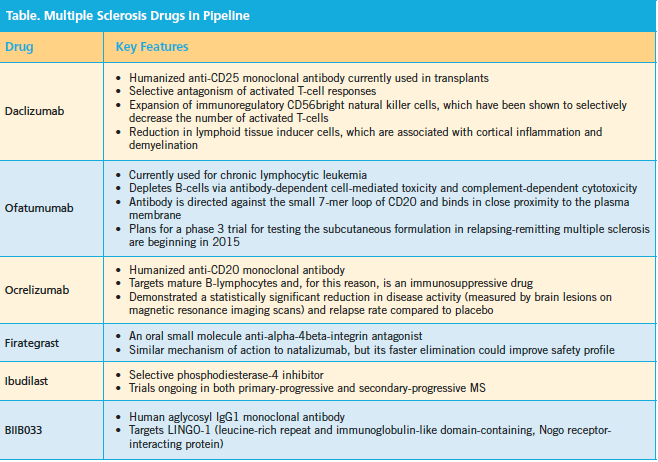

Dr. Owens also discussed MS therapies in the pipeline and their key features (Table).

Payer Approaches to MS Therapy

He wrapped up the forum discussing the payer perspective. There is currently insufficient Class 1 evidence for a detailed MS treatment algorithm. The lack of de- finitive clinical evidence to guide MS treatment decisions has become increasingly important as the number of therapeutics continues to increase annually.

Factors that will influence value in MS in the future include comparative effectiveness research, cost-effectiveness, payer influence, adaptive trial design, governmental policy influence, and de- velopment of MS guidelines on treatment algorithm. He cited a 2010 managed care network survey that ranked the importance of various types of information on formulary evaluation. The most important information was comparative effectiveness followed by clinical trials, budget impact, and cost-effectiveness.

Payers struggle with which drug is right for which patient. Payers must balance cost, outcomes, and access in decision- making for MS formularies, Dr. Owens said.—Eileen Koutnik-Fotopoulos