Review of FDA Drug Approvals between 2005 and 2012

Since enrolling at the Yale School of Medicine in 2010, Nicholas Downing has developed an interest in the FDA and its approval process for new drugs. Mr. Downing, 28, is now a fourth year medical student and considered a leading authority on an agency that decides the medications patients receive and the successes and failures of pharmaceutical companies that spend billions of dollars each year researching therapies.

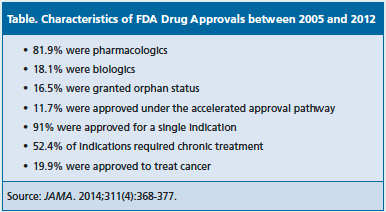

Mr. Downing was the lead author of a recent study that examined the pivotal efficacy trials leading to 188 FDA drug approvals for 208 indications between 2005 and 2012 [JAMA. 2014;311(4):368-377]. The authors found the quality and quantity of the studies varied, although most were randomized (89.3%), double-blinded (79.5%), and used an active or placebo comparator (87.1%).

However, Mr. Downing noted the FDA was flexible when it came to considering drugs intended to treat life-threatening and orphan diseases and the number of trials it required before approval. For instance, 36.8% of the indications were approved based on a single pivotal trial.

Manufacturers have a few options when trying to get drugs to market as soon as they can. The FDA’s fast track, accelerated approval, and priority review programs are intended for drugs treating serious conditions and filling unmet medical needs. In July 2012, the agency also introduced a breakthrough therapy designation for drugs that demonstrate significant improvement over existing therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

Of the drugs approved between 2005 and 2012, 11.7% were approved via the accelerated approval process and 16.5% were granted orphan status, signifying they were for diseases affecting <200,000 people in the United States. The trend toward approving orphan drugs and expediting review times has increased in recent years. Of the 27 drugs approved in 2013, 9 were identified as orphan products, 10 were designated as fast track, 10 were designated as priority review, 3 were designated as breakthrough, and 2 were approved under the accelerated approval process.

Despite the options available, pharmaceutical companies sometimes are concerned with the lack of guidance from the FDA. Mr. Downing said this analysis could aid them in better understanding the agency.

“We painted a picture of what it takes to get 188 novel drugs approved over the past 8 years and clearly outlined the clinical trial evidence that was necessary in order to win those approvals,” Mr. Downing said in an interview with First Report Managed Care. “That provides good insight into perhaps what the expectation of the agency is prior to awarding those approvals. I would hope this information might help remove some of that uncertainty about what it takes to win approval.”

Between January 2012 and June 2013, Mr. Downing and his coauthors gathered information from the FDA’s publicly accessible database on the agency’s Web site. They read the FDA’s medical review documents that are prepared for each novel therapy and included clinical evidence such as safety, efficacy, manufacturing, and chemistry. They evaluated drugs first approved between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2012, and excluded generic medications, reformulated drugs, and combination therapies.

“We did not specifically attempt to determine causality in our study,” said Mr. Downing, who plans on entering an internal medicine residency program in the fall. “We just tried to provide a systematic overview of what the drug approval process and the level of evidence presented in it looks like.”

Still, they had some noteworthy findings from the analysis, including that 52.4% of the indications required chronic treatment and 3 areas accounted for nearly half of approvals: 19.9% were for cancer, 14.1% were for infectious diseases, and 11.2% were for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, or hyperlipidemia. See Table for more on characteristics of drug approvals. Of the primary end points used in the pivotal trials, 48.9% were a surrogate outcome, 29% were a clinical outcome, and 22.1% were a clinical scale.

In the coming years, Mr. Downing said he may further study the 36.8% of indications approved after a single pivotal trial and the nearly 50% of drugs approved based on a surrogate end point.

“A very logical extension is to determine whether drugs that were approved on the basis of preliminary evidence continue to do well studied in the postmarket period and if additional confirmatory evidence, which could guide clinical decision making, is being generated systematically,” he said. “That is certainly an area of interest.”

Mr. Downing’s previous research included a comparison of the regulatory review time of medications by the FDA, Health Canada, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) between 2001 and 2010 [N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2284-93]. At the time, Congress was in negotiations to reauthorize the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA), which was first enacted in 1992 to accelerate drug approvals. Under PDUFA, pharmaceutical manufacturers pay a fee to the FDA to help expedite reviews.

The authors accessed publicly available databases and identified 510 applications for drugs approved by at least 1 of the agencies between 2001 and 2010. The median review time was 322 days for the FDA, 366 days for the EMA, and 393 days for Health Canada. Of the 72 drugs approved by all 3 agencies, the median review time was 268 days for the FDA, 356 days for the EMA, and 366 days for Health Canada.

They also found that among drugs approved in the United States and Europe, 63.7% were first approved in the United States and were available a median of 96 days earlier in the United States. Of the drugs approved in the United States and Canada, 85.7% were first approved in the United States and were available a median of 355 days earlier in the United States.

“The reason we did the international comparison is the correct speed of drug regulation and the regulatory review process is really unknowable,” Mr. Downing said. “Who is to say 10 months is the right amount of time? Maybe it is 12 months. Maybe it is 14 months. Maybe it is 6 months. What we felt was most useful was to do an international comparison with other regulators. You face the same type of pressures as the FDA—namely, to rapidly approve new drugs so that patients have access to new technologies as soon as possible without unduly delaying a promising technology from reaching the bedside.”