Meeting the Patient Where They Are: Home-Based Primary Care

As the push to deliver increasingly higher quality care at lower costs continues to be of the utmost importance, stakeholders and providers are implementing and testing a number of models to see what suits their patient population best. Home-based primary care is a top-perfomer among those models—although not necessarily a new concept—that is gaining popularity.

“Meeting people where they are” is commonly used to mean recognizing and providing people with what they need in values, emotions, and overall connecting in ways that are meaningful to the person. It also can mean to meet them literally where they are, in their home.

This is the basis of a growing movement to deliver primary care to the homes of people, for whom, the home is “where they are”. It is estimated that over 2 million older adults are homebound, making it difficult for them to access critical care, and this number is expected to double over the next 20 years. These are among the frailest patients with multiple chronic conditions and functional deficits that incur the highest health care costs. Data shows that the costliest 1% of the highest cost patients (ie, those with five or more chronic conditions and multiple functional deficits) incur 23% of the total costs of health care spending and the top 5% incur 50% of total costs.

Providing higher quality of care at reduced cost to this population is on the radar of most health care policymakers, with a variety of health care models and delivery systems being tested and adopted to fulfill this goal.

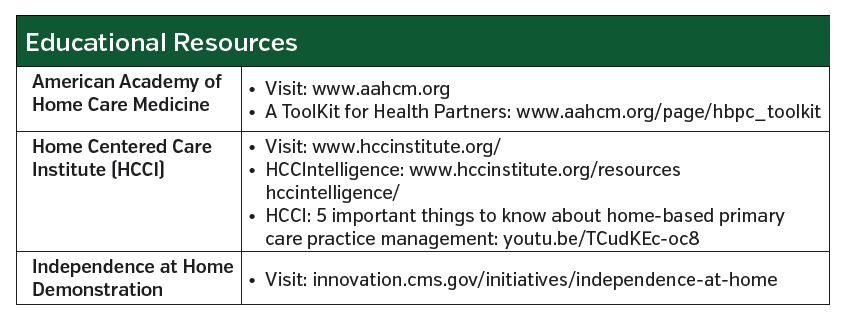

One approach that is far from new but growing in awareness and implementation is home-based primary care (HBPC). Although a number of academic health centers as well as large and small nonprofit groups have been involved in HBPC for many years, awareness of HBPC and its success in improving outcomes and reducing costs for the highest cost patients still lags.

“It’s [HBPC] just not widely disseminated,” said Katherine A Ornstein, PhD, associate professor, department of geriatrics and palliative medicine and associate professor, Institute for Translational Epidemiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NY, who is the research director for Mount Sinai at Home which includes the Mount Sinai Visiting Doctors, one of the largest academic HBPC program in the United States. “What we are finding is that about 10% of the homebound patients that we know exist are able to access home-based care.”

“That is pretty dismal,” Dr Ornstein said. “There are far more providers making nursing home visits than home-based primary care visits even though the current homebound population is larger than the nursing home population.”

But this is could be changing, suggests Thomas Cornwell, MD, a physician who has practiced HBPC since 1997 through Northwestern Medicine’s HomeCare Physicians and founded the nonprofit Home Centered Care Institute to raise public awareness through education and advocacy of HBPC.

In a white paper he first published in 2014 and updated in 2019, Dr Cornwell laid out a confluence of elements called a perfect storm that are fanning the sails of the modern house call movement. Along with an aging society, the fiscal Medicare and Medicaid crisis, and federal legislation, other elements include the strong evidence on the efficacy of HBPC to improve outcomes and reduce costs, lower hospital mortality through quality end-of-life care, and health care reform and alternative payment models.

Improving Outcomes and Reducing Cost

“The needs are growing for our older population and increasingly they want to stay at home, so we have to develop innovative care models to support them,” said Dr Ornstein. “Home-based primary care provides critical multidisciplinary care in the home and evidence suggest that it can improve quality of care and quality of life for patients.”

Evidence shows it also reduces cost. Among the most recent evidence of improved outcomes and reduced cost with HBPC are two studies published in 2014, one from the HBPC program at the Veterans Administration (VA) and the other from Medstar Washington Hospital Center Medical House Call Program.

Based on 2007 data, the VA HBPC program was associated with a 59% reduction in hospital stays, 89% reduction in nursing home days, and a 21% reduction in 30-day readmissions, as well as a 13.4% reduction in costs, 16.7% savings, and 10.8% savings to Medicare.

Findings from the Medstar Washington Hospital Center Medical House Call Program also showed savings with its HBPC program, with 17% reduction in Medicare representing a 2-year savings of $8477 savings per beneficiary and $6.1 million overall savings. For both programs, a reduction in hospitalization (and emergency department visits for the Medstar program) accounted for the major cost savings.

Other more recent evidence comes from a demonstration project through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Center that is showing consistent and continual savings with the use of HBPC. Initiated in 2012, and expanded through December 2020, the Independence at Home demonstration project tests whether HBPC can improve patient and caregiver satisfaction, improve health outcomes for beneficiaries, reduce the need for hospitalizations, and lower Medicare costs.

It currently includes 14 participating practices (of which one is a consortium of three practices). Beneficiaries eligible for inclusion in the project include those who have two or more chronic conditions, are covered by fee-for-service Medicare, require help with two or more functional dependencies, have had a nonelective hospital admission within the last year, and have received acute or subacute rehabilitation services within the last year.

Data from the most recent update at 5 years shows that cost reductions associated with the program. At 5 years, the expenditures for practices involved in the program were about 8.4% below their spending targets—equal to $33.5 million for 12,400 beneficiaries. This represents an average reduction of $2711 per beneficiary.

Bruce Kinosian, MD, professor in the division of geriatrics at The University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine—also with the Penn Medicine’s Truman G. Schnabel Geriatric Home-Based Primary Care Program, one of the 14 practices in the demonstration project—noted that during the initial 5 years of the Independence at Home project, the demonstration retained 82% of its practices, provided 54,331 patient-years of care to some of Medicare’s frailest and costliest beneficiaries, while generating over $100 million in savings.

“The Independence at Home program has been CMS’ most successful primary care program,” he said. “It has generated 11 times the savings without two-sided risk compared to risk-sharing accountable care organizations, while caring for the frailest and costliest Medicare beneficiaries.”

Providing specific 5-year outcomes from Penn Medicine’s In-Home Primary Program (ie, which is part of the consortium along with Mid-Atlantic collaborative and the Philadelphia Corporation of Aging), Dr Kinosian said that the cost reductions reflect the reduction in hospital readmissions, hospitalizations, ambulatory care hospitalizations, emergency department visits, as well as allowing patients to stay longer in community residences.

A critical component of the demonstration project is its reimbursement structure. It uses a shared savings mechanism within the fee-for-service traditional reimbursement model for Medicare. “Savings come from aligning incentives for patients and providers by having shared savings which imposes a budget constraint,” said Dr Kinosian. Practices who meet performance thresholds for at least three of six quality measures qualify for an incentive payment. In year 5, eight practices met the requirements for incentive payment and 13 of the 14 practices overall met or bettered their cost benchmark.

Reimbursement and Other Challenges

Finding a payment model that can adequately reimburse practices and providers is essential to making HBPC work. Moving to value-based payment models is favorable for HBPC because of the unsustainability of fee-for-service for the extremely challenging homebound population, according to Dr Ornstein. “Different kinds of value-based contracting are critical,” she explained, emphasizing the need to create an HBPC model that is cost-effective.

Brianna Plencner, CPC, CPMA, manager, practice improvement, Home Centered Care Institute (HCCI), Schaumberg, IL, also underscored the importance of moving toward reimbursing value over volume.

“The most successful model for this is a value-based contracting model where the home-based provider or practice is paid on their clinical outcomes, and either receives shared savings or has a per-month fee from the plan they contract with,” said Ms Plencner.

If practices and provider opt to use a fee-for-service model, she emphasized the need to take advantage of ways to maximize reimbursement. For example, she cited chronic care management or advanced care discussions as examples of advanced coding opportunities. Although not unique to HBPC, these reimbursable activities are important for HBPC providers given the greater amount of time spent on care coordination, managing psychosocial issues, and communication with patients and their caregivers.

Ms Plencner, who is an expert in billing and coding and recently spoke on these issues at the annual American Academy of Home Care Medicine, highlighted the need for practices to know what new codes to use and to be aware of different payment models. For example, she cited a new model that CMS will roll out in 2021 for implementation in 26 regions called Primary Care First Model that will offer a way to support delivery of advanced primary care.

Other challenges to implementing HBPC are issues related to scheduling, staffing, and recruiting. “From a practice management perspective, it is really important to have a geographical scheduling process,” said Ms Plencner, adding that minimizing travel times between home visits is important because home visits typically are longer than office visits.

Hiring the right team is critical. “From the provider, to your front office, to your back office, you really need staff that is engaged,” Ms Plencner said. “Providers who go into the home in particular need to be comfortable with different and sometimes difficult family dynamics.”

For those who are a good fit, she emphasized the many rewards. “Physicians appreciate the opportunity to practice medicine in a way that led them to go to medical school in the first place,” she said, adding that patient and provider satisfaction is generally in the 90th percentile in the home-based model. “That is far higher than the clinic setting,” she added.

Underlying the high satisfaction of provider and patient is the chance to develop a relationship, something that is more difficult in the clinic setting. “Most of us who do this think the secret sauce is the trust that is built up between patients and providers from the close relationship developed providing care in the patients’ home,” said Dr Kinosian.