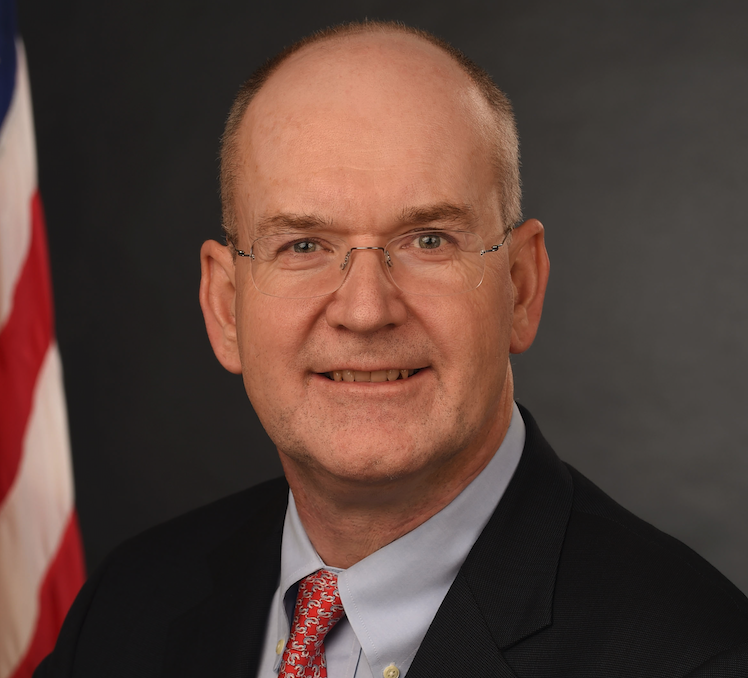

Managed Care Innovator: Donald Rucker

Managed Care Innovator: Donald Rucker

Health IT: Role of Government in the Digital Revolution

Considered a preeminent clinical informatics expert, Donald Rucker, MD, national coordinator for health information technology at the US Department of Health and Human services (HHS), has researched interface design for clinical applications and continues to study how to integrate systems and databases. Board-certified in emergency medicine, internal medicine, and clinical informatics, Dr Rucker has held several clinical and academic positions at Kaiser Permanente and The Ohio State University. He also holds the distinction of co-developing the world’s first Microsoft Windows-based electronic health record.

Considered a preeminent clinical informatics expert, Donald Rucker, MD, national coordinator for health information technology at the US Department of Health and Human services (HHS), has researched interface design for clinical applications and continues to study how to integrate systems and databases. Board-certified in emergency medicine, internal medicine, and clinical informatics, Dr Rucker has held several clinical and academic positions at Kaiser Permanente and The Ohio State University. He also holds the distinction of co-developing the world’s first Microsoft Windows-based electronic health record.

Dr Rucker recently sat down with First Report Managed Care to speak about the Office of the National Coordinator’s (ONC) role in the US health care system. We focused on the progress made with challenges related to interoperability, reducing provider burden, and giving patients control of their health data. Dr Rucker addressed online privacy concerns and talked about how managed care stakeholders can best position themselves for success.

What’s the best way to describe ONC’s role in US health care?

The best description is in our organization’s title—we coordinate HIT initiatives. We use modern computing and technology and standards to help facilitate a path to a solution. Plus, we offer new ways of looking at how to address problems.

You recently returned from the Health Information and Management Systems Society Health IT conference (HIMSS). How did it go there?

I would say things went very well. People have been waiting for the ONC and CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) interoperability rules and HIMSS is a natural audience for that. On a substantive note, people really intuit that interoperability is central to fixing a lot of American health care. This is evolving over time, but I think anybody who looks at it is thinking interoperability is at the core of potential solutions to many of our problems.

Can you give an example?

How do accountable care organizations (ACOs) become effective? It starts with the basics, If ACOs don’t know where the patient is being admitted and can’t find out when they’re discharged, they are not going to be very impactful. Interoperability becomes important.

Given that importance, can you talk about the accomplishments of your department since you took the position?

I’ve been here just a bit under 2 years. We’ve put a very detailed, substantive proposed rule out. The guidance on trusted exchange frameworks is probably the single biggest ask on our to-do list. Additionally, we work closely with the Health IT Advisory Committee. We’ve been heavily involved in supporting and encouraging the so-called FHIR standard—Fast Health care Interoperability Resources. We work with payers to extend these standards to population level data and are working on other interoperability standards. We are also involved with the CMS Promoting Interoperability Program [formerly the Medicare and Medicaid EHR Incentives Programs]. This certification program is really the technical underpinning for CMS.

What about efforts to reduce provider burden?

Ultimately, much provider burden is not due to the [electronic health record (EHR)], itself. Rather, it is a direct result of a series of problematic workflows—the documentation for billing workflow, the prior authorization workflow, and the quality measure documentation workflow. We are charged under the 21st Century Cures Act to work with CMS to help solve this burden. We recently released a report [the Strategy on Reducing Regulatory and Administrative Burden Relating to the Use of Health IT and EHRs] for public comment that identifies these issues and helps work through them. We worked with CMS to start reforming the evaluation and management billing code documentation that’s at the heart of a lot of inefficiency and provider burden. We are simplifying that and removing the perverse incentives there.

And how are things going in that regard?

It’s a work in progress. We’re working to build out the application programming interfaces (APIs) that one day might start replacing quality measures. For instance, instead of the provider extensively reporting quality measures to CMS or private payers, the clinician, under the secure application standards based-APIs that we have in our rule, would allow payers to use their HIPAA transactions, payment, and operations access rights to download the data they need. This can be done efficiently and at a much lower cost. It takes burden off the doctors and frankly, the American public, who ultimately pay for it.

What are the next steps from a technical standpoint to ensure optimal interoperability and access across platforms?

To me there are three major steps. Two of them are already incorporated in our proposed rule [to implement certain provisions of the Cures Act] that is out for public comment until May 3, 2019. The first is having an interface

for interoperability based on modern computing standards, the so-called RESTful interfaces and XML/JSON. We will move toward technical consistency and implementation predictability.

The second area involves information blocking, which is already prohibited by law. We are charged with writing the allowable exceptions, so they don’t become a barrier to the existence of outside apps and our rule proposes those exceptions. Our efforts go hand in hand with the CMS initiative to get Medicare claims data to beneficiaries, using the same class of standards.

The third area is something that Congress has asked us to do: Get various health information networks to more effectively communicate with each other. This is the digital on-ramp, if

you will. It falls under the Trusted Exchange Framework and Common Agreement, the first draft of which was released in 2018. It is a guidance framework document. We will issue a contract for an organization to get the

health information exchanges to formulate a common agreement and ultimately talk with each other.

Let’s turn to ONC’s Health IT Certification Program. What kind of progress is being made?

In recent years, the program has dealt with some pretty basic functionality; Can you generate a med list? Can you generate a problem list? Can you generate an allergy list? —information about chronic prescribing, which is mandated under law. Most of the baselines are in place. Now, we are focusing the certification programs on interoperability and making sure that application programming interfaces work.

In 2015, the program called for “the open application programming interface.” We are now moving toward standards-based application programming interfaces so app developers program just one API, as opposed to having each vendor [create] random nonstandard APIs.

HHS and your office are placing major emphasis on giving patients more control of their health information. What significant advances are being made in this area?

The American public does not have the benefit of an app economy in health care the way they do elsewhere. We have Uber and Lyft, Airbnb, banking, sports, weather, travel apps; and more. We don’t have that in health care because these things have essentially been locked down. Through innovation projects, we are opening up barriers that were created unintentionally by decades of government policies. I see

what we’re doing here as potentially the most disruptive and patient empowering. We want

to get patients back in control of their health care. ONC is a small, but important, part of it. More broadly, the [Trump] administration is focused on price transparency. We believe that allowing Americans to partake in an app economy will lead to better choices, more competition, lower prices, patient empowerment, and better care.

In some ways, it’s advantageous that health care has been lagging in this area. This has allowed other industries to innovate first. Do you agree?

Yes, the API technology is already built out in almost every other industry. We want to bring it to health care. I know some EMR [electronic medical records] vendors have voiced concern about security. On some level that’s nonsense. It’s secure in every other industry.

And just like in other industries, patients need to proceed cautiously and with eyes wide open.

Yes, they will have to make choices about which apps they use to get their data. They’ll have to decide what they want to do in terms of buying apps or using free apps that monetize their data a- la-Google and Facebook. That is a choice for the American citizen to make, not for the EMR vendor or provider.

Concern about online privacy is front and center. Buyer beware certainly makes sense. Well-informed people know how to control privacy online, but there are others who either don’t know or don’t take the time to know. What, if anything, is being done about that as the health care app economy expands?

Once the rule is final and the APIs are all installed as per the rule, the providers and the EMR vendors certainly are well within their purview to warn patients. Patients still have to log on initially to the provider portal to authenticate and get the data into their app. There will be nothing that prevents the EMR vendor from providing warning language—”Do you realize you’re putting this on an app? Is this app secure?” Plus, users have to log on using industry-standard protocol for authorization—OAuth 2.0. I think consumers will be able to control this in a way they haven’t before. Beyond that, I think the idea of [consumer protection] is a part of a broader or policy issue. What are our expectations and notifications about privacy in the app world? Congress may need to help sort this out. I know they’ve been asked by stakeholders to get involved. How far Congress takes it, is up to Congress.

The way I see it, there will be many consumer products, including health care apps. For each app, people will have to decide if it is a brand they trust. Apple has a very good record on privacy, certainly. Facebook’s record on privacy, or lack thereof, is public knowledge. I can imagine any of the consumer health brands getting into the fray. The way we deal with quality in America in unregulated markets is through brand recognition, star rating systems, and word of mouth. I see no reason why that can’t work in health care.

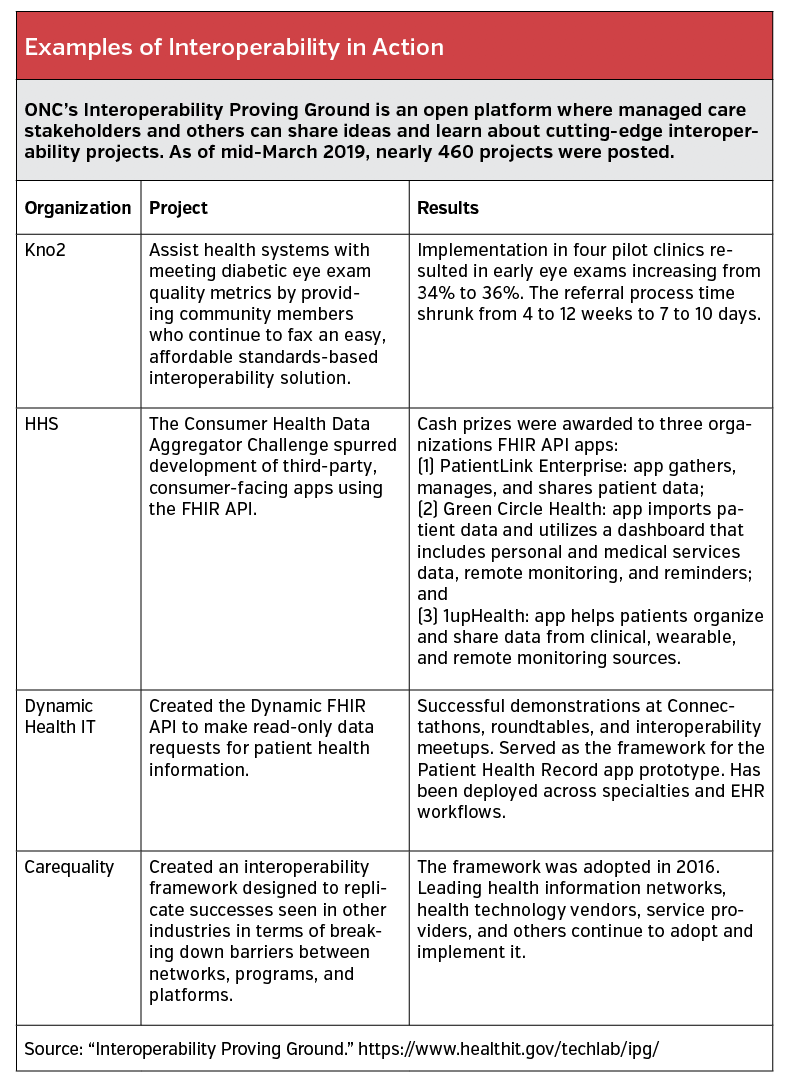

(article continues below table)

What do you see as the most important practical accomplishment that will result from more consumers accessing their health information?

What do you see as the most important practical accomplishment that will result from more consumers accessing their health information?

As consumers gain control of their health data, shop more smartly for care, and engage better in their care, you will see improved outcomes and cost savings. Give consumers control, rather than having third parties act on their behalf. There is no one more interested in a good patient outcome than the patient.

I know it’s challenging to provide an exact timetable, but when do you expect things to come to fruition?

As mentioned, our Cures Act rule proposal is open for comments until May 3, 2019. Once the final rule is released, perhaps at the end of 2019, the providers and the EMR vendors will have 24 months to put these endpoints out for the public. Now keep in mind that some of this data is already being released earlier. For instance, roughly 90% of EMR vendors already have FHIR endpoints available. Apple is headed there. There are a number of small companies who are building these endpoints. When you put this stuff back in market economy, people rush to get the apps out.

As HHS and ONC step on the gas pedal, if you will, what can managed care stakeholders do to position themselves for success?

They should think about the impact of an API-mediated world. New business models, historically, are often about new modes of communication. Whether that was the Pony Express, the transcontinental railroad, the telegraph, the phone line, radio, television, the internet, or the smartphone. In a practical sense, think about a health care economy where resources are provided in all kinds of different places beyond the doctor’s office and the hospital. What does that new connected universe mean?

Is telehealth a good example?

Sure, but it’s more than just that. Think about every component of care, whether it’s preventive medicine, acute medicine, referrals, providing prescriptions, managing chronic illness, tracking, social outreach, social determinants of health, in-home services—revisit every one of those things from an API-enabled world, as opposed to a world with a call center.