Exploring Drug Interactions in Older Adult Patients

Orlando—Drug interactions in older adults is a significant topic of concern for those managing medications in this vulnerable patient population. Increased awareness and interventions through a pharmacist–physician collaboration may help reduce exposure and minimize the risks associated with potentially harmful drug combinations in older adults, according to presenters who spoke on this topic during a session at the ASCP meeting. The presenters included Manju T. Beier, PharmD, CGP, FASCP, senior partner, Geriatric Consultant Resources, LLC, and Naushira Pandya, MD, CMD, FACP, professor and chair, department of geriatrics, Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Dr. Beier opened the session by outlining the scope of adverse events from drug interactions in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). She highlighted data from the 2014 Office of the Inspector General report that examined the incidence among Medicare beneficiaries. The report found that 22% of Medicare beneficiaries experienced adverse events during their SNF stay. An additional 11% experienced temporary harm events. Furthermore, 59% of these adverse events and temporary harm events were clearly or likely preventable. Overall, 66% of medication events were preventable.

Risk factors for drug interactions in this patient population include:

• Polypharmacy

• Critically ill, older, complex patients

• Patients on psychiatric and/or pain medications

• Genetic predisposition

• During transitions of care

Dr. Beier said potential outcomes of drug interactions can result in overt toxicity, reduced or lack of effect, prescribing cascade, and worsening of existing adverse events.

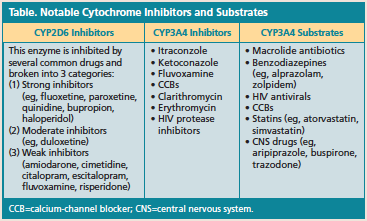

There are a number of mechanisms by which drugs interact, such as pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions occur when 1 drug affects the absorption (eg, changes in motility), distribution (eg, altered protein binding), metabolism (eg, CYP450 interactions in the liver), or excretion of another drug (eg, emphasis on renally excreted medicines and competitive elimination). Clinicians also have to consider factors that determine the time course for drug interactions caused by enzyme inhibitors, which can increase the risk of toxicity. Dr. Beier reviewed key

cytochrome inhibitors and substrates (Table).

Pharmacodynamic drug interactions occur when 2 drugs have additive or antagonistic pharmacologic effects. Additive pharmacodynamic effects include combination of drugs that increase bleeding risk, hyperkalemia, central nervous system depression, QT prolongation, serotenergic toxicity, renal toxicity, and liver toxicity. Examples include anticoagulants/antiplatelets and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drug combinations that can have antagonistic actions include NSAIDs and antihypertensive medications and haloperidol and levodopa/carbidopa, according to Dr. Beier.

The consultant pharmacist and physician/medical director partnership is critical to promote improved care quality in nursing homes and to help tackle drug interactions in this patient population. Both physicians and consultant pharmacists should try to prevent, anticipate, identify, and address adverse consequences related to medications. Face-to-face discussion is also beneficial, said Dr. Pandya. Another strategy is collaboration to reconcile cost and clinical considerations in relation to medication utilization.

Because effective communication is key in any clinical setting, Dr. Pandya recommended communication strategies to target some issues in nursing homes:

• Reduction of sliding scale insulin use

• Reduction on antipsychotics and optimization of dementia care

• Role of hypnotics

• Appropriate laboratory monitoring for chronic conditions

• Review of unplanned hospital admissions

• Accurate diagnoses documented for each medication

• Anticipation of drug–drug interactions—Eileen Koutnik-Fotopoulos