Ensuring Access to Primary Care for Medicare Beneficiaries

Between 2010 and 2017, the number of primary care physicians treating Medicare beneficiaries grew by 13%. During this same time, the ratio of primary care providers to beneficiaries dropped slightly from 3.8 per 1000 to 3.5 per 1000. It is this drop, described as “modest” in the June report by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) to Congress that foreshadows a concern for Medicare and private insurers alike—the decreasing number of primary care providers in a health care delivery system that relies on these frontline workers to deliver accessible, affordable, and high quality care.

For Medicare, this decreasing ratio between primary care provider and beneficiary is of particular concern given the rapidly increasing number of baby boomers transitioning into Medicare.

Among the key issues addressed in the June MedPAC report is Medicare beneficiaries’ access to primary care, including the need to think about ways to incentivize medical students to choose primary care as a career choice, with particular emphasis on satisfactory geriatric care. The need for this is highlighted by the expectation that the ratio between primary care providers and beneficiaries will continue to shrink as the need for primary care providers increases with the growth of enrollment in Medicare in the coming years. Data supports this.

The ratio between practicing physician to the US population in general grew only slightly between 2011 to 2016—from 2.5 physicians to 2.6 physicians per 1000 US residents, respectively. Primary care specialists treating Medicare beneficiaries grew only from 30.9% to 31.2% between 2010 and 2017. And in 2017, <1% of all physicians who treated beneficiaries in the traditional Medicare fee-for-service program were geriatricians, about 1800.

Although current access is generally adequate, the report emphasized the need to continue ensuring access to primary care for seniors—given its critical role in creating and delivering the type of care essential to providing high quality affordable care—that is accessible and comprehensive, provides continuity as well as coordination with multiple providers and settings, and takes into account the whole person.

This type of care is particularly important given the multiple, often chronic, conditions many seniors are managing.

The report also highlighted the growing number of nonphysician primary care providers, advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), and physician assistants (PAs), to provide many of the primary care services for Medicare beneficiaries. In 2017, 212,000 nurse practitioners and PAs combined billed Medicare for services, representing a doubling of services by these nonphysician providers from 2010.

Given their important and increasing role in providing primary care services, the report focused on the need to better understand the “breadth and depth” of the services provided by these nonphysician providers and to ensure that payments to them are accurate.

As mandated, the report provides Congress with information on which to inform policymaking and legislation. The report is one of two (the other report is published yearly in March) in which an appointed 17-member commission provides recommendations to Congress on Medicare issues ranging from payments to health plans (both Medicare Advantage plans and traditional fee-for-service plans) to assessment of and access to quality of care.

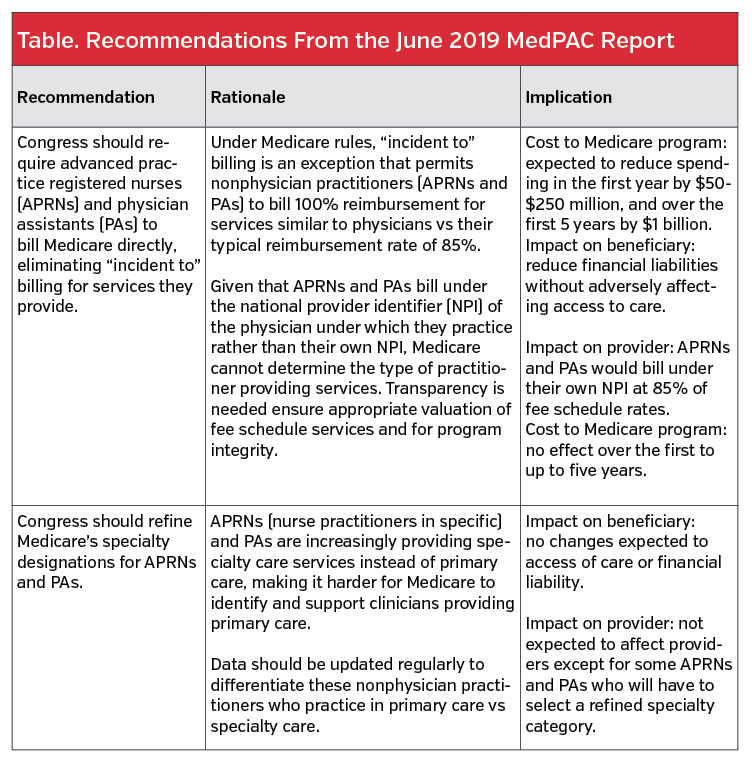

The current report offers two recommendations for Congress related to these nonphysician provider services, 1) elimination of “incident to” billing for services provided by APRNs and PAs and 2) the need to refine the specialty designation for these nonphysician providers in the Medicare program.

It also explores a way to incentivize medical students to pursue a career in primary care through loan repayment programs.

Commenting on the report, Ann Greiner, president and CEO, Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaboration (PCPCC), Washington, DC, a non-profit organization comprised of a coalition of public and private organizations focused on policy solutions to advance the mission of primary care, lauded the recommendations for increasing access to primary care services for Medicare beneficiaries but emphasized that more needs to be done.

“While many of these recommendations from MedPAC are headed in the right direction, more change will be needed to reorient the US health care system toward primary care,” she said.

Headed in the Right Direction

One step in helping improve access to and accurate reimbursement for primary care is to ensure appropriate payment for primary care providers as well as to better understand the type of services APRNs and PAs are providing. The MEDPAC report includes many recommendations to address these issues along with rationale and implications.

Ivy Baer, JD, MPH, senior director of health care affairs, Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), Washington, DC, supports refining Medicare’s specialty designation for APRNs and PAs. “The AAMC supports this recommendation, as it would provide valuable information regarding the specialties in which APRNs and PAs are working.”

Ms Greiner also sees the merit in gathering accurate information on these providers. “While it will not directly improve access, it will increase our understanding of the current state of primary care access for Medicare beneficiaries and allow for future policy changes that could increase access.”

Incentives to Increase Supply of Primary Care Physicians

Although the report did not recommend specific ways to increase the number of primary care physician providers for Medicare, it did underscore the need to design incentives for medical students and residents that specifically target those most likely to treat Medicare beneficiaries. Among the incentives discussed were those related to reducing or eliminating educational debt, such as a Medicare-specific scholarship or loan repayment program.

One way to finance the program, according to the report, would be to use the savings from the recommendation to eliminate “incident to” billing for APRNs and PAs. Substantial cost savings are expected if this recommendation is implemented (Table.)

While Ms Baer thinks loan repayment programs should be considered, she questions whether this type of program will encourage physicians to choose a specific specialty. She also stressed that debt is only one consideration of career choice. “The AAMC research has shown that debt is only a minor consideration for medical students’ choice of specialty,” she said.

Ms Greiner agreed that research shows that financial concerns are not the only reason behind the choice of specialty for medical students. “Other concerns include respect for and prestige of primary care, encouragement by professors and mentors to choose the specialty, and working conditions for primary care clinicians,” she said. “So without some effort to overhaul the way we value primary care and older adults’ health, financial support will likely not be as effective as we would hope.”

Overall, Ms Greiner emphasized the need for a broader, fundamental, systemic change to improve access to primary care physicians and pointed to a recent report by PCPCC that provides national and state level data on investments in primary care, which as a percentage of health care spending are very low.

“What is needed is rigorous measurement of where access is most limited and for whom and what we are spending on primary care as a percentage of total health care spend so that the root causes of the primary care shortage can be addressed,” she explained.

Ms Greiner also believes that managed care has a pivotal role to play. “Managed care and ACOs [accountable care organizations] hold out the promise of being able to provide the structure and financing through which population health strategies can be successfully implemented, and primary care is the foundation upon which population health strategies must be built in order to be successful,” she said. “So both types of organizations have a vested interest in the supply of primary care providers.”