Costly Burden of Managing Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic, inflammatory disease that involves an immune-mediated attack on the central nervous system (CNS), and is characterized by inflammation, demyelination, and degenerative changes.1,2 A recent study estimates that in 2017 nearly 1 million adults were living with MS in the United States.3 The disease most often appears in early adulthood, and the female to male ratio is 3:1; however, the age range for disease onset is wide with both pediatric cases and new onset in older adults.2 Four disease patterns have been identified in MS: relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), primary-progressive MS, secondary-progressive MS, and progressive-relapsing MS. The most common pattern of the disease is RRMS, affecting approximately 85% of individuals.4

Disease Burden

Common symptoms of MS vary considerably among individuals and fluctuate over time (including, but not limited to, fatigue, impaired mobility, mood and cognitive changes, pain, visual disturbances, and bladder/bowel dysfunction), resulting in a significant impact on quality of life for patients and their families.2 A study of 260 patients with MS found that depression, fatigue, family status, physical activity, and occupational status were closely associated with quality of life.5

In addition to physical and emotional impact of MS, the economic burden is considerable, ranking second among all chronic conditions in direct costs behind congestive heart failure.6 The total economic burden of MS in the United States is estimated at $2.5 billion and the lifetime costs for individual patients exceed $4 million. Because MS is a disabling condition that primarily affects younger working-age individuals, the indirect costs of lost productivity are significant. Individuals with MS have approximately four-fold higher disability and absenteeism-related costs compared with individuals without the disease.7 Additionally, high out-of-pocket costs for medications, tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), medical equipment, and inpatient and outpatient visits contribute to patient economic burden.6

Diagnosis and Treatment

The etiology of MS is unknown. Scientists believe MS is triggered by a combination of factors and research is ongoing in the areas of immunology, epidemiology, genetics, and infectious agents (eg, viruses).8 Diagnosing MS can be difficult because there are no symptoms, physical findings, and laboratory tests—alone—that can determine if the patient has the disease.9 Several strategies are used to determine if an individual meets the criteria for a diagnosis of MS, including medical history, neurologic exam, and various tests including MRI, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and blood tests to rule out other conditions.9 The 2017 revision of McDonald criteria include specific guidelines for using MRI and CSF analysis to speed the diagnostic process.10

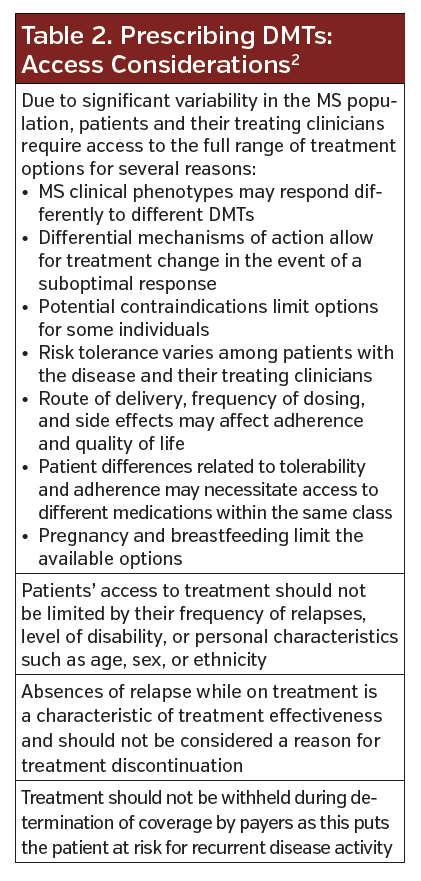

No cure exists for MS, and treating MS is a balancing act between fighting the immune response and allowing the immune system to continue to defend the body. Patients will require disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) to slow the disease progression and related disability and manage exacerbations. See Table 1 for FDA-approved DMTs. A growing body of evidence highlights the importance of early and ongoing access to treatment with DMTs.2Table 2 outlines considerations clinicians should keep in mind when prescribing DMTs.

Two new oral therapies were FDA approved earlier this year. Cladribine (Mavenclad, EMD Serono Inc) is indicated for the treatment of relapsing forms of MS, to include relapsing-remitting disease and active secondary progressive disease, in adults. Because of its safety profile, use is generally recommended for those who have had an inadequate response to, or are unable to tolerate, an alternate drug indicated for the treatment of MS.11 In the double-blind CLARITY study, patients taking cladribine 5.25 mg/kg and 3.5 mg/kg experienced a relative reduction in the annualized relapse rate (ARR) at 96 weeks compared with placebo (58% and 55%, respectively). The risk for 3-month sustained disability progression was also reduced by about 30% in both cladribine arms, with a reduction in brain atrophy as well. The most common (>20%) adverse reactions reported were upper respiratory tract infection, headache, and lymphopenia.12

Siponimod (Mayzent, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is indicated for the relapsing forms of MS, to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, in adults.11 In the phase 3 EXPAND study, siponimod reduced the risk of 3-month confirmed disability progression by 21%. It also reduced the relative reduction in the ARR by 51%. Most common adverse reactions (>10%) reported were headache, hypertension and increased liver transaminase concentration.13

Siponimod (Mayzent, Novartis Pharmaceuticals) is indicated for the relapsing forms of MS, to include clinically isolated syndrome, relapsing-remitting disease, and active secondary progressive disease, in adults.11 In the phase 3 EXPAND study, siponimod reduced the risk of 3-month confirmed disability progression by 21%. It also reduced the relative reduction in the ARR by 51%. Most common adverse reactions (>10%) reported were headache, hypertension and increased liver transaminase concentration.13

In 2018, the American Academy of Neurology published a guideline providing evidence-based recommendations for starting, switching, and stopping disease-modifying agents.14 Clinicians need to weigh the benefits against the risks when establishing a protocol to manage MS. Clinicians need to understand how DMTs affect the immune system and evaluate their safety, efficacy, and side effect profiles. Additionally, choice of therapy should be analyzed and addressed through a shared-decision-making process between the patient and clinician.

Rising Costs of DMTs

The main goal of treating patients with MS is to prevent disease progression and disability. However, health care providers are faced with the challenge of effectively managing the disease and maximizing the value of high cost DMTs. The cost of DMTs have increased dramatically over the last 10 years. Acquisition costs for nearly all DMTS exceed $70,000 annually.7

A recent study in JAMA Neurology examined the effects of DMT price growth on the Medicare Part D program. The authors estimated that from 2006 to 2016 the annual cost to the Medicare Part D program for DMTs increased from $396.6 million to $4.4 billion. The primary cost driver was the annual cost of DMT treatment, which rose from $18,600 to $75,847, or 12.8% annually. Furthermore, pharmaceutical spending per 1000 beneficiaries increased 10.2-fold (from $7794 to $79,411), and out-of-pocket patent spending per 1000 beneficiaries increased 7.2-fold (from $372 to $2673).15,16

The high cost for DMTs has negatively consequences on patients, ranging from excessive cost-sharing or deductible amounts to restrictive insurance barriers.7 An online survey of patients with MS revealed that out-of-pocket costs are the most important attribute that effects DMT treatment decisions, before efficacy, safety, and route of administration.17

A separate study that looked at impact of DMT access barriers on patients with RRMS demonstrated that issues related to DMT access occur frequently, commonly because of the need for authorizing the documentation, high out-of-pocket-costs, and agency or provider coordination problems.6

“Formulary decision makers must consider the patient experience when making DMT coverage decisions. Clinicians should be aware of how patients experience DMT access difficulties and help deliver solutions to them when feasible. The MS patient experience with DMT access will continue to evolve with ongoing policy and payer landscape changes. Hence, frequent feedback from people with MS and stakeholders will be of paramount importance to ensure access to DMTs and to measure the associated impact on outcomes,” concluded the authors. ν

References:

1. About MS. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/For-Professionals/Clinical-Care/About-MS. Accessed August 26, 2019.

2. Multiple Sclerosis Coalition. The Use of Disease-Modifying Therapies in Multiple Sclerosis: Principles and Current Evidence. A Consensus Paper by the Multiple Sclerosis Coalition. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/DMT_Consensus_MS_Coalition.pdf. Updated June 2019. Accessed August 26, 2019.

3. Wallin MT, Culpepper WJ, Campbell JD, et al; US Multiple Sclerosis Prevalence Workgroup. The prevalence of MS in the United States: A population-based estimate using health claims data. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1029-e1040. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000007035

4. Types of MS. National Multiple Sclerosis website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/Types-of-MS. Accessed August 26, 2019.

5. Schmidt S, Jöstingmeyer P. Depression, fatigue and disability are independently associated with quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: Results of a cross-sectional study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;35:262-269. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2019.07.029

6. Simacek KF, Ko JJ, Moreton D, Varga S, Johnson K, Katic BJ. The impact of disease-modifying therapy access barriers on people with multiple sclerosis. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(10):e11168. doi:10.2196/11168

7. Hartung DM. Economics and cost-effectiveness of multiple sclerosis therapies in the USA. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):1018-1026. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0566-3

8. What Causes MS. National Multiple Sclerosis Society website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/What-is-MS/What-Causes-MS. Accessed August 26, 2019.

9. Diagnosing MS. National Multiple Sclerosis website. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/Symptoms-Diagnosis/Diagnosing-MS. Accessed August 26, 2019.

10. Thompson AJ, Banwell BL, Barkhof F, et al. Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(2):162-173. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30470-2

11. National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Disease-Modifying Therapies for MS. https://www.nationalmssociety.org/NationalMSSociety/media/MSNationalFiles/Brochures/Brochure-The-MS-Disease-Modifying-Medications.pdf. Updated December 2018. Accessed August 26, 2019.

12. Chisari CG, Toscano S, D’Amico E, et al. An update on the safety of treating relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis [published online August 20, 2019]. Expert Opin Drg Saf. doi:10.1080/14740338.2019.1658741

13. Kappos L, Bar-Or A, Cree BAC, et al; EXPAND Investigators. Siponimod versus placebo in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (EXPAND): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 study.Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1263-1273. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30475-6

14. Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-778. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005347

15. San-Juan-Rodriguez A, Good CB, Heyman RA, Parekh N, Shrank WH, Hernandez. Trends in prices, market share, and spending on self-administered disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis in Medicare Part D [published online August 26, 2019]. JAMA Neurol. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2711

16. Hartung DM, Bourdette D. Addressing the rising prices of disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis[published online August 26, 2019] JAMA Neurol. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.2445

17. Hincapie AL, Penm J, Burns CF. Factors associated with patient preferences for disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):822-830. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.8.822