Congress’ Spotlight Shines on PBMs

The Senate Finance Committee recently examined the complicated role pharmacy benefit managers play in the pricing of pharmaceuticals. Six prominent themes emerged. First Report Managed Care consulted with a panel of experts to assess the impact.

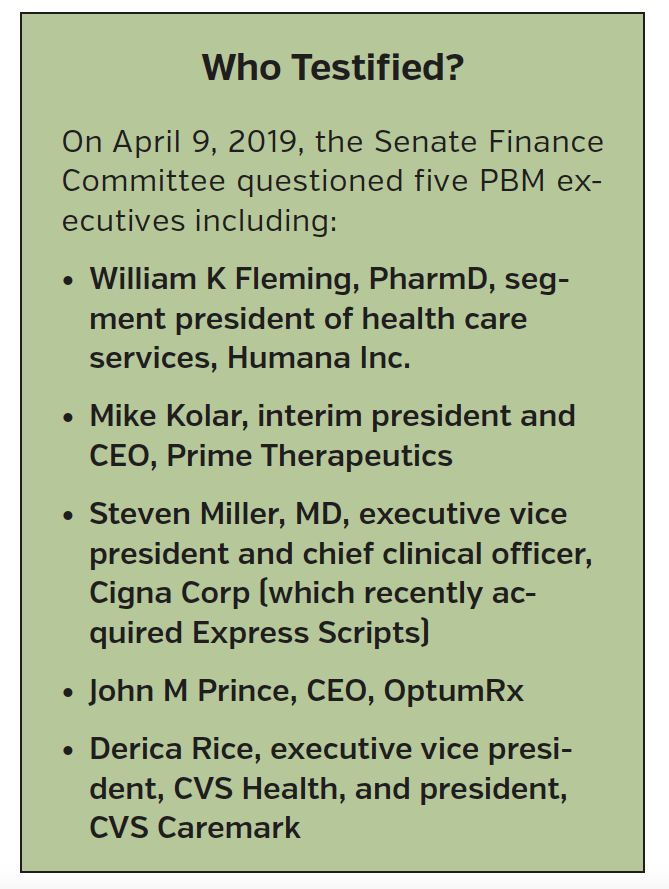

On April 9, 2019, the Senate Finance Committee held yet another hearing on prescription drug costs. Previously, seven of the top pharmaceutical executives were summoned to Capitol Hill but most recently, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) were called in front of the committee led by chairman of the finance committee, Sen Chuck Grassley (R-IA) (See “Who Testified?”). After watching the nearly 3 hours of proceedings, First Report Managed Care observed six important themes. We consulted our esteemed panel of experts to weigh in on the trends and offer their unique analysis. Our panelists included:

- Larry Hsu, MD, medical director, Hawaii Medical Service Association, Honolulu.

- Charles Karnack, PharmD, BCNSP, assistant professor of clinical pharmacy, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA

- David Marcus, director of employee benefits, National Railway Labor Conference, Washington, DC.

- Gary Owens, MD, president of Gary Owens Associates, Ocean View, DE.

- Arthur Shinn, PharmD, president, Managed Pharmacy Consultants, Lake Worth, FL

- Norm Smith, principle payer market research consultant, Philadelphia, PA

- Daniel Sontupe, associate partner and managing director, The Bloc Value Builders, New York

- F. Randy Vogenberg, PhD, RPh, principal, Institute for Integrated Healthcare, Greenville, SC

SETTING THE TONE

SETTING THE TONE

During the Hearing: In his opening remarks, Senator Grassley set the tone for the hearing by commending the intent of the PBMs and making it clear that his intent was to keep the PBM system in place. However, he wanted the committee to leave with a better understanding of how the system worked. Throughout the hearing a number of senators returned to this refrain, which resulted in the perception that PBMs may have gotten off easier than expected.

We asked our panel: Did Senator Grassley’s groundwork, along with the hearing’s outcome mean that PBMs can rest easy that their businesses are safe, though their business model might need to change?

Mr Marcus: PBMs play an integral role in the current delivery system. Thus, I think their business is safe and they should be able to work with manufacturers to develop other pricing systems that are similarly profitable.

Mr Smith: PBMs are rewarded by taking a percentage of the rebates generated by negotiating with pharma. If that’s the idea they want to hold onto, they will need to keep it opaque. However, when more than half of the costs of a drug goes toward a rebate, that system is not sustainable. They will need to change to a fee-based system with services being evaluated under real market value standards.

Dr Karnack: PBMs are probably safe since their function and business model remains unknown to most patients. The lack of transparency—along with consolidation with health insurance companies—work to their advantage for now.

Dr Shinn: That’s a good point. Many of the senators who questioned PBM executives do not have intimate knowledge of what PBMs do and how they do it. That worked to the advantage of the PBMs.

Dr Owens: Still, I don’t think PBMs or [any other stakeholders] can rest easy that their current business model is safe. PBMs are only part of the problem. On one hand, they are the middlemen who profit from high cost/high rebate drugs and other revenue streams from the pharmaceutical manufacturers. On the other hand, they have developed programs and tools that do moderate the pharmacy cost curve. I think they will have to make fundamental changes in how they do business, including increased transparency.

Mr Sontupe: I agree that no one should rest easy. As long as the PBM silos pharmaceutical cost from the overall health care value they provide, we will not be able to get this right.

Dr Hsu: There is a growing consensus that something has to be done to rein in the costs of drugs. PBMs are getting enough [negative] publicity that despite the opening remarks of Chairman Grassley, they have to propose and make some changes to their business that will decrease the costs of drugs. PBMs are too large of a target to ignore.

Dr Vogenberg: I agree. Market forces in commercial insurance, along with CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services] initiatives are already pushing change at an accelerated pace that is appropriate. It is obvious that a more holistic and integrated care management system is needed. The aforementioned mergers—including CVS Health/Aetna and Cigna/Express Scripts— illustrate that need.

THE BLAME GAME

During the Hearing: While PBMs were certainly under the microscope during the hearings, they had help playing the blame game. Referring to the Trump Administration’s recently proposed rule designed to prevent rebates paid by drug manufacturers to PBMs, Sen Sherrod Brown (D-OH) noted, “Absolutely nothing in the rule would require…pharma [companies] to lower the price of insulin or any other drug. In fact, no pharma company is willing to commit to lowering the price of their drugs if this rule goes into effect.” Sen Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) added, “I appreciate the scrutiny of the PBMs, but let’s not go away without remembering that they are [only] $23 billion out of a $480 billion problem. I stand in awe of the pharma industry’s Jiu-jitsu magic to have gotten their prime antagonists to become the focus of the problem with $457 billion remaining to be looked at.”

We asked our panel: Do you think pharma came out of the hearings looking worse than the PBMs?

Mr Marcus: Both came off looking like part of the problem rather than the solution. Pharma’s list prices are artificially high due to the rebate system—regulators have done nothing to address that. PBMs, operating within the rebate system, have recognized that higher-cost/higher-rebate drugs are the primary source of profit even if those drugs are not the best suited for a formulary.

Mr Sontupe: Pharma and PBMs come off like siblings pointing the finger at each other. It’s not a good look for either of them. Additionally, some of the PBM profits are becoming real to the general public. People are starting to understand that there is a lot more going on than a drug company setting a high price.

Dr Vogenberg: There is plenty of blame to go around for all stakeholders. Obfuscation only muddies the waters further.

Dr Owens: It is hard to say who comes off looking worse. The reality is that once consumers effectively became disconnected from drug costs in the mid-1990s, the brakes came off on drug pricing. As soon as third parties became the predominant form of payment for pharmaceuticals, manufacturers no longer had to answer to the consumer about prices and the consumer became the payer. While one would think that the large payers have leverage, they are also captive as they have to provide the benefit for medically necessary and appropriate drugs. This allows for relatively unfettered price increases.

Dr Karnack: Drug companies come out looking worse because their list pricing structures are more transparent than those of the PBMs. For example, it is easier to see how a branded drug’s inflated price gets Medicare patients into the so-called donut hole more quickly, but the public does not see the PBMs pocketing rebates.

Dr Hsu: It also does not help that big pharma is being shown in a bad light for the role it is playing in the opioid crisis. The accusations against Purdue layered on top of the rising cost of drug costs does not look good at all.

Mr Smith: The way I see it, pharma is in a better position to justify its prices. Look at the cost of developing new products in diseases with high unmet medical needs. There are a lot of risks involved. It takes courage to compete. PBMs don’t come close to incurring the risks that pharma takes on. I suspect the American public would side with pharma if it understood the full story.

Dr Shinn: It’s also important to note that pharma faces significant legal fees because they have to fight frivolous lawsuits. I used to be the medical director at a pharmaceutical company, and I would receive notice of 10 to 15 lawsuits a week. In most instances it makes sense to settle these, and that adds cost.

SHIFTING COSTS VS REAL SAVINGS?

During the Hearing: Several senators spent their time on the impending requirement that rebates go to patients at the point of sale in the pharmacy, rather than distributed to other stakeholders. It is a topic that resonates, since it enables elected officials to tell their constituents they are putting money back into patients’ pockets. But PBM executives pushed back, noting that costs will merely be shifted in the form of higher insurance payments for all, while benefiting only a few who use high-priced branded drugs. “I support the sentiment [surrounding point-of-sale rebates],” said Steven Miller, MD, executive vice president and chief clinical officer of Cigna Corporation, “but I am not sure it will be successful.”

We asked our panel: Are Dr Miller and his peers correct about that, and if so, what is needed to actually take cost out of the system?

Mr Marcus: Passing rebates to consumers does nothing to [incentivize] pharma to reduce list prices. PBMs will get less of a share of the rebates, so they will need to look elsewhere for revenue, such as higher administration fees for commercial plans or increased spread at dispensing.

Dr Shinn: Keep in mind that no one is saying that rebates are going away. They will go back to those customers that are brand utilizers and high utilizers. But the fact is that pharma is still going to be paying rebates. Money is being taken out of one pocket and put into another.

Dr Owens: Shifting the value of rebates to the consumer will only benefit those who have co-insurances in general. If a patient is on a drug that has a fixed copayment—say, $50—and the net cost of the drug is higher than the copayment, then the consumer will see no benefit at all. It may help those on high cost specialty drugs, but these patients comprise about 2% of all members. The other 98% will see minimal or no benefit. In fact, if the employer or the health plan no longer benefits from the rebates, the cost of premiums may rise for the other 98%.

Dr Karnack: Congress is probably thinking that point-of-sale rebates will work like coupons at the point of sale—but that is wishful thinking. There will be costs associated with providing the patient a rebate. As a result, drug prices may not be lower and, in fact, might increase to cover additional billing expenses.

Mr Smith: Point-of-sale rebates will be extremely difficult to implement. But politically, it could be a real winner. The key will be the decisions facing branded companies in giving up-front discounts to the list price to gain formulary access. Another open question: How to factor in a point-of-sale discount that the member sees. In work I’ve done recently, I found most pharmacy decision makers think prices will rise at the payer level.

Mr Sontupe: We tell pharma clients to stop using copay cards and provide them instead to the health plan. Allow the health plan to be the hero. In my opinion, if the chargeback system is utilized correctly, there are ways to execute the discounts at the point of sale to allow them to flow through to the patient.

Dr Vogenberg: A major overhaul is required, but that is not practical for CMS or commercial plans.

WHAT’S THE PBM VALUE PROPOSITION—AND IS IT RESONATING?

During the Hearing: PBM executives provided examples showing that their organizations are integral to keeping drug prices in check. Examples included: (1) They talked up the fact that hepatitis C medication prices have declined significantly from their original lofty and unsustainable perch. PBMs attributed the drop to their negotiating power; (2) Dr Miller noted that within the first 100 days of the Cigna/Express Scripts merger, the new combined entity rolled out a program that capped the cost

of insulin at $25 per month; and (3) They explained that their role is much more significant and meaningful than simply serving as middlemen who negotiate.

We asked our panel: Do PBMs have a legitimate point and are these successes enough to overcome the negative perception they carry?

Mr Marcus: Every PBM attempts to reduce the cost of drugs, but most efforts are limited to discrete, high-cost medications. Thus, I do not think the have enough of a tangible effect.

Mr Smith: Hepatitis C is a great example that illustrates the effectiveness of PBMs. The difference between the new drugs for this disorder was minimal. Still, PBMs can go too far, especially when one drug in a class is clearly better than the others. Consider congestive heart failure. PBMs ignored the clinical outcomes data supplied by Novartis, maker of Entresto [sacubitril/valsartan]. They made it very difficult for members to access this brand, which was a real disservice to very ill patients.

Dr Karnack: As a practicing pharmacist, it was a pleasant surprise to see hepatitis C and insulin drug prices start to decrease. But was this due to PBM effectiveness, or public outcry?

Mr Sontupe: Exactly. PBMs take the credit, but arguably the market was already headed in this direction. You could also argue that value pricing and supply and demand drove the price of hepatitis C drugs down, not PBM contracting.

Dr Vogenberg: From a pure risk perspective, PBMs have done little in recent years to make a real difference for either patients or plan sponsors.

Dr Shinn: In many ways PBMs are their own worst enemy. They haven’t sufficiently communicated the value proposition that they bring to health care. Most of the senators in the hearing probably don’t know much about the value that PBMs bring: Step therapy edits, prior authorization, medication therapy management, clinical programs. All of these initiatives keep drug costs in check, and without them prices would be even higher.

Dr Owens: The good pharmaceutical management programs that PBMs offer for their clients should be enhanced. Also, they do have leverage in many cases to negotiate lower prices. But they also benefit from higher prices and thus higher rebates and other price related revenue streams. I think this can be overcome by paying a set price for the suite of PBM services like claims payment, clinical management, and drug contract cost negotiations. Then PBM services would be like many other service industries. Employers could shop for the PBM that provides the best quality service at the lowest cost.

Mr Sontupe: I agree that the model has to change significantly. What we need is a way for pharma and PBMs to work together beyond contracting. Start with a mandate that all drug plans cover the lower of negotiated price or copay. This simple change would save patients money on most generic transactions. We hear too often that pharmacists tell patients, “If you buy the drug from us, it will cost less than your copay.” This should never happen.

OVERCOMING NEGATIVE PERCEPTIONS

During the Hearing: Despite the success stories, some senators raked PBMs over the coals. Sen Ron Wyden (D-OR) was the most vocal. “If PBMs had clear hard evidence proving that they are getting patients a better deal on prescription drugs, they’d be leafleting the countryside and shouting it from the rooftops. Instead they work overtime to keep taxpayers in the dark.”

We asked our panel: Why don’t PBMs tout their successes and show more evidence of the difference they make—vs being secretive about their processes? How do they overcome the perception that they are hiding improprieties?

Dr Shinn: PBMs seem to operate under the “less is more” adage. The less anyone knows about what they’re doing, the better off they will be because nobody really understands the PBM business.

Mr Smith: A stand alone PBM generally does not have access to patient records, so documenting their impact on total medical costs is very limited. Now that Express Scripts and CVS have merged with Cigna and Aetna, they should be able to document the benefit they provide. If it’s all driven by price, I would not expect them to offer the benefit they claim.

Dr Karnack: These mergers might allow PBMs to further pad their bottom lines via “overhead costs” that are not easily visible to the patient and public. It would be great if PBMs could pull back the curtain and publicize their drug discounts, but that will not happen.

Dr Vogenberg: In my view, PBMs have committed plenty of unethical and immoral actions over the years, but they’ve done nothing illegal per se. Toeing the line like that, and doing so in a nontransparent fashion, will enable negative perceptions to persist.

Dr Owens: As I’ve already noted, a service provider model—where the PBM functions in almost the same way as a property manager does for real estate—may be the way to eliminate inherent conflicts.

GOODBYE TO SPREAD PRICING?

During the Hearing: The senators tore into the practice of spread pricing, where PBMs charge one amount to health plans for a medication, reimburse pharmacies a lower amount, and keep the difference. Sen Bob Menendez (D-NJ) said, “It’s like asking your mom for $10 to buy a T-shirt that costs $8, getting it from the seller for only $7, and keeping the rest for yourself.” He warned the PBM executives, “Either you come to the table with real solutions to help patients…or you’ll find a legislative response you won’t care for.” Senators Grassley and Wyden have asked the US Department of Health & Human Services Inspector General to investigate the practice of spread pricing.

We asked our panel: It looks as if spread pricing’s days are numbered. Will giving up this practice—along with shifting to point-of-sale

rebates—be enough to move the spotlight’s glare off of PBMs?

Dr Shinn: The traditional PBM business model with spread pricing and rebates can't go on any further. It has to be modified.

Mr Marcus: I agree. Spread pricing is likely on its way out. It seems like an easy practice for PBMs to give up to make inroads elsewhere.

Mr Sontupe: I hope the practice is discontinued. To me, it borders on fraud. How can PBMs claim to lower the costs to the employer, yet charge the employer more than they pay? How in the world is that saving money? This should be the first thing to go, and we should be making more inroads to create value-based pricing to ensure incentives are aligned.

Dr Vogenberg: Given the separation of medications into nonspecialty and specialty categories, spread pricing will continue to come under fire while pressuring change in how contracts along the supply chain are implemented with or through PBMs. This is not just a PBM problem but a wider supply chain issue also involving the manufacturer.

Mr Smith: Transparency is not the friend of PBMs. Part of their success is that other stakeholders generally don’t know how they are getting hurt by the PBMs. “Trust, but verify,” goes the old adage. But in my experience, manufacturers did not have the capacity to verify. Most payers had other costs to worry about and didn’t realize what PBMs were doing to them.