Understanding the Complexities of MACRA

With new performance measurements set to begin on January 1, 2017, can you describe what the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is and how it will affect the way health care is delivered and paid for in the United States?

With new performance measurements set to begin on January 1, 2017, can you describe what the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is and how it will affect the way health care is delivered and paid for in the United States?

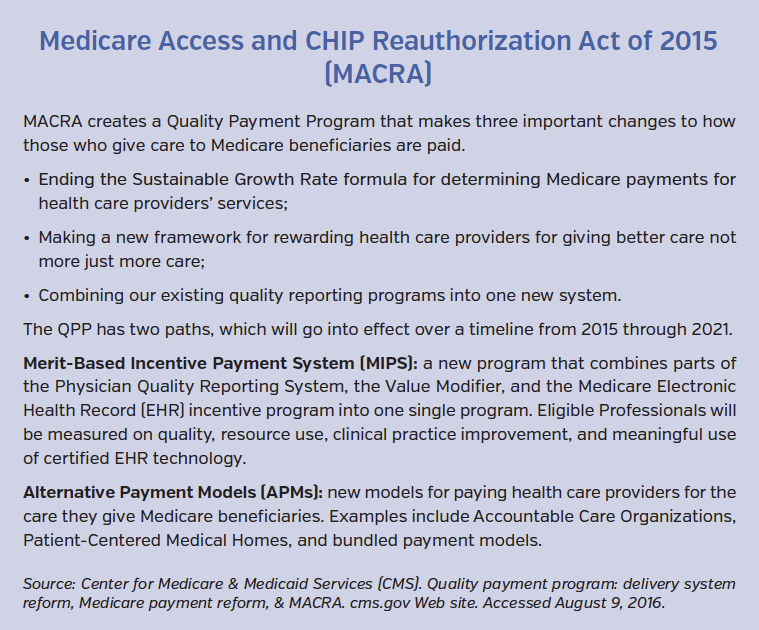

MACRA is a law that was passed in 2015 that had two major effects. First, it permanently abolished the highly unpopular Sustainable Growth Rate formula, which mandated payment cuts for physicians. In its place, it established the Quality Payment Program, which they hope will be a better approach to improving health care.

The Quality Payment Program consists of two payment pathways—the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and advanced Alternative Payment Models (APM). MIPS is essentially a pay-for-performance program that consolidates existing Medicare programs.

Advanced APMs are new mechanisms of payment that require participants to accept financial liability, typically for a population of patients.

These programs apply to Medicare fee-for-service but could easily be replicated by other payers.

What do you think are the biggest opportunities and challenges MACRA offers for patient outcomes and the improvement of the American health system?

There are many challenges to this complex law, but I think it is important to focus on how the programs affect costs. Quality is important, but it is difficult to measure. Costs, on the other hand, are easier to understand—due to the aging of the population, the Medicare program is on an unsustainable path that, if it were to continue in its current state, we would need to both cut other federal spending well below historical lows and raise taxes above historical highs to remain fiscally solvent as a nation. I think it is more likely that we will see a combination of payment cuts to providers and reductions in benefits, both of which will hurt physicians and patients.

The MACRA program, particularly APMs, place the onus on physicians and other providers to find more efficient ways to deliver care. The challenge is that we don’t really understand how to do this, and many are frustrated by the reporting requirements and perhaps don’t appreciate that simply continuing in our current state isn’t an option. To date, APMs have had some positive results, though typically lower than what many hoped for. It will be important to see how these models evolve.

MACRA does not go into full effect until January 2019, so why is it so important that practices and physicians begin preparing now? Do you have any recommendations for how practices can prepare for MACRA?

Under the proposed rule, physicians will need to begin reporting at the beginning of 2017, although many have pushed for a delay in this reporting period. The final rule is due by November 1, 2017. In the meantime, I think there are a few simple steps most physicians and practices can take.

First, determine whether they are potentially eligible for the APM pathway. There are only a handful of existing programs, and deadlines for entry have passed for most of these. Primary care practices should consider joining the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model if eligible.

For physicians and practices not in eligible accountable care organization (ACO) models, they should consider whether they may be able to join one of these models in the future. Either join an existing ACO in their area or form another one based on their connections. Medical oncologists who are participating in the Oncology Care Model may be eligible if they elect higher-risk tracks in the future. If not in one of these groups, they will probably need to wait for more options to become available and prepare for the MIPS.

With regard to the MIPS, a pragmatic suggestion given the uncertainty around the final rule and rapidly approaching first reporting year, is to become familiar with the reporting requirements for the various components and identify a minimum set of measures that the practice can report in the first year. This will minimize the risk of receiving a poor score for missing reporting requirements. If a practice wants to implement initiatives to try and perform well right out of the gate, that is great, but I suspect that ,for many measures, most physicians and practices will be indistinguishable.

Beginning in 2019, physicians will receive reimbursement through either of two payment pathways: MIPS or an APM. Can you explain how these two systems are different and what effect they will have on clinical practice?

As noted previously, MIPS is a pay-for-performance system and will adjust physician’s normal payments based on a performance score generated from four categories: quality, resource use, advancing care information (which replaces meaningful use), and clinical practice improvement activities. The immediate effect will be a need to comply with reporting requirements. It remains to be seen whether the measures and incentives can impact actual clinical practice.

APMs require participants to accept accountability through separate contract arrangements, typically involving a bonus or recoupment for meeting quality and cost targets. These are typically considered riskier, and qualification in this pathway comes with a bonus. However, both are generally oriented toward the same goals of affecting clinical practice.

Because these programs will require close monitoring of best practice, do you think that clinical pathways could be an opportunity to efficiently ensure quality care and track outcomes, especially in the oncology setting where most practices will not be eligible for an APM?

Because both programs are essentially slightly different approaches to rewarding efficient care, any delivery innovation that supports this goal should theoretically help practices succeed. Clinical pathways certainly hold promise for improving efficiency by reducing unwarranted variation.

Some have expressed concern about the ability for smaller practices to be able to sustain themselves in this new environment. Is that a sentiment you agree with? If so, what do smaller practices in particular need to start doing?

I think the jury is out on this one. It is clear that the health care industry has experienced significant horizontal and vertical integration in recent years. There is little empirical evidence to suggest this consolidation is motivated by the shift to value-based payment as opposed to the ability to wield greater leverage with payers and suppliers.

Many have argued that the reporting requirements under MACRA, inability for small practices to participate in APMs, and CMS’s projections that a higher proportion of small practices will receive negative adjustments under MIPS threaten the sustainability of small practices.

However, the reporting burden is no greater and perhaps reduced relative to existing programs in which many small practices participate. Some APMs have mechanisms which allow small practices to participate without joining a larger organization, and the projected negative adjustments are based on historical experience where small practices had little incentive to participate in these programs.

Smaller practices may be able to innovate faster than larger practices and, in some cases, have outperformed integrated systems in a few of the early models. The primary care and medical oncology medical home models are very popular among physicians because they provide support for work the practices are doing that has not been paid for.

I do think there is a need to create more opportunities for advanced APMs, particularly for small specialist practices, and CMS should continue to work with stakeholders to try and minimize the costs of reporting.

However, we should hold small practices to the same standards as large practices. In my own research looking at variation across physician practices, I’ve found that smaller practices more often fall into the extremes of efficiency or inefficiency compared to larger practices.

As far as advice, I would suggest that practices not overreact to some of the rhetoric and carefully consider their own situation. For practices with limited experience reporting quality data, professional organizations are a good source for information to get started, and after the first reporting period, this will probably be much less daunting.

Is there anything else you would like to add regarding the launch of the MACRA programs?

I would just like to reiterate that the MACRA programs, imperfect as they may be, are meant to place more responsibility on physicians to guide the future of the Medicare program and the health care system. We should put our energy into making these programs better, for if they are unsuccessful, future policymakers will likely have no choice but to revert to indiscriminate cost-control measures like the Medicare Sustainable Growth Rate, will certainly harm patients and physicians alike.