ADVERTISEMENT

A Place Patients with Cancer Can Call Home, Part 2

More than 10 years ago, John D Sprandio, MD, left his role as president of an independent practice association (IPA), frustrated by the organization’s inability to clinically integrate. Back at his practice, he found more of the same. Undaunted, he and his fellow clinicians established goals and began climbing a steep mountain toward offering consistent, high-quality care.

Along the way, Consultants in Medical Oncology and Hematology (CMOH) became the first National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)–recognized specialty patient-centered medical home (PCMH) and the first oncology medical home.

First Report Managed Care recently sat down with Dr Sprandio, who is CMOH’s chief physician. He told us how his group got started and what they did to overcome early obstacles. He also addressed the role of clinical pathways in a medical home and explained why communication is key. Finally, he provided a few practical examples that illustrate the differences between the oncology medical home model and a typical oncology medical program or practice.

FRMC: How do chemotherapy pathways impact a clinical pathway?

Chemotherapy pathways are an important component of clinical pathways. The problems with earlier chemotherapy pathway programs were restrictions regarding drug selection and the data entry requirements that resulted in significant disruptions in our work flow. It was a real physician “time-stealer.”

FRMC: How so?

Selecting and approving multiple payer-directed pathway programs within an individual practice was disruptive; typically the specific stipulations and the associated care plans were not integrated into the EMR ordering environment. Furthermore, pertinent existing patient information from the EMR environment was not integrated with pathway vendor or payer information systems.

Physicians are responsible for the consistency and quality of all of the care we deliver—beyond drug regimen selection—along the whole continuum of care. Quality and value can only be driven with a focus well beyond drug selection.

FRMC: It sounds as if standardization of process, care team responsibilities, and communication are key.

Yes, and you would think that it’s an easy thing to do, but it’s not. The problem resides in the inconsistent ways in which information is collected, presented to support and document shared decisions, and then shared with all stakeholders. This is really at the heart of the professional misery that is so common in the physician work environment today. It is one of the causes of the inconsistent execution of care, increased costs, and suboptimal quality of care.

FRMC: What’s the key to overcoming these barriers?

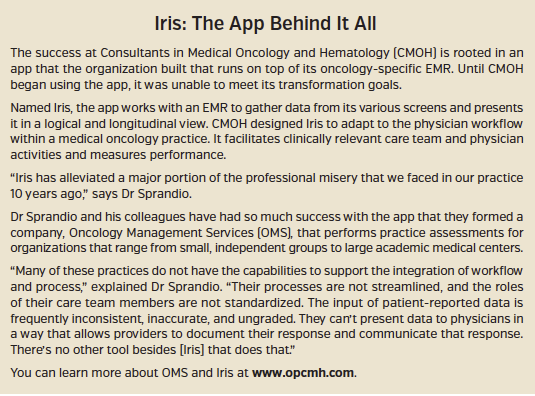

I go back to the frustration we had with our EMR. We spent a lot of money and time; yet, we couldn’t meet any of our transformation-related objectives. We had to develop an app on top of our oncology-specific EMR—that was the key.

Our app, called Iris, integrates workflow, process, data collection, and data presentation. It provides a format for documentation of shared decisions and a vehicle for efficient, timely delivery of information to all stakeholders. It also reports on key performance metrics that drive patient- and payer-desired outcomes. [Editor’s Note: See the accompanying sidebar for more on the Iris app.]

FRMC: Many organizations are fixated on hospital admissions, readmissions, ER visits, and similar quality measures. Can you talk more specifically about the key metrics the Iris app focuses on, and why these metrics were selected?

FRMC: Many organizations are fixated on hospital admissions, readmissions, ER visits, and similar quality measures. Can you talk more specifically about the key metrics the Iris app focuses on, and why these metrics were selected?

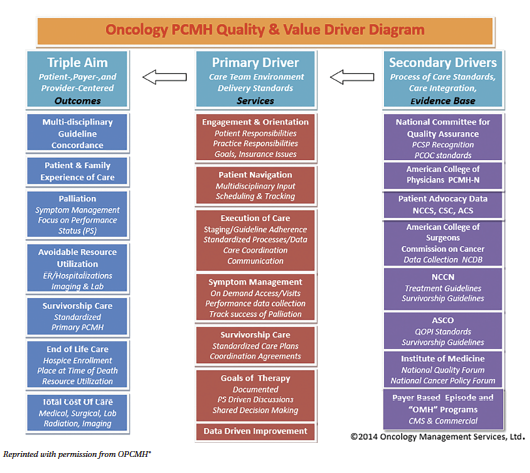

We did not initially focus on readmissions and ER visits. Reduction in ER visits and admissions were a byproduct—the end result of our efforts to fix the physician work environment. We focused primarily on the care team and the way in which we delivered services. The primary driver of quality and cost is the physician-led care team. [Editor’s Note: See the accompanying diagram for more on the OPCMH® Quality and Value Drivers.]

The more familiar secondary drivers are comprised of the evidence-based standards that are applicable to all of the activities undertaken by the physician-led care team. The primary and secondary drivers work in concert to support improvement in the desired outcomes.

So, at no time in the last 10 years did I have a meeting with our doctors to discuss the reduction of ER visits or admissions as a specific targeted goal—it is an epiphenomenon related to addressing barriers we faced in our work environment.

But, we were able to have conversations about the activities taking place within the physician-led care team. By focusing on the way care is executed, we automatically drove the reduction in ER visits and hospital admissions.

FRMC: What kinds of reductions have you seen?

Compared with 10 years ago, ER visits are down 76%, and our admission rates are down 52%. That has happened by focusing on practical things that impact physician activity and productivity, things that drive the consistency and quality of the care delivery by the care team.

FRMC: It sounds a lot like raising children, in the sense that you’re trying to change behavior without necessarily telling them what they have to do.

Physicians are overwhelmed by clinically irrelevant activity and the associated information overload. They need a structured, supportive environment to organize pertinent, consumable data so that the right thing to do is the easy thing to do. They also need accurate feedback in the form of individual performance data.

FRMC: And, just as it is with kids, there probably continue to be stumbles along the way, correct?

Well, sure, but we spot the problems more quickly. For example, at 1 of our 3 sites, ER utilization and hospital admissions increased over a 6-month period. We assessed the work flows and found out that physician productivity was affected by a family member’s health issues. We also discovered that we needed another nurse practitioner at the site. These issues had not been identified previously. But, we were able to fix the problem and lower the rate of ER visits and admissions.

FRMC: Was your ability to identify and address the problem primarily due to you having access to data?

Yes. When you have data systems and can measure and monitor performance metrics, you can address issues in a timely fashion.

FRMC: Can you provide a couple of other practical examples to give our readers a sense of how your oncology PCMH operates day to day?

FRMC: Can you provide a couple of other practical examples to give our readers a sense of how your oncology PCMH operates day to day?

A patient may walk into a primary care physician’s office with a persistent cough, and a chest x-ray shows a spiculated lung lesion that is likely to be malignant. In our model, the primary care provider calls one of our physicians. He might say: “I’ve been seeing this patient for years. He has these comorbid conditions and a probable lung. He hasn’t had a biopsy yet, but he’s very symptomatic. He has chest pain and a cough that’s keeping him up all night. Can you see him?”

Our answer in an oncology PCMH model is, “Yes!” The patient will typically be seen within 24 hours; the available data will be reviewed, the differential diagnosis and rationale for further evaluation will be discussed, all appointments will be scheduled, and the patient’s symptoms will be managed. The patient leaves the office with a diagnostic and symptom management plan—knowing that our practice is the point of first triage from that moment on.

FRMC: What other improvements to patient care can you cite other than that you are able to see the patient quickly?

In this example, our team will schedule all the pertinent diagnostic tests and specialty appointments. Just as important, we’ll track every single event that we scheduled, and patient navigators will follow up, assuring completion and retrieval of all outstanding reports.

Once a diagnosis is confirmed, we develop a multi-disciplinary treatment plan. Basically we compress the timelines to symptom management and to treatment.

FRMC: And what about for someone who comes into the ER?

It’s the same concept. Take a patient who presents in the ER with abdominal pain and for whom imaging reveals a pancreatic mass: we want that patient in our office the next day. Our goals are to relieve their symptoms and launch a diagnostic plan. Prompt expert symptom control reduces ER visits and hospital admissions.

And, once a patient is in our care, we want him or her to understand that our office is the point of first triage. Last year, 83% of symptom-related calls from our patients were managed at home via the phone.

FRMC: That’s incredible. So I take it that this process doesn’t occur in many oncology practices.

There is significant variability in many practices and programs regarding: access, acceptance of responsibility for symptom management, scheduling and tracking of tests/external appointments, communication with patients and stakeholders, and the coordination of care.

This model provides a framework for a medical home—a consistent and reliable source that can meet and coordinate all cancer care needs.