Orphan Drugs: Rare Disease Treatments Becoming Commonplace

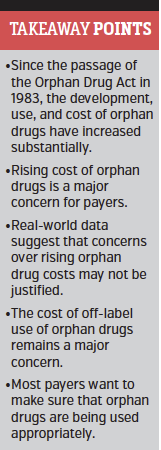

Since the passage of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, the development and use of orphan drugs has increased substantially. Given their high prices, concerns over the cost of these drugs have also increased among payers. One major concern is the increasing off-label use of these drugs to treat more common conditions instead of their designed use for rare diseases, as recently documented in a report by the American Health Insurance Plans (AHIP). Meanwhile, other experts, including Martin Makary, MD, MPH, professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins and a health care quality and safety expert, have also highlighted this trend as one that represents a misuse of the subsidies and tax breaks offered under the Orphan Drug Act to develop drugs for rare diseases, which results in inflated drug prices for off-label use and leads to higher health insurance premiums.

Since the passage of the Orphan Drug Act in 1983, the development and use of orphan drugs has increased substantially. Given their high prices, concerns over the cost of these drugs have also increased among payers. One major concern is the increasing off-label use of these drugs to treat more common conditions instead of their designed use for rare diseases, as recently documented in a report by the American Health Insurance Plans (AHIP). Meanwhile, other experts, including Martin Makary, MD, MPH, professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins and a health care quality and safety expert, have also highlighted this trend as one that represents a misuse of the subsidies and tax breaks offered under the Orphan Drug Act to develop drugs for rare diseases, which results in inflated drug prices for off-label use and leads to higher health insurance premiums.

However, a recent study on orphan drug expenditures in the United States that used real-world data to “inform discussions of payers and policy makers about access to and reimbursement for the use of orphan drugs,” found that this may not be the case.

“While payers have raised concerns about managing their drug budgets amid perceived high costs of orphan drugs and increasing numbers of orphan drug approvals, our findings suggest that these concerns might not be justified,” said Victoria Divino, senior consultant at IMS Health, Fairfax, Virginia, and lead author of the study.

Limited Impact on Expenditures

A deeper look into Ms Divino and colleagues’ study reveals data which can inform managed care providers on the current and projected costs of orphan drugs.

To estimate the economic impact of orphan drugs in the United States, Ms Divino and colleagues measured US annual spending on brand-name orphan drugs between 2007 and 2013 using the IMS Health MIDAS database of audited biopharmaceuticals.

Of the 356 brand name orphan drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) between 1983 and 2013, 316 were captured by the MIDAS database. Of these, 252 were “orphan only” drugs and 64 were “partial orphan” drugs (ie, products with both orphan and nonorphan indications).

After adjusting for partial orphan drug spending to include only spending on orphan indications, the study found that the total orphan drug expenditures represented 4.8% to 8.9% of total drug expenditures in the United States between 2007 and 2013.

Although the study found that orphan drug expenditures have increased over time, Ms Divino emphasized the importance of recognizing that the number of drug approvals has also increased. In 2013, there were 33 orphan drug approvals up from the 16 approved in 2007.

She also emphasized the need to recognize that many blockbuster orphan drugs can treat non-orphan conditions and therefore treat a larger population of patients than those with only orphan diseases.

“From a societal and equity perspective, overall spending on orphan drugs, including spending on orphan indications only, as a share of total drug spending is proportional to or potentially even lower relative to the estimated 8% to 10% of Americans affected with an orphan disease,” she said.

The study also estimated the projected spending on orphan drugs between 2014 and 2018 and found that future spending on orphan drugs will remain below 10% through 2018. “Our future analysis for 2014 to 2018 suggests a slowing in the growth of orphan drug expenditures,” she said.

Overall, the study showed that the impact of orphan drugs on payer’s drug budgets is relatively small, said Ms Divino, who also stressed the importance of recognizing the value of these drugs on many health care benefits such as contributing to a higher quality of life, reducing the burden on health care resource utilization, as well as the economic benefit of reducing disabilities and increasing productivity.

“This value far outweighs the low percentage cost of innovative medicines for orphan diseases relative to total health care costs,” she said.

GOING “OFF SCRIPT”

A major concern about the cost of orphan drugs is not about their use for rare diseases, but for their increasingly common off-label use for more common conditions, according to Mary Dorholt, PharmD, senior director & specialty clinical practice lead at Express Scripts.

“One of the major drivers of payer spending on orphan drugs is expanded indications that increase the population of patients who can now use a very high-priced medication,” she said.

Recent data from a report by AHIP highlighted just how much of the cost burden of orphan drugs comes from their off-label use for more common conditions that affect larger population of patients than the rarer conditions for which orphan drugs are developed and designed to treat. The report found that nearly half of all orphan drugs developed between 2012 and 2014 were used for nonorphan diseases and accounted for the greatest price increases of these drugs.

Of the 46 orphan drugs studied, 47% were prescribed for patients with non-orphan diseases. Over the 3-year period, the average price for the 46 orphan drugs increased by 25.9% with the largest price increases seen among orphan drugs used for nonorphan diseases, at 37%. Meanwhile, orphan drugs prescribed largely for rare diseases had the lowest price increases at 12%.

“It’s not really the true orphans we worry about,” Clare Krusing, a spokeswoman for AHIP, said in a recent Kaiser Health News report. “It’s about the other types of gaming and abusing the orphan drug act which drives up expenditures.”

The terms “gaming” and “abusing” were also words used by Dr Makary and colleagues in a commentary published in the American Journal of Clinical Oncology in which they advocated for the closure of loopholes in the Orphan Drug Act. Under the current law, companies receive subsidies and tax breaks to meet the requirements for FDA approval of an orphan drug but once approved these drugs are marketed and used off-label for more common conditions that then generate greater profit for companies.

“The practice inflates drug prices and the costs are passed on to consumers in the form of higher health insurance premiums,” Michael Daniel, a research fellow at Johns Hopkins and coauthor of the commentary, said in a press release.

Another concern about the rising costs of these drugs is the higher cost to patients, as also acknowledged by Ms Divino. “Addressing barriers to access and coverage of orphan drugs in the United States may be warranted,” she said.

Appropriate use

For Dr Dorholt, one way for payers to provide these drugs in the most cost-effective way is to ensure that patients adhere to treatment. “When it comes to orphan drugs, most payers simply want to ensure the medication is being used appropriately and that the patient is deriving the most value from the therapy,” she said.

According to Dr Dorholt, many insurers confirm that medications are used for approved purposes by implementing prior authorization programs or imposing quantity and days-supply limits. In addition, implementation of clinical programs for orphan medications can make these medications more affordable and accessible.

“Once appropriate use and supply/dose limits are achieved, the use of a specialty pharmacy with a specialized focus on individual disease states that orphan drugs impact can achieve optimal results through patient care and adherence support,” she said.

To ensure orphan drugs remain affordable for patients, Dr Dorholt recommends that plans cap the cost share for patients to $250 per prescription for a specialty medication. “This is the inflection point where we see an impact on patient adherence due to financial burden,” she said.

Overall, she emphasized the need for patients using orphan drugs to be treated by specialized care teams who are familiar with the drugs.

“These drugs typically are complex to use with a multitude of side effects,” she said. “Once the decision to dispense is made... it is crucial patients stay on their medication—inappropriate use or nonadherence really equates to waste.”